The Low Moor Munitions Factory Explosion

Monday, August 21 in 1916 was a fine and sunny day, but would be remembered in the area of Low Moor - which is a small town to the south of Bradford, in West Yorkshire - for many years. However, over the decades, the memories of this day have faded and the unimaginable horror that took place is now largely forgotten.

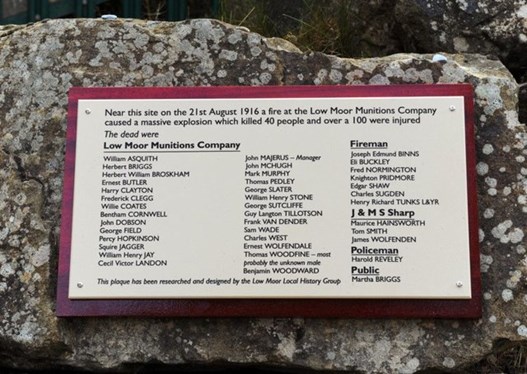

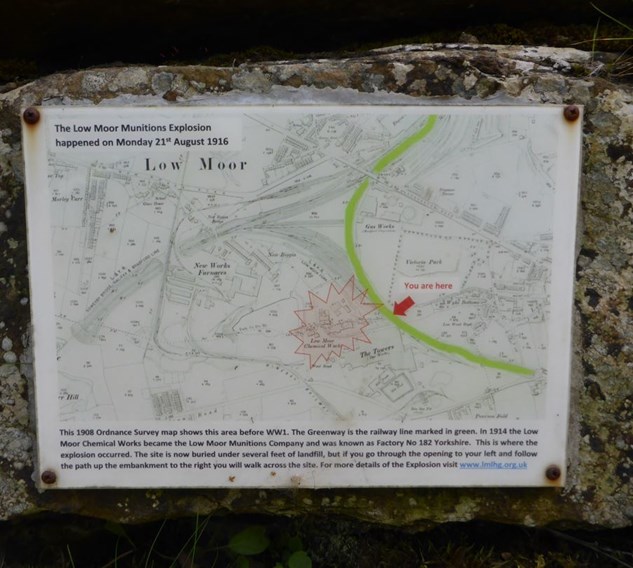

A clue as to the events of this day can be found to the side of a cycle-path that used to be a line of the Lancashire & Yorkshire railway. This path is the Spen Valley Greenway.

While the war raged many munitions factories up and down the country were working at full capacity. That at Low Moor, was no exception. The workers here produced picric acid which was a vital component in the explosives that was needed for the war effort.

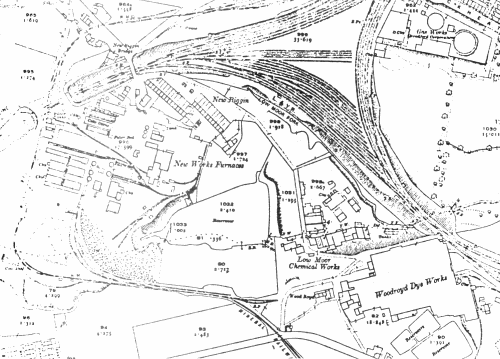

The Low Moor Chemical Company had been producing picric acid for some time; during the course of the war the factory was taken over by the Ministry of Munitions and renamed as Factory No, 182, Yorkshire. By 1916, more than 250 men and women were producing around 200 tonnes of picric acid per week.

On 21 August 1916 the factory had in stock around 30,000lb of picric acid which was awaiting sampling and then shipment. The adjoining Lancashire and Yorkshire railway line was conveniently placed for the transportation of war materials and finished goods. This railway line fed into another of other routes which criss-crossed the country in these pre-Beeching times.

On 21 August, no doubt as he did most days, James Broughton was moving 11 uncovered drums from a drying shed. However on this day, at around 2.25pm, a fire started. Mr Broughton said he heard a 'sizzling noise' while unloading a drum and then saw some acid bursting into flames, which was so violent it knocked him to the ground.

According to reports published by the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society, the fire spread quickly into the packing shed.

Percy Nudds later reported he saw the packing shed in flames from his nearby confectionary shop on Cleckheaton Road. He realised an explosion was coming and at around 2.45pm this is exactly what occurred. The packing shed exploded, with bricks and other debris falling over a wide area. One large lump of metal landed in Scholes, around a mile away.

A witness, Mrs A Hood, was working on the top floor of Cannon Mills in Great Horton (some three miles away) when the explosion happened. She subsequently described the event:

"We felt the vibration, not knowing at first what it was.... Well, we rushed into the centre of the room, all looking questioningly at each other, none of us knowing the answer.... Our coats which were hung along a wall started swaying.... After a minute or two we saw an orange cloud coming up over the trees in Horton Park. 'Oh!', I said, 'It looks like Chemical Works at Low Moor'."

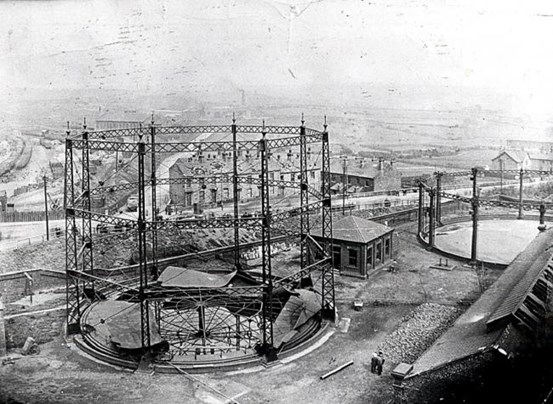

Around 30 minutes later there was a double explosion. This may have been when a large gasometer containing 270,000 cubic feet of gas was ruptured by falling debris (this was located at the adjoining North Bierley Works in Cleckheaton Road). The escaping gas quickly ignited and the heat from this blaze could be felt almost a mile away.

In the nearby railway sidings almost 30 carriages and wagons were destroyed and 100 seriously damaged.

Damage to surrounding areas was immense, with windows being blown out in all homes for at least two miles from Low Moor. Roofs were damaged, ceilings caved in. For a number of days numerous homes were not habitable -residents were forced to camp out in fields or live with relatives. Some properties were completely demolished by the blast.

The deafening narture of the blast is evident by the fact that it was heard in York which is 35 miles away.

The first fires inside the plant were tackled by the factory's own fire brigade. John Majerus, the manager of the works directed the Company's firemen but then disappeared for several hours. He was next seen crawling out of the wreckage on his hands and knees. He died that night at home.

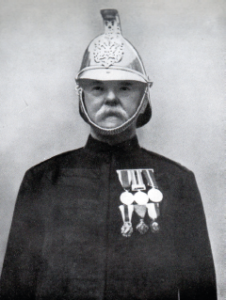

Firemen the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway also helped. (The L&YR had small numbers of men employed as Firefighters in Locomotive Fire Brigades). Also on the scene were firemen from Odsal - a suburb of Bradford only two miles away. As these men, under the command of Station Officer Sugden, approached they witnessed the first explosion.

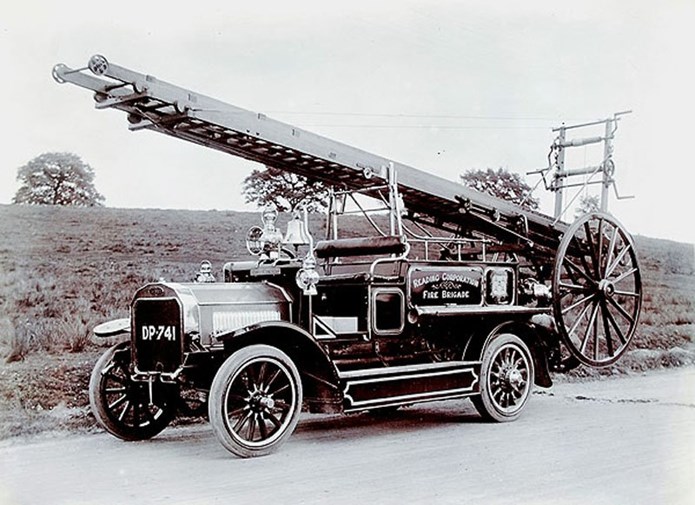

The city of Bradford's Central Fire Station was alerted at 2.33pm, and eighteen men led by Chief Officer Scott set off in their newly-acquired fire engine, which was named 'Hayhurst'.

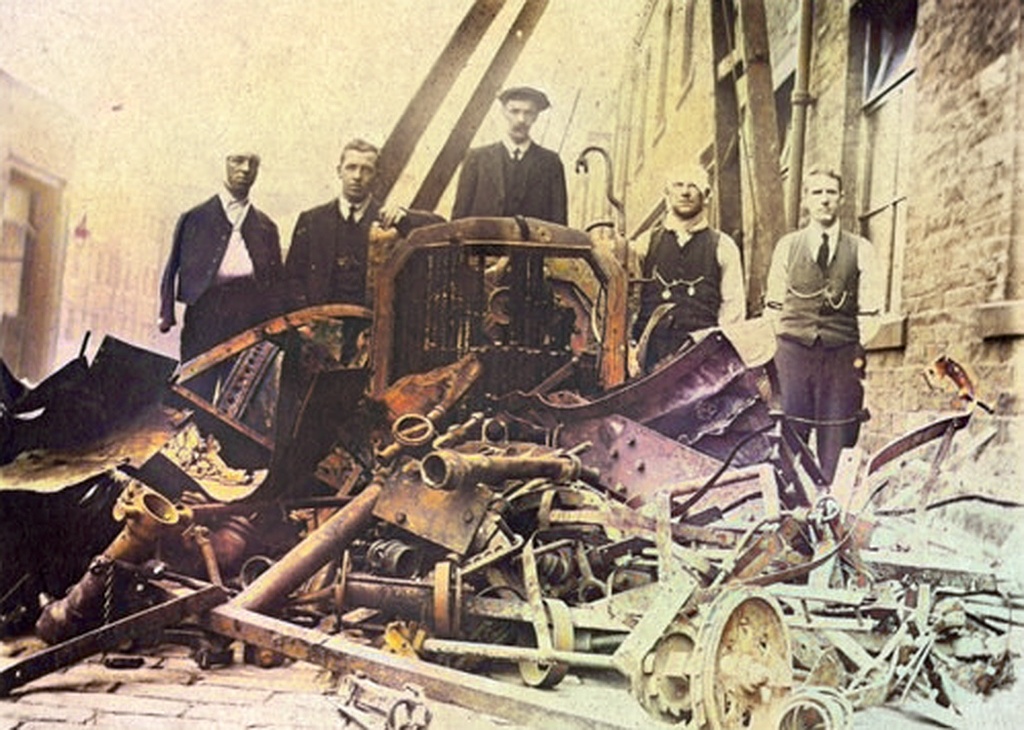

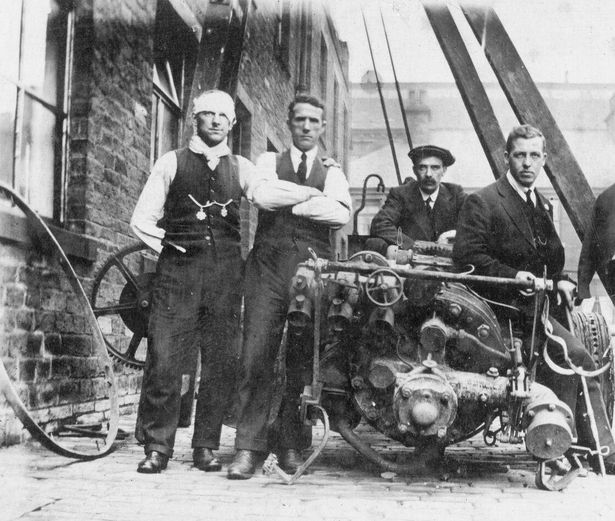

'Hayhurst' was stood thirty yards inside the factory gate. Its crew were preparing to connect the engine's hose to the hydrants when a major explosion occurred. This killed six firemen, two from Odsal and four from Nelson Street. The 'Hayhurst' was blown apart. Some components of the engine were found in Heckmondwike railway station, nearly five miles away. Some of the bodies of those firemen killed in this explosion could only be identified by the numbers on their axes.

The initial casualty figures given were 34 people killed and 60 injured. These figures applied only to the factory, but elsewhere many more were injured by flying glass and debris. The number of dead later rose to 40 and those injured to around 100.

The youngest victim was 17-year-old Maurice Hainsworth, a dyers labourer of Hardy Street, Scholes, Cleckheaton.

Frank and Ida Clarkson were getting married on this day. The couple were leaving a nearby chapel when the second blast happened. The waiting horses bolted and Ida suffered cuts to her face from broken windows.

One eyewitness recalled seeing dogs running away from the scene in all directions and later to be found in Halifax (six miles away), Huddersfield (8 miles away) and even Wakefield (12 miles away). Explosions continued for two days and the fires were still not out three days later. It was estimated that 2,000 houses suffered damaged with 50 being badly damaged.

The damage was huge, and the loss of life considerable, but newspapers were severely limited in what they could report due to the wartime censorship. Despite this, the local newspaper was able to headline the news the following day as can be seen below.

A report in the Yorkshire Observer, 48 hours after the explosion, stated

'...The loss of life was not so serious as at first seemed probable, and this was due to the fact that the fire which preceded the first explosion gave sufficient warning to enable most of the men and all of the women workers to get out of danger.'

An inquest into the tragedy, held in September 1916, looked into the suggestion that German spies or saboteurs might have been responsible. This gained a degree of credibility because, on the day of the explosion, some of the workers who were notable by their absence were Belgians who had settled in the area on the outbreak of the war. After questioning those who were not at work, however, this possibility was ruled out.

The inquest and an Inquiry showed that there had been a number of contraventions of what we would now call 'Health and Safety'. It was established that a storage hut contained more than twice the quantity of picric acid allowed by the licence and containers used for moving explosives were not covered as they should have been. There is no doubt, though, that wartime emergency production was overlooked with the need to make explosives for the Battle of the Somme that was raging.

An accident report concluded that the explosion was probably caused by the ignition of iron picrate which was on the top of the drums.

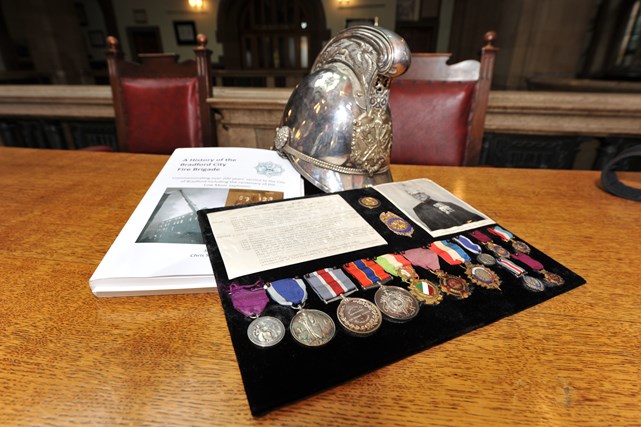

The firemen who lost their lives were buried on 26th August 1916 at Scholemoor Cemetery, Lidget Green. On 4th March 1924 the Lord Mayor of Bradford unveiled a memorial to them, the cost, £1,200, being raised by public subscription.

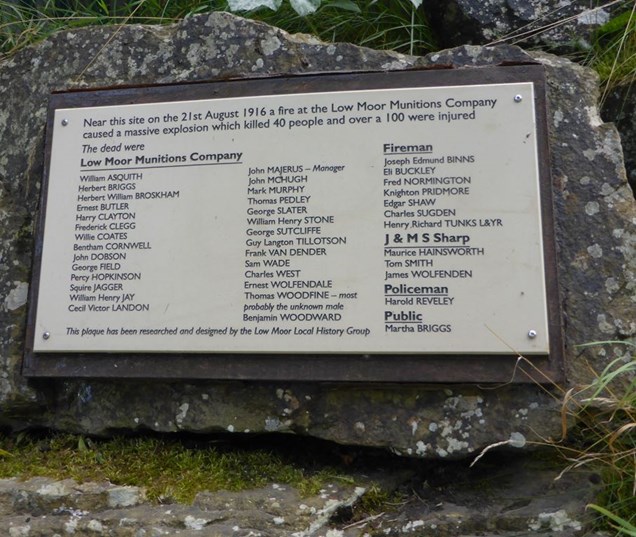

The workers from the plant did not have a dedication to them until 2016, the 100th anniversary, when a plaque was unveiled near to the former plant on the Spen Valley Greenway.

The Low Moor History Group paid for the plaque and researched all the dead as wartime restrictions had meant that not all of the dead had been publicly named.

The dead were listed on the plaque as 28 workers from the plant, six firemen, three workers from Sharps Dyeworks, a policeman, a Lancashire & Yorkshire fireman and a member of the public called Martha Briggs.

The site today is now a nature reserve. It was used for many years as landfill.

To find out more visit The Low Moor Local History Group

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles