The Story of the Iron Twelve

This is the story of eleven British soldiers, trapped behind the lines in the retreat from Mons to the Marne in the summer of 1914. It tells how they became encircled behind the German lines, how they were sheltered by French villagers and later captured and shot by the Germans.

As a piece of Western Front drama it is unsurpassed. The story has many epic elements: battles, escape, flight, solidarity, fortitude against all odds, humanity, endurance, courage, betrayal, death and tragedy. Even sex has a part to play. If it was scripted and cast in Hollywood, it would scarcely be believed. It has been described as a very remarkable story ‘about a terrible episode of the War’.(1) The executions were committed in cold blood and almost certainly after some judicial or quasi-judicial process. Today the episode remains the largest single execution of its type of British soldiers by the German Army in the Great War.

Apart from its chilling drama the story is important for other reasons. The incident underlines the courage of the soldiers concerned. They could have surrendered to the German search parties scouring the countryside for them, and done so with honour, having acquitted themselves with distinction in battle. They had no further points to prove. The relative peace of a quiet war in a prisoner of war camp beckoned. That they refused in such numbers says much about the motivation and tenacity of the ‘Old Contemptibles’. The French families who sheltered them could have asked the soldiers to move on, arguing that their presence in the midst of a French village endangered those who were looking after them; that the burden of their care should be shared with others. They did not do so.

The drama draws attention to a hitherto neglected aspect of Western Front history: the fate of those British and French soldiers cut off in the summer and autumn of 1914. One book has appeared which detailed the fate of four of them at Villeret, not far from the location of this story.(2) Some authors mention them in passing but on the whole it remains a neglected topic.(3,4)

Nevertheless it is clear from both McPhail’s account, and from the research conducted for this study, that there were considerable numbers of British and French soldiers trapped behind the lines.(5) The areas around Guise, St. Quentin, Le Cateau and Nouvion seem to have been thick with them, doubtless attracted by the presence of dense woods in which to hide. Their number is unknown, but they were a problem for the Germans. They were, for the most part, current regular army or recently recalled from the reserves, all trained and armed. Should the Allied armies ever return they had the potential to create serious problems for the Germans. The Germans had to try to capture them; their efforts used men and material that could otherwise have been used at the front. Those encircled by the Germans contributed to the Allied war effort in their own unique way.

From early 1915 the Germans became increasingly intolerant of British soldiers on the run. Those caught were at risk of being executed. The number captured and executed by the Germans is not known. Today the only evidence are the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headstones in some quiet corner of a communal cemetery carrying a date of death long after the tide of battle had passed by. One informed estimate puts the figure at ‘more than 50’.(6)

A further reason for studying this subject is that it prompts a re-evaluation of the place of women on the Western Front. To say that women are typically portrayed in much of the Western Front literature as members of a ‘back- up team’, performing a ‘support function’, either as nurses in a base hospital, or in a munitions factory, far removed from the trenches where the ‘real’ war is fought is something of an exaggeration – but it is not much of one. In this account women step out from behind the capstan-lathe, they lay aside the bedpan, and move centre-stage. It is impossible to study the experiences of escapees behind the lines without being struck by the central role taken by women. In The National Archives (TNA) at Kew there is a register of the awards given by the British government to Belgian and French citizens who helped Allied escapees.(7) It contains hundreds of names, just under half of which are female. This was as much a woman’s war as a man’s. Views of women at war based on stereotypes of the ‘roses of no-man’s land’ and the chirpy ‘canary’ working in a munitions factory have to be laid aside here. In this war the front line was behind the lines and many of the troops wore petticoats.

McPhail argues that this was because women could move about without attracting German attention, but this story shows that their sex was much more than battle-dress.(8) In essence McPhail sees female attributes as essentially negative – women succeeded because they were not men, rather than because of their own competences. Nor does the camouflage argument account for the zeal with which they carried out their mission. With their gender came the key attributes demanded by their new duties. Caring, organising, sheltering, nurturing, feeding, protecting, nursing – these qualities are feminine rather than masculine. In addition these women had those intangible personal characteristics of endurance, improvisation and sang-froid essential for the very dangerous work they were undertaking, qualities which, in another context, Tom Wolf labelled ‘the right stuff’.(9) And they had them in abundance.

This article describes the sources of information used. The soldiers at the heart of this story are named, along with what personal information is known about them. It then moves into an account of how the tragedy unfolded and its aftermath, including how the British government honoured the French families concerned. It will conclude by raising some unanswered questions about the affair and will propose possible answers to them.

Sources of Information

The existing written accounts were read and where necessary translated into English. Likely Great War Internet sites were scanned, as were the War Diaries of the two battalions most concerned. Information about the soldiers was gleaned from the CWGC database,(10) Soldiers Died in the Great War, (SDGW),(11) the War Survivors and Ward Dead file in TNA,(12) Medal Rolls, Irish genealogy websites, and the 1901 and 1911 Censuses of England and Wales. The Mayor of Iron was interviewed. The families of two of the executed soldiers were contacted: one gave access to family letters and recalled family history. Finally, several site visits were made and photographs taken of places of interest. Because of their importance the existing written accounts are first reviewed and evaluated. The other sources will be referenced as the story unfolds.

Existing Written Accounts

There are three main written sources. These are: Les Onze Anglais d’Iron.(13) This pamphlet was published locally. The author(s) are unknown (but almost certainly French). The date of publication appears to have been in the early 1920s. It is important, as the other accounts appear to use it as a source document. It seems to have been written by someone who had access to some of the surviving French participants. It does not attempt to be impartial: the Germans are vilified on every occasion, as are the French people who in any way helped to betray the soldiers. In places it contradicts itself. For this article the document was fully translated into English; this gave a fuller picture of the events and enabled some small corrections to be made to existing accounts.

Its strengths are that it gives the most detailed and entirely plausible account of what happened to the soldiers up until the moment of their arrest. It is the earliest account of the disaster and its proximity to the events it describes increases its credibility. Its weakness is that it is not obvious how the author(s) could have known what took place during the three days the soldiers were in German hands. As yet no German account of this has been traced. For this reason the version of the detention and in Les Onze Anglais appears clichéd and should perhaps be treated with caution.

The Secret of the Mill written by Herbert A Walton (14), this article appeared in a US magazine in the late 1920s. It is based on local documents and interviews with civilian survivors. Its strengths are that it provides a more detailed picture of the involved French families, their personalities, and of the post-war aftermath. It has two weaknesses. When compared with Les Onze Anglais the story it relates omits several key events and this leads it to make important mistakes. Second, like Les Onze Anglais, it is very vague about what happened to the British soldiers once they passed into German custody. The Secret is strong on character but weak on fact.

Shot by the Enemy, at the Chateau (15) written by a Branch Chairman of the Western Front Association, Derek Smith, it is a detailed and painstaking account of the tragedy. Smith is not specific about his sources, but Shot by the Enemy seems to draw on both The Secret of the Mill and Les Onze Anglais, more on the latter than on the former. It uses British military history sources to give a short account of the two British military disasters in August 1914 (Etreux and Le Grand Fayt), which form the prelude to the story. It is very strong on the history of the French families and other participants in the years after the war, drawing both on material published in a local newspaper,(16) and on an interview with M. Gruselle, the Mayor of Iron, the great-grandson of Madame Léonie Logez, the principal carer for the British soldiers. His recollections of the story as retold over the years in his family have been a vital source of information. Shot by the Enemy’s importance is not only in the detailed and comprehensive account of the tragedy, but because it raises two still unresolved questions about this affair, namely:

- Was there a twelfth British soldier who escaped the clutches of the Germans?

- Why did the soldiers stay in Iron rather than try to escape back to the UK?

The Soldiers

Details of the soldiers are given in Table 1. Unless otherwise stated all ages are at the time of death. Table 1 has been compiled from SDGW (17) and the CWGC Casualty Register.(18) These two sources yielded data for all the soldiers listed. A partial search of WO 363: War Survivors and War Dead, the ‘burnt documents’ file, (19) produced a complete attestation paper for Denis Buckley and a badly damaged fragment for Daniel Horgan. Other sources used are referenced at the foot of the table.

The fragmentary nature of the information about the soldiers makes it impossible to draw any firm conclusions. At first glance they appear to have been a typical cross-section of soldiers drawn from the 1914 Regular Army. Six were Irish, four or five were English and one was possibly born in America. These figures appear to reflect the heavy dependence of the British Army on Irish-born soldiers; this reliance had declined since the mid-nineteenth century when more than one-third of recruits were Irish(20) but they were still very important in 1914. As Holmes notes of the British Army in 1914, ‘There were Irishmen everywhere’.(21) The figures suggest that in turn Irish regiments were dependent upon English recruits. The eldest was Matthew Wilson who was 36; the average age was about 24: the youngest appears to have been Daniel Horgan who would have been 18 or 19. A 17-year-old is reported to have been in the group,(22) but no soldier of that age has been traced. Horgan was the youngest, but his stated age may be incorrect. His attestation papers are vague as to his birthday stating only that he was ‘born 1896’.

Perhaps it is possible to see in the composition of the group an element that contributed to the tragedy which was to befall them. It is obvious from Table 1 that there was nobody with any great claim to seniority based on rank, age, military decoration or service. Whatever small differences had existed may not have survived once the group was hiding from the Germans. Removed from the Army with its symbols, rituals and routines (uniform, drill, senior officers, pay, discipline) then any individual’s claim to formal status and authority based on the Army rank may well have evaporated. Lacking direction and control, and without an individual who could have taken and imposed the hard decisions that had to be made if any were to be saved, then perhaps this group was drifting towards disaster from the very start.

Formal command is only one source of authority. Perhaps one possessed the charisma to impose his personality on the group, but no trace of such a man survives. It is only at their last moment that any one of them steps out from the group and makes a personal mark, and this account cannot be verified. They truly were les onze anglais and not eleven individuals.

The Background

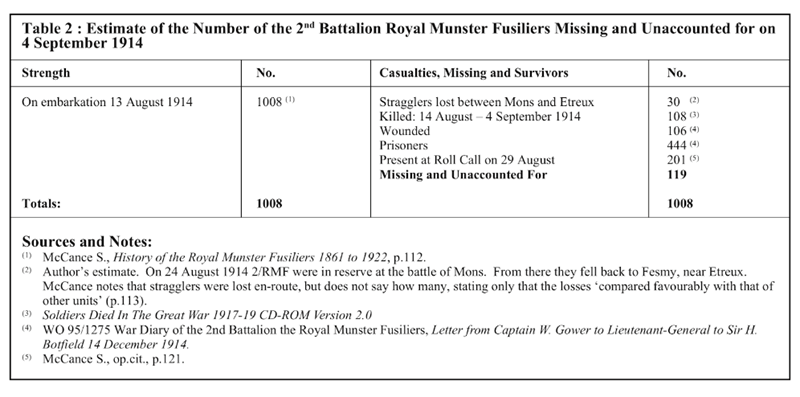

It is beyond doubt that these soldiers were stragglers from two encounters between the German and British Armies in the last week of 1914. These were at Le Grand Fayt and Etreux. Both the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers (2/RMF) and the 2nd Connaught Rangers (2/CR) were part of 1 Corps; 2/CR was part of the 2nd Division, 5 Infantry Brigade; 2/RMF were a 1 (Guards) Brigade battalion in the 1st Division. On the afternoon of 26 August 2/CR were deployed about two miles east of Landrecies; they had been detailed to act as rear-guard to the brigade’s retreat. Misinformed as to the Germans’ position, 2/CR was encircled by them in an area around Marbaix and Le Grand Fayt. They emerged with nearly 300 men missing. (23)

The next day (27 August) 2/RMF and two troops of the 15th Hussars were defending the crossings of the Sambre Canal between Catillon and Etreux, about six miles south-west of Le Grand Fayt. They were deployed along the road linking Bergues and Chapeau Rouge. They came under German attack during the morning. Orders to retire from Brigadier-General Maxse, GOC 1 (Guards) Brigade never reached them. They were left isolated as other units in the brigade on their flanks withdrew and by early evening their line of retreat across the canal to the relative safety of Guise had been severed. Surrounded by a much superior German force, they lost their CO, Major Charrier. His successor, Lieutenant Gower, surrendered at about 9.15 pm.(24) He was subsequently interned in Holland.(25)

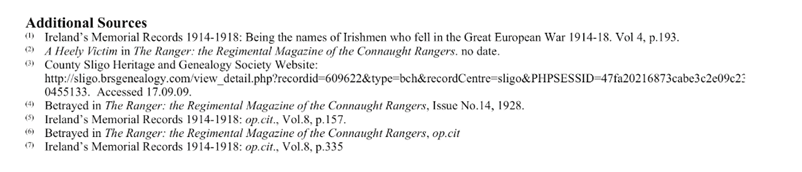

From his internment he wrote an account of the battle and of its aftermath.(26) It appears from this that the Germans had considerable difficulties in locating the missing Munsters after the battle. Whilst he was their prisoner Gower observed that the Germans were still bringing in Munsters from the battlefield up to nine days after the battle. Using the information in Gower’s letter, McCance’s regimental history(27) and SDGW it is possible to estimate the number of Munsters who escaped the action and the subsequent German round-up. This is presented in Table 2.

Assuming 30 stragglers became lost before the battle of Etreux, then there were about 120 Munsters still on the run one week after the battle. Gower’s letter can be further used to estimate the minimum numbers of 2/RMF in hiding. He knew the numbers of prisoners and wounded (he uses the word ‘exactly’ to describe the number of wounded), but he could neither have known the number of dead; bodies would be scattered over quite an extensive area, others obliterated; nor could he have known how many were on the run. Gower estimated that there were 159 Munsters killed in action during the Etreux battle. With the benefit of hindsight it can be seen that that figure is incorrect. SDGW gives the number of RMF who died between 27 August and 4 September 1914 as 108. The difference of 51 between Gower’s estimate and the more accurate count in SDGW is probably a good indication of the minimum number of Munsters who went into hiding at the end of the battle. An alternative explanation is that Gower well knew that there were numbers of 2/RMF in hiding but writing from his place of internment he chose to conceal it by inflating his estimate of the number of dead.

It can be stated with some confidence that the numbers of 2/RMF missing one week after Etreux was between about 50 and 120. Anecdotal evidence supports the idea that there were considerable numbers of Munsters trying to escape. Beaumont, another soldier trying to return to the UK, describes a night passed in Edith Cavell’s shelter in Brussels in the spring of 1915. Of the fourteen or so soldiers there that night, ten were Munsters.(28)

Estimating the number of Connaught Rangers trapped behind the lines after the disaster at Le Grand Fayt on August 26 is more difficult. What is known is that of the 300 Rangers missing, 17 were killed(29) or died between 26 August and 4 September.(30) How many of the remaining 280 or so ended as PoW, on the run, or escaped to rejoin their units is not known.

To the east, south of Wassigny, can be seen the Andigny Forest. Both of these forests provided shelter for Allied soldiers behind the lines. The Munsters held the line on the road from Bergues north to Chapeau Rouge, just off the map, and fell back to Etreux. Le Grand Fayt lies just to the north of the map; Guise just to the south. (Extract from No.59 (Sept 1917) Straßenkarte de 2 Armee. Gedruckt v.d. Zentral-stelle d. Vermessung dienste der 2.Armee. Source: Army Trench and Operations Maps from the National Archives, CD-ROM published by the Naval and Military Press: map of Arras-Valenciennes-St. Quentin area in General 2nd, 4th, 6th and 17th Army folder)

Such large numbers of missing soldiers were made possible by both natural and man-made factors. The natural factors can be found in the nature of the countryside. The area in which both of these battles took place is quite unlike the plains of Picardy, Champagne, Flanders and the Somme where the bulk of Western Front fighting took place. This is L’Avesnois, where the last vestiges of the Ardennes meet the plains of north-west France. Now, as then, it is a combination of lush, undulating, well-watered small fields, surrounded by thick hedges with few gaps, interspersed with great, dense forests such as Nouvion and Mormal. The term bocage is often used to describe the countryside and indeed the region is much more like Normandy than the Nord and Pas-de-Calais. Further, in late August the crops would have been well grown but unharvested due to the war, providing escapees with further cover.

Nature sometimes receives a helping human hand and the German Army provided this. First, there is some evidence that at least one of the eleven soldiers, William Thompson, spent some time in German custody. According to a posting on The Great War Forum(31) Thompson’s great- grand-daughter is quoted as saying that he, along with other British soldiers, was ‘taken prisoner by the Germans at a place called Bo[ué].(32) They were taken to a forest nearby but it was bombed by the British and in the woods till October the 21st’. This evidence shows that German prisoner security arrangements were possibly lacking, but as some of the eleven soldiers were armed when they were finally captured, it is likely that not all of them passed through German hands.

Second, the Germans forced many local residents into the forests around Nouvion. McPhail(33) cites a diary kept by a M. Leduc, a local headteacher, in which he describes how, on 24 August, the Germans entered Nouvion and set fire to the town as a reprisal for alleged sniping by the locals against the Germans. Whether or not there had been such attacks is not clear; possibly the Germans were fearful of a repetition of the damage inflicted by francs- tireurs, or civilian sharpshooters, on German forces during the Franco-German War of 1870- 71. The locals, and the refugees who had taken shelter with them, were forced to move into the fields and the forest. This happened three days before the battle at Etreux and two before that at Le Grand Fayt. Thus any fleeing British soldier would find camouflage in numbers. The sight of people living rough in the forests around Nouvion would not attract any special German attention, nor would anyone, given the presence of numbers of Flemish-speaking Belgian refugees, who was unable to speak French. In this sense the Germans had already prepared relatively safe havens for the British soldiers before the two battles had started.

In late August and early September the woods and fields were hiding Belgian, French and British soldiers, as well as refugees. A local woman, Aline Carpentier who was, according to McPhail an ‘assiduous observer and diarist’; noted in her diary entry of 4 November that, ‘men hid in the woods and abandoned houses torn between remaining concealed and trying to rejoin their units.’(34) On the same day her son found a group of twenty British soldiers hiding in the undergrowth. Local villagers appear to have kept soldiers in hiding supplied with food and acted as guides, scouts and lookouts for them.(35)

The German reaction to these unwanted guests was initially tolerant. Any Allied soldier could come out of hiding and surrender and expect to be treated as a PoW. The Germans began issuing a series of proclamations giving Allied soldiers a period of grace (usually one or two weeks) in which to surrender. This could indicate a growing concern on the part of the Germans about the number of Allied soldiers on the run behind their lines. Numerous pronouncements appeared stating that after a period of grace any British soldier caught in or out of uniform would be regarded as a spy and shot. Smith cites four such proclamations: 2 November 1914, 8 November 1914, 1 March 1915 and 15 October 1915.(36) McPhail states that according to German pronouncements, any Allied soldier taken after 4 December would be shot.(37) A reward of ten francs per head was offered to anyone turning in an Allied soldier on the run. This was hardly exorbitant, about the same as the average daily wage for a skilled worker in France in 1913.(38) The small amount of reward money suggests that greed would not determine whether or not informers turned in British soldiers.

German attitudes were not the only factor to change. Spending late August and September in the woods and fields, fed and guarded by villagers could have been an idyllic experience. Yet as late summer gave way to the rain and mists of a cold Aisne autumn, many soldiers felt forced to seek somewhere warmer, drier and where food was more assured. This need appears to have been a compelling one, which forced the eleven British soldiers into the arms of the villagers of Iron.

The ‘Eleven’ arrive in Iron

The first contact came on 15 October, 1914 when Vincent Chalandre came across nine British soldiers in the fields near Iron, a small village of 500 souls about three miles to the south of Etreux. The soldiers, still in possession of their rifles, were scavenging for raw carrots and other root crops.(39) They asked Chalandre for bread. Chalandre was a retired silk weaver living in Iron but he worked as a casual labourer for Monsieur and Madame Logez, smallholders who owned a mill in the same village. Touched by the plight of the nine, reduced to rooting in the fields for vegetables, Chalandre resolved to help them. Monsieur Logez had suffered a stroke and appears to have been mentally incapable; in these circumstances Madame Léonie Logez had taken over the running of the family business. As well as her husband, she had a son, Oscar, aged 16, and daughter Jeanne, aged 15, to help her.

Cometh the hour, cometh the woman. For Walton, who met Madame Logez several times as part of the research for his article he was:

greatly struck by her boundless energy even after the cruel trials that she suffered as a result of her devoted care to the British soldiers. It was a rare experience to listen to this wonderful French woman as she recalled in a most matter- of-fact way, how she responded to M. Chalandre’s request for aid: “How could I do otherwise than help these poor fellows who were lost and starving?” she asked. “It was my simple duty.” She set about the task of saving the pauvres enfants, as she continually called them, with rare resolution. (40)

Les onze Anglais describes her as a ‘dynamic woman and a good patriot’.(41) Her first response was to organise shelter for the nine soldiers in a large hut belonging to her, located in fields she owned. This was very dangerous as there were Germans billeted in the village. Despite the risks involved she organised food supplies for them, using her cover as a smallholder who owned cows. She took soup and bread hidden in a milk bucket to the hut in which they were hiding. She raised no suspicion with the resident Germans, whom she often met on her errands of mercy to the fields. This arrangement lasted for five days. On October 20 the weather deteriorated and Madame Logez decided that the nine soldiers should take a hot supper and spend nights in her mill, a little to the north of the village. By day the soldiers would return to the hut in the fields very early in the morning, returning only at nightfall. This system continued until 1 November when it was decided to split the sleeping accommodation. Five soldiers should sleep at the mill; four would go to Chalandre’s house in the village itself.

Whether they were in the hut or at the mill, Madame Logez remained responsible for feeding them. Her smallholding enabled her to move around carrying meat and cereals; her mill gave her access to flour, which she used to bake bread for the soldiers. She organised a network of women, rendezvous and pick-up points to furnish the considerable supplies demanded by the daily task of feeding the nine soldiers. In this she was helped by Vincent Chalandre’s ‘brave wife’,(42) their ‘heroic’ daughter Germaine, aged 20, (43) and a Madame Vigèle who secured them clothes, milk and food. A Mme Jules Dufour also helped; she ferried food and other supplies from the house of a woman who had died during the invasion.(44) Madame Logez, Madame Chalandre and Germaine remained responsible for taking the food to the soldiers in their hut. Madame Chalandre had four other children apart from Germaine. These were: Marthe, aged 14; Marcel, 10; Leon, 7; and Clovis, 16.(45) It was Clovis who, on 6 or 7 December discovered two more British soldiers hiding in the woods. Madame Logez accommodated them with alacrity observing only that, ‘If I can keep nine, I can keep eleven.’(46)

The first portent of doom arrived on 15 December when forty German military police arrived on motorcycles at the mill. Madame Logez, displaying considerable bravery and nerve, delayed them just long enough for her daughter, Jeanne, to warn the soldiers who were asleep in the loft to escape through the rear. They managed to get clear of the mill, crossed the river and hid in a copse on the other side. The Germans surrounded and then entered the mill. They searched it and found nothing save some flour and supplies, and no indication of the English presence. Walton states that the soldiers used this escape route ‘frequently when in danger of discovery’(47) which suggests that this was not the only occasion the soldiers had a close call. In a small, tightly-knit community, where many people were related and where most people knew a great deal about other people’s business, many must have known of the presence of the soldiers amongst them.

It is possible that the raid of 15 December was the result of information received by the Germans. On the other hand Madame Logez appeared to think that it was a ‘perquisition,’ or compulsory confiscation of food and supplies, which the Germans routinely exacted from the French communities they occupied.(48)

In the village lived a woman named Blanche Maréchal. She was married and she was generous with her sexual favours. Her lovers included German soldiers, or as Les onze Anglais puts it, ‘the Germans, too, wallowed in this filth.’(49) Another was Clovis Chalandre, the 16-year-old son of Vincent Chalandre. There was some very indiscreet pillow talk during which Clovis told her about the British soldiers. Blanche told her husband who made his own enquiries, and he stimulated gossip. One way or another the news reached one of Blanche’s other lovers, Bachelet, a 66-year-old veteran of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Clovis, who appears amply to justify Les onze Anglais’ description of him as a ‘stupid youth’, was jealous of Bachelet.(50) On the night of 21 February Clovis went to M.Maton’s brasserie where Bachelet lodged and threw stones at Bachelet’s window. Bachelet’s response shocked Clovis. Bachelet shouted, “You’ll pay for this; tomorrow I am going to inform on you and the English! - you will all be shot!” Clovia returned home - and told no one. Bachelet was to as good as his word.

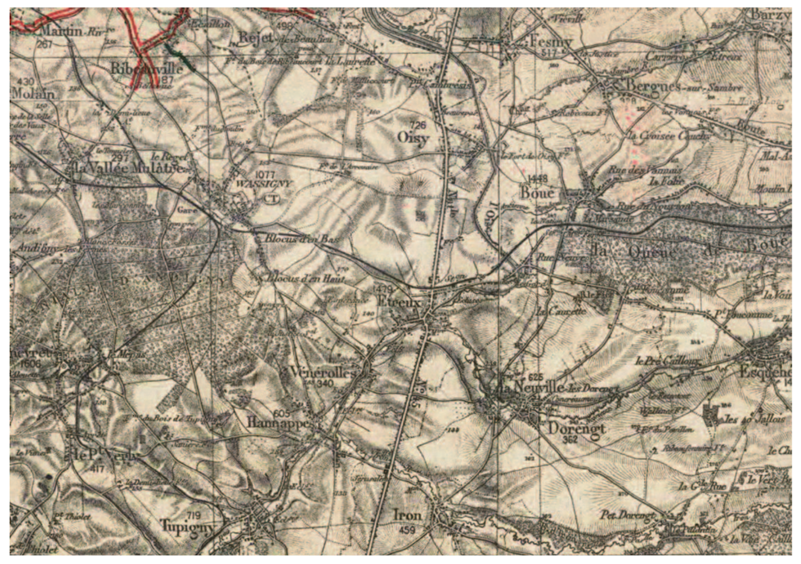

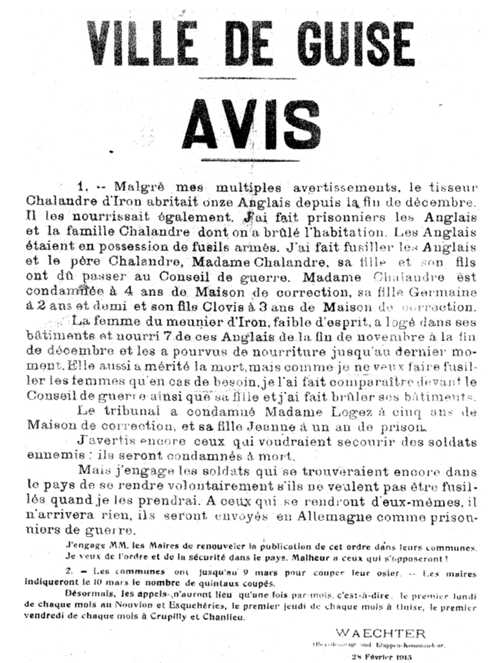

On 22 February Bachelet, driven by ‘a thirst for revenge, and a madness born of senility’(51) went to the German military headquarters in Guise. There the Rear-Zone Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Waechter and his adjutant Kolera, received him. To these two, Bachelet denounced the soldiers and those who were sheltering them. On the same morning Madame Logez, who suspected nothing, went to the same German military HQ. This was a regular visit she made to renew her trader’s pass, a permit which allowed her to move around freely. This document was usually granted to her without question, but this time she was greeted very coldly and told that she would have to stay there until the evening. The German military HQ was unusually busy. While she was waiting, though an open door she saw Waechter and Bachelet in the next room. Bachelet blanched when he saw her and he indicated that he did not wish to say any more in front of her.

Waechter began his preparations to take the British troops. All that day German troops passed up and down the road between Guise and Iron. In the afternoon Waechter and Bachelet boarded a small convoy of two cars and a lorry in La Place des Armes in Guise and set off for Chalandre’s house in Iron.

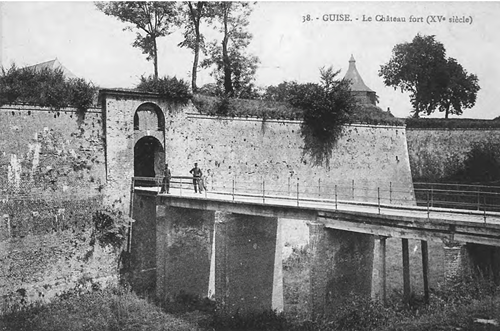

The Germans left here en-route for Iron to capture the British soldiers. On the right can be seen the pedestal of the statue of Camille Desmoulin, a Guisard and famous French revolutionary. His statue was dismantled presumably by the occupying German forces who may well have found Camille’s brand of militant French republicanism to be inappropriate. His statue has since been restored.

Behind The Lines

When Waechter left Guise he knew exactly where to find all eleven of the British soldiers – in Chalandre’s house. This was because after the perquisition raid on the Logez mill on 15 December, during which they had only narrowly escaped capture, it had been decided that the mill was too dangerous for them as the mill was a prime target for the inevitable future German raids. For this reason the seven soldiers hidden in the mill were moved to join the four in Chalandre’s house.

The arrival of the German troops was witnessed by one of the Logez ladies, probably Jeane.(52) Years later she told Walton:

‘We realised that when we saw the road suddenly covered with Boches that the crisis had come. I tried as I had done on the first occasion to warn the soldiers ... but it was impossible to do anything for they had been told where they would be likely to find the men.’(53)

On arrival at Chalandre’s house Bachelet and Waechter got out. Without hesitating, Bachelet opened the door of the house. He saw Chalandre who was in the yard and said to him,

‘I want you to know that I have sold out you and the English! ... Let that be a lesson to you for feeding deserters!’(54)

The eleven soldiers were in Chalandre’s large attic busy washing themselves and repairing their clothes or shoes. They had guns and about 1,000 rounds of ammunition between them. They could have fought the Germans, but they went quietly, perhaps reasoning that any resistance on their part would only lead to reprisals against the villagers. The Germans tied their hands behind their backs, and then bound them in pairs. Along with Chalandre, they were punched, kicked and beaten into the waiting lorries. According to Les Onze Anglais at least one was slashed on the thigh with a sabre.(55) Before they left the Germans torched the Chalandre family home and all their possessions. The villagers were forced to witness the incineration.(56)

The soldiers were then taken to the German HQ in the Guise Town Hall located then, as now, in rue Chantraine. At Madame Logez’ suggestion, a story had been agreed, in case of just such an eventuality. This said that the soldiers had been in Iron for a week; before that they were living rough and stealing their food. They knew neither the mill, nor the Logez family. It was only Chalandre who gave them food to eat, and then only for payment.

It was here that Madame Logez witnessed Bachelet’s betrayal of the British soldiers, and where they were brought after their capture and held until their execution. Since 1915 the façade has been cleaned and renovated, but its interior remains much the same. The neighbouring houses whose inhabitants were disturbed by the screams of the British soldiers can be seen on the left of the Town Hall.

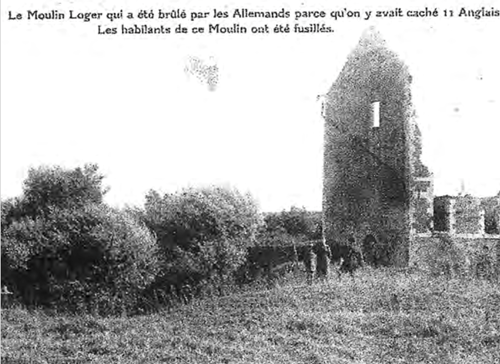

Burnt to the ground

Next day, 23 February, Mrs. Chalandre, her daughter, Marthe, and her son, Clovis, were arrested. They knew the cover story, but Clovis could not keep to it and he told the Germans everything he knew, thus sealing the fate of soldiers and civilians alike. Madame Logez was arrested on the evening of 23 February and brought to Guise Town Hall. There she was beaten up and imprisoned in the open yard for two nights, next to where the British soldiers were held. Whilst she was in detention the Germans returned to Iron and burned her mill to the ground again in front of the assembled villagers.(57) The farm’s poultry was killed on the spot by the Germans, loaded into two lorries and taken away.

At this point a curtain descends. The German record, if it exists, cannot now be traced. Les Onze Anglais claims that the twelve did not receive a trial or any form of hearing have to be regarded with scepticism; indeed, Les onze Anglais contradicts itself on this point, later quoting a newspaper report stating that the soldiers had received a trial, albeit a mock one. (58) Another source speaks of the soldiers passing before ‘a hastily convened military tribunal.’(59) It is likely that the soldiers and Chalandre were given some sort of hearing. Otherwise why wait two days? A public mass execution in Iron immediately following the arrest, with a blazing family home as a backdrop, would have been a very impressive demonstration of German power and resolve.

Observed German practice in similar cases supports the idea that the twelve were put through some type of formal hearing. For example there were three British soldiers arrested in St. Quentin at about the same time,(60) and there is the well-documented fate of the four British soldiers at Le Catelet.(61) These seven soldiers received a military trial before sentence and it is likely that the British soldiers and Chalandre went through the same process. On the other hand, Waechter issued a lengthy public statement after the execution of the soldiers, in which he makes no reference to a trial or hearing; he simply states, that ‘I had them all shot’.(62)

The Execution

According to one newspaper report, the soldiers were badly beaten up on the night of 24-25 February, to such an extent that their cries woke the residents of Rue Chantraine.(63) On the morning of 25 February the twelve were woken and subjected to ‘a terrible beating with punches, whips, cudgels; blunt instruments and rubber hammers in an orgy of joyous and strictly administered callous cruelty’.(64) Half- conscious, the twelve were put in a cart and taken into the Château at Guise by the porte-secours, a gate at the rear of the castle specially built to allow the admission of reinforcements in times of crisis.

On the other side of the relief gate a ditch had been dug. Everyone understood its significance. The soldiers were made to stand along the edge of the ditch in two batches of six. The youngest of the soldiers spoke briefly.(65) His last words were: ‘Let’s pray - chins up. Remember – Englishmen were never slaves. No-one can say that.’(66) Then the soldiers saluted. The order to fire was given twice; gunfire rang out and the Englishmen were mown down and fell into their communal grave where a German soldier gave them the coup de grace. Their bodies were then covered with soil.

At least this is the account given in Les Onze Anglais and by Walton. It is not wholly true since, on exhumation, the soldiers’ hands were tied behind their backs thus rendering the act of the final salute impossible. (67) Similarly exhumation revealed that only Chalandre of the twelve had been given the coup de grace. These errors beg the question as to how much of the rest the account of the execution is the product of a fertile imagination rather than detached and objective reporting.

Whether or not the British and Chalandre received a hearing, the members of the Logez and Chalandre family were brought before a military tribunal. Madame Logez’ life was spared. She was given five years’ imprisonment, Jeanne, her daughter, one year’s imprisonment, Oscar, her son, was sentenced to penal servitude for an unspecified period. Madame Chalandre was sentenced to four years’ forced labour; the Chalandre children Clovis and Germaine respectively drew three years and two-and-a- a-half years’ hard labour. Their sentences were served in German prisons.

Explaining the German reaction

Whether or not a trial took place, the Guise executions were calculated, deliberate and carried out in cold blood. The executions were large in terms of numbers; certainly nothing equivalent in size has been traced. They may not have been illegal, but they were harsh and this raises the question of why the Germans reacted in this way.

Occupying Germans had a choice as to how they handled captured Allied soldiers and their helpers. The death penalty was by no means automatic; discretion was possible at every level. Macintyre highlights several interesting cases, including one in which an eminent French lady hid two British troops whilst simultaneously playing hostess to several German officer lodgers. Her relationship with one of the German officers appears to have been intimate. Eventually the two British soldiers tried to escape, were captured and promptly denounced her to the Germans. One of the officers told his hostess that ‘her friends’ had been caught, but no action was taken against her.(68)

Not all soldiers caught were executed: the two soldiers in the previous incident appear to have been spared. McPhail cites a case of three who were betrayed in St. Quentin; two were shot, but the third was packed off to a PoW camp in Germany.(69) Even a death sentence did not necessarily lead to an execution. Private David Cruickshank of the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians was taken in by a family at Le Cateau and remained undetected for two years. He was captured and sentenced to death in October 1916. His protector, Madame Baudhin, was tried with him. Her son had been killed earlier in the war in the French Army. She saved Cruickshank’s life with an impassioned plea to the judges that: ‘the cruel battlefield has already robbed me of one my sons ... God has sent this British boy in his place.’ Following her plea Cruickshank’s death sentence was withdrawn and replaced with 20 years’ imprisonment.(70)

Even Waechter can be seen to have exercised some discretion. He could have shot Léonie Logez, Madame Chalandre and other members of their families. His reasons for sparing them and shooting the twelve men remain unclear, but any military governor requires at least a measure of compliance from the ruled and this may have stayed his hand in the case of the Chalandre and Logez families. He wanted the citizens of Aisne subdued with a sharp lesson; he did not want a rebellion. Why he chose to execute them all remains unclear, but this was the largest group of British soldiers taken from a single hiding place and it happened under his nose. His professional pride may well have been severely bruised.

A place in a PoW camp is offered to any Allied soldier surrendering voluntarily, but death is promised to those French people found sheltering them. Waechter is specific about what happened to the Chalandre and Logez families, but vague about the 12, other than they had been shot. His lack of detail has prompted speculation, probably incorrect, that the 12 were shot without any sort of a hearing.

It was through this gate that the British soldiers and Chalandre were led to their place of execution on 25 February 1915.

The aftermath and Bachelet’s fate

Bachelet’s treachery was not yet finished. He told his German masters all he knew concerning the whereabouts of other Allied soldiers on the run and in hiding around Iron. Consequently the Germans mounted manhunts in the area during which an unknown number of Allied soldiers ‘in hiding, who were waiting for the return of the French Army, or for a chance to escape to Holland, were hunted, taken and shot.’(71) He took his 120 francs reward for the Iron captives, but it seems to have brought him little consolation. He returned to live in Iron where he was despised, rejected and reviled by the locals. On occasion he appears to have been badly beaten up by them. He complained to the German authorities who did nothing. He was captured and taken into custody when the Allied armies returned in September 1918. He was loathed so much that his captors refused him food. He was transferred to a military prison in Châlons-sur-Marne where he died in custody whilst his case was being investigated, apparently from natural causes.(72) In another account Bachelet is reported as being found dead on arrival at the military prison.(73) Whatever the manner of his death, he maintained to the end that the men he had denounced to the Germans were not soldiers on the run, but ‘deserters who had got what they deserved’.(74)

The Logez family

Madame Logez was sent to Delitsch prison which appears to have been an important incarceration centre for French women convicted of helping British soldiers. There she was, in her own words, treated like a criminal ‘and herded with murderers, forgers and thieves. We suffered greatly from the damp, and it sends a shiver through me today to think of the food we were forced to eat. ... I was ill most of the time I was at Delitsch. It lasted more than three years and a half – a purgatory that only ended with the Armistice’.(75) Her daughter, Jeanette, went with her to the same prison. Madame Logez’ husband was forced onto the streets where he lived on neighbours’ charity until his death shortly afterwards. When Walton visited Iron in the mid to late 1920s he found that Madame Logez had re-married and was now Madame Griselin. The Griselins were trying to rebuild the mill burned by the Germans, but had had to abandon their efforts due to lack of funds.

Burned by the Germans as part of their reprisals against the Logez family, the mill was never rebuilt.

The Chalandre family

The three youngest Chalandre children, Marthe, Marcel and Leon were turned out onto the street where, according to one account, ‘they existed by begging until the armistice’.(76) Clovis served his sentence in Rheibach prison, near Bonn; his mother and sister Germaine went to Siegburg, near Cologne. Here the Chalandre women found conditions similar to those experienced by the Logez women in Delitsch. Madame Chalandre’s health deteriorated to such an extent that she was spitting blood.(77) She was released with her daughter in 1917 and returned to Iron where they were reunited with the three youngest children. The events of February 1915 and what passed subsequently had severely depleted them all. The health of all of the young Chalandre children was broken. Clovis, released after the Armistice, seems to have been unhinged by his experiences and became mentally ill. Madame Chalandre died in July 1919 and the burden of looking after the four children fell on Germaine. Marthe was spitting blood; Leon ‘was much weakened by congestion of the lungs’.(78) Smith reports that both Marcel and Marthe subsequently died. (79)

Germaine took on the role of provider for her younger siblings. She gained employment in the Paris office of a US company, the Equitable Trust Company of New York and taught herself typing and shorthand. In April 1922 she won a major competition sponsored by l’Instringeant for the most deserving Parisienne worker, after being nominated by her fellow employees. She won 40,000 francs, furniture and a car. In 1928 she married a M. Delcher. She returned to Iron after the Second World War and saw out her days there.

Edith Stent’s visit to Iron

Walton reports that Stent’s sister, Mrs. Pryke, had visited Iron and met the Logez family. Miss Stent had married Fred Pryke of Bromley, Kent and he too served in the war as a soldier in the 15th (The King’s) Hussars. According to the 1901 Census, Stent had one sister, Edith, a school teacher.(80) She was seven years older than her brother. Walton does not give a date for the visit, but the evidence suggests that it was made between 1920 and 1927. Edith took away from Iron a curious and important memento of the incident. After the events, Madame Logez had found in the ruins of the mill a handwritten list of the names and addresses of nine of the soldiers. It had been hidden under a stone. Madame Logez gave this list to Edith and it is now lost.

PoW helpers’ medals

Recognition from the British government to the Logez and Chalandre families came in September 1920. In brief, after the war two new medals, silver and bronze, were created for Belgians and French who had helped British PoWs behind the lines. The Foreign Office (FO) ran the awards system – British military intelligence identified names to British Ambassadors who made recommendations to the FO. The FO had a wider remit than PoWs in Belgium and France, notably British and non- British civilians in neutral countries throughout the world. The effect of this wider brief was to absorb the two PoW helpers’ medals into a civilian honours hierarchy of medals, Empire awards, medallions and letters of thanks. The FO made this wider range of awards available to PoW helpers: they were now eligible for a range of decorations and medals and not just the two new medals. The hierarchy of awards was as follows:

- CBE and letter of thanks

- OBE and letter of thanks

- Silver medal and letter of thanks

- MBE and letter of thanks

- The Medal of the British Empire and letter of thanks

- Bronze medal and letter of thanks

- Letter of Thanks

A full description of how this system developed can be found in the National Archives as can a full list of the awards made to PoW helpers. (81, 82) This more liberal approach was not as open- handed as it first appeared. In the relevant file there is a concern to restrict the number of British Empire awards awarded to non-British subjects and to close the lists of those eligible as quickly as possible. Certain awards were rationed. For example, there were to be only two CBE awards made available to PoW helpers and the number of bronze and silver medals was limited to about 100 and 500 respectively.

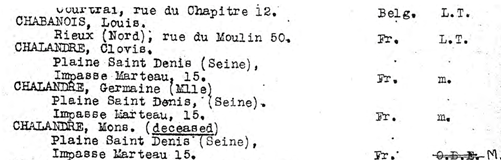

A total of five were made to the two families most concerned. Two bronze medals went to the Logez family, one each for mother and daughter. Three were awarded to the Chalandre family: a silver medal to Vincent Chalandre; a bronze medal to his wife and a bronze medal for Clovis. An extract from the list of awards made to the Chalandre family is shown here:

‘Catch 22’

There are three points concerning the awards made to the Chalandre family, which require explanation. The first concerns Clovis’ bronze medal. According to Walton and Les onze Anglais it was his lack of intelligence and weaknesses, which helped to condemn the soldiers, the Logez family, killed his own father and, indirectly, his own mother and two of his siblings. How could he be considered eligible for a PoW helpers medal? The most likely reason is that the bronze medal was a blanket award made to all helpers who had been imprisoned by the Germans, and that British military intelligence did not enquire too carefully into the circumstances of each case before passing on their findings to the relevant Ambassador

The second concerns Vincent Chalandre’s award. The scratched out OBE award indicates that he was one of only sixteen French and Belgian citizens considered for this award. He and two others seem to have been disqualified because they were dead and this award was not made posthumously. Vincent Chalandre demonstrated his courage and dedication to the Allied cause to such a level that it qualified him for one of the highest honours in the British honours system, yet he was debarred from that very award because those self-same acts resulted in his death before a German firing squad. Vincent was the victim of a ‘Catch-22’; the likes of which Joseph Heller would have been extremely proud.(83) The inability of the UK government to recognise fully his valour is a direct outcome of a decision to bestow honours which were inappropriate for what was, in effect, military type service. It is clear from the relevant file that this was due in large part to the Army Council’s reluctance to give military awards to civilians. (84)

Thirdly there is the absence of any award to Madame Chalandre. Her husband is executed, she is imprisoned, her house is burned to the ground, her children are left to fend for themselves - all as a direct result of her sheltering British Soldiers. Yet she receives nothing from the British government. Premature death for herself and three of her children is her only reward

It also appears from the British records as if Germaine Chalandre and Léonie Logez suffered an injustice in that their services to the eleven would seem to merit a silver medal rather than the bronze they received. Dame Adelaide Livingstone who worked in the British Embassy in Brussels spelled out the criteria for the award of the higher award, the silver medal. In a letter to Sir Frederick Ponsonby, one of the Palace’s eyes and ears on this part of the honours system she wrote of the gold medallion – which later became the silver medal.(85)

‘... the gold medallion [silver medal] is to be given in reward for very considerable services; indeed I am told that it is never to be given except in cases where the recipients have risked their lives by sheltering our prisoners during the German occupation in their own homes by giving them food and assistance at a time when they themselves were practically starving. (Letter written by Dame Adelaide Livingstone, Chief of War Office Special Mission to Sir Frederick Ponsonby, 14 January 1920).’ (86)

The Chalandre and Logez ladies appear to have met all the relevant criteria for the award of a silver medal. There appears to be no rational reason why they were awarded the lesser recognition of a bronze medal.

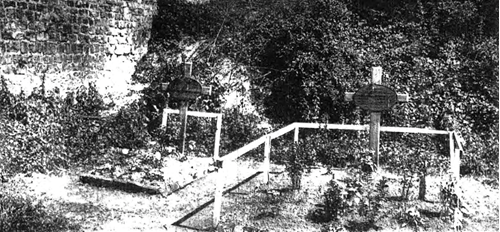

Exhumations and re-interments

The bodies of the eleven soldiers and M. Chalandre were exhumed in May 1920. The soldiers’ remains were placed in four coffins. Individual identification was not possible except in the case of M. Chalandre who was distinguished by his civilian clothes, and one of the British soldiers, thought to be Fred Innocent, who was wearing a medallion.(87) The coffins were draped in a Union Jack and interred in a collective grave in Guise Communal Cemetery under CWGC care where the soldiers are appropriately commemorated.

Chalandre was interred a few yards away. Today his grave is totally unmarked and utterly neglected. How and why the grave of a French hero, considered by the British government to be amongst the very bravest of the French and Belgian civilians to have helped Allied soldiers trapped behind the lines, has come to this pass must be a matter of serious concern. It seems likely that it is in part connected with the aftermath of the events of February 1915 which killed his wife, two of his children, and sent a third mad. They swept away his family and with them went those who most likely to ensure that his memory was preserved.(88)

Unanswered questions

Smith’s account of events in Shot by the Enemy ends with two unanswered questions. These are:

- Was there a twelfth British soldier who escaped the clutches of the Germans?

- Why did the soldiers stay in Iron rather than try to escape back to the UK?

The story of a possible ‘twelfth British soldier’ is recounted in Harry Beaumont’s account of how he escaped from German-occupied Belgium back to England.(89) Beaumont met another fugitive whilst they were both sheltering in Edith Cavell’s clinic. The second soldier was called Michael Carey, a Munster Fusilier. The story Carey told Beaumont was that Carey had been one of a party of twelve Munsters sheltered by a miller at ‘Hiron’. There they had worked for him in return for his kindness until dawn one morning when the Germans had raided the mill. The British soldiers and the miller had been tried on the spot and shot within an hour. The mill had been burned to the ground and the miller’s wife and family had been transported to Germany. Carey had been spared this fate because of a sudden inclination to leave his bed and visit friends on a neighbouring farm. There he stayed the night, returning to the mill next morning to find only the remains of a smoking ruin, and to learn of the unhappy fate that had overtaken his former comrades and benefactor.

This is clearly the same incident and Smith argues that while there are many inconsistencies there is some support for it in the form of one of the older residents of Iron who said that as a young man he had heard of an escapee.(90) Yet when Carey’s account is compared with other accounts it receives hardly any verification. The soldiers belonged to three regiments and not one; they were taken by the Germans in the afternoon and not at dawn; at the time of their capture they were sheltering in Chalandre’s house and not at the mill; it was Chalandre’s house and not the mill that was the first to be burned; the twelve were not tried and executed on the spot; and the miller (Monsieur Logez) was never implicated in the affair.

There are other unsatisfactory aspects. His name does not feature on surviving accounts of the list taken away from Iron by Edith Stent. The ease with which Carey suggests that he could come and go from his hiding place does not ring true. To clarify matters for this research M. Gruselle was asked if he had heard of another escapee in the village. He said that as a young man he had heard of one. He was then asked if a twelfth man had ever been discussed in his family. His reply was emphatic: ‘Non, c’était toujours les onze’ – ‘no, it was always the eleven.’

If there had been a twelfth man then the Logez family would have known about him. There would have been good reason to be silent about him during the war but that would have vanished with the Armistice. Then there would have been many reasons to talk about him and to celebrate his survival. His escape would provide a ray of light in an otherwise bleak picture. The fact that he was never discussed in the Logez family is conclusive proof that there was no twelfth man. Carey knew a garbled version of the incident. He may even have been hidden in Iron, but at no time was he part of the group.

There is a warning in Carey’s story for all students of the Western Front: because a personal account is vivid, exciting and recounted with conviction, this does not mean it is true. There is a whole genre of very persuasive Western Front literature based on little other than the personal testimonies of survivors of the sort given by Carey to Beaumont. Carey’s account reminds us that the test of these stories is not interest, drama, emotion or danger, but whether or not the account can be verified.

Why did the Soldiers stay in Iron?

M.Gruselle was asked if he could shed any light on the soldiers’ motivation for staying in Iron. He said that as a young man he had known older villagers who had met the soldiers and discussed the soldiers’ plans with them. According to these sources the soldiers decided to stay where they were and await the return of the Allied armies. With the benefit of hindsight it can be seen that that view was untenable, but in the winter of 1914-15 it had some foundation. Iron is roughly halfway between Ypres and the Marne. The soldiers would have been able to hear the guns of the armies as they fought down to the gates of Paris; and then again as they pounded their way back to the North Sea coast. Whilst there was gunfire there was hope. The battles of 1915 such as Neuve Chapelle, Aubers Ridge and Loos, which would show the rigidity of the Front, lay some months ahead. Then there was the general expectation that this was a war which would be over by Christmas. There were many external reasons why staying put made sense.

On the other hand, there seem to have been few internal forces to move. The soldiers had all experienced life in the chill outdoors of the forests and fields. It is now impossible to understand the social dynamics of the group, but there does not appear to have been any the eleven who had either the formal authority or the charisma to impose any alternatives on the group.

Successful escapes did take place, but mainly in the early months of the war. Les onze Anglais reports the escape of thirty-five Englishmen from northern France to Holland, organised by ‘an admirable woman, Mademoiselle Louise Thuliez’.(91, 92) Lyn Macdonald reports two similar mass escapes, admittedly in the immediate aftermath of battle.(93) Once the Front settled down the Germans tightened their grip on the rear-zone and escape became increasingly difficult throughout 1915-16. In 1915 escape networks in Lille and Brussels were broken by German intelligence, and their organisers executed, notably Philippe Baucq, Edith Cavell and Eugène Jaquet. (94) In early 1917 the German army withdrew to the Hindenburg Line, only a few miles from Iron. When that happened the front line moved to the back door and the German control tightened considerably making escape all but impossible. McIntyre reports two attempted escapes at about this time from Villeret involving three British soldiers.(95) Both failed. In truth the chances of a successful escape for the eleven became increasingly faint from the end of 1914 onwards. From that point the only alternative to hiding was surrender.

Conclusions

One conclusion relates to the precarious nature of ventures such as the one described here. On the whole communities like Iron held firm in the face of German threats: they erected a wall of silence behind which Allied soldiers could shelter. Yet the lesson from Iron was that ‘on the whole’ was not good enough. It only took one person to inform for the soldiers to be handed over to the Germans. The motive was not usually money. Lust, jealousy, anger or mental instability seem to have been much more important. By nature these are both unpredictable and volatile and they made ventures to conceal Allied soldiers a hostage to a fickle, but ultimately malign, fortune.

Episodes such as this force a re-appraisal of what the ‘Western Front’ means. It was not defined by the front line – what happened behind the lines was important. Whilst it has always been recognised that behind the lines was important in the sense of logistics, engineering and communications supporting the troops in the trenches, this case suggests that what was happening behind enemy lines was significant. The players were different and the occupying power certainly had very different concerns. This aspect of the Western Front has been neglected. For example there is no memorial for those who would not surrender. Nor is there one to the civilians who helped them. As this story shows they paid for their courage with their lives. In broadening the scope of the Western Front new actors emerge. Women take on a new role; children too young to serve in the trenches have parts in this drama. This is a positive development. This article was written in the months after the death of the last soldiers to serve on the Front; and many of us who knew them are no longer in the first flush of middle-age. Memory of the Western Front is at a critical juncture. It stands a much better chance of surviving if it encompasses a wider cast and broadens its geographic scope. It can do both by more fully embracing stories such as this one.

Hedley Malloch is a member of the WFA. He lives and works in Lille, France.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the help given by the following: Paul Crowther and Karine Sbihi for help with translations; Paul Byrne for sharing his materials and his interest; André Gruselle, the Mayor of Iron; the staff at St. Ménard Cemetery, Guise; the staff at the National Archives, Kew; Roslalind Guillemin at Guise Château; David and Janet Arrowsmith and the family of Fred Innocent; and to my wife, Fiona, for proof-reading and an inexhaustible supply of ironic metaphors and witty similes of how some men define women’s wartime roles. Last - but by no means least - to Derek Smith and the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association who kept this incredible story alive. Of course the author alone is responsible for all errors of fact and interpretation.

This article first appeared, in two parts, in Stand To! 87 and 88, in early 2010. Stand To! is one of several magazines available for free to members of The WFA. If you want to see more articles like this one, you may wish to become a member of The Western Front Association.

References:

- Walton, Herbert A, The Secret of the Mill in The Wide World Magazine c.1928 p.414.

- Macintyre, Ben, A Foreign Field (Harper Collins, 2001)

- McPhails, Helen, The Long Silence: Civilian Life under the German Occupation in Northern France ( I B Tauris, 1999)

- Macdonald, Lyn, 1914 (Michael Joseph, 1987)

- McPhail, op.cit.

- Reed, Paul: Irish Soldiers Executed 1914-1918. invisionzone.com/forums, 2005 [cited 23 October 2006]

- TNA WO 329/2957: Prisoner of War Helpers Medal

- McPhail, op.cit. P.137

- Wolfe, Tom, The Right Stuff (Vintage, 2005)

- CWGC Casualty Details [Cited 26 January 2009]

- Soldiers Died in the Great War (SDGW) CD-Rom Version 2.0 Naval and Military Press.

- TNA WO 363. War Survivors and War Dead.

- Les Onze Anglais d’Iron published by R Minon, Guise, no date

- Walton, op.cit.

- Smith, D, Shot by the Enemy, at the Chateau. Gun Fire (Journal of the Yorkshire and Humberside Branch of The Western Front Association). C. 1997 (44)

- A Notebook of a Guisard, in L’Aisne, 22 April, 1922.

- SDGC, op.cit

- CWGC op.cit

- TNA WO 363, op.cit.

- Skelley, A R, The Victorian Army at Home: The Recruitment and Terms and Conditions of the British Regular 1859-1899 (Croom Helm, 1977), p.298

- Holmes, R, Riding the Retreat: Mons to Marne - 1914 Revisited (Pimlico, 2007). P.32

- Smith, op.cit.p.37

- Edmonds, J E Military Operations: France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August-October 1914. History of the Great War (MacMilan, 1937), pp202-3.

- Edmonds, ibid, pp225-6.

- Cox 7 Co (Compliers), List of British Officers taken prisoners in the various theatres of war between August 1914 and November 1918. No date.

- TNA WO 95/1275 Letter from Captain W Gower to Lieutenant General Sir H Botfield, 14 December 1914.

- McCance, C S History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers: Volume 11 From 1861 to 1922 (Disbandment) Naval and Military Press. No date.

- Beaumont, H. Old Contemptible (Hutchinson, 1967). P.147

- Today nine British soldiers are buried in Le Grand Fayt Communal Cemetery in a common grave with three German soldiers under a headstone erected by the German Army. Of the nine, six are either named or unnamed 2/Cr; the remaining three unknowns are almost certainly Rangers’ casualties of 26 August 1914.

- SDGW, op.cit

- War Graves, 10 Executed British Soldiers. 2005 [Cited 23 October 2006].

- Boué is a village about two miles east of Etreux - see Map 1.

- McPhail op.cit. p20

- Loc cit

- McPhail op.cit. p29-31

- Smith, op.cit. p.44

- McPhail, op.cit. p35

- Ibid, p36

- Walton, op.cit. P415

- Loc cit

- Les onze Anglais d’Iron. Op.cit. p1

- Walton, op,cit p415

- Ibid, p417

- Les onze Anglais d’Iron. Op.cit. p2

- Smith, op.cit p43

- Walton, op.cit. p417

- Loc cit

- Walton, op.cit, pp417-18

- Les onze Anglais d’Iron. Op.cit. p2

- Ibid. p3

- Loc.cit

- Walton attributes this statement to Léonie Logez, but at the time of the raid she was being held in the Town Hall at Guise. M. Gruselle confirmed that in his family’s oral history Léonie remained in Guise all day. Walton has confused his femmes Logez. The most likely source of this quotation is her daughter, Jeanette. It was she who warned the soldiers on the occasion of the first raid on 15 December; the quotation which follows refers to that event.

- Walton, op.cit., pp.417-8.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.3.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.4.

- Walton, op.cit., p.418.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., pp.4-5

- Ibid., p.8.

- Entry for 25 February 1915 in a diary of an anonymous ‘local man’; held in Guise Town Archives.

- McPhail, op.cit., p.28.

- Macintyre, op.cit.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.6.

- Ibid., p.8.

- Ibid., p.5.

- Walton, op.cit., p.419.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.5

- Ibid, p.8.

- Macintyre, op.cit., p.125.

- McPhail, op.cit., p.28.

- South Lanarkshire Council Museums

Service. Soldier of the Month. [cited 2009 28 September]; Available from: http:// www.cameronians.org/museum/soldier-of- the-month_Cruickshank_print.htmj. - Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.7.

- Loc. cit.

- A Notebook of a Guisard, op.cit.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.7.

- Walton, op.cit., p.420.

- A Notebook of a Guisard, op.cit.

- Loc. cit.

- Loc. cit.

- Smith, op.cit., p.40.

- The National Archives (TNA), 1901 Census for England and Wales.

- TNA WO 32/5771: Mark of Appreciation to Allied Subjects who have helped British Prisoners of War. 1920.

- TNA WO 329/2957: op.cit.

- Heller, J: Catch-22 (Simon Schuster, 1961).

- TNA WO 32/5771, op.cit.

- How the ‘gold medallion’ was transformed into a ‘silver medal’ is a fascinating story in its own right, but it lies well outside the scope of this article. See WO 32/5571 for further details of this and other Baroque workings of the British honours system.

- TNA WO 32/5771, op.cit.

- Another source says that identification was possible in the case of four soldiers as well as Chalandre. See Entry for 25 February 1915 in a diary of an anonymous ‘local man’; held in Guise Town Archives.

- Following representations made to Le Souvenir Français, Morts Pour La France and the township of Guise, it has since been decided that the township will mark Chalandre’s grave with a simple iron cross.

- Beaumont, op.cit., pp.149-151.

- Smith, op.cit., p.83.

- Les onze Anglais d'Iron, op.cit., p.2.

- Louise Thuliez was part of Edith Cavell’s escape network and was condemned to death with her in October 1915. Her sentence was later commuted to hard labour for life.

- Macdonald, Lyn, op.cit., p.187.

- As with Chalandre, Phillipe Baucq was denied an OBE by a German firing-squad.

- Macintyre, op.cit., pp.164-5.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

This magazine provides updates on WW1 related news, WFA activities and events.

Access online tours of significant WWI sites, providing immense learning experience.

Listen to over 300 episodes of the "Mentioned in Dispatches" podcast.

Other Articles