The first documented case of aerial victory by shooting

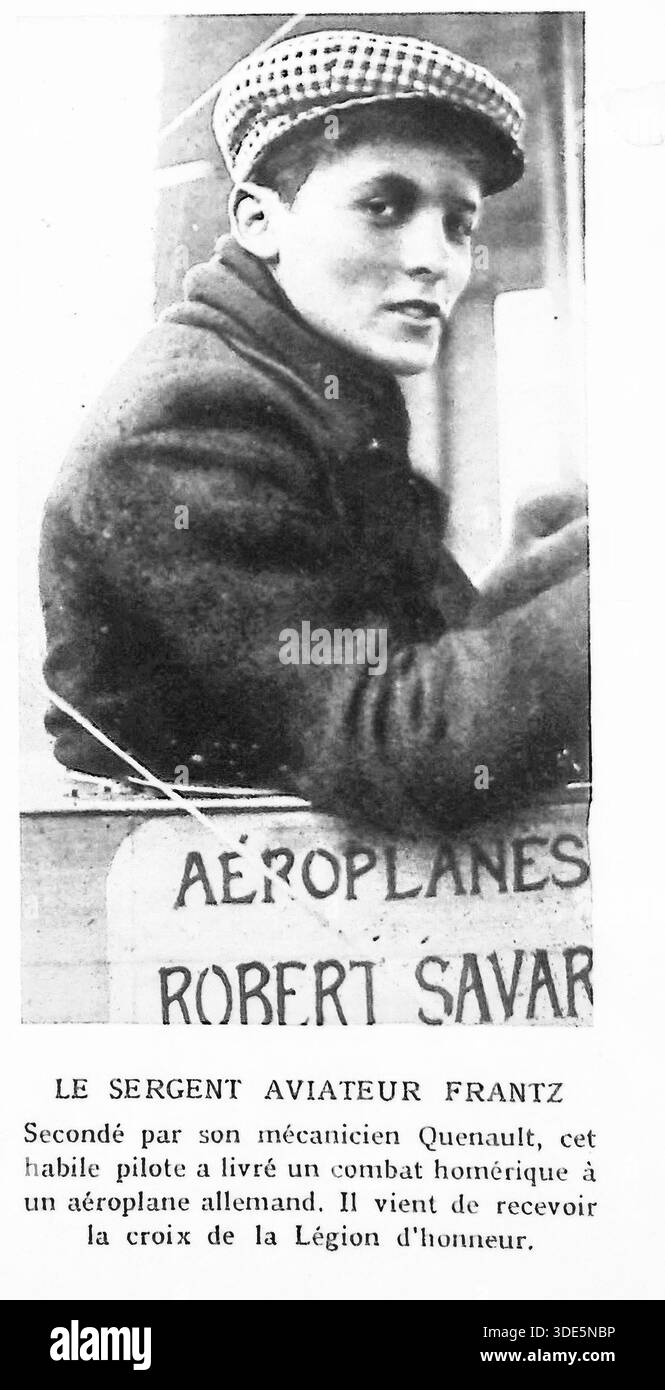

On 5 October 1914 the first aerial combat took place in which one of the protagonists was shot down (as opposed to having been rammed). This took place above Jonchery-sur-Vesle, near Rheims. In this ‘dogfight’ a Voisin III piloted by Sergeant Joseph Frantz and observer/mechanic/gunner Corporal Louis Quénault of Escadrille V 24, encountered a German Aviatik B.II, which was piloted by Feldwebel Wilhelm Schlichting, accompanied by his observer, Oberleutnant Fritz van Zangen, from Feldflieger-Abteilung 18 (FFA 18), a tactical reconnaissance unit.

Frantz and Quénault had already engaged in combat in the air eleven times but had not until this day managed to shoot down their opponent, due to the poor firepower of their revolvers. But they now had the firepower as Frantz had arranged for a Hotchkiss Mle 1914 machine gun to be fitted.

Background

The pilots of both sides were given strict orders that they should carry out their reconnaissance missions and return to base immediately with the intelligence gained, and told that under no circumstances were they to engage in aerial jousts with their opponents, but a number of French pilots took a different attitude. It became the practice of the French observers to arm themselves with cavalry carbines or large calibre revolvers in the hope of taking a pot shot at their adversaries.[1]

French innovation

Captain André Faure, the Commandant of Escadrille 24 (otherwise known as V24 – the V representing the Voisin aircraft flown at the time),[2] belonged to this school of thought and realised that the Voisin aircraft, being a pusher type, would be ideal for mounting a machine gun over the front cockpit. He prevailed upon Gabriel Voisin, the aircraft's designer, to mount a Hotchkiss machine gun on a tripod directly over the pilot's head. The observer / gunner crouched or stood behind the pilot and had an excellent field of fire; six aircraft were armed in this manner.

The opportunity to try out this modification soon arose when a German Aviatik was encountered during a routine patrol by Sgt Franz and Mechanic Quenault.

They opened fire at a range of about 600 metres, but on this occasion the German pilot took evasive action and escaped into a cloud…

5 October 1914

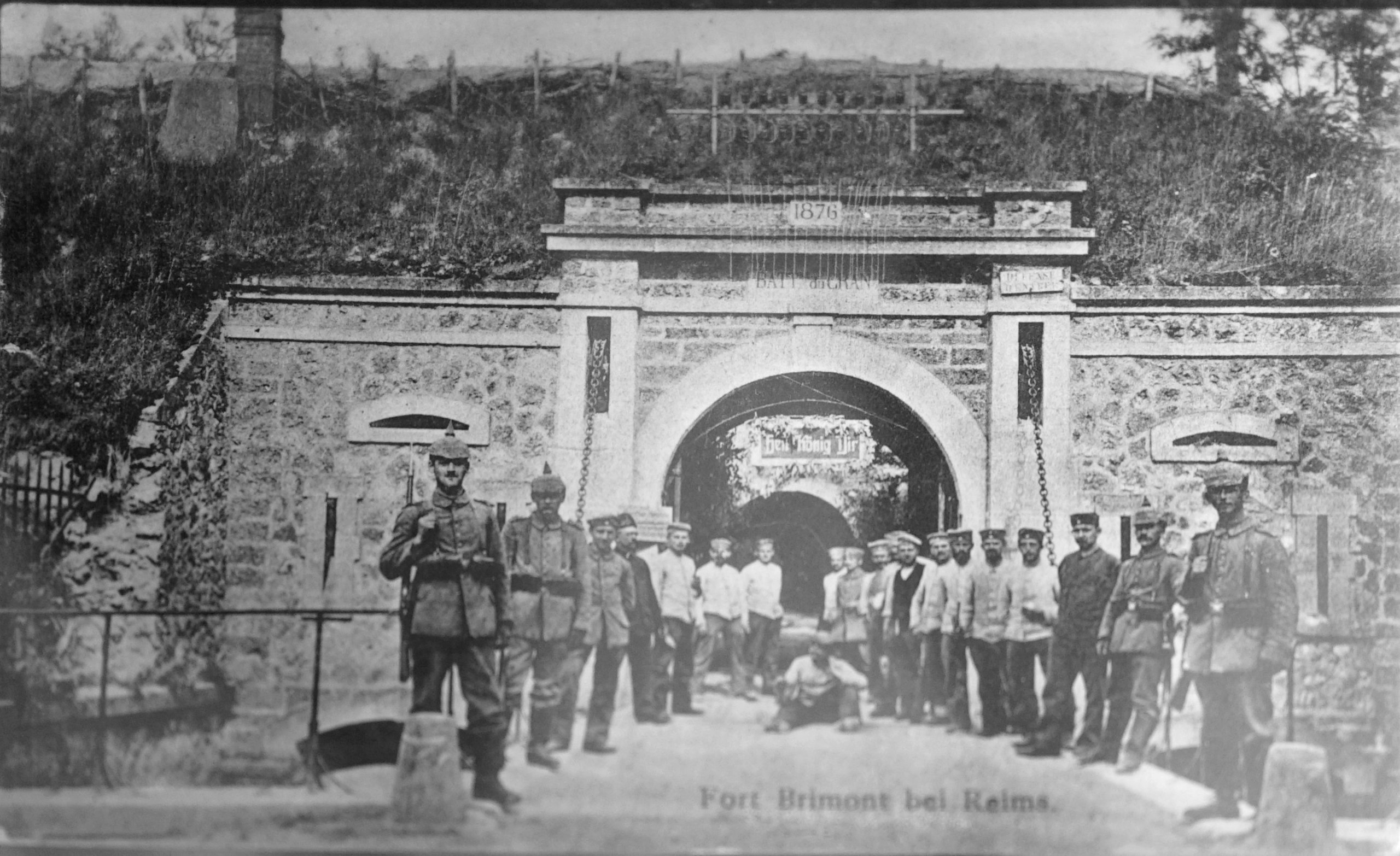

The two Frenchmen took off again on 5 October from their airfield at Lhéry, in their Voisin 3 numbered V89, to carry out a mission in the area of Fort Brimont, which was still in German hands.

Having circled Fort Brimont the Frenchmen headed in a northerly direction and soon observed a large concentration of German troops. Sgt Franz took his machine low over the target while his observer heaved over the side his load of six 90mm shells which had been fitted with vanes.

Not waiting to witness the result they took evasive action to avoid the intense rifle fire from the troops below. It was now 7.30am and, ignoring their orders to return to base when they had completed their mission, they took a long detour to the west over the valley of the Vesle in the hope of another encounter with the enemy.

Meanwhile a German Aviatik biplane, slower than the Voisin and not very manoeuvreable, was taking off from an airfield 20 kilometres north of 32 Rheims. The pilot was Sergeant Wilhelm Schlichting (aged 25) and his observer Lt Fritz van Zangen (31).

In the Aviatik, the pilot sat behind the observer (van Zangen) who had armed himself with a Mauser automatic carbine. His field of fire was limited, he could not fire forward because of the propeller nor backwards because of the pilot, and could in fact only shoot sideways between the wings. They had been fired on by a French aircraft a few days earlier, but had managed to escape into a cloud.

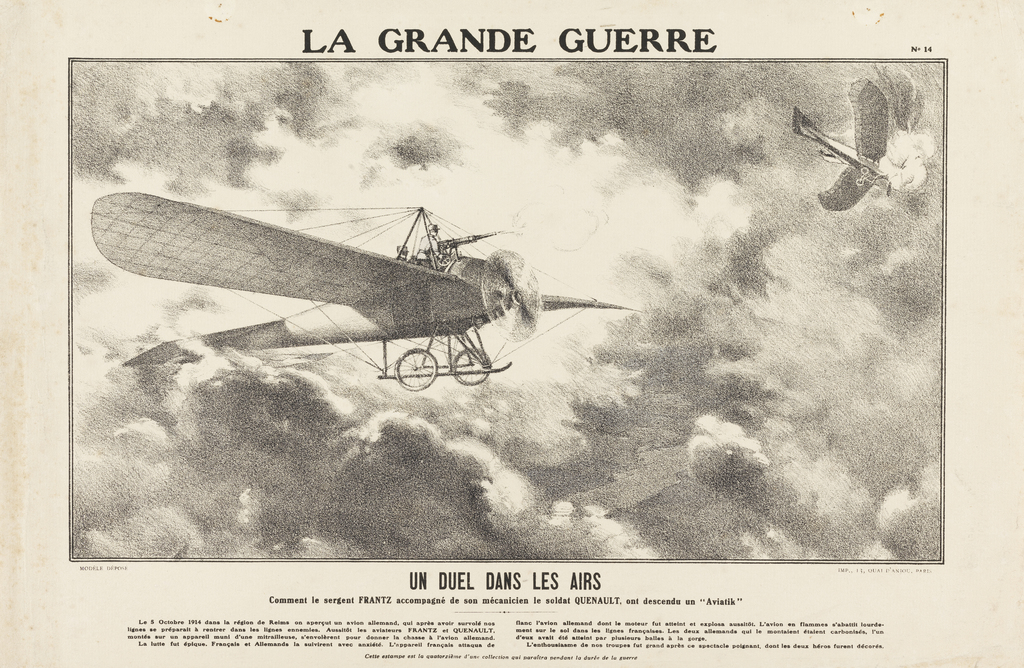

At 8.15 am the Voisin, heading north at an altitude of 2,000 metres, came upon the Aviatik flying roughly 500 metres below and at an angle of 45 degrees to the left. Franz put his machine into a dive at full throttle towards the tail of the German and took up a position to the rear to prevent his adversary opening fire. However, the German pilot was no easy prey and, veering sharply to the left, brought his plane alongside the Voisin, about 50 metres away. Fritz van Zangen opened fire with his Mauser, but had no luck, and soon the Voisin was once again on his tail.

In order to avoid jamming his gun, Quenault began to fire single shots at the German plane which was taking violent evasive action. After 25 rounds it was necessary to change the magazine: no easy task for someone half standing in the cockpit while the planes twisted and turned.

Meanwhile, Franz managed to bring his Voisin to within 20 metres of the rear of his enemy, but after the 47th round had been fired the Hotchkiss seized up. While attempting to free the gun he was astounded to see the Aviatik dive towards the ground before pulling up in a steep climb and turning on its back. Upon righting itself it leveled off and headed erratically over Jonchery in an easterly direction. It then swung suddenly towards the Voisin and Franz's managed to avoid a mid air collision. It became obvious that the German pilot was either dead or badly wounded.

The planes were over the Jonchery marshes when suddenly smoke and flames spurted from the Aviatik, and, in Franz's words, 'It fell to the ground spinning like a large dead leaf'. The German aeroplane crashed in the swamps near the railway line to Fismes at 8.30am. The exact spot is not now known.

French soldiers arrived, and struggling against the intense heat, they pulled the crew clear of the wreckage. The heads and bodies of the unfortunate Germans were intact owing to the swamp water, but their legs were charred beyond recognition.

Franz and Quenault found a suitable field in which to land and they hurried to the scene of the crash. The crowd went wild with shouts and congratulations and the women gave them bunches of wild flowers. In contrast, the two airmen were subdued and silent at the sight of their former enemies, but took some comfort from the knowledge that the Germans would have known nothing during their last horrific moments as each had received at least five lethal bullet wounds.

General Franchet D'Esperey arrived on the scene to congratulate the victors and informed Franz that he would be recommended for the Medaille Militaire, to which he replied as tactfully as possible that he already had one, so the General suggested the Legion D'Honneur.

An unposted letter to his mother found in van Zangen's pocket gave an account of how, a few days earlier, he had been attacked by a French aircraft but had taken evasive action and escaped. We can only wonder whether Franz and Quenault had had a hand in that encounter.

Press coverage

Numerous witnesses observed the event, and the Daily Telegraph, as reprinted in Flight magazine on 16 October 1914, noted that “All the French troops on the spot forgot the danger of passing shells and jumped out of the trenches to watch the fight.”

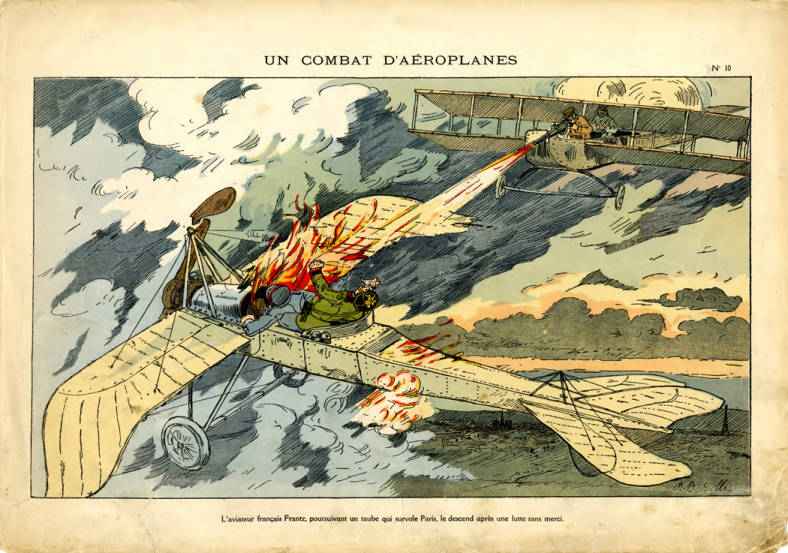

Illustrations of dubious accuracy were produced:

Interview with Frantz

The following account of an interview undertaken in 1976. In this, Joseph Frantz, was interviewed by the Service Historique de l’Armėe de l’Air (French Air Force Historical Service) about his experience.

The interview has recently been made available on the website 'Balloons to Drones'.[3]

Quenault and I had set out, carrying six 90mm shells to drop on enemy troop concentrations. These were difficult to spot at 1,200, 1,500, or 2,000 metres, especially as we had no binoculars.

I was gaining altitude, following the lines between Reims and Craonne, when at approximately 1,800 metres, I saw an aircraft inside French lines heading north. I had, and still do have, despite being 86, quite good eyesight. It was to my left. Focusing intently, I realised it was a German aircraft. It was returning from its reconnaissance mission. At that moment, I was perpendicular to it, slightly ahead and at the same altitude. I alerted Quenault. The first thing I did then was to try and cut off its path by turning sharply to the right. This is where a significant element of luck came into play, as one shouldn’t initiate too early. I was slightly above it, which also helped; it allowed me to dive more or less to catch up before it gained too much distance. This was something I hadn’t managed to do until then. This time, however, I tried to get into a position where I could slow down if needed. It’s always easier to slow down. I arrived precisely where I wanted by diving slightly towards it. I then only had to turn right, position myself in its wake, and it was perfect; everything was in place.

At that point, I was very close. This is the approach that was also used by Fonck, by Navarre, all the great Aces who returned with very few bullets in their aircraft, or none at all if one considers Fonck. As for the sun’s position, I think I might have been well-placed. It was 8:00/8:30 AM; yes, I didn’t realise it. In any case, it was very clear, a cloudless sky. I’m not certain they saw me.

I shouted to my machine gunner to fire. We were so close then that I could clearly distinguish the pilot and the observer. They saw me at the first shot; I saw them turn their heads; I was close. I saw the pilot turn his head back with a surprised look. He was behind. He dipped slightly to gain speed. I followed him like a shadow.

The passenger pulled out a carbine and fired. He had a shoulder-fired carbine, whereas we could aim more easily thanks to the tripod. The German aircraft tried to make right and left turns to break free. The passenger found it difficult to shoot because, as I told you, he was positioned between the pilot and the engine. The pilot, the tail assembly, and the rest formed obstacles, provided I positioned myself exactly in line. We had 25 rounds in the rigid part that held the cartridges. On the 25th, Quenault changed the Hotchkiss belt. The combat was quite long. We fired shot by shot. Quenault fired 47 rounds, which took 10-12 minutes, and by chance, we only jammed on the 47th round. I thought to myself, “We’re screwed again.” Maybe the staff officer is right; we’ll never shoot each other down in the air.

The German pilot was still turning from right to left. He was trying to regain his lines by descending. He descended because we eventually found ourselves at 1,200 metres. And all of a sudden, it pitched up. And, like an aircraft about to perform acrobatics, it remained suspended in the air. Quenault then tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Careful, we’re going to hit it.” We were very close, but when I saw it pitch up, it was slightly to the left. I gave a kick and had already initiated the right turn to avoid colliding with it. It’s true that it would have been too foolish, but in the heat of the moment, one doesn’t think about the danger one might be in.

At that moment, I saw it like an aircraft losing speed. It flipped onto its back, in straight flight, leaving a trail of smoke. It probably had a punctured fuel tank and fuel streaming into the engine. I immediately thought, “I hope they’re both dead… especially the passenger.”

I eventually landed 300 metres from the aircraft wreckage. It had fallen into wooded marshes. I set down in a field a few hundred metres from where our victims were still burning. The marshes were indeed surrounded by suitable landing grounds, fields where there had probably been wheat, and where there was no danger of damage, especially for the Voisin, which had four wheels and wheel brakes. Once again, the aircraft was very advanced for its time.

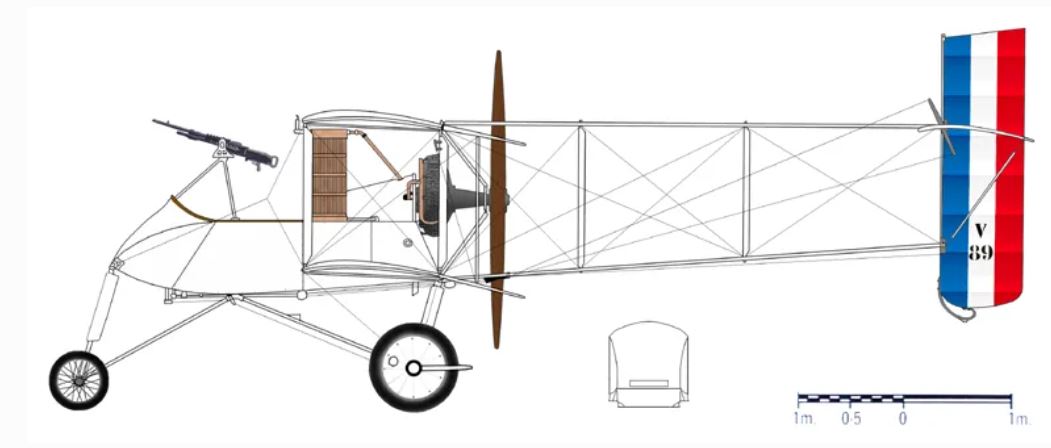

Voisin III - construction and operations

The Voisin III was constructed primarily from steel tubes and canvas, with some wooden components, and powered by a 120-horsepower Salmson M9 water-cooled engine. It was equipped with either a flexible .303″ Lewis machine gun or an 8 mm Hotchkiss M1909 machine gun. The steel tube frame allowed the aircraft to carry a bomb load of up to 150 kg (330 lbs) and was designed with fixed quadricycle landing gear, including an observation window in the nose. Over 850 units were produced in France alone, with additional aircraft manufactured under license in twelve other nations, comprising 400 in Russia, 100 in Italy, 50 in Britain, and smaller quantities in Belgium and Romania.

Gallipoli

It was used by the RNAS in Gallipoli, where it flew out of Tenedos and Imbros. Although it looked ungainly (a cross between a shopping trolley and a pram) it was effective: flown solo and sometimes with an observer, it typically carried a payload of one 100-lb bomb and several 20-lb bombs – Commander Charles Samson (who commanded 3 Squadron RNAS in Gallipoli) even improvised with a home-made petrol bomb.

First combat victory in the Dardanelles

The Voisin also scored probably the first aerial victory of the Gallipoli Campaign on 22 June 1915. Flight Lieutenant Charles Collet and Major R.E.T. Hogg forced down an Albatros B.I near Ali Bey farm (near Achi Baba) after the Turkish aircraft tried to manoeuvre above them to drop a bomb. Hogg fired 30 shots – presumably from a rifle – to ground the enemy, which was subsequently targeted by Allied artillery spotted by a French aircraft.

The Voisin emerged as a standard Allied attack aircraft utilised by various military forces during World War I, including those of Belgium, Italy, Romania, the British Commonwealth, Russia (where many were later deployed by Imperial Russian forces against Bolshevik positions during the Russian Revolution), and Serbia. It served as the principal single-engine Allied bomber in 1915.

After the war Joseph Franz set up a prosperous nickel plating business and continued to pilot an aircraft up to his 80th birthday.

He inaugurated schemes to assist young pilots and formed the association of wartime flyers 'Les Vielles Tiges'. He died in 1979 at the age of 90, outliving his great friend Louis Quenault.

The German pilot, Wilhelm Schlichting and the observer, Fritz van Zangen are buried in the military cemetery in Loivre.

Memorial

A centenary ceremony was held on 5 October 2014 in Jonchery-sur-Vesle during which a commemorative plaque was installed in the presence of the descendants of Joseph Frantz. An art work commemorating the events of 5 October can be seen in the village of Muizon, close to Jonchery

References

[1] The description of the combat was originally published in Gunfire which can be accessed by WFA members in the Searchable Magazine Archive. This account appeared in Gunfire 30, pages 31-35.

[2] French squadrons were typically designated by their principal aircraft type, whereas RFC squadrons were identified by number alone. Early in the war, British squadrons operated a mix of aircraft types but by 1916 squadrons began to specialise by role and equipment. The French system meant designations reflected the main aircraft type from the outset. The French squadron at Gallipoli was MF 98 T: MF for Maurice Farman, 98 the squadron number, and T for Tenedos (the base). When that squadron later received Morane scouts, the original designation remained unchanged.

[3] www.balloonstodrones.com/2026/02/05/interview-sergeant-joseph-frantz-the-first-aerial-combat-victory/

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles