Project Hometown

Hot on the heels of Project ALIAS, Project HOMETOWN was launched in April 2020 and would prove to be an even bigger project than ALIAS. But with the completion of ALIAS several months ahead of projections and the continuation of severe restrictions due to the Covid-19 situation, it became obvious that that an opportunity existed to further expand the potential value of the Pension Records saved from destruction by The Western Front Association.

The purpose of Project HOMETOWN was quite simple – to ensure that as far as possible the addresses on the Pension cards were appropriately reflected in the ‘tagging’ of each card (the detail provided in the information box). The ‘tagging’ is needed when undertaking a search – if the ‘tag’ is missing or incorrect the card won’t come up in a search. This ‘hometown’ exercise was not to extend to street level, but to concentrate on the town detailed on the card. While it was recognised at the outset that the addresses on Pension cards were not necessarily the soldier’s hometown, in many cases they were…and in those cases where not, there was often a family link in that a widow may have returned to her home area. Nonetheless, it was felt that improving this information would be of benefit to researchers and family historians in the future.

The process was very similar to that employed in ALIAS – with volunteers going through each drawer and identifying where the current information provided was incorrect. Whilst a number of volunteers migrated from ALIAS to HOMETOWN, a substantial number of new volunteers joined HOMETOWN and in total, around 130 volunteers have played a role in the project. Whilst the process was simpler than ALIAS (there was no need to break the work into phases), the output was far in excess of the ALIAS project because a significant number of cards had addresses written on them.

But there were also a number of potential complications which affected the number of returns from volunteers going through the drawers. These were -

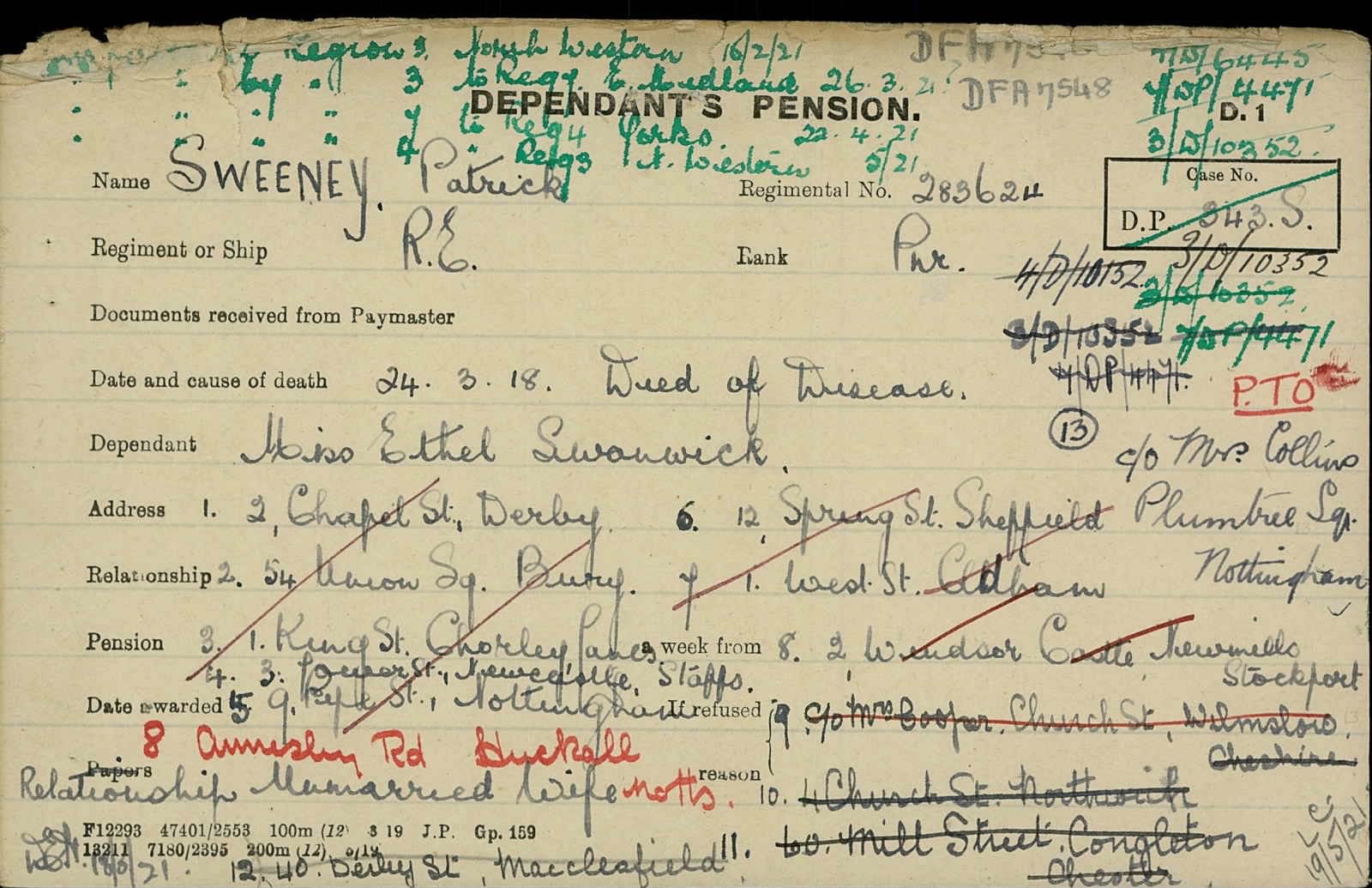

1) The original handwriting on Pension Cards could range from ‘copperplate’ to almost illegible.

This clearly caused issues for Ancestry ‘taggers’ but additionally, a significant number of cards could have more than one address, with one (or more) scored out. Only one address would be identified in the original ‘tagging’ process.

Whilst there have been several instances where around five or six additional addresses may have to be discerned and then input, in the majority of cases, only one or two were required. The record for the number of addresses on one card was twelve.

2) There could be only a street name or partial address on the card. Many volunteers went to great lengths to research such cards to identify the town, using resources through the CWGC, Ancestry and other such websites. It was also sometimes possible to identify more that one card for a man, where the address might have been written in full on another card.

In the case of the card depicted here, the address was actually in India, and identified through a marriage record and burial record showing that the soldier was buried in Ootacamund, Madras.

Tracking down some of the more obscure addresses captured the interest of many volunteers – in the case of one card which indicated ‘No Place’ as an address, until further research identified that there is indeed a ‘No Place’, near Stanley in County Durham.

3) London addresses posed the project some issues as from the outset it was considered that a tagging of ‘London’ would not be particularly helpful to future researchers.

After much thought, it was determined that we would seek to identify the ‘district’ in which the address was situated. The discovery that London postcodes had not changed in over 100 years also provided the opportunity to tag districts with a postcode – for example, Bethnal Green E2. Luckily, there were a number of ‘London experts’ who could assist in the identification of a discernible district in the city. This task was complicated by the fact that several streets – notably Old Kent Road, Caledonian Road and City Road run through several districts.

In the case of other cities outside London, these were often tagged with simply the city, although the card might detail a district within that city. It was decided that where possible, these districts would also be added to the tagging to assist future researchers.

4) Finally, the original tagging may simply have been incorrect or misspelt– instances of this were relatively simple to tackle, providing that the original writing on the card was legible.

The primary purpose of HOMETOWN was to assist researchers and local historians to track down the men in their locality – although the project will only be as good as the information recorded 100 years ago. Members using towns to research soldiers may need to use alternative suburbs etc to identify all men that they may be seeking.

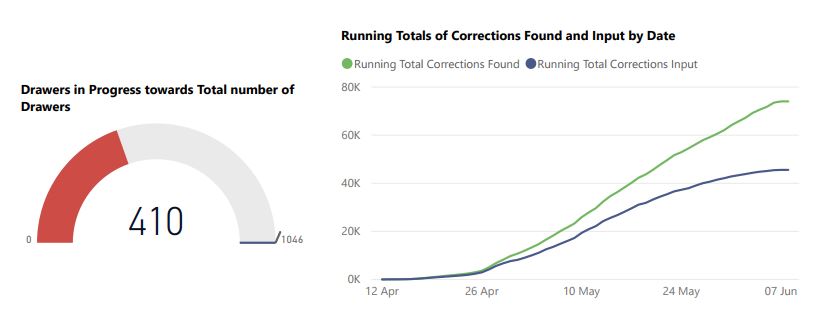

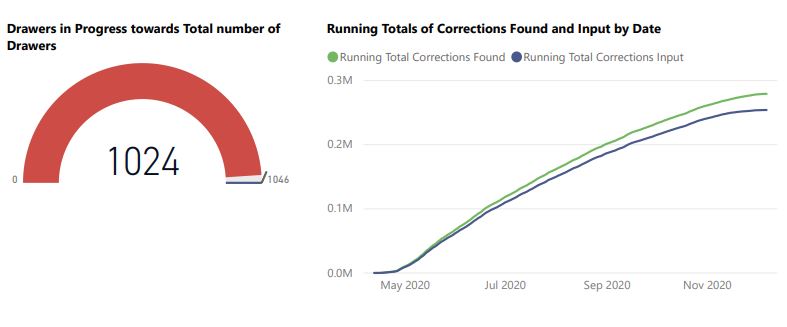

The Soldiers Died cards totalled 933,145 across 1046 drawers, 22 of which are awaiting work by Ancestry to enable these to be completed.

The percentage of returns per drawer has averaged at 30.5% - resulting in 8 team spreadsheets ranging from just over 10,500 returns in the smallest team to over 88,000 returns in the largest. Across all teams, a total of just under 280,000 returns were made, of which a small proportion might involve multiple tagging entries required to some cards.

Each team leader identified a small sub team of ‘correctors’ who were tasked with effecting the amendments to tagging

Progress was monitored weekly throughout the project with the aid of a visual ‘dashboard’ circulated to team leaders and then cascaded to team members.

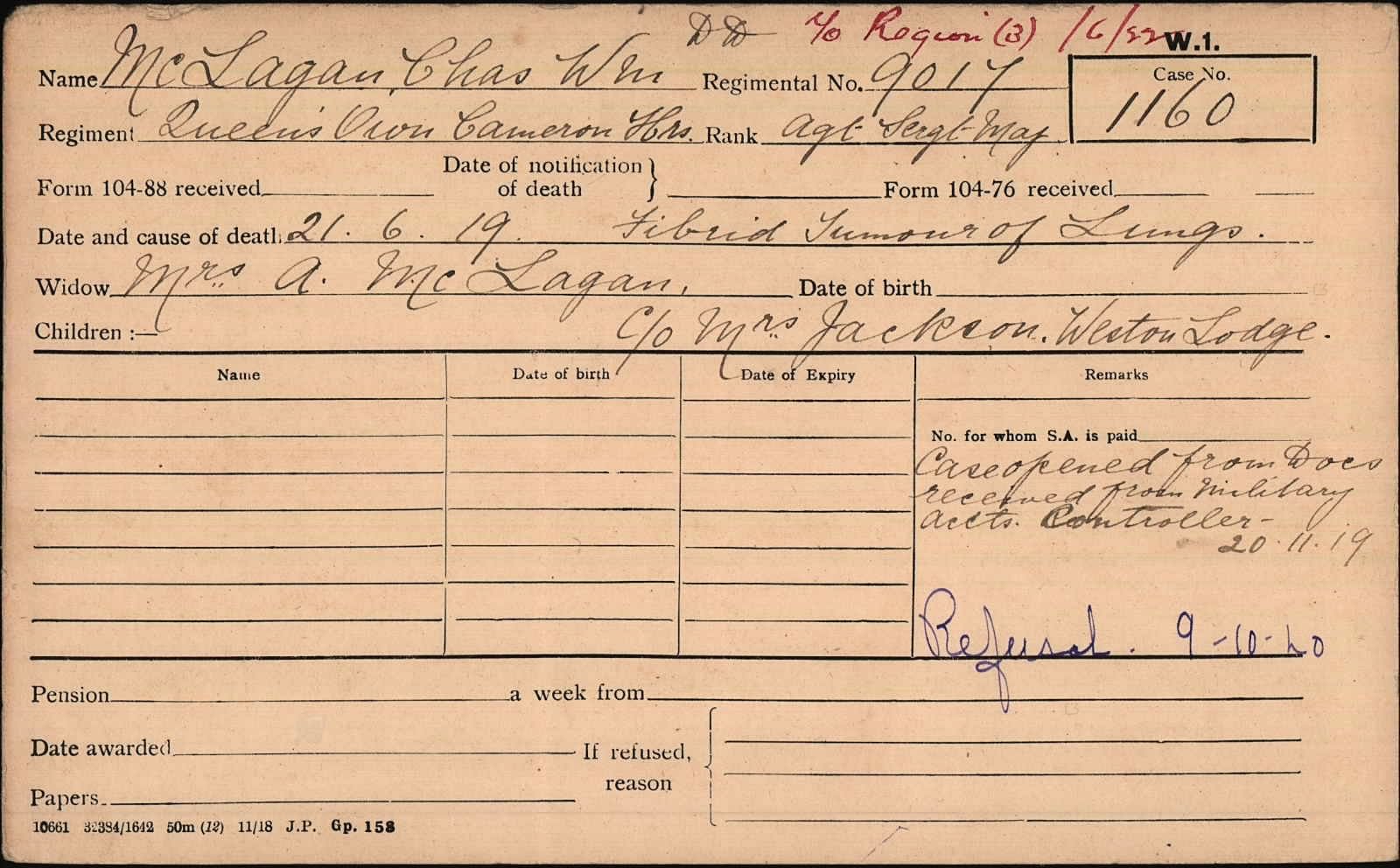

The process of going through each card in this dataset has highlighted the additional information that they can provide for researchers. A number of cards have intriguing causes of death annotated on the card. There are several ‘shot at dawn’ annotations but it is some of the less usual descriptions that have prompted further research on the part of volunteers in this project.

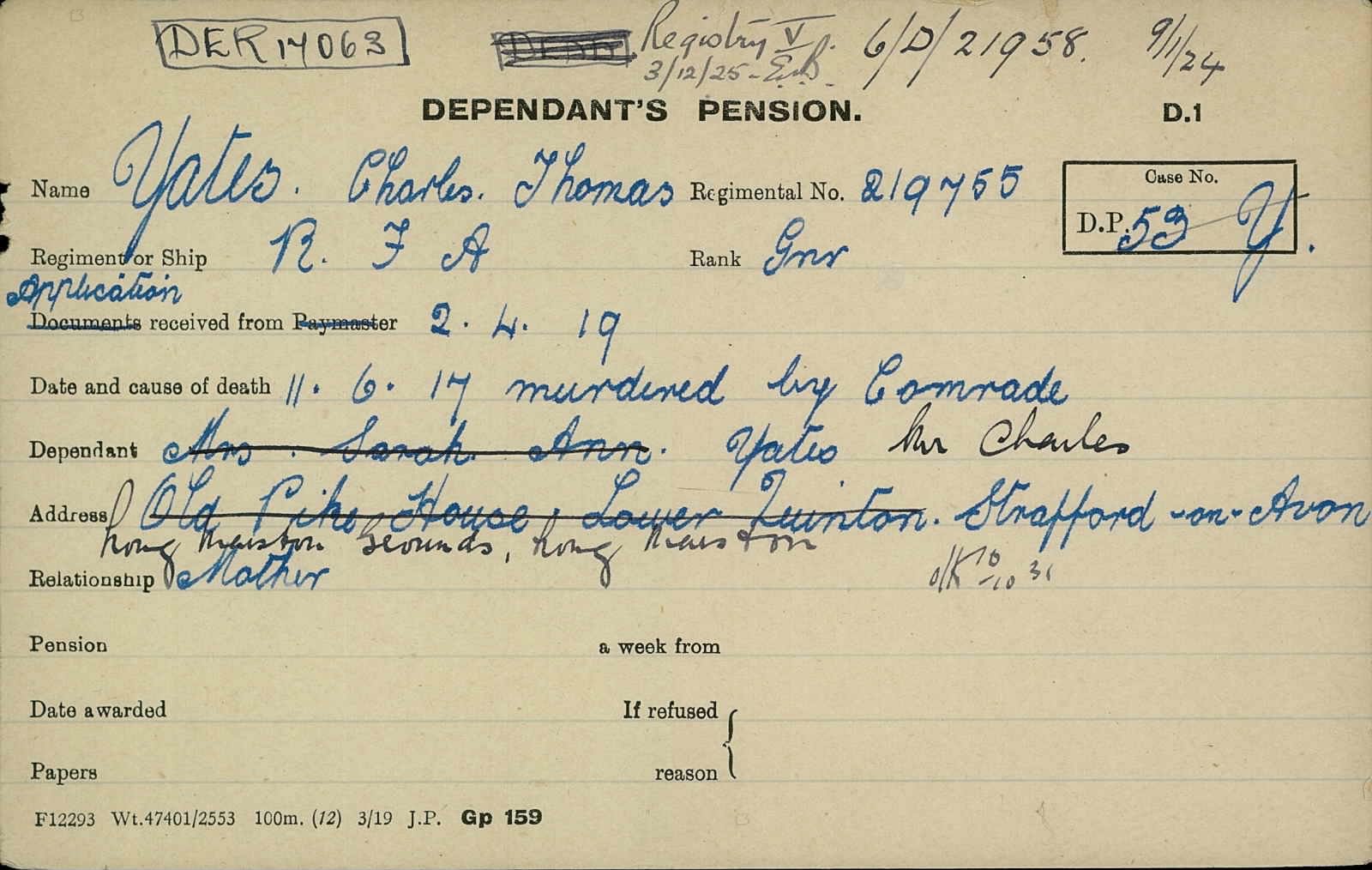

An example of this is the card for Charles Thomas Yates which indicates that he was ‘murdered by a comrade’ on 11 June 1917.

Research has identified that Yates was walking with Driver Arthur Peacock when Peacock pulled out a razor and cut Yates’ throat. Charged with murder, Peacock was subsequently found to be insane when the case went to court and was sent to Broadmoor where he died of natural causes in 1934.

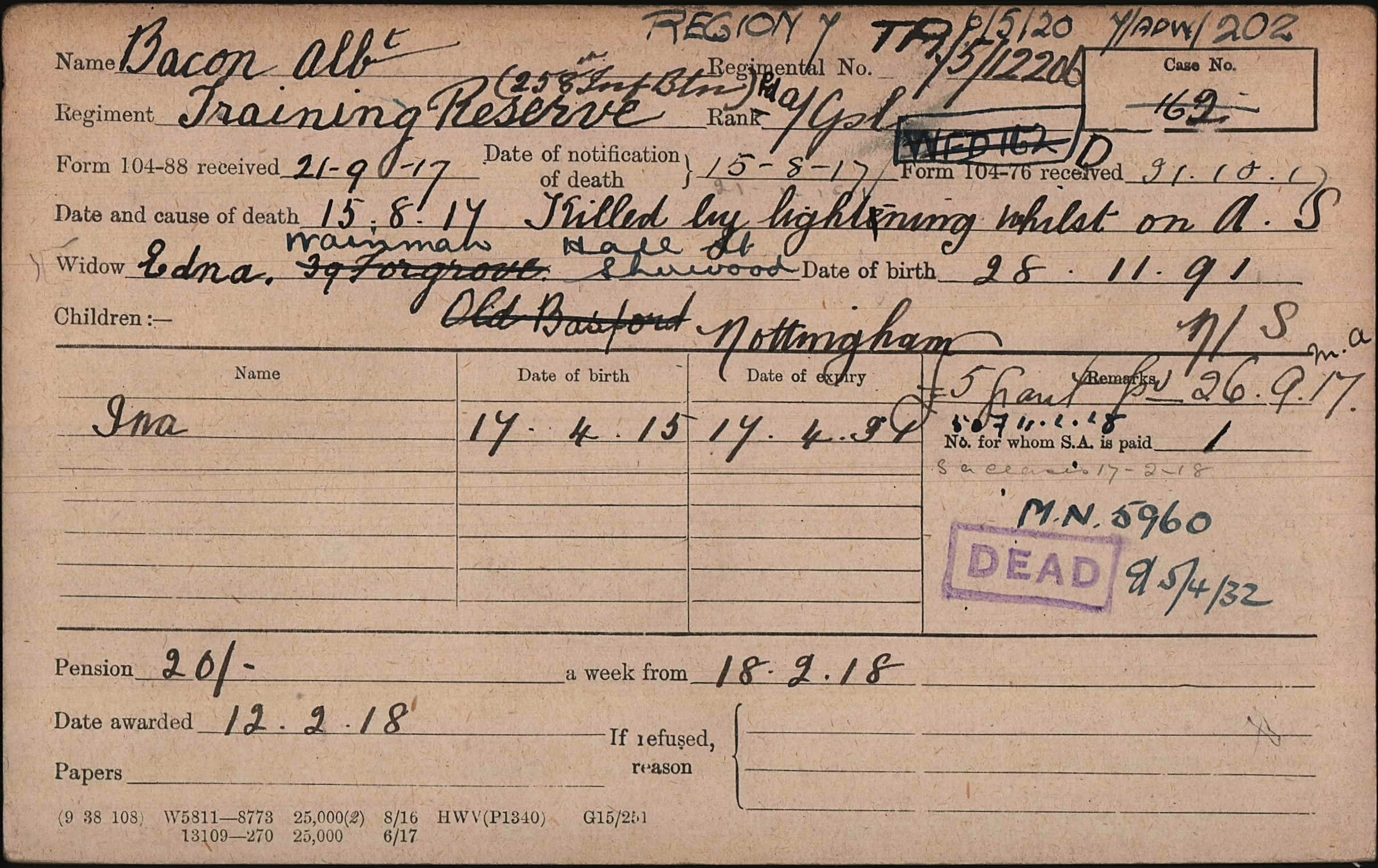

Another card indicated that the cause of death was ‘struck by lightning’.Acting Corporal Albert Bacon, a married man from Nottingham, with one child, was serving in the Training Reserve of the North Staffordshire Regiment when on15 August 1917 he was on a training exercise near Ipswich. During a thunderstorm, he and Sgt Powell, a single man from Stoke on Trent, sheltered under a tree which was hit by lightning. Despite efforts to save the two men, they were pronounced dead at the scene. An inquest later identified that the cause of death was due to the men being hit by ‘a thunderbolt’.

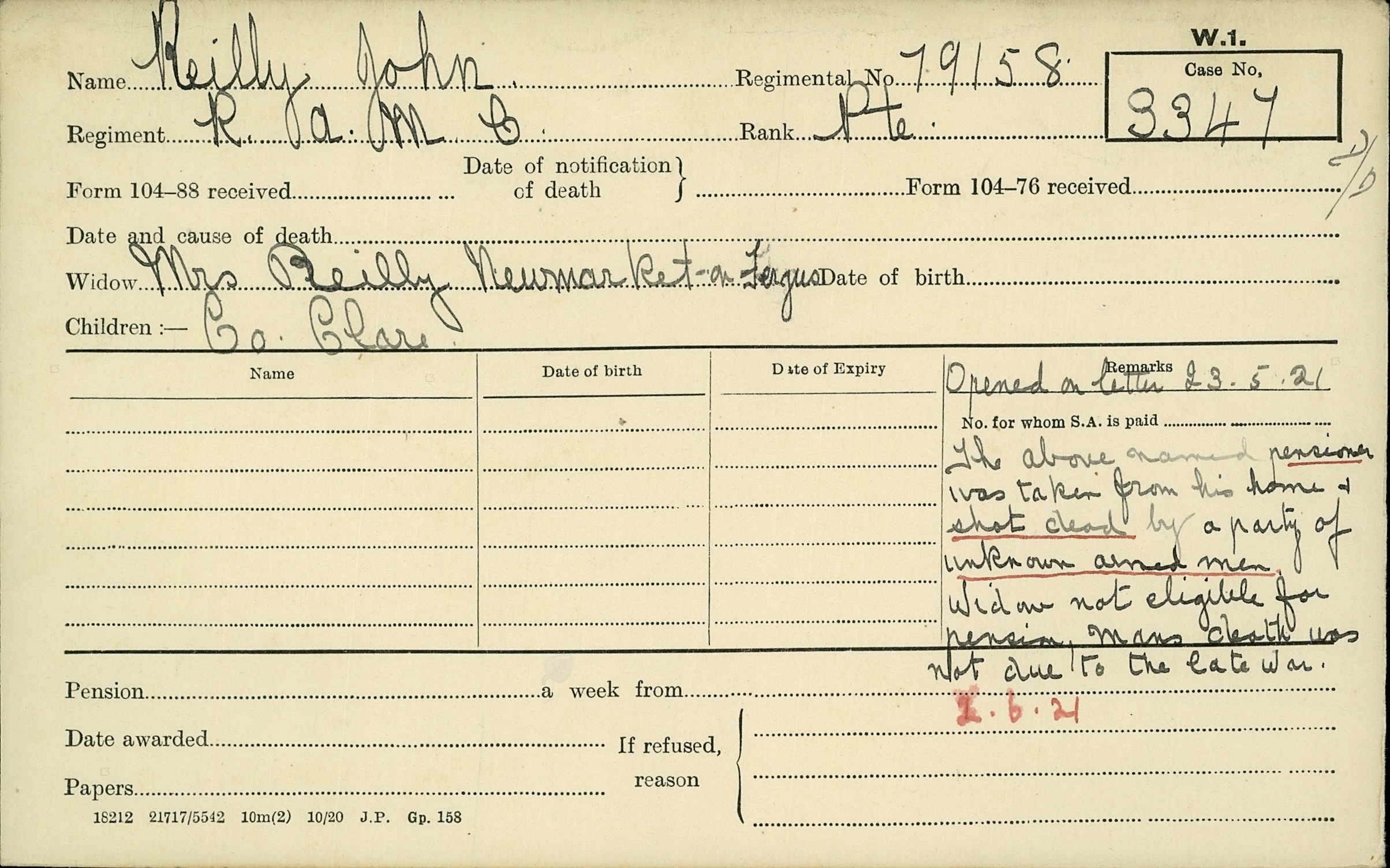

The Pension card for John Reilly indicates that he ‘was taken from his home and shot dead by a party of unknown armed men. Widow not eligible for pension. Man’s death not due to the late war’. Although his pension was stopped at the end of the week in which he died, his widow later received £1,200 in compensation from the British Government.

Further detail on the circumstances of John Reilly’s death can be gleaned from the records of the Court of Enquiry held following his death. (Many of these documents are available online). From evidence provided to the enquiry, John Reilly was involved in the ‘Comrades of the Great War’ in the area – and according to witness statements, was ‘a well known Loyalist’ and ‘known to be mixing a good deal with the Black and Tans in Newmarket’. It would appear that those tasked with carrying out his execution had no knowledge of what he was deemed to be guilty. One of the witness statements goes as far as saying ‘my part in his execution was simply in compliance with instructions issued to me by a superior officer, the Brigade C/C. He made no confession of his guilt to any of his captors and I would like to add that he met his death in a brave and dignified manner. I felt really sorry for him’.

John Reilly’s execution was one of a number of ex-soldiers living in Ireland during the period 1919 to 1921. In some cases, there appears to be more evidence that the ex-soldier was providing information to the British or to the Black and Tans but in a number of cases, the evidence is far from clear.

There will be many others where it has not yet been possible to find out more – for example, the case of Edgar Smart in the South African Native Labour Corps who was noted as ‘murdered by natives’ or the case of Owen McEntee of the Connaught Rangers ‘shot during an actual attack’ whilst a Prisoner of War.

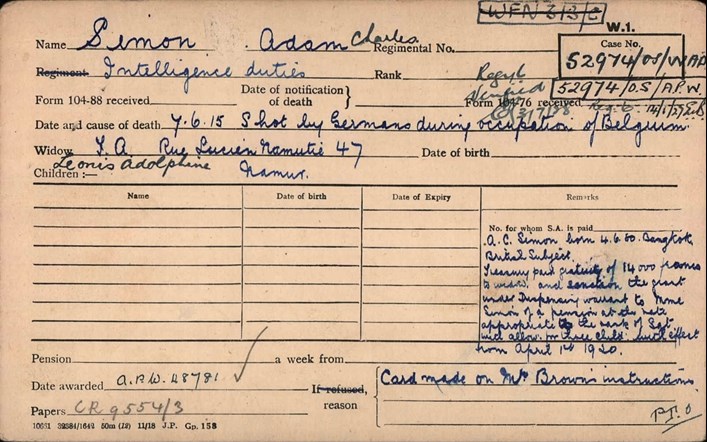

Occasionally an unusual pension card would be highlighted by volunteers in the project. Such an example is that of Charles Simon, a civilian executed for treason by the Germans in 1915. Extensive research carried out by the volunteer who noted this card has resulted in the publication of a more detailed article on the WFA website.

There is also the potential for further research on a number of cards where the dependent’s address is abroad – in some cases in perhaps unusual locations.

Having started this article by suggesting that Project HOMETOWN was the biggest project yet to be instigated by The Western Front Association, this is likely to become ‘old news’ fairly shortly as work on the newly released ‘Soldiers Survived’ Pension Cards commences.

Other Articles