The Edith Cavell Memorial, St Martin’s Place

Discounting the temporary Cenotaph put up in Whitehall in July 1919 for the specific use as a saluting base, the statue of Cavell was the very first public memorial erected in Central London which had direct links with the First World War.

Edith Cavell, daughter of a Norfolk clergyman, was born in Swardeston near Norwich in 1865. On leaving school she worked as a governess in Brussels before deciding to pursue a nursing career and in preparation she attended the London Hospital for training. In 1906 she was asked to set up a training school for nurses in Brussels and became a matron at the Berkendael Medical Institute which became, in turn, after the war began in 1914, a Red Cross Hospital. After Belgium was overrun by the German army in August she remained at her post and, apart from giving essential medical care to them, she also assisted Allied soldiers to escape across the frontier. These actions were carried out in spite of the occupying force having given due warning of the dire consequences of punishment which would be meted out to anyone giving assistance to Allied soldiers. There is no doubt that Cavell would have been well aware of the consequences of her actions. However, in spite of this and ignoring the threat, she continued with this work until she was arrested together with several colleagues and taken into custody in early July 1915. After a short trial she was sentenced to death and, despite frantic diplomatic moves to save her life, she was executed by firing squad in Brussels in the morning of 12 October 1915 at 2 am.

The matron's death immediately sparked off a world wide sensation and caused international outrage and condemnation of the German nation's actions for an execution considered to be an act of plain murder of an innocent nurse who, after all, was only doing her duty. What was not always appreciated at the time was that the enemy was perfectly entitled to have Nurse Cavell shot if she persisted in helping soldiers to freedom. Leaving aside this argument, her execution turned out to be a very bad move on the part of the enemy and the international reaction only weakened support for Germany's cause. In addition Cavell's death also encouraged the United States government to be much less isolationist in its attitude towards events in Europe. In Britain and the rest of the Empire her death even led to a sharp increase in volunteers joining up.

In a public response to her death the Daily Telegraph immediately opened a subscription fund to provide money for a statue to the dead nurse and on 28 October and without any delay the City Council of Westminster offered an island site in St Martin's Place, north-east of Trafalgar Square opposite the National Portrait Gallery. In addition the senior sculptor, Sir George Frampton, very generously offered his services to designing a suitable memorial for free and a picture of a model of the proposed design was published in the Sphere in April 1918.

Since the 1890s Frampton had been considered in art circles to be associated with the 'New sculpture' together with Drury, Toft and Derwent Wood who between them were later to design many war memorials. In early 1916 in order to make his statue as accurate as possible he had borrowed a 'London' nurse's' cloak from the Royal London Hospital.

Although the Westminster City Council had been quick to offer this particular site at St Martin's Place it was always known that the foundations were likely to present structural problems and the contract for the necessary building work, including the preparation of the site for the statue, was awarded to the prominent construction firm of Mowlem & Co at a cost of £374.

Lord Gleichen (1) fully described the design of the memorial in the following way:

The strikingly fine marble figure of the heroine, in bold particular line, some 120 ft. high, stands in front of a tall block of granite, 25 ft. in Height. This spreads, though somewhat incomprehensibly, into the form of a sort of cross, and is surmounted by the beautiful half-figure of a woman with a child, representing Humanity protecting the Small States. (It is a pity that this is so high up that it is difficult to see properly). Below the half-figure is drapery carrying the Geneva Cross, and a scroll inscribed 'For King and Country.' At the back of the block is an angry lion in relief, symbolising the feelings of the British peoples at the outrage. On the front, below the figure, is the inscription, 'Edith Cavell, Brussels, Dawn, October 12, 1915'; and above it, on the four sides, the words Humanity, Devotion, Fortitude, and Sacrifice....'

The memorial on the south side of the 8 foot white marble statue stands on a slim pedestal against a 40 foot block of grey Cornish granite.

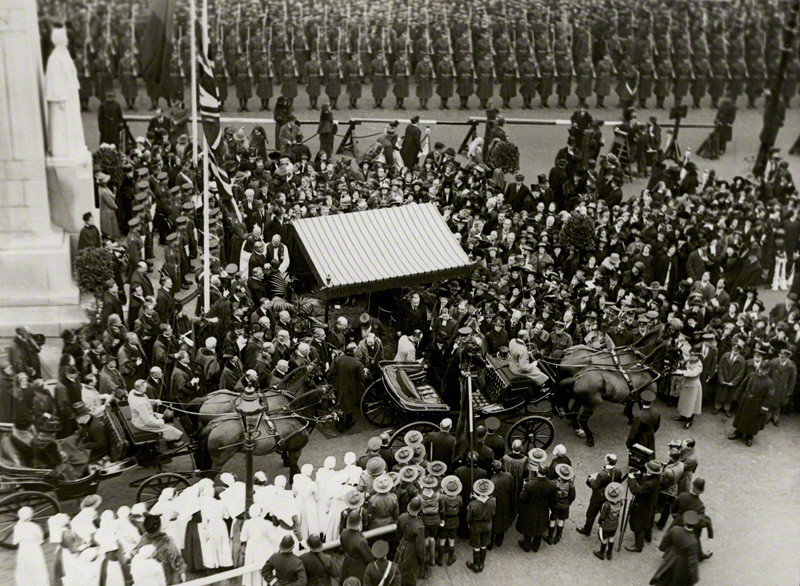

On 16 March 1920 the Lord Mayor of London was present at the site to welcome Queen Alexandra, the late King's widow, who was to unveil the memoral to the British heroine. In front of a large crowd and with many of those attending being nurses, as well as a delegation from Belgium, the statue was duly unveiled. The ceremony might have taken place much sooner but Frampton wanted to use Italian Carrara marble which wasn't available until after the war ended in 1918. He had designed the marble figure of Nurse Cavell as draped in both the Belgian flag and the Union flag and, in her unveiling speech, the Queen said of the memorial that it:

would stand for all time as a memorial of one who met a martyr's fate with calm courage and resignation which has rarely been excelled...

Two weeks later Lord Burnham, Chairman of the Cavell Memorial Committee and owner manager of the Daily Telegraph since 1916, asked the Westminster City Council if they would take over responsibility for the care and ownership of the memorial. The Council considered that, as the statue was a national memorial, the Government should be reasonable when it came to its upkeep and the Office of Works soon agreed to the request. Sadly, even as early as 1920, the steps of the memorial needed attention and the use of granite was to create cleaning difficulties over the years. In addition, in 1920, the granite front steps had to be altered, in order to provide a new landing in front of the pedestal.

The design of the memorial was met with a mixed critical reception and, perhaps, the thinking behind its design was simply too complex; by including so many 'mixed messages' the statue became immediately trapped in its own time-warp. The figure certainly manages successfully to portray Cavell's stoicism and sense of duty and the effigy in marble stone even suggests she is actually facing her executioners as she is half turned towards them preparing to meet her death. The coldness of an October dawn is also strongly suggested. Frampton, who was quite capable of designing a less buttoned up figure, sadly allowed the marble human figure and granite stone to almost merge into one. One wonders why he didn't choose to design the nurse's image in the more conventional and far less chilling bronze?

In December 1922, two years after the unveiling, The London Branch of The National Council of Women of Great Britain and Ireland requested that Nurse Cavell's 'last words' be incorporated on her memorial. Supposedly she said to her chaplain, Mr Gahan: "Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone." Frampton was happy about the change of wording but the Office of Works were not initially in favour, although they later relented. The cost of the extra wording put in place in 1924 was £13.10 shillings (£13.50).

A year before the statue was built Cavell' s body was exhumed in Brussels and later brought home to England via Dover on 15 May 1919. A memorial service held in Westminster Abbey before Cavell's coffin was taken in a large procession to Liverpool Street Station. On Platform 9 a special funeral train was ready to take her coffin back home to Norwich. After the train arrived at Thorpe Station the nurse's coffin was taken in a procession to Norwich Cathedral for her funeral. After the service she was re-buried in the precincts of Norwich Cathedral at Life's Green.

A luggage wagon had been specially adapted to bring the matron 's remains back to England and, two months later, was used again for the return of the remains of Captain Charles Fryatt who had also been executed by the Germans. The same wagon was also used for the bringing home of the Unknown Warrior in November 1920.

A great number of other statues and memorials have been put up in Cavell's memory across the world including one in Tombland in her home city of Norwich, designed by Henry Pegram, which was also unveiled by Queen Alexandra, as early as October 1918. In fact Edith Cavell was to become one of the most commemorated figures of all time especially when it came to matters of naming a new medical ward or road. Her sacrifice is unlikely ever to be forgotten and has been the subject of many books, newspaper articles, plays and films.

Sources and acknowledgements:

(1) Gleichen, E.W., London's Open-Air-Statues, Longmans, 1928.

National Archives.

- Dr Graham Keech.

- Michael Gliddon.

- The National Portrait Gallery for the 1920 photograph of the unveling ceremony by Peter Silk in 1920.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles