Haig and the destruction of a Major General

At the age of 37 in 1898 Douglas Haig was still only a Captain. He had demonstrated little intellectual distinction and, perhaps, had no need to. He had been accepted at Oxford (Brasenose - and ‘Bullingdon’) because of his prowess at polo but did not take his degree and, although he had demonstrated considerable powers of personal application at Sandhurst, he failed the examination to get into the Army Staff College (he was permitted to enter on ‘special’ grounds). Promotion beckoned at last in the Sudan War and again in the Boer War and thereafter his rise to Lieutenant General and Corps Commander by 1914 was amazingly rapid.

During the Sudan War Haig had written criticisms of Kitchener and passed them on to his patron Sir Evelyn Wood, Adjutant General to the Forces (1897-1901) and subsequently Field Marshal.

During the Boer War he had acquired a reputation for dedication to staff work - and for criticism of his superiors. A good marriage (to the Hon. Dorothy Vivian, the Queen’s Lady in Waiting) and the shrewd use of distinguished social and political connections certainly did not hinder Haig’s career advancement. Haig was appointed as Director of Military Training in 1906, Director of Staff Duties in 1907 (thus, responsible for preparing the Field Service Regulations) and GOC Aldershot in 1912. His pre-war appointments, therefore, had made him and his rigid military ideas, firmly rooted in the previous century, immensely influential. He had also developed a profound belief (clearly stated in letters to his wife) that his actions were guided by God (‘Providence’ or ‘The Divine Power’ in his own words). At the beginning of the First World War Haig seems to have emerged, fully fledged, as the individual he would remain until the end of his career: self-centred, career-minded, unwilling to reflect on his own limitations and utterly unwilling to permit any criticism, or possibility of criticism, of himself or his appointees.

Tim Travers in ‘The Killing Ground: The British Army, the Western Front & the Emergence of Modern War’ (first published in 1987 and republished in 2003 by Pen & Sword Books), among other matters, examines the increasing influence of Haig through his pre-war appointments (the focus of Chapters 4 and 5). One of Haig’s clearly stated precepts was that the leadership of the Commander-in-Chief and his Staff must not be questioned. He, and he alone, will set the strategy. (i)

Having set this principle aside while he intrigued against Field Marshal French, Haig was to enforce it rigorously and ruthlessly once he had succeeded him.

Arguably, the enforcement began in anticipation of this. Haig had become suspicious of Major General Montagu-Stuart-Wortley because he was a friend of French and because he had access to the King.

In the summer of 1907 Kaiser Wilhelm II had rented Highcliffe Castle, the residence of Lieutenant-Colonel The Hon. Edward James Montagu-Stuart-Wortley, for the season.

This had brought Montagu-Stuart-Wortley into contact with King George V. When 46th (North Midland) Division became the first Territorial division to deploy to France in March 1915 with Montagu-Stuart-Wortley as its GOC, the King took a particular interest in it and asked Montagu-Stuart-Wortley to write to him weekly. Although Montagu-Stuart-Wortley received permission from Field Marshal French and General Smith-Dorrien to do this, when the correspondence came to the notice of Lieutenant General Haking, and Haig, during the King’s tour of the front in October 1915, they expressed their annoyance. From this time Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was a marked man – particularly for Haig who wanted no questioning, nor, it seems, any possibility of any questioning, of his own views he personally expressed to the King

The catastrophe that overtook 46th Division at the Hohenzollern Redoubt on 13 October 1915 is well known and it afforded Haig the opportunity he wanted to get rid of Montagu-Stuart-Wortley.

Although it is clear from Haig’s diary entries that the Battle of Loos was being wound down after 27 September Haig was still contemplating localised attacks, three of which took place on 13th October and one of which was on the Hohenzollern Redoubt. This had been regarded by senior officers before the battle as being the most heavily defended of all the German positions. It had been captured, at huge cost (6,000 casualties) by the British on the first day of the battle, and then recaptured by the Germans on 3 October.

Montagu-Stuart-Wortley took great care in planning 46th Division’s attack on the Hohenzollern Redoubt. It is recorded in the ‘Official History’ that he wished his Division to proceed ‘by bombing attack and approaching the position trench by trench: but in this he was overruled’ (ii). Montagu-Stuart-Wortley had consulted officers involved in the previous attack on 25 September – Lt. Col. Holland of the 9th (Scottish) Division and Captain Drew of the Cameron Highlanders. He was aware that his Division was under strength and also aware of his Division’s antiquated field artillery. He therefore requested limiting the front of his Division’s attack and limiting the depth of its penetration. He also requested artillery support, having identified key targets such as the main enemy communication dugout and machine gun posts. He was also aware that perhaps his Division’s only strength was in bombing trenches since that seems to have been the main input of their training so far.

46th Division was in Haking’s XI Corps in Haig’s First Army. Haking was a Haig appointee and known for his ambition, indifferent battle planning and misplaced optimism. Haking made some concessions but insisted on a direct advance to the original proposed depth. This was a disastrous error and 46th Division lost 3,763 casualties, mostly in the first ten minutes of fighting.

The Official History of the war suggested that ‘The fighting on the 13th–14th October had not improved the general situation in any way and had brought nothing but useless slaughter of infantry.’ (iii)

It was clear that that the attack had been a disaster and Haig immediately found the scapegoat he needed. He pinned the blame on 46th Division and on Montagu-Stuart-Wortley in particular. On 24 November he wrote to Asquith that ‘.... companies of the 46th Division who had been ordered to attack .... did not go forward 40 yards.’ - a comment almost beyond comprehension bearing in mind the enormous casualty rate. Haig went on to attack the quality of territorial troops who were ’.... in want of discipline’ and that he did ‘not think much of Major General Montagu-Stuart-Wortley as a Divisional Commander ....’ (iv). It did not help that Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was not in the ‘Haig set’ associated with Haldane, the reformist War Secretary who had overseen the rise of Haig, and was regarded as one of the ‘outsiders’.

The disaster at the Hohenzollern Redoubt was also linked with Haig’s determination to get rid of Field Marshal French. Haking’s plan for the attack had been unrealistic. Haking had been proved wrong and Montagu-Stuart-Wortley had been proved right. But Haking was Haig’s protegé and supporter against French. Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was an ally of French. Haig sensed that he was very close to being offered the command of the BEF and told Asquith that 46th Division had failed despite the preparations for the attack having been highly satisfactory.

The deed was done. Haig had successfully tarnished Montagu-Stuart-Wortley’s reputation. However, since he was still well-connected he could not yet be removed from command. Instead he and his Division were to be packed off to Egypt and he was forbidden by Haig to correspond with the King.

Even the strongest of Haig’s apologists must accept that his behaviour was deeply questionable in this matter and very revealing of an unpleasant trait in his character.

It is a strange irony that in his proposals for the attack Montagu-Stuart-Wortley had actually anticipated the future successful ‘bite and hold’ tactics to be employed successfully by General Plumer’s Second Army. But in 1915 this was regarded as dangerously unorthodox.

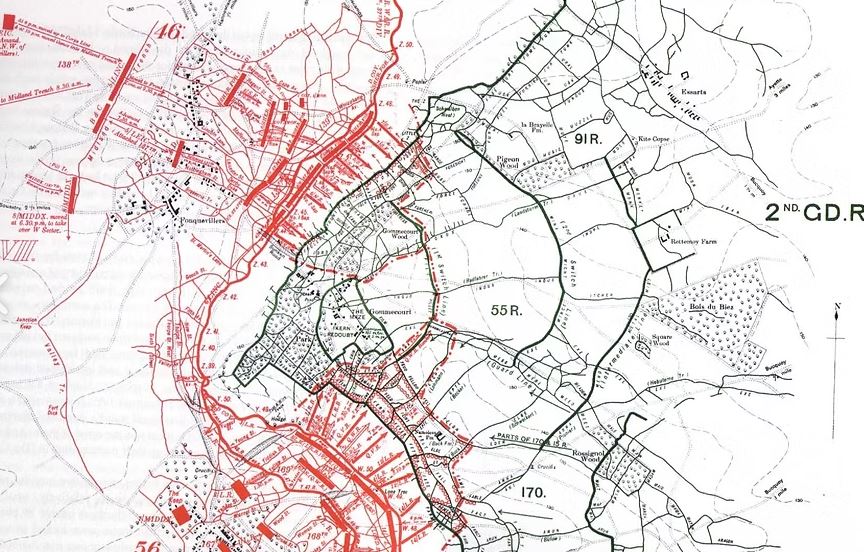

In the event only two battalions of 46th Division arrived in Egypt before it was summoned back to the Western Front where it joined the Third Army and took over trenches opposite Gommecourt.

The diversionary attack at Gommecourt on 1 July 1916 was a dreadful failure.

The initial attack by 46th Division at 7.30 A.M. failed within a half an hour, with heavy casualties from enemy fire and most of the troops having to seek cover. Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was ordered to renew the attack to support the neighbouring 56th (London) Division to the right as it came under increasing German counter attack. The 46th Division by this time, however, could provide no assistance owing to a breakdown of communication and a chaotic situation in its own shelled and waterlogged trenches. After continuous futile effort throughout the morning and early afternoon, under pressure from his superiors, Montagu-Stuart-Wortley ordered a renewed attack at 3.30 P.M. by the remnants of 137 (Staffordshire) and 139 (Sherwood Forester) Brigades as well as 1/5 Leicesters from 138 Brigade. It was clear that Brigadiers and Battalion commanders concluded there was no chance of success and, in the event, and by mistake, only one group of twenty men actually ventured into no-man’s-land and only two of those survived unscathed. One final night attack by 1/5 Lincolns from 138 Brigade was a miserable, and pointless failure.

In the evening the 56th (London) Division, was forced back out of the enemy trenches after 13 hours of continuous heavy fighting, having suffered 4,314 casualties. This sealed the failure of the operation at Gommecourt.

The 46th Division's attack had failed completely and it was noted that it had suffered the lowest casualties (2,455 killed, wounded and missing) of the 13 British Army Divisions engaged that day. It was judged responsible for the failure of the Gommecourt action in having left the 56th Division to fight on alone. 46th Division was thereafter dogged by a reputation for being a poor quality military formation - a reputation that overshadowed it until its spectacular victory in the crossing of the St. Quentin Canal in 1918.

A Court of Inquiry began on 4 July 1916 to investigate the actions of the 46th Division during the attack.

This is no place to examine the complexities of the evidence brought to the Inquiry but it seems indisputable that Haig was determined to use it as the occasion to get rid of Montagu-Stuart-Wortley. Dr Simon Peaple (v) suggests that the case against Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was far from watertight and there was a strong possibility, as the evidence was revealed and examined, that the Inquiry might exonerate him. Haig was forced to act quickly. Thus it was on 5 July, before the Court delivered its findings, that Montagu-Stuart-Wortley received the order to relinquish his command.

Dr Peaple also suggests, on the basis of the records of the Inquiry, that once Montagu-Stuart-Wortley had gone there was only a limited desire to discover the real responsibility for the Gommecourt debacle.

Haig’s vindictiveness had a clear run. Montagu-Stuart-Wortley’s old friend in high office, Kitchener, with whom he had fought at Omdurman in 1898, was dead, drowned on his way to Russia on HMS Hampshire. French, whose friendship with Montagu-Stuart-Wortley stretched back even further to the Gordon Relief Expedition of 1884-5 had been forced out by Haig.

Brigadier-General Lyons, Chief of Staff VII Corps, later described Montagu-Stuart-Wortley as ‘a worn-out man, who never visited his front line and was incapable of inspiring any enthusiasm’. It is certainly true that retirement had beckoned for Montagu-Stuart-Wortley before the start of the war. By 1916 he was 59 years old, in poor health and suffering from sciatica which must have hindered his mobility. However, this begs the question why he was not replaced before the attack. Lyons also admitted that the capture of Gommecourt had actually been unnecessary for the purpose of the diversion.

Dr John Bourne:

“Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was devastated by his replacement. ‘I could not suffer a more ignoble and heart breaking fate had I been tried by Court Martial or had I committed some egregious blunder,’ he wrote to Lord French in 1919. He spent much of the rest of his life trying, fruitlessly, to secure official rehabilitation. Posterity might find more sympathy for Montagu-Stuart-Wortley had he also tried to secure official rehabilitation for 46th Division ....” (vi)

Montagu-Stuart Wortley died 19 March 1934 at the age of 76.

References

(i) Tim Travers ‘The Killing Ground: The British Army, the Western Front & the Emergence of Modern War’ first pub. Allen & Unwin 1987 and repub. 2003 by Pen & Sword Books Page 86, 2003 Edition.

(ii) Edmonds, J. E. ‘Military Operations France and Belgium 1915: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert and Loos’ Page 384.

(iii) Ibid. Page 388.

(iv) Ed. Sheffield and Bourne ‘Douglas Haig War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918’ pub. Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2005 Pages 170-1: ‘Wednesday 24 November. Letter to Asquith’.

(v) Dr Simon Peaple ‘Mud, Blood and Determination – The History of the 46th (North Midland) Division in the Great War’ pub. Wolverhampton Military Studies, Helion & Company Limited, 2015. An excellent study of the progress of the 46th Division during the War and contains a great deal of information about Haig’s vindictiveness towards Montagu-Stuart-Wortley. Particular reference: Chapter 4, pages 91-108.

(vi) Dr John Bourne ‘Profiles of Western Front Generals, Lions led by Donkeys research project – Hon. Edward (‘Eddie’) James Montagu-Stuart-Wortley’ , Centre for War Studies, University of Birmingham, 2016

Further Reading

Martin Middlebrook ‘The First Day on the Somme – 1 July 1916’ pub. Allen Lane 1971.

John Terraine ‘Douglas Haig - The Educated Soldier’ pub. Hutchinson 1963.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles