A short and unequal engagement: HMS Strongbow and HMS Mary Rose

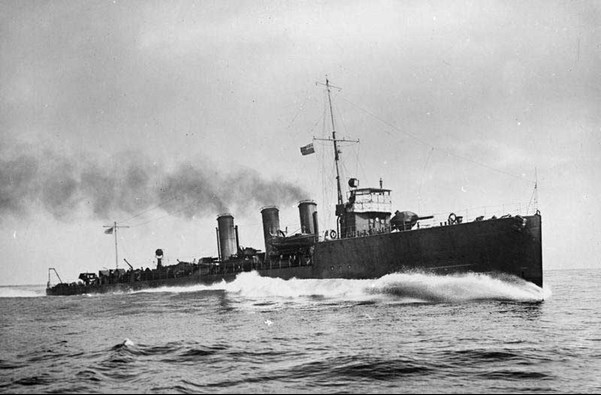

HMS Mary Rose and HMS Strongbow (two M-class destroyers) were routinely deployed on convoy duties for merchant vessels carrying coal between Scotland and Norway in 1917. The job was usually fairly mundane – described as ‘mail runs’ by one of the survivors ... but the events of 17 October 1917 would change all that.

HMS Mary Rose was the seventh such Royal Navy vessel to bear the name ‘Mary Rose’ and was built in 1915 in the Swan Hunter Yard. HMS Strongbow was launched the following year, built by Yarrow Shipbuilders on the River Clyde.

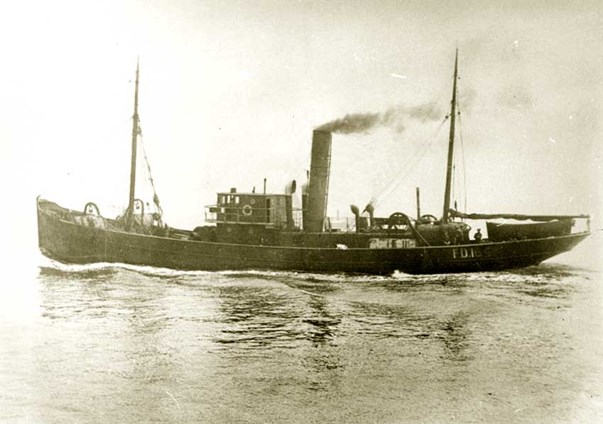

In mid October 1917, both destroyers were accompanying a convoy of merchant vessels between Lerwick and Norway, along with the armed trawlers, Elise and P. Fannon. The Elise was a Peterhead registered trawler, built in 1907. P. Fannon was built in Aberdeen in 1915 – both were originally taken on by the Admiralty for mine sweeping duties.

The lead vessel was the Mary Rose, with Strongbow captained by Lt. Commander Edward Brooke at the rear of the convoy. The convoy itself comprised twelve merchant ships – two were British, one Belgian and nine Norwegian, Danish and Swedish.

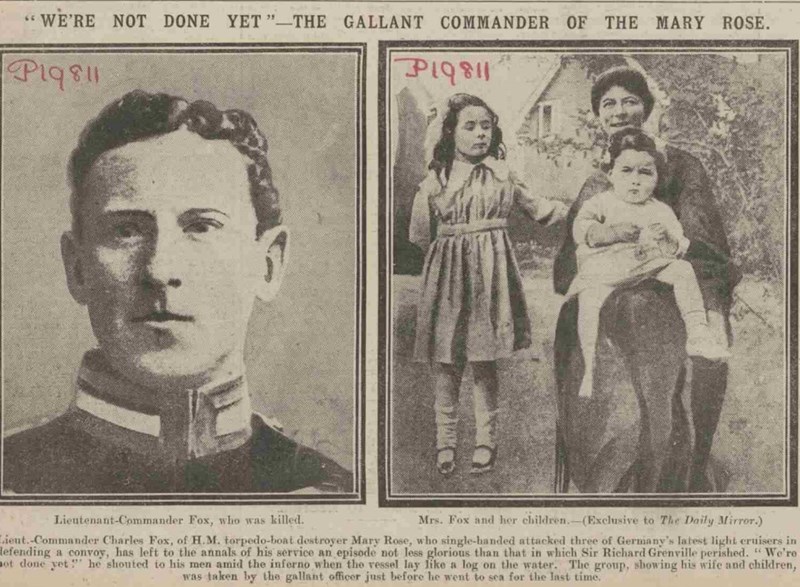

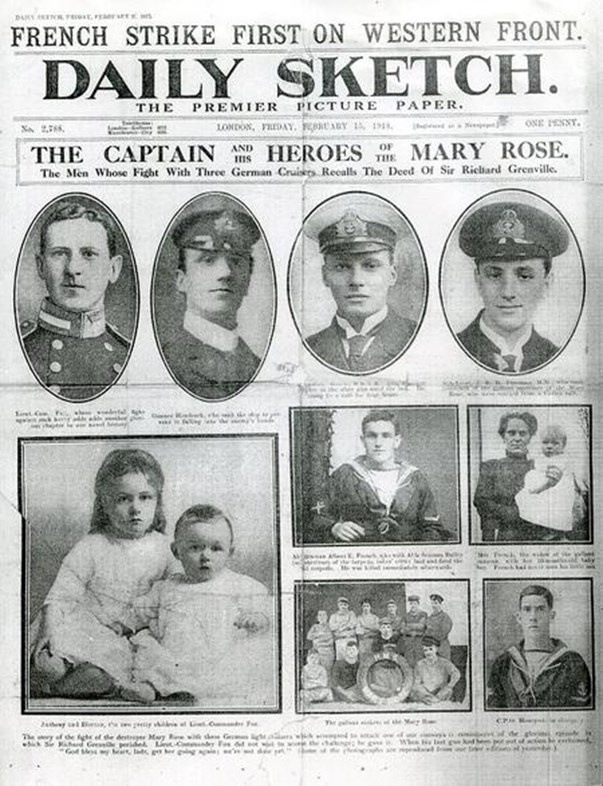

On 17 October 1917, HMS Mary Rose, under the command of Lt Commander Charles Leonard Fox, was some way ahead of the main convoy.

Lt. Commander Brooke of Strongbow was awarded the DSO in August 1918 with the citation reading

“…in command of HMS Strongbow. Fought a gallant action against overwhelming odds in endeavouring to protect a convoy. He was seriously wounded during the engagement”.

Brooke was severely injured in the ensuing fight with initial press reports suggesting that he had lost a leg and an eye. However, his injuries transpired to be less serious although he subsequently died of pneumonia on 10 February 1919. He is buried in Almondbury Cemetery, Huddersfield.

It was the crew of Strongbow who first spotted two unidentified cruisers approaching the convoy. Three signals were sent asking the vessels to identify themselves – the third of these received a badly morsed response. Although they were rigged to look like British cruisers, the vessels were, in fact, SMS Bremse and SMS Brummer of the German fleet, two fast cruisers which had hitherto been used for mine-laying, despatched by Admiral Scheer to intercept convoys of ships from Lerwick to Norway.

Lt-Commander Brooke's Strongbow prepared to open fire but the ship was hit by the opening salvo from the Germans, leaving Strongbow unable to manoeuvre. Brooke, injured in the attack, ordered the destruction of confidential papers and reports before giving the order to scuttle the vessel.

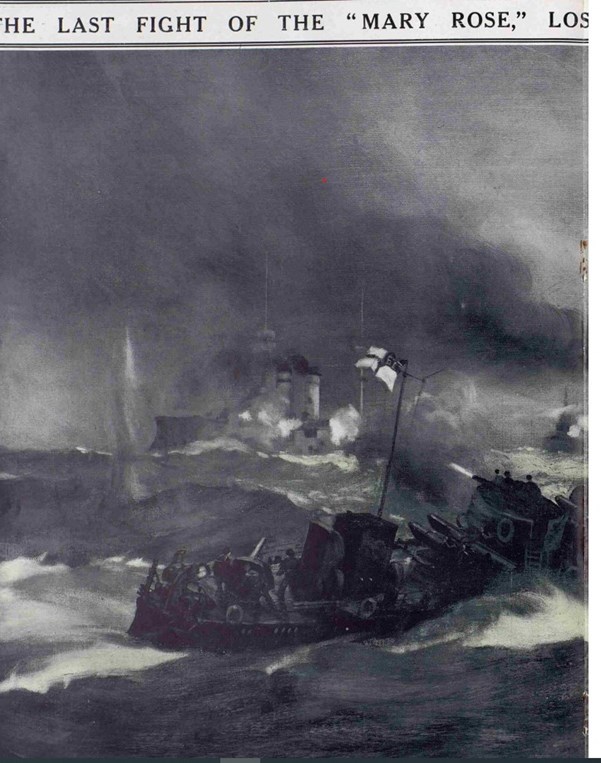

Meantime, HMS Mary Rose had turned back on hearing gunfire with Fox initially thinking that the convoy was being attacked by U-boats. Although ill-prepared to fight against such heavy odds, the Mary Rose opened fire from a range of around 6,000-7,000 yards. However, the German fire became increasingly accurate at around 2,000 yards and within a short time, the Mary Rose had to be abandoned. The plucky Elise came back to rescue survivors and some were picked up by the surviving merchant ships. Neither destroyer had been able to send any messages out about their fate.

Nine of the merchant ships were sunk, with only three steamers and the two trawlers surviving. In total, around 250 men lost their lives in this engagement. Of the Strongbow’s crew of 82, 45 were lost. All but 10 of the crew of the Mary Rose were lost. Lt Commander Fox was last seen swimming in the water. It would later be alleged that the German ships had fired on survivors in the water but this was denied. The Germans were also criticised later as they failed to rescue any of the men in the water but argued that the surviving steamers could have been expected to do so.

One boat containing 2 officers and 8 men managed to row and sail over the next two days, finally reaching the Norwegian coast. One of the survivors on this boat was Seaman John Frederick Bailey, who although injured, insisted on taking his turn at the oars.

Most of those lost from Strongbow and Mary Rose are commemorated on the Chatham, Plymouth or Portsmouth Naval Memorials but there are four buried in Fredrikstad Military Cemetery in Norway

Six are buried in Lerwick New Cemetery.

Midshipman Archibald Douglas Moir was one of the youngest casualties from the Mary Rose.

Reports in the British press following the loss of the two ships referred to the gallant action of both Commanders in engaging the German cruisers until sunk ‘after a short and unequal engagement’. Typical of the coverage is that which appeared in The Dundee Courier on Monday 22 October 1917:

“Many striking instances of British courage and humanity have been revealed as the result of the naval fight in the North Sea on Wednesday and these stand out in sharp contrast to the clearly proved callousness and cruelty of the German naval seamen. The whole affair is another case of ‘tip and run’ naval activity, and the details again show up the enemy navy in a most unenviable light…their foul work hurriedly done the German warships left the men drowning and dying and returned to Germany at full speed”.

The report went on to describe:

‘Frightful scenes on the decks of the merchant ships’.

Press reports continued well in to 1918.

The subsequent inquiry into the loss of the two ships praised the courage of both Fox and Brookes but did make some criticism of their actions in attempting to engage the enemy, suggesting that their priority should have been to summon assistance by wireless. However, it was the case that radio signals were effectively jammed by the Germans and Strongbow’s wireless had been destroyed at a very early point. The two trawlers Elise and P. Fannon were not equipped with wireless – ironically, a third trawler which had wireless was some 10 miles away, watching over a merchant ship which had been forced to drop out of the convoy.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles