Le Roi des Montagnes, the French, and Floatplanes

Author’s Note: When researching and writing a book or article the author is often left with material that is not quite relevant and/or the project is already too big to accept it. Both happened with my new book Floatplanes Over The Desert. Some stories are just too good to abandon. This is the story of one Marko, pirate/brigand/smuggler, and his island ‘kingdom’ of Tersana, wrapped around an extract from my book detailing some floatplane operations from the island of Castellorizo.

It is, in effect, the story of a sideshow within a sideshow.

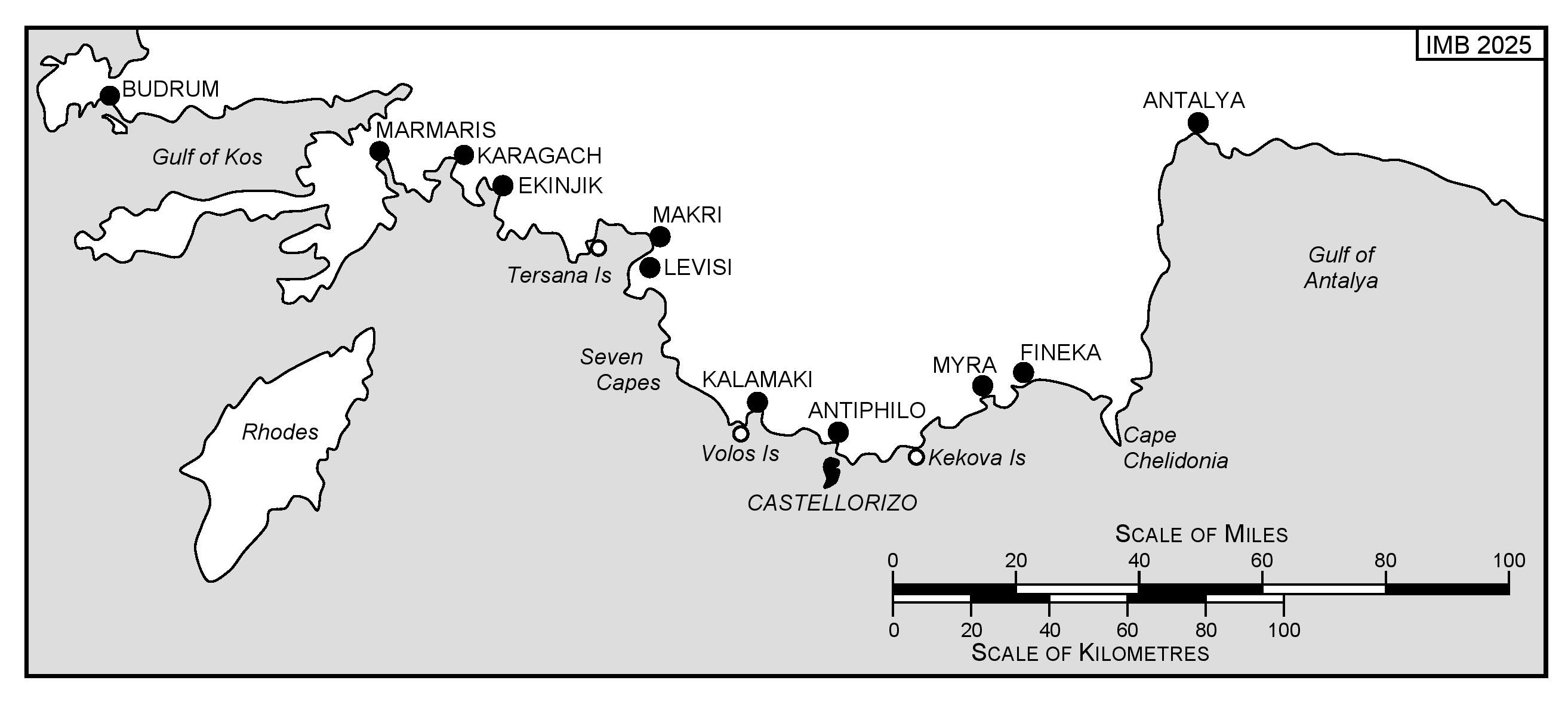

Other than a few German submarines, the French and Royal Navies enjoyed total naval supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Great War. This enabled the French to maintain outposts on small islands within cannon shot of the Turkish-held coasts. Ruad (Arwad) is barely two kilometres from the coast of what was then the Ottoman Sanjak of Tripoli, near Tartus, and Castellorizo as close to the southern coast of Anatolia. What made this latter island so attractive to the French was its location. Positioned some 125 kilometres east of Rhodes and an equal distance south-west of Antalya, the major town on the southern Anatolian coast, the island was ideally located for intelligence gathering. Numerous smaller islands east and west of Castellorizo were, at best, only loosely under Turkish control, several being used as bases for irregular Greek forces to make raids on the mainland.

Further around the coast in the Aegean these raids were often led or organised by Commander J L Myres, RNVR. He gained the sobriquet Blackbeard of the Aegean as much for his appearance as his piratical activities. But that is a story for another time. Similar raids were organized and assisted by the French based in Castellorizo, which they occupied in the final days of 1915. A local militia had been recruited by one Ioannis Lakerdis and armed by the French. Transported in French ships they engaged in several mainland raids, including the adjacent coastal town of Antiphilo [Kaş], and briefly occupied Kekova island some kilometres to the east. But this story concerns a very small island, Tersana, some distance to the north-west.

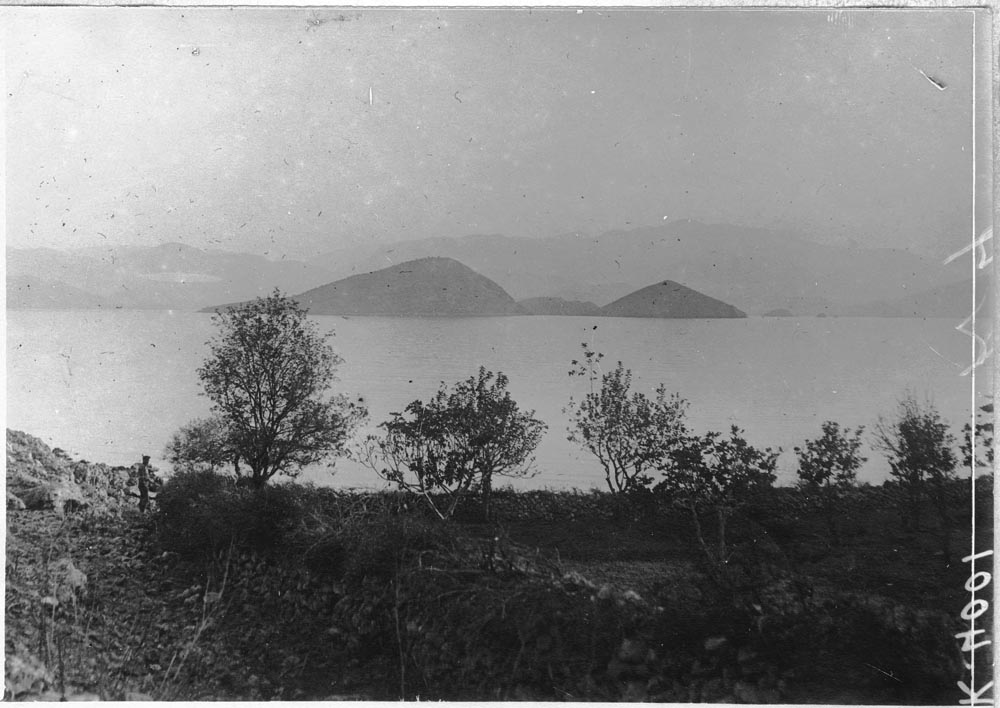

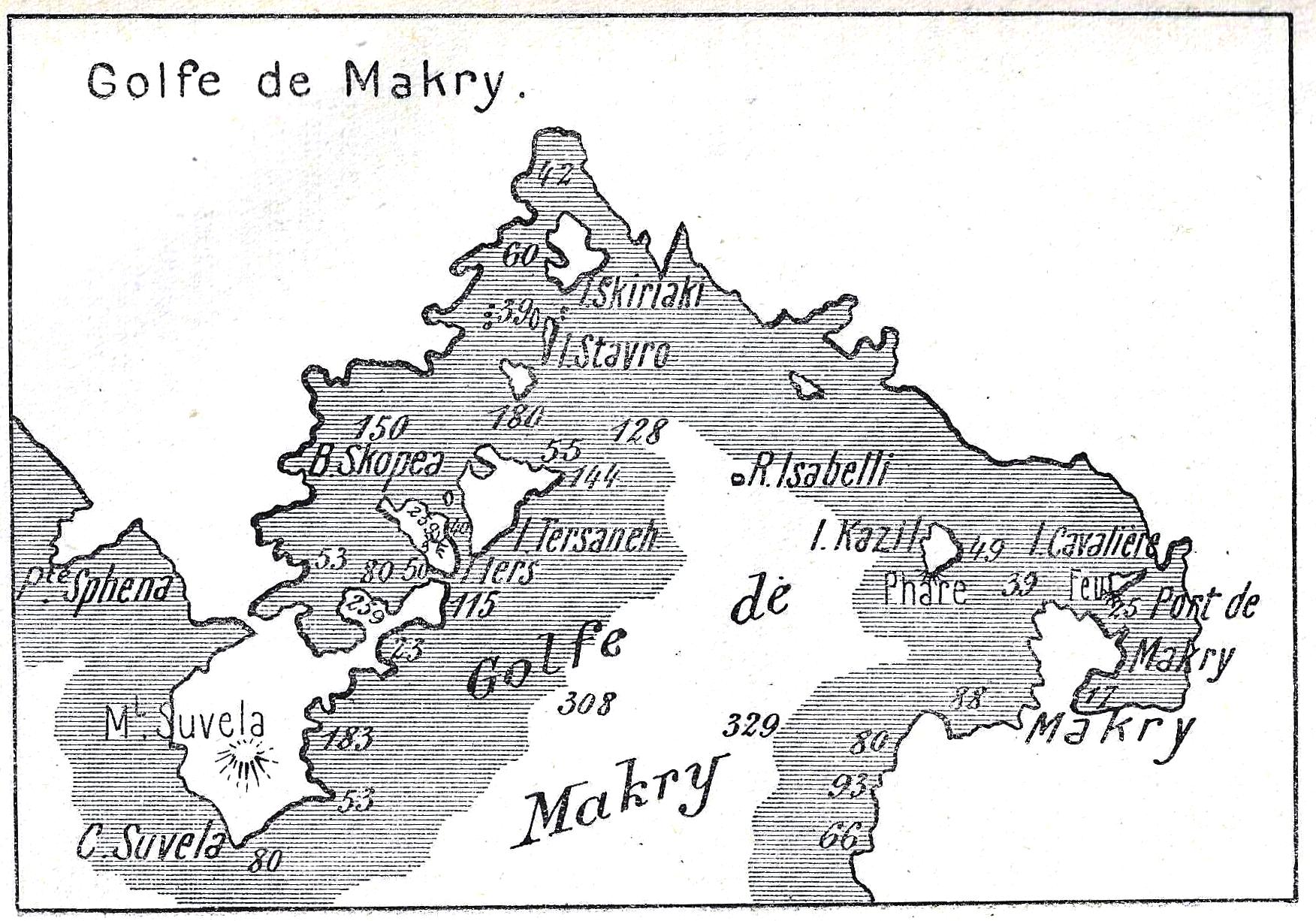

Telandria, Tersaneh, Tersana, modern Tersane Adası [shipyard island], the island has been all these and more.[1] A triangular island with a surface area of about 2.5 square kilometres, lying barely 3 kilometres from the Turkish mainland in the north western corner of the Gulf of Makri [Fethiye]. A bay, sometimes called Shipyard Bay, at the north west corner forms a well protected, but shallow, harbour, which during the early Ottoman Empire is believed to have been used as a ship building and repair harbour.[2]

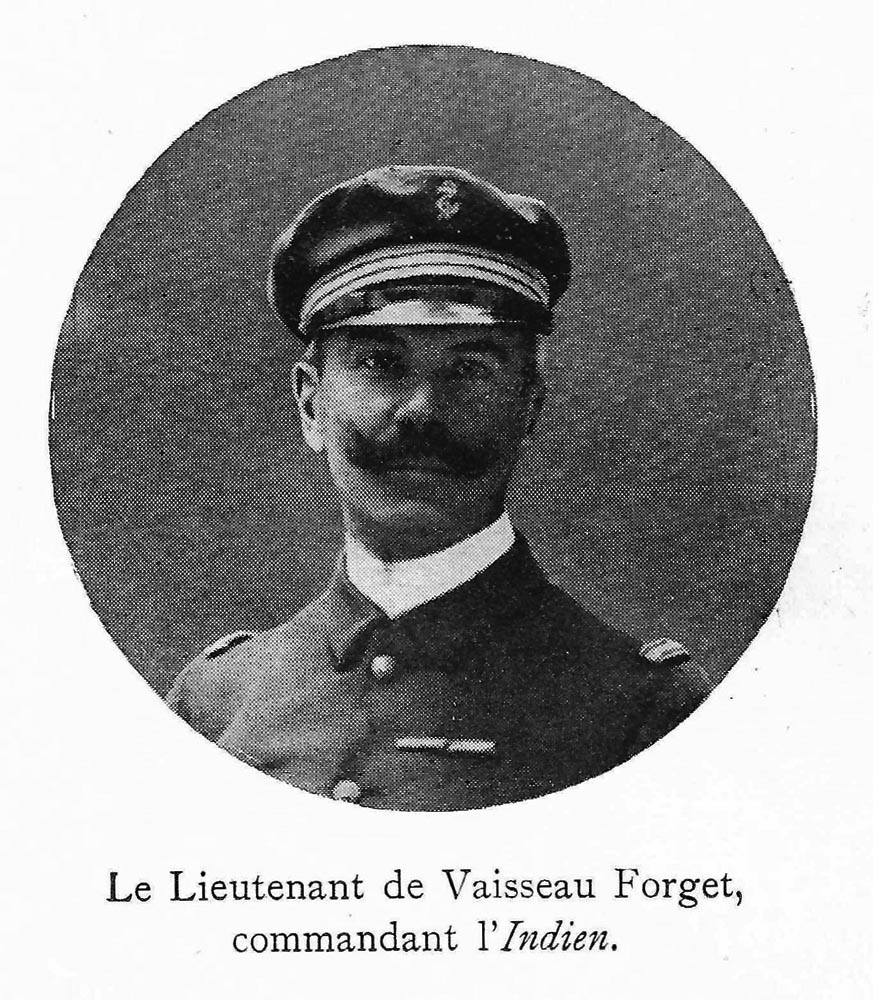

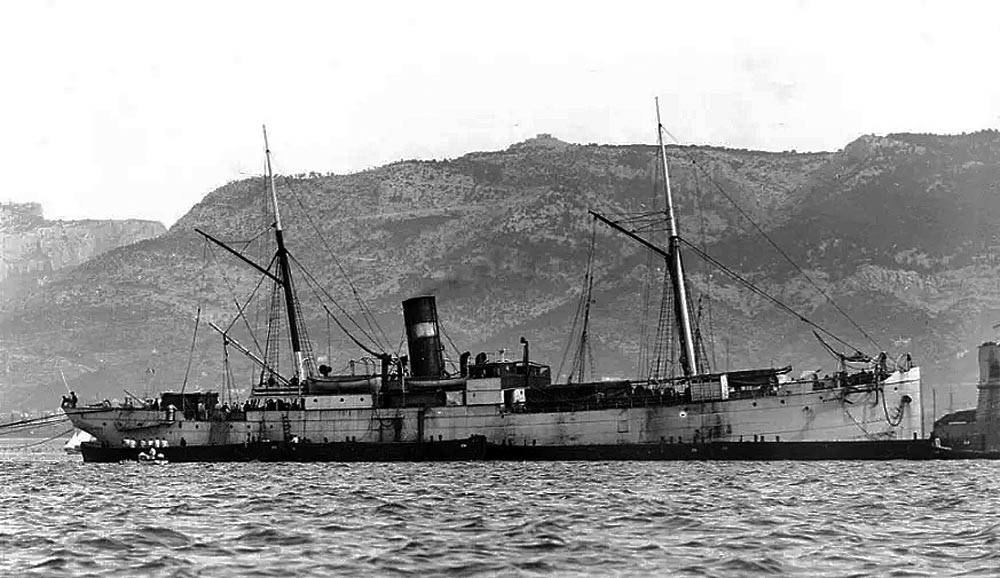

The first French contact with the island appears to have been in early September 1915 when Lieutenant de vaisseau Émile Eugène Forget, commanding the French croiseur auxiliaire Indien, visited the island. Indien had been built at the yard of W. B. Thompson, Dundee, in 1879 as SS Vasco da Gama (1538 grt, 255 feet), 10 knots on a good day. A typical tramp steamer of the period. Bought from her original owners by Soc. Generale de Transports Maritimes a Vapeur, Marseille, in 1883 and renamed Auvergne. Sold again in 1908 to the first of two Greek owners, she was seized, as Indiana, by the armoured cruiser (1892) Latouche-Tréville (capitaine de frégate Charles Henri Dumesnil) at Mersin on 9 April 1915 whilst carrying contraband goods. Taken to Alexandria, renamed Indien, armed with two 65 mm and two 47 mm from the old (1891) pre-dreadnought Jaureguiberry, she sailed the coasts from Tobruk to Mersina, until ordered to Rhodes.

Le Roi des Montagnes

Tiring of the endless Gallipoli campaign, in mid-1915 France sought to increase its presence in the Eastern Mediterranean basin, including the southern Anatolian coast and the coasts of what were then Syria and Palestine. To this end the small Service d'information de la marine au Levant (SIL) in Port Said was expanded. Several small squadrons of armed trawlers and other small vessels were established to watch and search the coastlines to look for blockade runners, smugglers and, increasingly, submarines. One of these squadrons was based at Rhodes to watch the Anatolian coast. The French consul at Rhodes, monsieur A. Laffon, was also involved in intelligence work but reported directly to Quai d’Orsay, sometimes impeding the work of the SIL.

Indien was at Port Said on 28 August 1915 taking on coal and supplies. During the evening Forget received an order from vice-amiral Boué de Lapeyrère, Allied Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean navies, instructing him to proceed to Rhodes there to receive further orders from Capitaine de Vaisseau Frédéric Joseph Moullé (Dehorter, destroyer). Sailing the following day Indien proceeded north to sight Cape Chelidonia [Gelidonya Burnu], located at the western end of the Gulf of Antalya, at 0700, 31 August. Turning west to scout the coast past Castellorizo she arrived at Rhodes at 0900 the following morning.

At Rhodes Forget came under the local command of capitaine de frégate Louis-Hippolyte Violette, commander of the trawler flotilla who, on the evening of 2 September, ordered Forget to take Indien and make a patrol from Marmaris to Cape Chelidonia. Just before sailing the following morning CV Moullé arrived with Dehorter and confirmed these orders. Indien sailed at 0930, 3 September, bound for Marmaris then skirting the coast down toward Cape Suvela, at the southwest entrance to the Gulf of Makri [Fethiye]. Finding nothing of interest, Indien turned into the gulf … well, the rest of this story is best told by LV Forget.[3]

The Suvela peninsula is very rugged; the islets of Iéro [Domuz Adası] and Tersaneh, which extending to the northeast, form a sheltered bay with the mainland. This bay provides all the conditions required to serve as a shelter for submarines. In particular, it is hidden from the open sea; there are excellent small natural harbours, and finally deep water up to 100-150 meters permits diving if necessary.

Steaming around the island of Tersaneh, we arrive at the entrance to Skopea Bay. We study the landscape and memorize the contours of the land, then turn back as if we were afraid to enter this veritable labyrinth. After passing the islands we turn south, moving well out to sea, planning to returning under the cover of darkness to enter Skopea Bay and attempt a surprise attack.

As night falls the Indien is about ten miles offshore, we turn around and set course for the coast. At 2200, we are once again at Cape Suvela. The weather is beautiful, calm, the night is dark and clear, and the stars are shining brightly. For safety, we steer as close as possible to the rocky coastline. We slowly round the northern tip of Tersaneh and enter Skopea Bay, finally coming to a halt at the far end of the bay, southwest of Iéro with our bows pointing north. There is too much water to drop anchor ... Besides, dropping the anchor would create too much noise.

4 September. It is midnight. The weather is beautifully clear. We feel as if we are on a lake, surrounded by wooded hills. Lookouts are posted around the ship as we wait for daybreak, when we can see clearly. Perhaps we will make an exciting discovery, for nothing has revealed the arrival of the Indien in this pirate’s hideaway. At the first light of dawn, the landscape becomes clearer and clearer. Quietly, we set out. Scanning the five or six small coves between Iéro and the Suvela peninsula, we find nothing.

We reach the coast of Tersaneh Island where, at the mouth of the small bay to the north-west of the island, there are two decommissioned schooners moored close to shore. That is all, and there is not the slightest sign of a submarine. We stop for a moment. But lookouts on the island have seen us.

As soon as the sun rises, we see about fifteen boats coming out of a small bay. In the first two men are rowing whilst a third is standing in the bow, rifle in hand. What do these men want from us? If these pirates intend to board us, our guns are ready to fire and eight armed men are on the spar deck ready.

Fifty metres from the ship, our interpreter orders them not to come any closer.

Qui etes-vous? Que voulez-vous?

A conversation begins with the man who appears to be the leader. He calls himself Greek, a friend of the French, and eager to help us in our endeavours against the Turks, his personal enemies.

I immediately see the advantage of making friends with these people. My orders forbid landing any of my crew, but I can utilize local partisans. I allow the leader to board alone, and order the other boats remain stationary.

As the boat approaches, a rope ladder is lowered, and an extraordinary figure appears on the gangway. He is tall and sturdy, wearing a black bandana pushed back on his head, a rifle in his hand, two pistols and a dagger at his belt, a cartridge belt on each side, a bag filled with cartridges is slung across his back, and finally a pair of binoculars slung across his chest. This is, in all his splendour, le Roi des Montagnes himself.

I ask him to lay down his arms. He is not at all pleased with this, but when I explain to him that I am the leader and captain aboard, he obeys and we talk. What I learn is most interesting.

The Roi des Montagnes is called Marko; he is of Greek origin, about 50 years old, and, following a few minor offences, he was imprisoned by the Turks for six to eight years. Currently, he is recognised as the leader of a kind of tribe that lives on Tersaneh, at the far end of the small bay.

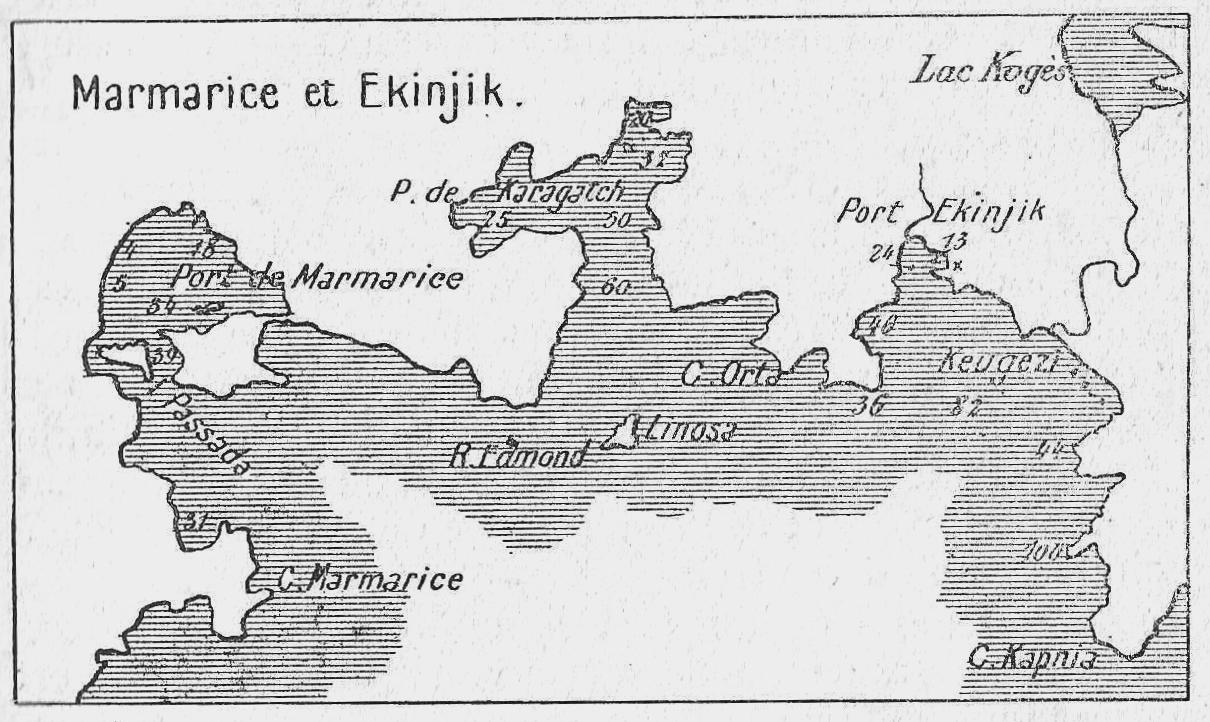

My first question concerns the German submarines. Marko tells me he has seen them in the Gulf of Makry [Makri or, modern, Fethiye], though not in our immediate vicinity. Eight days ago, a submarine entered Port Ekinjik [Ekincik], situated about thirty miles west of the current location of the Indien… Could it still be lurking there? We need to head to Ekinjik without delay.

I invite Marko to accompany me. He accepts with great pleasure, offering to gather 40 armed warriors, much like himself, if I desire. I thank him, saying through the interpreter,

I appreciate your offer to assist me, and I gladly accept it; however, I do not require the 40 warriors you offer. The Indien is a strong ship. If you would like to have a dozen trusted men accompany you, that is acceptable. They can travel in one of your sturdy boats, which I will tow. You will join me on the bridge. To demonstrate my trust, I’ll return your weapons to you. But let me make it clear: I am the one in charge here. It is essential that you and your men understand the importance of following my orders without question.

The Roi des Montagnes, with dignity, insists he is ready to follow my orders. He asks to return to shore to prepare for the expedition with his men, and indicates his desire to leave the next morning. But I won’t settle for that - today is the day, and as soon as possible. I’ll give you until 9 o'clock, that’s the latest. If you’re not here by then, I’ll sail without you. So be it. Marko agrees. Before leaving the ship, he tells me that there is most likely an oil depot in Port Ekinjik. Excellent information. All the Greek boats return to shore with their leader. They are going to discuss things... We are impatient to go west.

At 9 o'clock, as I had ordered, a boat is seen leaving the bay and heading towards us. There are ten men on board, with Marko standing at the bow rifle in hand. We welcome him aboard, and pass a tow rope to the boat. But I notice that they are attaching it to the middle of their boat, I explain that it must be attached to the bow and that they must be very careful when steering. There is some argument between the crew of the boat. So I leave it to Marko, and take care of my ship. But no sooner is the Indien underway, 3 or 4 knots at the most, than cries ring out: the boat capsizes, keel up, throwing the ten men into the water. They clearly didn’t heed my towing instructions.

The Greeks are all clinging to the hull. A boat arrives from shore and picks them up. I ask Marko if, despite the incident, he still wants to come with me. He talks with his men, assures me it is nothing to worry about, and states that a new boat will replace the one that sank.

We set off after reviewing all safety measures to ensure a smooth tow. I increase our speed to 8 knots, and the tow seems to be going well. The weather is beautiful, with a light north-easterly breeze and calm seas as we pass close to the shore. At around 1 p.m., we arrive off Port Ekinjik. The coastline is inviting, with tall, wooded hills framing the area. The port entrance, difficult to spot from the east, appears quite narrow. The Indien heads in slowly.

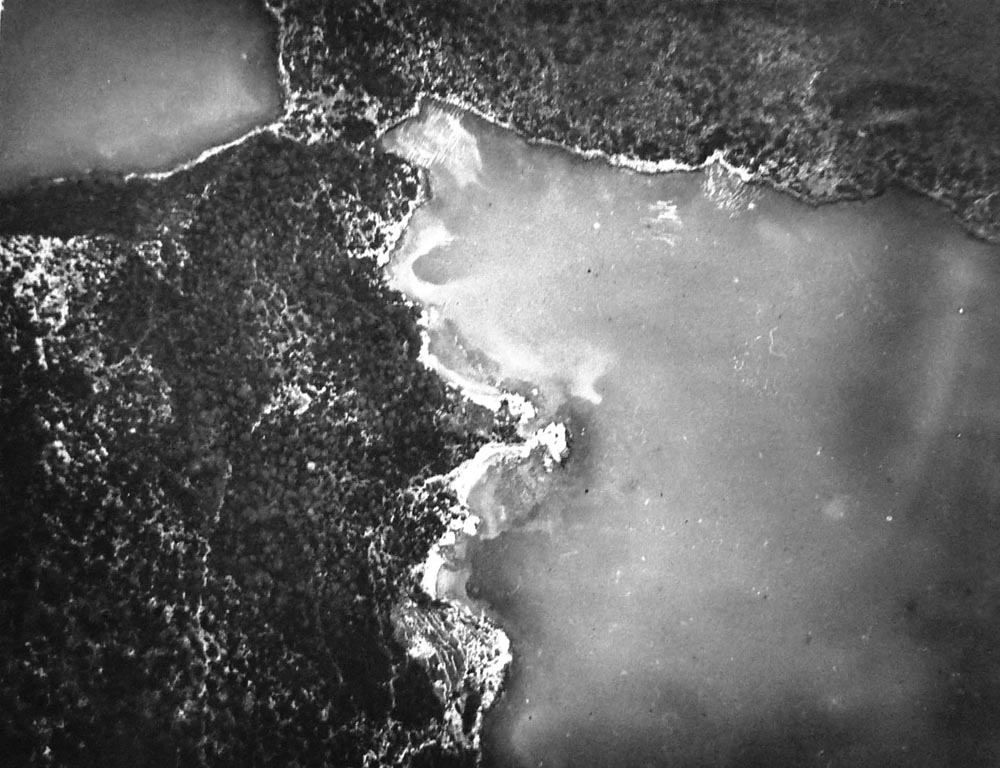

We round a bend, to find a fine natural harbour extending approximately 1,500 metres. All around are hills covered with vegetation, about a hundred metres high. At the end of the bay there is a valley; to the right as we enter, a natural quay from which two small jetties extend and a house further to the right. Marko tells me that, according to his information, the oil depot is located there. But where is the submarine? It has left. The Indien finds itself once again in what feels like a perfectly calm lake. Not a ripple disturbs the surface of the water.

Suddenly, the sound of a horn echoes through the valley. It seems there are people on land, not far from us...

We manoeuvre to turn the bow towards the exit from the bay, I do not drop anchor, wishing to be prepared for any eventuality. I give Marko my orders : Go ashore with his men, go immediately to the house and set it on fire. If there are any guards, bring them aboard the Indien unharmed. Marko and his men push off for the shore and disembark, leaving two men with the boat.

A few minutes later, dense black smoke billows up into the sky, intertwined with fierce red flames emerging from the house. It is the oil … The column of smoke rises high into the sky. No shots were fired. The operation was carried out without difficulty, and I hope to see our new allies very soon.

But suddenly a volley of musketry is heard some hundred meters to the north of the house. The Greeks, as tirailleurs, advance in successive leaps toward the bottom of the valley, skilfully evading fire in a manner as perfect as old soldiers trained in the game of war.

I blow a long whistle to get them to come back, but they continue forward. The horn sounds again, it is a call for help from the guards at the base. If Marko is delayed, it’s probably because he's determined to bring one of those guards back with him.

If there are many armed men, we could find ourselves in serious trouble, potentially caught in a crossfire from hidden snipers in the underbrush and rocks. All crew members are ordered to take cover, just one gun on each side being ready to fire, with its crew ready for action.

The Greeks continue to advance reaching the end of the bay at the head of the valley where the river flows in. Heavy gunfire. Armed men are spotted, retreating inland firing as they go. A few bullets whistle over our heads. The Indien responds with three or four cannon shots.

The boat has followed the partisans in their advance. It is now at the far end of the harbour, near a small beach. The situation shifts rapidly...

Suddenly, oxen appear, chased by the Greeks, who are under fire from the Turks – it is a bull run of a very special kind. One of the oxen rushes into the sea, dragging a Greek desperately clinging to its tail. The Greek throws a rope around its horns and manages to pull it back to shore.

I decide that this farce has gone on long enough, and blow the whistle again to order them to return. We fire a few more cannon shots to cover their retreat and ensure our partisans can safely embark.

Finally, the boat heads towards us. It is heavily laden and drags a large black mass behind it. What is it? The boat slowly approaches, we set up the hoist, with a strap ready to hoist the oxen. There are four of these animals in the boat and two more in tow. One of the latter is bloated like a wineskin, the other has its neck half severed. Quickly, everything is loaded aboard, and the boat taken in tow, and we leave the port without incident, though bullets continue to buzz over our heads.

Marko gives me his report. Next to the stone house was a wooden shack where a large store of oil had been hidden under the floorboards. That is what was set on fire. After setting the fire, the Greeks chased after the armed guards, who had fled to the far end of the bay. While one group dealt with the Turkish soldiers, another successfully captured the cattle.

Returning to Skopea, we keep close to the coast, looking into every nook and cranny. We pass in front of a telegraph line. It is not very far from my Greeks’ hideout, and it must pass through Ekinjik. I tell Marco to send a few men the next day to cut and take away the wires. He promises me he will do so.

It is evident that the ox with the slashed neck is dead, and the one that is swollen like a wineskin has drowned. I give the order that it be tossed overboard, but Marko asks me to give it to him in place of one of the live oxen... Ça va.

We stop in front of our supporters’ hideout, and watch as a rather amusing scene unfolds. Five men surround the swollen ox; two attach ropes to its front legs, pulling it back and forth, another lifts its head while the fourth, armed with a pair of blacksmith's tongs, hooks the animal's tongue and pulls rhythmically, and the fifth brushes its nostrils with a piece of oakum soaked in vinegar... With this treatment, the animal should come back to life.

Sure enough, not long after, Guyomard, our dependable registered nurse, and senior medical officer of the Indien, also occasional servant of gun number 3, climbs onto the gangway, salutes and, with his hand at the height of his cap, reports to me:

Commander, ‘le Beu’ is alive.

Ah!

Yes, commander, he's eating.

I look and see our drowned ox is now upright, standing on all fours and munching on fodder... He has deflated. I have it delivered to Marko, who is delighted, and I give him two more oxen, leaving three left for our use. My men are happy, and so are the Greeks.

Before we part ways, I talk again with the King of the Mountains. He informs me that at the Makri lighthouse, there is more oil guarded by Turkish soldiers, he also suggests in Makri itself we might find something. He volunteers to lead an expedition with his warriors tomorrow. I agree, deciding to spend the night where we are, in front of Marko’s lair. We are perfectly sheltered and safe here.

5 September. 6 o'clock. A boat is heading towards the Indien, Marko once again is standing at the bow, armed to the teeth. He looks quite formidable. I greet him warmly. It is agreed that we will set sail at noon and that, as on the previous day, I will tow his boat with ten men. I remind him once again to strictly follow my orders, and he returns to shore.

Noon. The boat, with its ten men, is taken in tow. The crew now knows the procedure, and nothing untoward happens as we set off. Among these pirates there is a Turkish soldier who has deserted, whom I promise myself I will interrogate.

We set course for the Makri lighthouse, which stands on a small rocky islet named Kizil. We stop at the lighthouse, just fifty metres from a tiny jetty. The Greeks push off for the shore. From the lighthouse, I see three Turkish soldiers in smart uniforms coming out and walking down to the jetty to meet the Greeks. The Greeks and Turks embrace each other, it is most curious. They talk briefly then everyone goes up to the lighthouse.

Half an hour passes, then the Turkish soldiers come out of the lighthouse, each struggling with a large can of oil [or petrol], which they carry to the boat. Then, one by one, the Greeks appear, carrying a variety of items. Several trips are made between the shore and the Indien. A large boat, intended for the lighthouse’s use, is brought on board.

When Marko returns, his mission accomplished, I ask him if he knew the Turkish soldiers, because I am intrigued by the embraces he exchanged with them. He tells me that he did not know them, but that it’s a common practice. He reports that there were found many large oil drums at the lighthouse, in addition to the storage tanks. In accordance with my orders, he emptied the storage tanks. The cans, which held about 60 litres [about 13 Imp. Gallons], were in a small room adjoining the lighthouse. There were a lot of them, which he had carried down to the boat. As for the rest of the haul, it includes a wide variety of tools and the soldiers’ weapons, with a few chickens and rabbits to complete our booty.

The Turkish soldiers present themselves to me, looking quite content. When I question them, I learn that the lighthouse was a supply base for enemy submarines, one of which had appeared four days ago. The Turks cannot give me any details. I keep them on board, naturally, as prisoners.

I summon the Turkish soldier who had deserted, and was now a member of Marko’s band. He knows Makri very well and informs me of a secluded house near the village where Turkish and German officers resided; it is the terminus of numerous telegraph lines. Our captured soldiers confirm this information.

We move deeper into the gulf. In front of the village are moored two large schooners, which appear to be unarmed and light. I send my Greeks, led by their chief, to see what is on board. They return shortly afterwards, telling me that the ships are completely empty. Although tempted to destroy them, I do not do so, to avoid shells falling on the village. My auxiliaries have fulfilled their role. It is now six o'clock in the evening, and I decide to take them back to their base. We head for the hideout.

Out of goodwill, I leave the Greeks a few cans of oil, the large boat taken from the lighthouse, some equipment, and supplies. After bidding farewell to the Roi des Montagnes and his men, we parted amicably. I plan to enlist their help in setting up an intelligence network that can be used to monitor the submarines that are certainly in the region.

The plan will be straightforward. Our knowledge of the coastline between the Kos peninsula and Mersin was extensive, allowing us to identify potential submarine hideouts. From west to east, there is the Gulf of Doris, Marmarice, Port Ekinjik, and Makri. In the immediate vicinity of these bays, two of Marko’s men will keep watch around the clock, ready to light a brush fire if they spot a submarine. The Indien, patrolling the coast day and night, will thus be informed... and will act. The Roi des Montagnes and his men eagerly agreed to this approach. They were tough and disciplined, fully engaged in the game.

After parting ways with my allies, we set out to explore the many inlets along the coast from the Seven Capes [Yediburun] to Kalamaki [Kalkan]. We find nothing.

Completing her searches along the western coast Indien arrived at Castellorizo on 6 September, at this time still nominally under Greek control. Lieutenant de vaisseau Forget conducted ‘amicales’ discussions with ‘notables grecs’ reminding them that a blockade of the Turkish coast was in place. However, ‘From everything that the Greek notables tell me, it is clear that since the beginning of the war a significant amount of traffic has been carried out with the mainland through Castellorizo.’

Forget then returned to Rhodes but, unable to enter the harbour, had to anchor outside the harbour. Shortly after 0615 on 8 September Indien was hit by a single torpedo fired from U34 (Kapitänleutnant ) on its first patrol from Cattaro. The ship sank quickly, taking 13 of her crew with her.[4]

Castellorizo and the Seaplane Carriers

Like Tersana, Castellorizo has had multiple names and its story stretches back into pre-history. It has been fought over and occupied in turn by Hellenistic Greece, Rome, Byzantium, the Knights of St John from Rhodes, Egyptians, Venice and the Ottoman Empire. During the Greek War of Independence (1821-1832) the island was evacuated. Once restored to Ottoman control the population, of largely Greek extraction, quickly returned. Benefiting from a favourable tax situation the island’s merchants created a profitable entrepôt trade in wine, olive oil and timber. Following the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, when the tax breaks were cancelled, the island’s trade and population plummeted. Within four years Castellorizo’s population had halved, largely due to emigration. During the Second Balkan War of 1913 the islanders sought union with Greece. However, Greece was able to provide little assistance merely sending to the island a series of unpopular and ineffective governors. In December 1915 the islanders rose against the current governor, hustled him off the island and established an emergency committee to determine their next move. Into this power vacuum the French moved. On 28 December 1915 they occupied the island, appointing lieutenant de vaisseau Henry Marie Joseph Octave de Bourdoncle de Saint-Salvy as military governor.[5]

Next, HMS Anne,[8] a seaplane carrier of the East Indies and Egypt Seaplane Squadron (EIESS) based at Port Said, visited the island between 21-25 April 1916. The command arrangements on Anne were eccentric to say the least. At this time the ship’s master was Lt John Kerr, RNR; Captain Lewen Weldon, Intelligence Department Cairo, who described himself as ‘a kind of mixture of Liaison, Intelligence and Commanding Officer rolled into one,’[9] looked after general operational control. Whilst on the hatch covers of the aft well deck were two Short 184s, 8004 and 8054. These were maintained by an RNAS detachment with Flt Lt M.E.A. Wright in command and sole pilot, with Lt T.V. Hughes, RFA, and 2Lt A.K. Smith, HLI, as observers. Weldon later recalled,

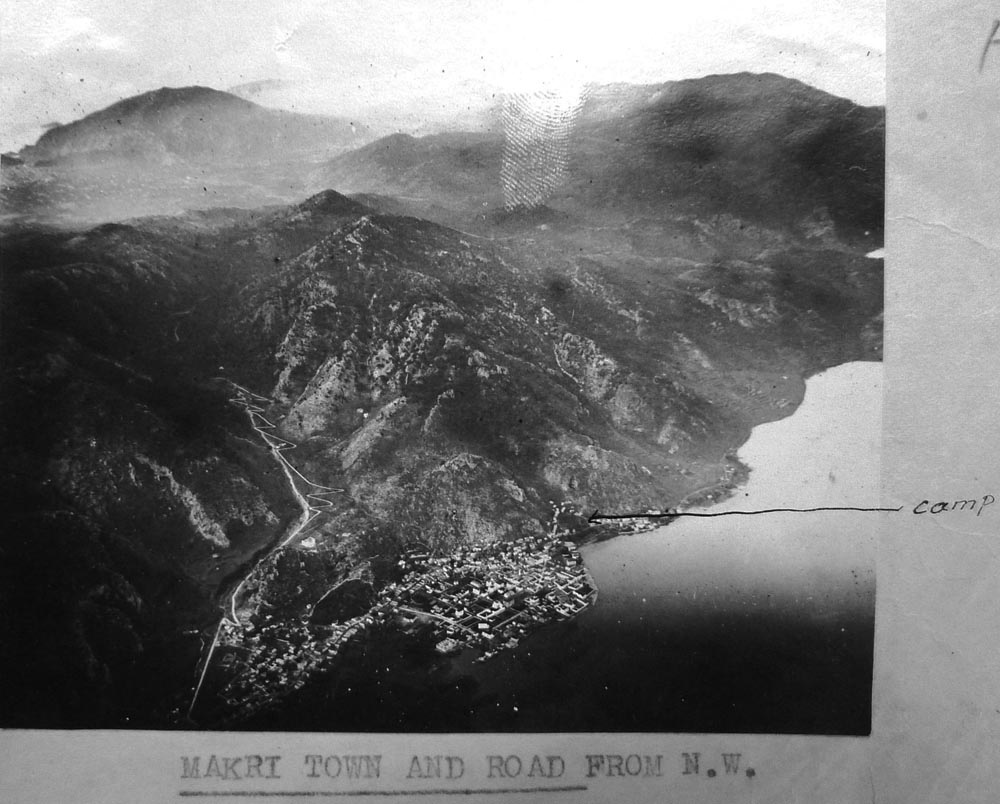

I landed and called on the Governor. He explained that he wanted us to do a flight from there to Makri and Tersana, further west along the coast, and then from the latter place to Marmarice, as he had received a report that a German submarine was making its base near there and had a depot of [diesel] somewhere handy. The idea was to keep the ship concealed in Castellorizo and pay surprise visits to these places by 'plane.

Under the command of Lt Hughes a small party of RNAS mechanics, with cans of petrol, a few spares and some bombs, joined the French armed trawler Nord Caper and set out for Tersana island some 90 km away. They were landed overnight (21/22 April) and settled down to await the Short from Anne. None of Anne’s reports directly mention Marko but at Tersana ‘it was stated on the authority of agents that a submarine had been at the Isthmus at Bogaz’[10] on 21 April.

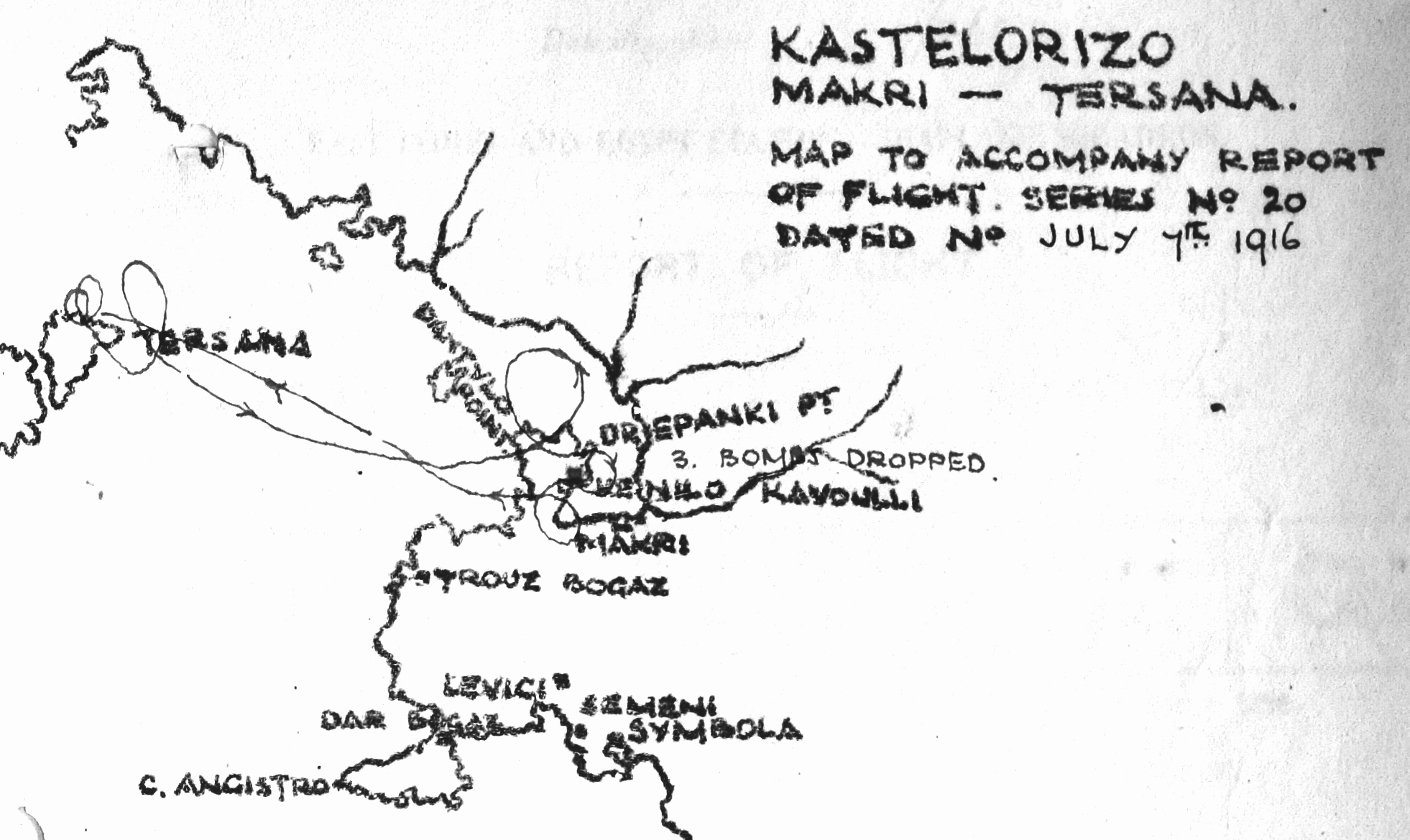

Piloted by Flt Lt Wright with 2Lt Smith as observer, Short 8054, left Anne at 06.32, 22 April.[11] Smith was provided with three 16-lb bombs, a rifle, and a camera. Flying just off the coast they arrived over Makri about an hour later. After carrying out a brief reconnaissance of the area, including Levisi [Kayaköy] and Bogaz, they headed across the bay to land at Tersana at 08.12. At Bogaz, ‘No submarine was seen but the water in the bay to the North of Karazora was covered with a dull bluish film presumed to be a film of petroleum.’ The weather deteriorated and another flight was not possible until the following afternoon. Wright and Smith made an hour long flight around the bay, in poor conditions, checking for indications of submarines, dropping two bombs on some tents outside Makri and reporting another ‘blue oily film’ on the water.

Commencing at 13.09 on 24 April, in improved weather, Wright and Hughes set off further west along the coast to Marmaris. They searched the deeply indented coast line for some 50 km to the north-west, including Ekincik, Karagach and Marmaris for signs of submarines, and also looked for French mines in the passage to Marmaris. There was something at Karagach that was worthy of one of their bombs, the two remaining bombs were dropped on some boats beached near Marmaris. The Short returned to Tersana shortly after 15.00, refuelled and flew on to Castellorizo arriving at 19.00. Nord Caper and the RNAS detachment returned overnight.

Before sailing on the 25th Capt Weldon was asked by Saint-Salvy if they could transport forty-five Turkish prisoners to Port Said. Earlier in January the local militia had raided Antiphilo, bringing back the entire Turkish garrison. Since most food and water for the island now had to be brought in from Rhodes reducing the population by 45 was of great advantage. Anne arrived back at Port Said on 26 April.

The next EIESS seaplane carrier to visit the island was HMS Raven[12] (Lt John Jenkins, RNR, master) between 6-8 July 1916. Raven had sailed from Port Said at 06.30 on 1 July, in company with the French armed tug Laborieux as escort. Flt Lt George Bentley Dacre, was in command of the RNAS contingent, with two additional pilots Flt Lt J C Brooke and FSL W Man, observers Lts J W Brown, RFA, and A P Ravenscroft, RFA, with 2Lt E. King, KOSB. Also aboard were two Short 184s, 8090 and 8091, and single-seaters Sopwith Schneider 3786 and Sopwith Baby 8189. First proceeding up the Palestine coast, where flights were made over El Arish and Haifa, thence to Cyprus with a load of 2680 bags of ship coal for the use of the squadron. Raven next set out for Castellorizo, arriving at daybreak on 6 July. As had Weldon before him, Flt Lt Dacre went ashore to discuss the local situation with Saint-Salvy. Once again he was asked to search the area around Makri, using Tersana as an advance base. This time Laborieux was detailed to carry the RNAS party to the island.[13]

Whilst preparations for the Tersana expedition were proceeding, two local flights were made. At 16.15 Brooke and King set out on Short 8090 to carryout an armed reconnaissance of the adjacent Turkish coast. They first headed east to the local headland of Tugh Burnu then reversed their course over Antiphilo and along the coast to Kalamaki and Volos Island, searching for signs of military activity. They came under rifle fire from two small patrols near Kalamaki, prior to which an overheating engine had forced Brooke to drop their single 112-lb bomb into the sea. No suitable targets were found for the two remaining 16-lb bombs. They landed just outside of the harbour of Castellorizo at 17.47 and were hoisted in twenty minutes later. In the evening, Dacre took out Baby 8189 armed with four 16-lb bombs. Flying east he ‘saw very little but mountains, but dropped my bombs on an outpost which caused a scrub fire. This fire spread rapidly and by night lit up the places for miles. A fine sight indeed and very impressive for the natives of Castelorizo.’

Laborieux sailed at 23.30, July 6, to establish the base at Tersana Island. The tug carried two officers (Lt S J V Fill (engineer) and Lt J W Brown), seven mechanics, a supply of petrol and oil, a selection of engine spares and tools. Offensive ordnance included five 112-lb and 20 16-lb bombs, and a supply of fully loaded hoppers for a Lewis Gun.

Dacre with Ravenscroft as observer on Short 8091 left Castellorizo at 05.15 on 7 July. The Short was loaded with five 16-lb bombs, a Lewis Gun with four hoppers, and a camera. They were to fly along the coast and carry out a reconnaissance on the way to Tersana island. About twenty minutes after starting they saw Man, flying Baby 8189, pass over them on a direct course to the island. Short 8090, with Brooke and King, remained aboard Raven to be available to Saint-Salvy should need arise. There are no reports of any flights being made whilst the Tersana detachment was absent.

The adventures of the Tersana detachment are told by Dacre from his report and diary. Dacre’s flight was not uneventful.

The engine boiled very quickly & I could only get to 500 ft, mountains 3000 ft high went right down to the shore, so I dropped 3 of my bombs into the sea to lighten the machine & flying on got to 1800 ft over Makri district where important recon was to take place. We took photos dropped bombs & got a few rifles fired at us in return, then on & landed at Tersana [at 06.45] where I taxied into the creek. The right hand float touched the bottom before reaching the shore. Beaches being all rocky the machine had to be moored out with the tail on the beach. The engine lost 6 gallons of water. The astonished natives looked on in amazement & offered coffee & more got in the way than any thing in their efforts to assist. The Schneider had not turned up & I was beginning to wonder what had happened to Man when he arrived having struck the wrong Is & found out his mistake. Soon after the French armed Tug Laborieux arrived & we enjoyed a breakfast.

We visited the ‘King & Queen of Tersana’, at his palace. He offered us liqueurs & Turkish Delight which was quite nice. The Queen was about his 15th wife, himself being a desperate pirate who delighted to tell us through our interpreter how he goes out before breakfast & stalks Turks, cutting their throats & heaving them over the cliffs.

By the afternoon the float had taken on water, requiring two hours of pumping to empty it out. At 17.10 Man taxied out with Lt J W Brown as observer, the Short was also carrying three 16-lb bombs, intending to carry out a reconnaissance around the coast of Makri Bay. Before leaving the harbour the engine began to boil then, as water was forced into the float, the Short took on a list with the starboard tip float under water. Man return to shore, but again the Short had to be left on the water.

With Man unable to get off, Dacre took the Baby with three 16-lb bombs, ‘To make a bombing raid on places of importance observed by 8091.’ He took off at 17.18 and was back within twenty minutes. During the flight he saw ‘No tents, camps, men, guns or submarines.’ But he did bomb ‘A concrete patch about 120 feet by 80 feet between Kanillo Kavoulli and Drepanaki Point at the water’s edge. Three bombs were dropped from 2800 feet, one of which was observed to be a direct hit.’ The French intelligence officer later informed Dacre it was ‘being worked on by the Austrians and is well guarded.’ So the assumption was that it was being prepared for a submarine’s use.

Back at Tersana, as it was impossible to beach the Short, the right hand float was hoisted out of the water using the tug’s boat davits. The hope was that it would drain sufficiently overnight to permit a rapid take-off in the morning. ‘This was unsuccessful and the left hand planes were getting under the water with the right hand float out of the water.’ Lacking an efficient pump, or a place to beach the Short, Dacre’s options were limited.

The Short was a nuisance as it was not possible to get it back by flying, there was only rocky beach, so it couldn’t be hauled up & it was dangerous to get the Raven up. I either had to burn it, leave it or take it to bits on the water & get it somehow on to the tug. This was the most feasible. So, at daylight, this was done by strengthening the boat davits & hanging the machine as high as possible, then the right hand planes were removed, floated off and hauled across the Laborieux’s gunwale. Then removing the floats ; after strengthening up the forward davit and hoisting the Short up to the limit of the block ; got many men on to them to sink them clear of the body. The body & left hand planes [presumably folded] were then trussed up to the tug’s side with the tail hauled up out of the water. In this was the Short was brought back to the Raven at Castellorizo, the only damage being a bent elevator and one wing tip float carried away while the Laborieux was rolling on its journey.

Whilst the tug was being loaded, Man was sent off on the Baby to return to Castellorizo carrying a letter for Saint-Salvy. Enroute he dropped three 16-lb bombs on a forested area close to Kalamaki, starting a small fire, then carried on to the island. Landing outside the harbour, at 05.50, Man taxied over the anti-submarine net damaging the tail float. The letter was delivered safely.

Laborieux returned to Castellorizo at 12.45, 8 July, moored alongside Raven and the Short transferred aboard. Dacre presented Saint-Salvy with a reconnaissance report and several photographs. The governor was pleased with the results, commiserating over the damage to the Short. Raven sailed for Port Said at 17.00, arriving three days later. Both Short 8091 and Sopwith 8189 were rebuilt, continuing in service until December 1917 and September 1916 respectively.

Towards the end of 1916, rumours began being reported from the mainland that the Turks were preparing an attack on the island. ‘The Turks, embarrassed by the presence of our two observatories at Castellorizo and Ruad, undertook to drive us out. From the end of 1916, the emissaries who, at the risk of their lives, constantly commute between the islands and the enemy shore, announced the preparation of attacks which the proximity of the mainland makes particularly easy.’[14] Contre-amiral Henri de Spitz, Commandante Division Navale de Syrie, requested another seaplane carrier visit the island to investigate the rumours. The opportunity came early in November.

HMS Ben-my-Chree had spent 3 November in Antalya Bay co-operating with a French bombardment squadron. At the end of the day Ben-my-Chree and Dard (her French escorting destroyer) proceeded to Castellorizo, in response to Amiral Spitz’s request, arriving on the morning of 4 November. Saint-Salvy had no positive information of the whereabouts of the batteries and, after two flights failed to locate them, Ben-my-Chree returned to Port Said.

They were too early. The guns did not arrive until early the New Year. Which, once again, is another story.

The Demise of Marko

Although not much is known about Marko, his full name was Markos Dalaklís.

Lieutenant de vaisseau Forget is perhaps the most informative. So, at the risk of repeating myself, ‘[Marko] is of Greek origin, about 50 years old, and, following a few minor offences, he had a run-in with the Turks, who kept him in prison for 6 to 8 years. Currently, he is recognised as the leader of a kind of tribe that lives on the islet opposite, at the far end of the small bay.’

A more critical view is provided by Kostas Tsalahouris,[15] describing Marko as pirate who,

… has as his “headquarters” the port of Rhodes and the islet of Tersanah, near Makri, and carries out his robberies, from which the Greeks residing on the Asia Minor coast and the mainland suffer most. The persecuted Turks, when the “uninvited guests” leave, then take revenge on the Greeks and snatch from them what they have lost. And all this is done under the pretext of discovering supply depots for the German submarines patrolling the south-eastern Aegean. The tolerance of the Italian authorities for all these actions is obvious. From them they draw military information and what is happening across the sea. In fact, on 5 October [1915], they allow the transfer to the hospital in Rhodes of two Greeks, whom Captain Markos’ men considered spies of the Turks and when they were arrested they hung them upside down on a fire and they suffered terrible burns.

Capitaine de corvette Le Camus, governor of Castellorizo from 18 July 1917 to 14 July 1919, provides some additional information of the French association with Tersana Island.

There were only limited relations between [Tersana] and Castellorizo. The consul at Rhodes [monsieur A. Laffon], who had utilised this island as a base for his operations, named as his chief there a certain captain Marko, the head of a famous gang which was under the surveillance of the Italian police in Symi. The island was visited regularly by French vessels. Marko was killed in an ambush on the Turkish coast, and it was without doubt of little regret to those he administered. A Cretan named Maropakis was named as his successor, but he did not delay in exasperating them by some similar methods of government, without the same vigour, and he was replaced by Foundas, brigadier of police at Castellorizo, with six police officers, and finally all the garrison was evacuated in February 1917. We continued to supply the population which endured some hard times until August 1917. All the population was evacuated by French trawlers to Crete.

As Le Camus mentions above, Marko’s luck finally ran out on 17 July 1916. He was killed whilst on one of his raids by an Ottoman Gendarmerie ambush on the coast. Thus ending one of the more colourful sideshows of the Turkish campaign.

Endnotes

- Place names for this period are quite frankly a nightmare for the historian. The French names are different to the British which in turn are often unrecognisable in Turkish or Greek. Tersana at least is essentially similar in most variations. Modern names are given in [brackets].

- In 1841 British geographer, R Hoskyn, described Tersanah as ‘very fertile, supporting numerous cattle; it abounds also in partridges; being so near the mainland it is much infested by jackals and other wild animals. It is steep and rugged all round; on its summit is a small fertile plain. The tobacco produced here is of superior quality. On the N.E. side of the island is a snug little harbour, and a Greek village surrounded by ruins of the middle ages; and on a hill over the harbour are the ruins of an Hellenic fortress.’ The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 12 (1842), pp. 143-161.

- A translated and edited excerpt from, Contre-Amiral Forget, En Patrouille a La Mer (Payot, Paris, 1929), pp.57-77.

- The French awarded posthumous Médaille Militaire les marins to eleven crew members, but Forget mentions thirteen men missing from a crew of 60 officers and men, also lost were ‘an additional seven prisoners’. A memorial erected at Rhodes contains 13 name plaques, including two not on the list of posthumous Médaille Militaires.

- For a complete and absorbing account of the French occupation see Nicholas G Pappas, Near Eastern Dreams.

- L’escadrille de Port-Saïd was, at this date, part of the EIESS, and the mix of French naval and British army crews was standard procedure.

- AIR 1/665/17/122/722, Campinas Reports, March 1916.

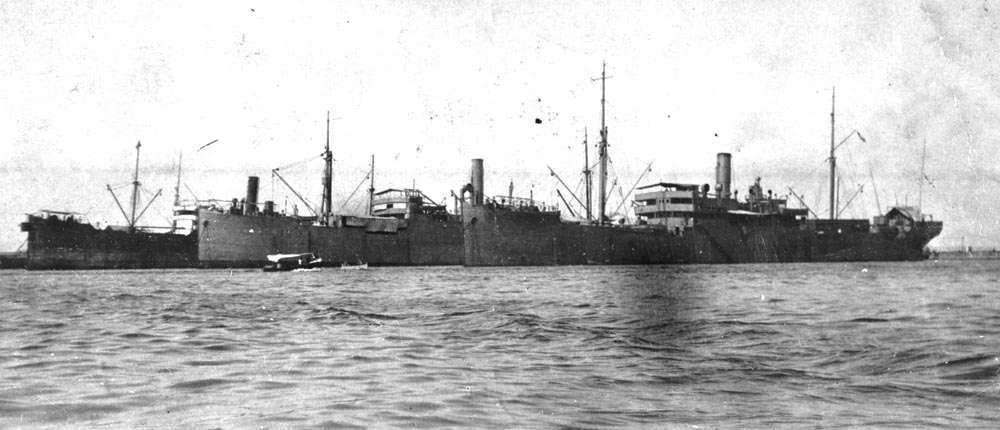

- Anne was an ex-German freighter Aenne Rickmers seized at Port Said in 1914. Owned and operated by Rickmers-Linie, she had been built in 1911 at Bremerhaven in the company’s own shipyard (4083 grt, length 367 feet, 11 knots). In fact a larger version of Indien.

- Captain Lewen B Weldon, Hard Lying (Herbert Jenkins, 1925). Weldon joined the Egyptian Civil Service in 1901, but on the outbreak of was offered a commission in the Dublin Fusiliers, but it is not clear whether he accepted, before being seconded as a Captain to the Intelligence Department in Cairo.

- Dar Boğaz is a narrow pass or bottleneck. On sketch maps produced by the EIESS, Dar Bogaz is shown as a isthmus connecting the Anatolian mainland to the near island penninsula Cape Angistro.

- AIR 1/1708/204/123/73, HMS Anne, Report of Flights, January 1916 to March 1917.

- Raven was another ex-German freighter, Rabenfels, taken at the same time as Anne. Tyne-built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd, Rabenfels was launched in 1903 and owned by DDG Hansa of Bremen (4706 grt, length 394 feet, 10 knots).

- AIR 1/1706/204/123/64, Operation Reports HMS Raven II, April to August 1916; Diary of Lt G.B. Dacre, RNAS, Fleet Air Arm Museum.

- CdV A. Thomazi, La Guerre Navale dans La Méditerranée (Payot, Paris,1929), pp.115/6.

- Published in the newspaper I Rodhiaki (Rhodes’ daily newspaper) on 6 February 2007. My thanks to Nicholas Pappas for translations of Kostas Tsalahouris’ article and, the following, Le Camus’ 1919 Report – Service Historique de la Marine, Vincennes (SHM), SSD-2, Notice sur les événements militaires á Castellorizo au cours de la guerre, 31 March 1919.

About the author

Ian M. Burns is a retired aerospace engineer whose passion is aviation history, particularly early British naval aviation. His latest book is Floatplanes Over The Desert: The Adventures of French & British Naval Airmen Over Sea & Desert Sand 1914-1918. This 568-page study, richly illustrated with photographs and maps, chronicles the operations of the French Navy’s Aéronautique maritime and the British Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean between 1914 and 1918.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles