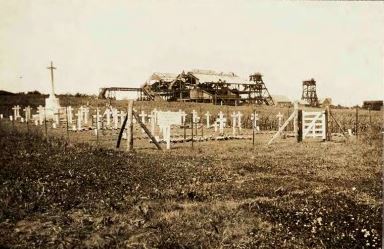

The ‘disappeared’ cemeteries

By the end of the war, the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) faced a monumental task – not only were there an estimated 500,000 ‘missing’ men - many potentially buried in isolated or scattered graves across the battlefields of France and Belgium - but there were also many hundreds of cemeteries, or groups of graves, which had been created during the course of the war. Throughout the conflict, the work of the Graves Registration Commission sought to ensure that war graves were marked with wooden crosses and their location recorded.

The White Cross Touring Atlas of the Western Battlefields was probably the first publication to provide a list of cemeteries to be found in France and Belgium.[1] For many years, it was thought that this Atlas was published around 1920, but it is now believed that it was compiled no later than November 1919. The White Cross Atlas published a road atlas with very detailed maps of the major towns, all trunk routes from the Channel Ports to Paris, a detailed description of the battles, photographs of major towns and a list of war cemeteries. Scattered in this compendium are advertisements on the benefits of their insurance policies and repair networks, together with special policies for marques we still recognise, such as Rolls Royce, Bentley, Fiat, Ford and Renault.

In 1920, His Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO) published a List of Cemeteries in France and Belgium.[2] Also, around the same time, The Pilgrim’s Guide to the Ypres Salient was published, which included a list of cemeteries in the Ypres area.[3]

None of the above sources provide a ‘definitive’ list of cemeteries – but working from these and, in addition, a document which appears to be an earlier version of the HMSO publication,[4] it has been possible to compile a list of all named cemeteries which were included in these publications. This has been further supplemented by concentration information provided on cemetery descriptions on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) website. This has resulted in a spreadsheet with a list of approximately 4,000 cemeteries which included communal/churchyard cemeteries and extensions, in addition to French and German cemeteries.

For the purposes of this article, the list has been refined to include only those cemeteries which could be described as ‘Empire’ cemeteries eg British and Dominion military cemeteries which are no longer in existence. Specifically named French or German Military Cemeteries and Communal Cemeteries/Churchyards have been removed. This approach has been somewhat tested by the concept of ‘mixed’ cemeteries – those that may have been begun by the French or Germans and then taken over by the British. It becomes further complicated as, after exhumation of French or German graves, a cemetery may then have become ‘British’ by virtue of a majority of graves remaining being those of British or Commonwealth soldiers.[5] Over the years since the end of the war, many communal cemeteries and churchyards became ‘disaffected’ and in such instances, CWGC graves were removed.

The above approach produced a spreadsheet of around 1,020 named cemeteries.

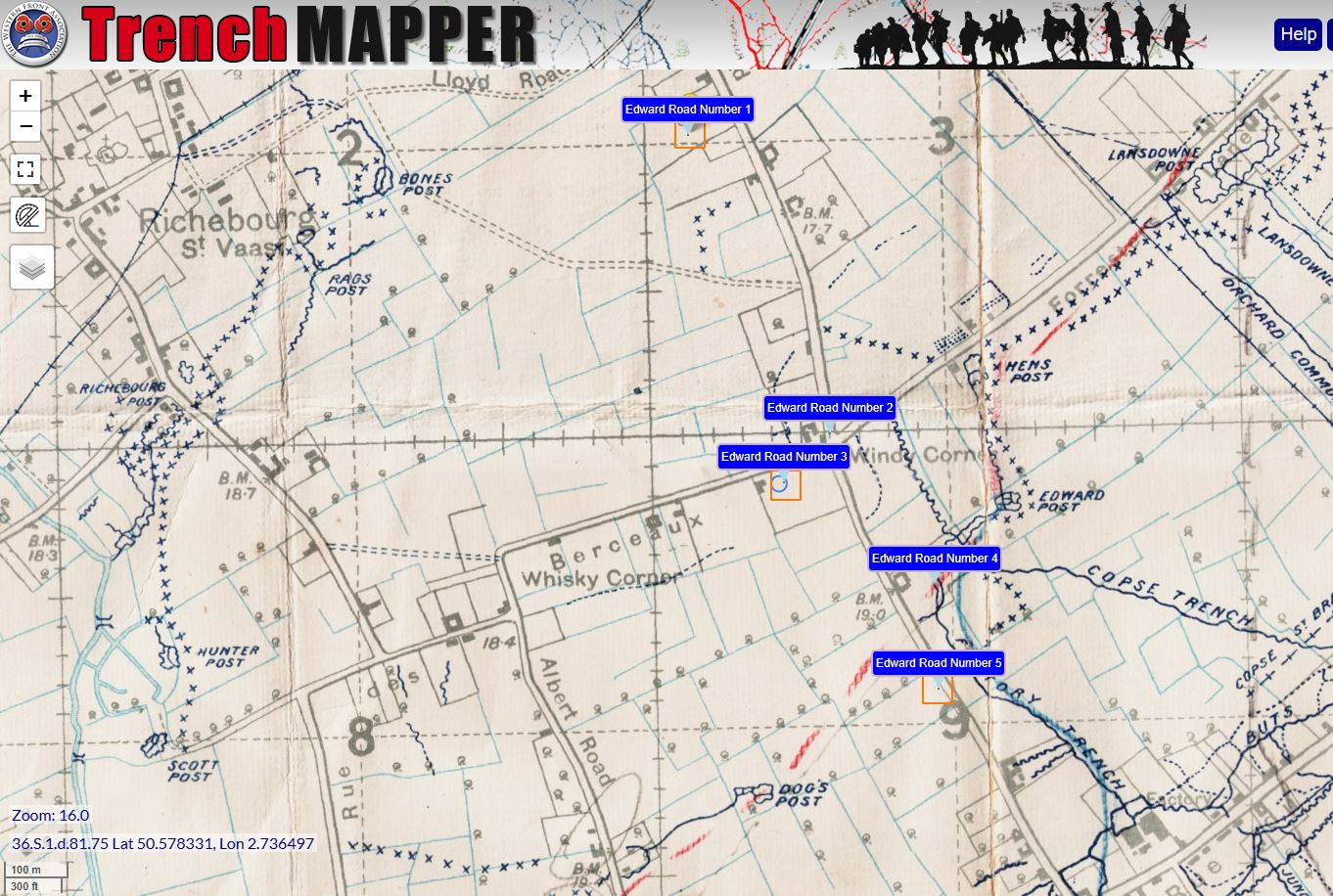

TrenchMapper™

In recent years, advances in web mapping have resulted in widely used applications such as Google satellite imagery and Street View. Specialist websites like The Western Front Association’s TrenchMapper™ use this functionality to offer satellite imagery and Street View plus a trove of over 10,000 georeferenced Great War maps and 50,000 points of interest such as trench names. A small number of IWGC cemeteries have already been loaded and users can search for them, overlay them over a trench map with a date such as 1 July 1916 or run a query to find how many cemeteries lie within 1,000 metres of a location. Many researchers already use TrenchMapper™ to find the original exhumation location for a battlefield casualty.

The TrenchMapper™ team will amalgamate its data with existing CWGC and concentrated cemeteries, so that a TrenchMapper™ user can find a location on the Western Front and ask to view nearby cemeteries. TrenchMapper™ will retrieve every known CWGC / concentrated cemetery or memorial and display it. Only cemeteries in the immediate vicinity will be displayed.

How do we define a ‘cemetery’?

In any of the publications mentioned above, the description of ‘cemetery’ may have been applied to widely varying groups of graves, and indeed there will have been groups of graves with no apparent cemetery name.

A useful categorisation of cemeteries has been provided by Martin Middlebrook:[6]

- battlefield cemeteries where men are buried on the ground where they died in an attack;

- ‘comrades cemeteries’ – often to be found a few hundred yards to the rear of front line trenches;

- Communal Cemeteries, where graves were to be found in French civilian cemeteries;

- Cemeteries around Main Dressing Stations and Casualty Clearing Stations; and

- Cemeteries around large base hospitals.

The names given to ‘battlefield’ and ‘comrades’ cemeteries often reflect immediate landmarks, trenches or regiments. Thus, in the list of cemeteries subsequently concentrated we can see cemeteries named after trenches, farms, buildings or landmarks such as wooded areas. We can also see this in some of the cemeteries which remain –for example, Red House Farm Cemetery, Chili Trench Cemetery, Two Tree Cemetery – but there are many more examples to be found.

The size of the cemeteries subsequently concentrated post-war varies significantly. Using Middlebrook’s categorisation, many were indeed small ‘battlefield’ or ‘comrades’ cemeteries, often with fewer than 40 graves but there are some exceptions which will be discussed below.

The work to identify where these cemeteries were concentrated to has been ongoing for some three years – and is still very much a ‘work in progress’. For this, the work of the late Richard Laughton of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Research Group was a useful starting point.[7] Whilst he had created downloads of concentration documents from CWGC (Concentration of Graves (COG) records) for a number of cemeteries which had received concentrated graves, his focus appeared to be to identify unknown Canadians buried in concentrations. Considerable additional research has been carried out by the author to identify all named cemeteries subsequently concentrated and their destinations.

In many instances, the names of cemeteries from which concentrations were made were detailed on COG records in addition to map references. But there are also many instances where names of cemeteries have been omitted from COG records or indeed COG documentation does not exist. One example is that concentrations in Dernancourt Communal Cemetery Extension are simply marked as ‘exhumations’ on the Grave Registration Forms, with no map references relating to the site of the original exhumation. The details of where these graves were concentrated from– whether from a named cemetery or from the battlefields - is therefore impossible to ascertain. There are also instances where the name of the concentrated cemetery has been omitted from the COG records and there is simply a map reference.

Thus far, there are still around 200+ named British/Dominion cemeteries in the above publications for which no concentration information has yet been found. Of course, many named cemeteries in the White Cross Touring Atlas/HMSO publication still remain in place today.

The Approach to the concentration of cemeteries post war

The IWGC’s initial approach to the task that it faced post war in relation to the multitude of cemeteries appears to have been developed during the war, with a presumption that a group of 40 graves constituting a distinct cemetery was entitled to permanency. This approach would be modified post-war to allow the concentration of ‘less than 40 burials and certain other cemeteries situated in places unsuitable for permanent retention’ as was stated in correspondence from IWGC to a relative in 1920.[8] Indeed, there are only two CWGC cemeteries (excluding French National Cemeteries and Communal Cemeteries and Extensions) with fewer than 40 CWGC graves in either France or Belgium – in Belgium, RE Grave, Railway Wood (12 graves) and in France, Neuville-sous-Montreuil Indian Cemetery (28 graves).

Discussions in 1921 suggest that considerable tensions remained between the policy of the French (favouring larger cemeteries) and the IWGC (favouring the restriction of exhumations ‘to the narrowest limits possible’).[9] The complicated process of land acquisition for cemeteries in France was the responsibility of each Municipal Council in which the land was situated. In 1922, it was identified that there were 17 communes where there were objections to cemetery proposals.[10] A later IWGC file would later refer to ‘blacklisted communes’.[11] In 1923, a Conference took place in St. Omer which specifically addressed the question of land acquisition in these communes – although many of the suggested concentrations of named cemeteries were not carried out.[12]

Another IWGC file identifies that in 1921 there were requests for the removal of six cemeteries in the Commune of Laventie, four of which were in the Rue du Bacquerot, where there were several cemeteries.[13] Some of these requests for concentration related to cemeteries where there were considerable numbers of British graves, notably the Royal Irish Rifles Graveyard where there were more than 800 burials. Of the list of six, five were not concentrated (including the Royal Irish Rifles Graveyard). Nonetheless, in 1925, several newspapers carried stories of exhumations being commenced in Rue du Bacquerot No. 1 Cemetery where there were almost 500 graves and Fauquissart Military Cemetery, with 102 British graves – neither of which were concentrated.[14]

The Commission’s own plans for specific cemeteries could also change, as was the case for L’Homme Mort Cemetery, originally intended for concentration elsewhere, much to the chagrin of Colonel Malcolm, whose son was buried there. At the end of the war, this small cemetery contained only 13 graves. In 1919, Colonel Malcolm appears to have persuaded the Commission that if the cemetery was retained with additional graves being concentrated there, then he would abandon his plans to have his son’s grave exhumed and returned to Scotland.[15]

There are also some examples where the Cross of Sacrifice was erected in cemeteries prior to the final agreement for retention of the cemetery being obtained from the French authorities. This was certainly the case in North Angres British Cemetery and also Caldron Military Cemetery, which were subsequently concentrated to Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery and Loos British Cemetery respectively.

Despite the IWGC’s desire to retain cemeteries and whilst there are many cemeteries with grave numbers ranging from 40 to 100 to be found in both France and Belgium, significant numbers of cemeteries with similar grave numbers were concentrated post war. It is likely that in many of these cases ‘hygiene reasons’ (which could cover a wide range of circumstances including proximity to houses or water supply), difficulty of land acquisition, objections from farmers, problems with accessibility, cost of development etc will all have influenced the decision to carry out exhumations.

The case of Mons British Cemetery is somewhat different. This cemetery had been constructed post war and contained 79 British graves. CWGC records indicate that the cemetery was created in spite of protests from the Burgomeister. It appears that the threat was made that unless the cemetery was removed to the Communal Cemetery, legal action would be taken by the Belgian authorities. The concentration of 79 graves from this cemetery to the Communal Cemetery took place in 1921.[16]

Some examples of larger concentrations

There are several examples of larger cemeteries being concentrated post war.

Blairville Orchard Cemetery contained 360 British graves. Situated in an orchard of a house, completely surrounded by buildings, in 1923 it was recorded that “the French insist on the removal of this cemetery”. It was subsequently concentrated to Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery.[17]

The Dury Hospital Military Cemetery did not appear in the White Cross Touring Atlas or the HMSO List of Cemeteries in France and Belgium, although it was a substantial cemetery containing over 440 graves. There is a clear statement of objections to this cemetery remaining made by the French authorities:

“..situated in the Departmental Lunatic Asylum, right by the side of the Cemetery for the lunatics. It would be dangerous for families coming to pray over the graves of their children or husbands to be in contact with the lunatics. In order to get to the cemetery, it is necessary to go through the Asylum itself. There are dangerous lunatics and war lunatics. They are made to work in order to tire them out. Some of them are at times quiet, but, who all of a sudden, become dangerous. Unfortunate incidents are always to be feared”.[18]

In late 1929/1930, this cemetery was concentrated to Villers Bretonneux Military Cemetery.

More controversy, perhaps, surrounded the concentration of around 450 graves from Rosenberg Chateau in 1930.The problems around this cemetery had been first raised in 1925 due to the family who owned the ruined chateau wishing to have the cemetery relocated.[19] Despite the attempts of the Belgian authorities to broker an agreement with the owner, the Commission reluctantly accepted that removal was inevitable. Unsurprisingly, the matter reached the British press in March 1930 when the graves were concentrated to Berks Cemetery Extension.

In the town of Ypres, there were a number of large cemeteries concentrated with almost 300 graves removed from the Asylum Cemetery and 140 graves from the Ecole Bienfaisance removed to Bedford House Cemetery. The Menin Road North Cemetery (136 graves) was concentrated to Menin Road South Military Cemetery.

V Corps Cemeteries

Approximately 30 battlefield cemeteries were constructed by V Corps after the Battle of the Somme came to a close in mid November 1916 when it fell to this Corps to clear the area of the dead soldiers of both sides.

Whilst a number of the V Corps cemeteries later concentrated were relatively small in size, there is one notable exception – that of the R.N.D. Cemetery (V Corps Cemetery No. 21) which contained 336 graves. This and other larger V Corps cemeteries - Sherwood Cemetery (V Corps Cemetery No. 20) (176 graves) and Y Ravine British Cemetery (V Corps Cemetery No. 18) (140 graves) - were concentrated to Ancre British Cemetery. A number of these V Corps Cemetery concentrations were carried out in the very early post-war period as the original cemeteries do not appear in the HMSO document previously referred to.

One V Corps Cemetery – Ten Tree Alley Cemetery No 1 (V Corps Cemetery No24) was noted on the earlier version of the HMSO publication referred to above as ‘not found’, although CWGC records indicate that it was in fact concentrated to Serre Road No 1 Cemetery. V Corps Cemetery No7 – Ten Tree Alley Cemetery No 2– became the current Ten Tree Alley Cemetery.

There is still further work to be carried out on battlefield cemeteries started by Canadians. These were often not named but given references and numbers – CA, CC, CD. A number of these were concentrated in early 1919 and therefore do not appear in either The White Cross Touring Atlas or the HMSO publications. Of these early concentrations, the receiving cemeteries included Nine Elms Military Cemetery and Bois Carre British Cemetery in the Thelus area.

The destination cemeteries

Many of the cemeteries concentrated after the war were removed to either newly created cemeteries to receive battlefield and small cemetery concentrations, or to existing cemeteries where there was potential for expansion. Some of the latter category cemeterieswould be greatly enlarged post war with exhumations from the surrounding battlefields as well as named cemeteries.

Most receiving cemeteries were deemed ‘closed’ by the mid 1920’s with some notable exceptions eg Serre Road No. 2 remained ‘open’ until 1934. London Road Cemetery Extension and Canadian No 2 Cemetery remained open until the mid-1960’s. For many years, Terlincthun Military Cemetery received concentrations - most notably those in 1964 of 267 graves of British dead from Epernay French Military Cemetery, many of which had been previously concentrated into Epernay from elsewhere in the Champagne region in the 1920’s. More recently, Loos British Cemetery Extension - the second CWGC cemetery to be built since the Second World War - was opened in 2024, with the intention of taking exhumations, mainly now discovered in the course of infrastructure developments.

This means that there is no certainty that a concentrated cemetery would be removed to the nearest IWGC cemetery, although it was the Commission’s intention that reburials would be made as close as possible to the original burial site. Inevitably, there would be instances where there was simply not room to accommodate further burials.

To illustrate this point, there were five cemeteries on Edward Road (numbered 1 to 5) identified in the White Cross Touring Guide in the Richebourg L’Avoue area.

Of these, Nos 1, 3 and 5 were not included in the HMSO Guide published in 1920, suggesting that these cemeteries had been concentrated by then. Nos 1 and 5 were indeed concentrated to Rue des Berceaux Military Cemetery in 1920, whilst No. 3 was concentrated to Guards Cemetery (Windy Corner) (with 5 burials) and Pont du Hem Military Cemetery, La Gorgue in 1920 (7 burials). In 1923, there was a suggestion that No. 2 Edward Road might be moved to No. 4 Edward Road.[20] Both were concentrated in 1925 to Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery, around 13 miles away.

In Belgium, ‘open’ cemeteries included Bedford House Cemetery, Cement House Cemetery and Sanctuary Wood Cemetery. Bedford House Cemetery, the site of Chateau Rosendal also known by the British as Woodcote House, now has four enclosures (No 2, 3, 4 and 6) but Enclosures No 1 – the oldest of the Enclosures - (containing 14 British graves) and No 5 Enclosure (containing 20 graves) were concentrated to White House Cemetery, St, Jean les Ypres and Aeroplane Cemetery, Zillebeke respectively.

An interesting article appeared in the Edinburgh Evening News in May 1928 indicating that two ‘lost’ cemeteries had been uncovered.[21] The first of these, Sanctuary Wood Old British Cemetery was concentrated to Sanctuary Wood cemetery in May 1928, with the second, described as ‘Small Cemetery in Sanctuary Wood’ concentrated in January 1929. Neither had been included in the HMSO or White Cross publications, although Sanctuary Wood Old British Cemetery was included in the Pilgrim’s Guide.

Aisne/Marne areas

In the Aisne/Marne areas where British troops were deployed in the early stages of the war in1914 and from May 1918, many of the British dead were buried in what were mainly French Military cemeteries. After the war, the British graves were removed from most of these with Marfaux British Cemetery and Vailly British Cemetery taking many of the concentrations. As mentioned above, British burials in Epernay French Military Cemetery were concentrated to Terlincthun Military Cemetery in 1964.

Inevitably there were some controversies arising from the immense concentration process that the IWGC faced post war. At the end of the war, Hooge Crater Cemetery contained only 76 graves but was greatly expanded after the Armistice with battlefield and small cemetery exhumations. (The cemetery now contains more than 5,000 burials). After some irregularities were identified in 1920, a Committee of Enquiry was set up by the IWGC. Its report was published in 1921.[22] The irregularities identified occurred at a very early stage of the exhumation process from December 1918 until May 1919 which were carried out by No.68 Labour Company, who had not received any detailed instructions on the identification, recording and reburial process.

A further controversy arose over the work of the Australian Graves Service which is fully documented in a recent article by Peter Hodgkinson published on the Association’s website.

Summary

The work to identify where the ‘disappeared’ cemeteries were concentrated first started some three years ago. The spreadsheet summarising the current known destination of British & Dominion Cemetery concentrations after the war can be found here

The author of this article will warmly welcome any further information that can be provided by WFA members to expand on the research carried out to date. Please use the contact form.

References

- The White Cross Touring Atlas of the Western Battlefields.

- List of Cemeteries in France and Belgium, HMSO 1920

- The Pilgrim’s Guide to The Ypres Salient, 1920

- Sourced through an enquiry to the CWGC

- Consequently, some ‘mixed’ cemeteries may have been omitted from the refined spreadsheet.

- Middlebrook, M & M, The Somme Battlefields pp10-12

- Accessed via The Great War Forum

- CWGC/8/1/4/1/4/37 (HLG18145)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/3 (WG 546/1 PT.2)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/4 (546/2)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/21 (WG 549 PT.3)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/29 (WG 549/4)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/27 (ADD 1/11/4)

- For example, Aberdeen Press and Journal 27 August 1925

- CWGC/8/1/4/1/4/21 (HLG13376)

- CWGC/1/1/5/26 (WG 1294 PT.1

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/29 (WG 549/4)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/22 (WG 549 PT.4)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/18 (WG 546/4)

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/22 (WG 549 PT.4)

- Edinburgh Evening News 31 May 1928

- CWGC/1/1/7/B/48 (DGRE 46)

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles