An Unintentional War Heroine by Joyce H. Munro

- Home

- World War I Articles

- An Unintentional War Heroine by Joyce H. Munro

With her long auburn hair pinned up in loose curls, her coy smile and delicate beauty, Alice Elizabeth Thomson (1861-1920) was a luminary of Toronto society at the turn of the century. She and her sisters belonged to several ladies clubs and they were “at home” on Mondays to receive guests at 152 Bloor Street East. Given her good looks and high spirits, plus a substantial inheritance from her father (1), she led a very pleasant life.

However, we will come to learn that Alice made a decision to give up her social standing in order to help others, influenced no doubt by the Thomson’s Scots Baptist heritage. Many single women of that era were “called” to do volunteer work, but what makes Alice’s story intriguing is where and who she helped.

We know little of Alice’s childhood. She was born in Montréal and lived there until age fifteen. Unfortunately, details of her schooling and her friendships, as well as the record of her birth, have vanished. The only clues come from photographs taken by William Notman of a startle-eyed toddler nervously fingering her tartan sash and another photograph the next year of a more confident child with shy gaze and slight smile, holding onto the skirt of older sister Kate (Catherine Sinclair Thomson, 1856-1926). Notman photographed the Thomson family several times during the 1860s—an indication of their standing in Montréal.

We learn of Alice at age thirty-four through the eyes of her nephew, from a journal he kept of their trip abroad in 1895. Kenneth William Reikie (1881-1972) and his family took Alice with them to England and from there she went on to Switzerland to visit her oldest sister, Mary Ker Thomson Way (1842-1926). To young Kenneth, Auntie Alice was a good trouper who recovered quickly from sea sickness on the voyage over and went along on marathon sightseeing tours to just about every place open to the public in London. He referred to Alice and his brother, 19-year-old Tom (Thomas Thomson Reikie, 1876-1967), as “the red-headed pair.” In another passage, he called Alice “Auntie Babba.”

At the turn of the century, we get another peek at Alice, sprawled leisurely on the ground at her mother’s feet in the side yard of their Bloor Street home. Her dress is lace-embellished, her hair tousled and the expression on her face confirms that this is a vivacious woman to be reckoned with. Other glimpses of Alice come from formal photographs taken in Lausanne when she visited Mary and her husband, artist Charles Jones Way (1834-1919)—and from her Bible.

Despite her reputation as “kind and bright and strong,” Alice wrote notes in her Bible that indicate she was struggling with what to do with her life and even to age fifty, her struggle continued. In her search for a way to help others, Alice pursued membership in the Salvation Army, according to one family story. Although she never followed through, she remained close to the Army leaders in Toronto; one summer loaning them her vacation home at Pointe au Baril.

Alice was an admirer of James Hudson Taylor (1832-1905), a British missionary and founder of the China Inland Mission (CIM). She and her sister Anne Jane Thomson (1845-1927) likely attended meetings when Taylor was in Canada raising support for the mission. In the margins of her Bible Alice would write the name “Hudson Taylor” or initials “JHT” and the date she heard him preach from a passage of Scripture. She may have been in the throng of young people who heard his appeal for new missionaries in Toronto in 1888 and paraded with him and his new recruits down Yonge Street to the train station as they set off for Shanghai.

Although Alice did not volunteer to go to China as a missionary, she stayed connected with the Taylors and her family contributed to the mission. Then in 1900, the Taylors retired to Switzerland and one Christmas they met Alice and Anne Jane for afternoon tea in a town near Interlaken. A postcard sent to their nephew Tom in Toronto describes the occasion:

Dr. and Mrs. Taylor met us at Spiez on our way here and we had an hour together and a cup of afternoon tea—he is such a dear man—such a sweet spiritual face—but he is almost stone deaf now, also very poor & with barely enough for their daily wants. Yet the peace on his face!

Clearly Alice held J. Hudson Taylor in high esteem. In fact, she was with the Taylors at their pension in Les Chevalleyres when Hudson’s wife died in 1904. And Alice stayed on to care for Taylor that year. Had it not been for Alice, J. Hudson Taylor might not have regained sufficient strength to make his eleventh trip to China at the start of 1905. It was Alice who prodded him to get more exercise, against the wishes of Taylor’s niece, Mary Louise Broomhall (1865-1944) who was also staying at the pension.

Exercise turned out to be a good thing and with the assistance of Alice and his niece, J. Hudson Taylor regained his strength and in February 1905, started on his final trip to China. Alice returned home to Toronto and began volunteering at the CIM mission house. When she received word of Taylor’s death in China, she consoled herself with a chapter from the Psalms and wrote in the margin: J.H.T. June 3, 1905.

Over the next two years Alice continued her work at the mission house and occasionally traveled to the CIM mission house in Philadelphia. But she was drawn back to Switzerland again and again. Then came her trip in 1916 when everything changed—Alice and her sister Anne Jane found themselves hemmed in by the war.

Instead of returning to Toronto, they bid their sister Mary goodbye in Lausanne and went east by train to Château-d'Oex, nestled at the foot of the Vanil Carré mountain. When they saw the shortage of food and living conditions for British Commonwealth soldiers interned in the village, they stopped being tourists and started working. By 1917, there were 600 soldiers living in hotels and chalets in Château-d'Oex whose only task was recuperation. Alice and Anne Jane remained in the village until peace was signed, working alongside the Swiss Red Cross. After visits with family and friends back in Lausanne and Chexbres, they started off for Italy but were forced to stop at Vevey. Alice was ill and needed a doctor’s care. She may have contracted influenza or simply worn herself out and despite her “strong constitution,” she never recovered. Alice died July 12, 1920 at L'hôpital du Samaritain. In Toronto, a newspaper columnist wrote of her:

“LAST POST” SOUNDS FOR ONE MORE CANADIAN WAR HEROINE.

“She will truly be numbered among the war heroines who gave their lives for others.”

This was a soldier’s tribute at the news of the death in Vevey, Switzerland, of Miss Alice Thomson. Her brother, Mr. T.C. Thomson, of this city, has just received the news by cable.

Her death has come as a great shock to her many friends here. Wonderful letters from overseas had told of her great work for poor soldiers, refugees and prisoners. Caught in Switzerland when war began, Miss Thomson and her sister took a small chalet, not far from the border and kept it open every day for rest and refreshment for the war sufferers.

Despite the great food scarcity, Miss Thomson managed to find it for the distressed who came to her. Then, though the end of the war left her constitution much undermined by her continuous devotion to her work, Miss Thomson was unsatisfied. She was about to begin relief work in Italy when her sudden death occurred.

In traveling back and forth across the Atlantic, first to care for Dr. Taylor, then to care for interned soldiers during the war, it seems that Alice had figured out what to do with her life. Her Bible gives us a final clue. On February 27, 1918 she noted the date in the margin of the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 1, next to the story of another woman who was struggling with what would become of her life. The chapter includes a hymn, often referred to as the Magnificat or Song of Mary. In tribute to God her savior, Mary says: He hath filled the hungry with good things.

Quite literally, this was what Alice wanted to do—fill the hungry with good things. And for this, she willingly laid aside her status in Toronto society.

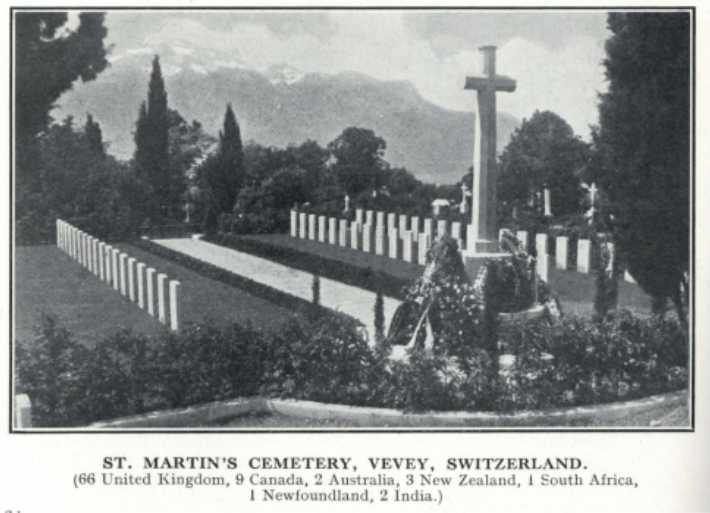

On a hill high above Lac Léman is a grassy courtyard bordered by close-clipped hedges and traversed by a wide stone walk front to back. In the center of this park-like setting stands a cross—the Great Cross of Sacrifice—on which is mounted a bronze sword pointing downward. On either side of the walk are rows of headstones, all the same shape and size. This is Cimetière Britanique at L'église réformée Saint-Martin in Vevey, the final resting place of eighty-eight British Commonwealth soldiers and airmen who died in Switzerland and near them, a civilian, Alice Elizabeth Thomson.

Article y by Joyce H. Munro

Resources:

“This Life of Mortal Breath,” CrossCurrents, Volume 65, Issue 4, December 2015, pp. 476-484.

1916-1918: Prisoners of War Interned in Switzerland at https://interned-in-switzerland-1916.ch/

Switzerland and the First World War at http://www.switzerland1914-1918.net/

The British Interned in Switzerland at https://archive.org/details/britishinternedi00pico

Footnotes:

1) Thomas McLerie Thomson (1813-1889) and brothers were partners with their father James in Thomson & Sons, a general merchandise store established in La Prairie, Québec in 1823. As business expanded, T.M. Thomson opened stores in Napierville, then Lanark and Perth, Ontario. By 1851, Thomson had moved to Montréal to enter the wholesale dry goods business with James P. Clark, and later with J. Thomas Claxton. In 1866, Thomson sold out to Claxton for $200,000.

2) James Thomson and family were members of the Baptist church in Paisley, Scotland. After immigrating to Canada, he and his sons were instrumental in establishing the Baptist church in Perth, Ontario, the Canada Baptist Missionary Society, the First Baptist Church of Montréal and the Canada Baptist College.

3) “Missie A. E. Thomson,” Montréal, QC, 1863; William Notman (1826-1891) I-8943.1 and “Misses K. and A. Thomson,” Montréal, QC, 1864; William Notman (1826-1891) I-10999.1 at the McCord Museum, Montréal.

4) Passages from Kenneth William Reikie’s journal are reproduced in Reikie-Dobbyn Family History, published privately in 2002.4)

5) L to R: Elizabeth Anna Sinclair Thomson (mother), Alice (seated on ground), Catherine Sinclair Thomson (sister), Mary Ker Thomson Way (sister), Burns Ker Weld Thomson (nephew), Anne Jane Thomson (sister). From the Thomson family photograph collection with the author.

6) Alice’s Bible is with the author’s family.

7) Postcard does not have date or stamp, probably 1900-1903; with a Thomson descendent in Montréal West.

8) Alice is named in an article by J.S. Helmer recounting Jennie Taylor’s last days in China’s Millions, North American Edition, 1905, p. 86.

9) Letter dated 1916 sent by Mary Ker Thomson Way to her sister-in-law in Toronto, tells of Alice and Annie’s whereabouts in Lausanne, Château-d'Oex and Vevey. Letter is with a Thomson descendent in Toronto.

10) Immigration records of Alice and Anne Jane were obtained at the Archives de Vevey in 2009.

11) Alice’s obituary appeared in the Toronto Telegram in 1920, written by Lucy Doyle (byline Cornelia), editor of the women’s page. The obituary was reprinted on cards and given to her family for distribution. Cards are with a Thomson descendent in Toronto.

12) Luke 1:53, The Holy Bible, King James version.

13) After 1925, the annual concession fee for Alice’s grave was no longer paid. Her grave was reused fifty years after her death.