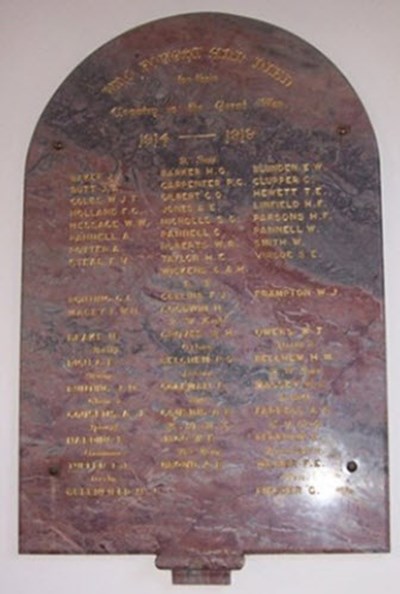

The Three Pannell Brothers: 'The Day Sussex Died'

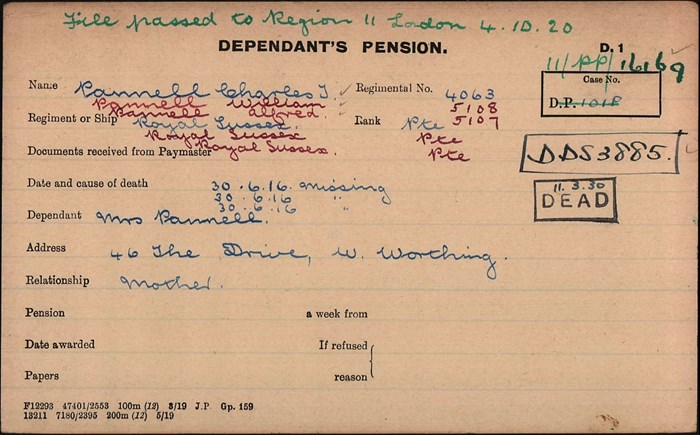

The story of the five Souls brothers, who were all killed during the First World War, is very well-known and, earlier, we published the similar story of the five Baldock-Apps brothers from Hurst Green. In looking through The Western Front Association pension records as part of Project Alias and Project Hometown , we came across the noteworthy case of three brothers who were all killed in the same battle on the same day. We believe that this is probably a unique occurrence and therefore produced the following account of this tragic story.

Charles Pannell, an agricultural labourer, married Sarah Mitchell in 1876. They lived in Lodsworth, a small village in West Sussex. They had four sons: Charles, born in 1877; George born in 1880; William, born in 1883; and Alfred, born in 1887.

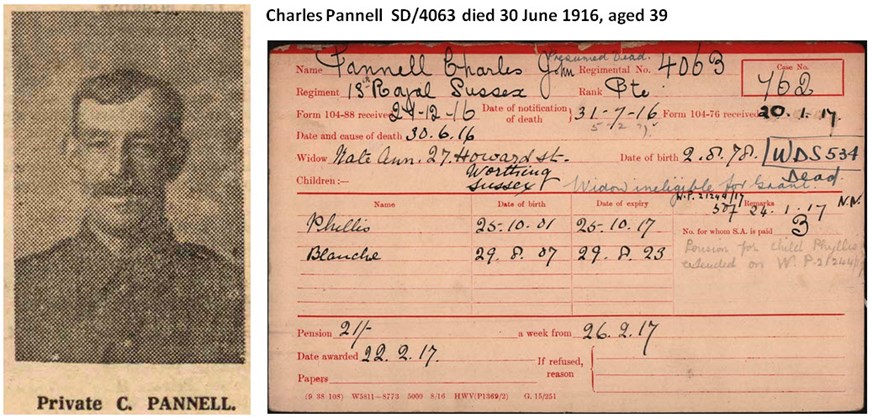

- Charles, the eldest son, an agricultural labourer like his father, married Kate Ann Tulley in 1898 at Steyning and they raised a family of three daughters.

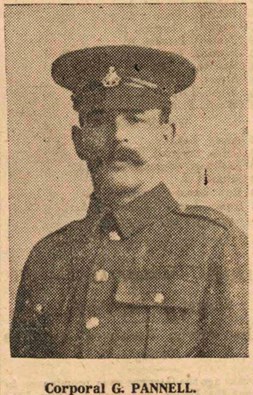

- George, a bricklayer, married Eliza in 1903 and they had 3 sons.

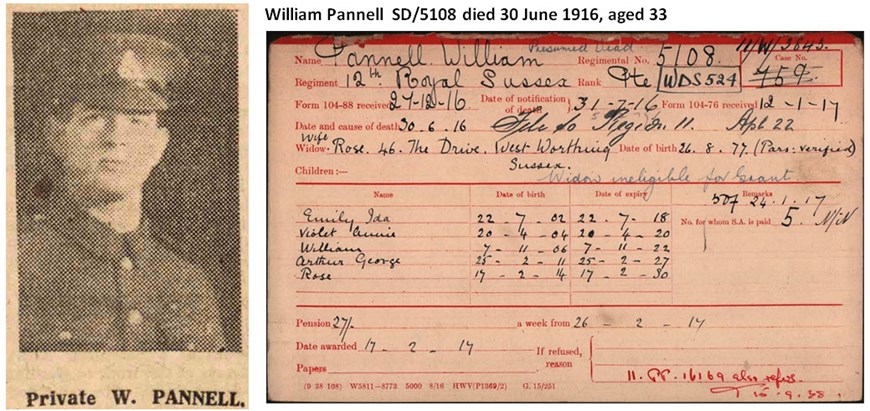

- William married Rose in 1902 and they had three daughters and two sons.

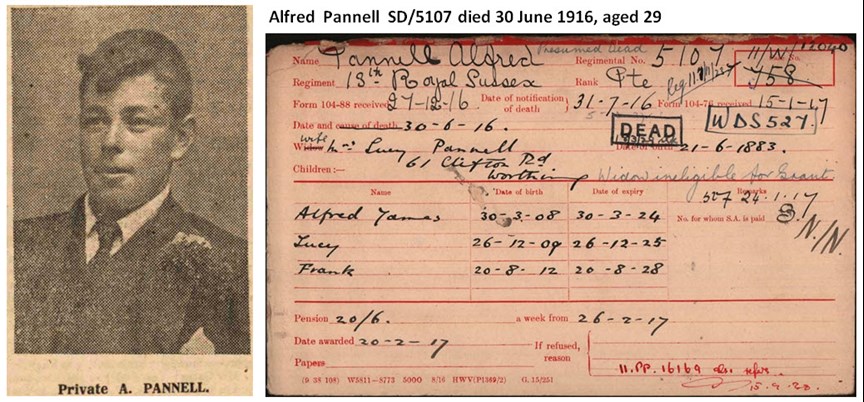

- Alfred, the youngest son, married Lucy Packer in 1907 and they had two sons and a daughter.

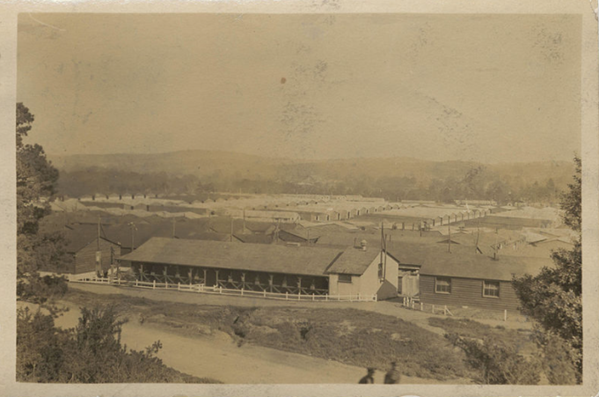

In 1915, Alfred enlisted at Worthing with the Royal Sussex Regiment, 13th Battalion. His three brothers, Charles, George and William, also signed on with the Royal Sussex (William being in the 12th Battalion). The brothers' battalions formed part of the 39th Division. This was a Kitchener’s Army formation, which had been formed in mid-1915 and trained at Witley Camp, near Guildford.

In the senior brigade (116th) there were the three ‘pals’ battalions: 11th, 12th and 13th Royal Sussex Regiment. They were otherwise known as the 1st, 2nd and 3rd South Downs battalions, and locally in Sussex as 'Lowther's Lambs' after Lt-Col Claude Lowther MP, who had initially raised them in 1914.

Recruited from all over Sussex, there were specific companies drawn from Sussex towns - such as Bexhill, Eastbourne and Hastings – and as such represented a good cross-section of the community from this part of the county.

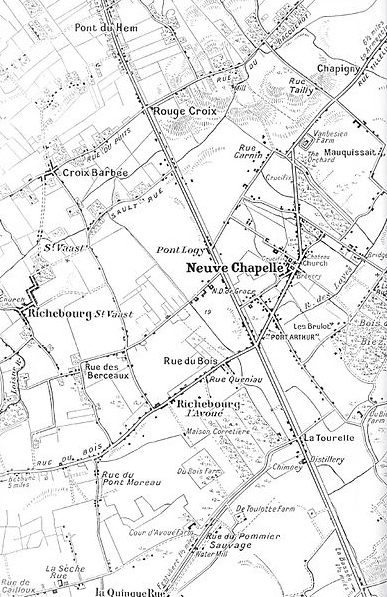

They crossed to France on 5 March 1916 with the rest of the division, and had served in the Fleurbaix and Festubert sectors before taking over the trenches at Richebourg.

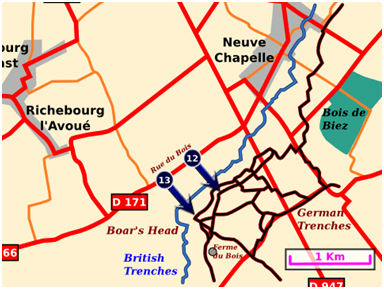

In June they learned that their battalions would be taking part in an attack on the Boar’s Head at Richebourg, a diversionary strategy intended to draw German attention and resources from the location of the ‘Big Push’, planned to take place further south, on the Somme. The plan for the diversionary attack was to launch a two-battalion attack, with a third in reserve. The leading units would ‘bite off’ the German salient known as The Boar's Head, and enter the German lines as far as the support trenches, thus establishing a new front line. The 39th Division was chosen to carry it out.

Major General R. Dawson, commanding the 39th, decided his senior brigade would be used, and the South Downs were selected given their good reputation and cohesion as a unit. The 11th would lead, with the 12th on its right, and the 13th in reserve.

On 23 June 1916, the 116th Brigade came out of the trenches and began training behind the lines. Although they were working with a replica of the ground that they would be crossing, none of the units involved was totally familiar with the terrain. During training, the plans were changed such that the 13th would head the attack. The first sense of alarm came following the 12th and 13th battalions arrival opposite the Boar’s Head. Observing through trench periscopes, officers of the battalions noticed the Germans had erected signboards on their parapets which read ‘When are you coming over Tommy?’. The bombardment had acted as a calling card, and it was clear the enemy was expecting them. Bad weather had forced a postponement of the opening of the Battle of the Somme to the 1st July and the three Sussex battalions found themselves hanging on in the front lines waiting for the new Zero Hour scheduled for the small hours of 30 June 1916.

At 0250 hours on the 30 June the preliminary bombardment of the German positions began and fifteen minutes later the leading troops climbed over their parapet and began the assault on the Boar's Head. On the left the 12th Battalion moved out into the smoke screen that was supposed to help keep them covered but tended to add to the confusion as opposed to alleviating it. As soon as the bombardment had finished the German defenders were up and out of their trenches, machine guns at the ready. Officers fell but the 12th continued on through the uncut wire and into the German positions. They managed to take the front line trenches and pushed on to the German support trenches.

Here they thought that they would find the 13th Battalion but the right flank of the attack had already failed. The smoke had completely thrown the attacking waves of the 13th Battalion and instead of advancing against the German lines, some had initially wheeled right and were badly caught with their flanks open to the murderous fire of the machine guns. The attacking soldiers could not see where they were going in the smoke and the defenders were not intent on picking people off. All they had to do was fire for all they were worth out towards the British lines. Those soldiers that did reach the German wire found, as had the 12th, that it had not been cut by the bombardment. After a couple of hours, German counter-attacks forced them back and the whole position was abandoned with heavy losses.

The cost of this diversionary attack was a hint of things to come on the following day. As the remnants of the three South Downs battalions came out of the line the full scale of the losses slowly became apparent.

As roll calls were made, it emerged that the total casualties for the morning's fighting were 15 officers and 364 Other Ranks killed or died of wounds, and 21 officers and 728 Other Ranks wounded; nearly 1,100 South Downers. That would amount to about 60% of those who had gone over the top only five hours beforehand. It became known as 'The Day Sussex Died'. Many veterans of Richebourg spoke of this attack as the ‘butcher’s shop’.

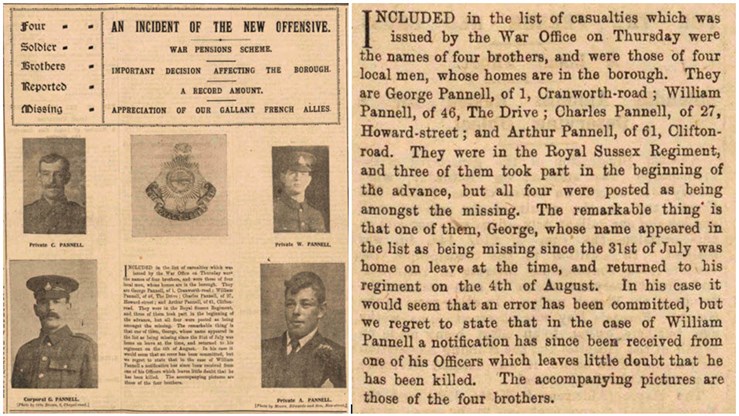

All four Pannell brothers were reported missing in the action and were presumed dead. The deaths in action of Charles, William and Alfred were later confirmed. However, at the time of the attack, George had been on his way home on leave to the surprise of his family. No sooner had they recovered from the shock of seeing him than he was ordered back to the Front, returning to his regiment on 4 August.

After the war, none of their graves could be found and their names were listed together on the Loos Memorial to the Missing on Panel 69 to 73.

We cannot begin to imagine the reactions of their mother, wives and children on receiving the telegrams, notifying them that their loved ones were missing in action, presumed dead.

And what of George? He survived the war and he and his wife Eliza raised a family of six children. He died in 1967, aged 87.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to the following people for their help and permission to use of extracts from their work:

- Malcolm Linham for first spotting this story in the Pension Records Cards

- Tom Wye for information on the three brothers

- Paul Reed for an account of the attack on The Boar's Head

- Simon at http://www.webmatters.net/index.php?id=1841 for an account of the attack

- Martin Hayes, West Sussex County Council Library Service & Johnston Press

- Katie Bishop, West Sussex Records Office

Additional Reading:

John Baines 'The Day Sussex Died: A History of Lowther's Lambs to the Boar's Head Massacre’ (2012)

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles