An American in the British Forces: The story of Owen Cobb Holleran and his war

- Home

- World War I Articles

- An American in the British Forces: The story of Owen Cobb Holleran and his war

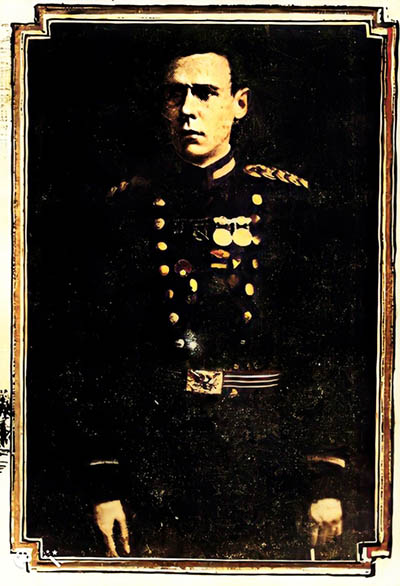

Born in 1892 in Atlanta Georgia in the United States, Owen’s father, was Irish and his mother American. Owen was employed as a clerk in the Southern Bell Telephone Company in New York, and he was a lieutenant in the Georgia Regiment of the National Guard. In 1915 Owen and his close friend Iver Meredith Gray were determined to be part of what seemed like a great adventure – the European war – but at the time the USA was not involved and had introduced the Neutrality Act in 1914. Even more serious, an American swearing allegiance to a foreign country could be punished with the loss of citizenship.

This was no deterrent and they tried to enlist in the British Army at the New York Consul, but as American citizens they were turned down. Even more determined to enjoy an adventure together, they managed to find a ship, the SS Manhattan, which was sailing for England the following day. Another young man, Albert S Mathieu claimed to have travelled with them. Having little money, they needed to work their passage. The Crew list revealed:

“Meredith Gray age 28, place of birth North Carolina, Horseman”

“C Halleran age 23, place of birth Atlanta Georgia Horseman”

Reaching London the two close friends enlisted, according to Holleran’s diary, at an office in Scotland Yard. (Matheiu was never mentioned.) When asked which service he preferred he told the recruiting office: “No choice, just as soon serve in one branch as the other. My only request is that you send me somewhere hot”

They were both assigned to the 6th Dublin Fusiliers as privates, and sent to Victoria Barracks in Cork for training and both volunteered for service in the Middle East. Holleran’s number was 20105, Gray’s 20206.They must have done well, as they were both offered a commission.

Sailing from Dublin to Holyhead in a crowded and uncomfortable ship, they eventually reached Southampton. The next leg of the journey was in the Allen Liner “The Grampian”, a relatively luxurious passenger liner. Duties for the friends were light, supervising the men for lifeboat drill and watching for enemy ships, with the reassurance of accompanying destroyers. There were short stops at Gibraltar and Valetta, then at the great hub of Alexandria where the ship was restocked. The exotic surroundings and atmosphere were an adventure indeed.

After leaving home, in only a few short months they found themselves in the thick of it at Suvla Bay in Gallipoli, which Owen described in his diary, excerpts of which were published [1] as “the most barren, forbidding country in the whole world”

The disastrous story is well known, but a taste of the horror was described by Holleran:

“(the landing troops) were carrying their full kit most of the time and had only one quart of water per man during this time and the heat running from 90 to 100 degrees. Hundreds of men went mad from thirst and numbers of them drank seawater. The men who were wounded were practically without relief during this time, for it was impossible to get to them”

It was soon to be their turn. A landing and then a march, during which time his ear was nicked by a sniper – this was “lucky” as it could so easily been fatal.

“There is no “cease fire” in this war, it is one continuous grind. And there is no safety in Suvla, every place can be reached by the merry shall and we lose men in the rest camps as well as the firing line…….We must halt to wait for the guides….Going into the trenches for the first time is an experience in itself. Of course we had been in the communications trenches, but now we were off for the front line.

In Gallipoli the shortage of water was a very serious matter. Most days there was no allowance of drinking water and only about ¾ pint of a dirty liquid heavily impregnated with sand and officially called tea. There was never water to wash in.

The flies were different colours on various days. It became necessary to put currants in the rice to cover up the flies and to drink the liquid called tea through the teeth and scrape the loving fly off afterwards. This plague was caused by the hundreds of decomposing bodies between the trenches.”

Descriptions of “fatigues” follow in horrific detail, the “adventure” turning to hell when the Turks attacked. An order for two days rest was thankfully given. Holleran notes the roll call

“A Company 35 casualties, 160 men engaged. B company lost only 15 men, and C Company 27, But poor old C Company have only 74 men, half their strength. For the Battalion 141 hit on 524 men, leaving 483 effective”

Rumours began to fly and an unexpected order came to confirm a move. They boarded a filthy boat normally used for moving stock.

“This nice little excursion boat, made to carry 300 people or pigs, had close to 1,000 soldiers aboard, and in comparison, a sardine tin is a roomy place; further she had ambitions to become a submarine and when she was not trying to dive head first was endeavouring to roll over”

At Mudras they transferred to another vessel, and more rumours flew when warm clothes were distributed. Were they going to the Western Front?

“Where the hell are we?”

Holleran described Salonica Bay as “one of the most beautiful places in the world.” They had reached Greece, another exotic place with gaily dressed inhabitants. Here they had a few days rest but men were falling ill with dysentery and Holleran was concerned about a camp of Serbian refugees, stoically accepting their plight and said that “After Port Said Saloniki is the vilest city in the Mediterranean”.

A three-mile march took them to the cattle train, which was cramped but at least clean. Arrival greeted them with the desperate sight of women, children and old men carrying their pathetic possessions passing in a seemingly endless stream. The soldiers shared their rations and marched on, wading through mud where a bridge had collapsed. They were happy to join the great Athens to Constantinople Road and march on through the barren Serbian countryside, observing the pretty hill villages in the distance. It was noted that the women did the work, while their men guarded them – it was an area of tribal wars. There was fighting nearby involving the French and there were spies about and some shells falling. Eventually the Front Line was reached on 17 November and work began on dug-outs.

Just 500 yards from the Bulgar lines, it was dangerous to move about and the weather deteriorated quickly, with freezing temperatures and falling snow. The diary reads on 24 November:

“The rifles are so cold that your skin sticks to the steel…Saw a man offer another 100 franks to break his leg…..The platoon is getting weak, 9 and 10 joined B Company today because they lost nearly 60 men in twelve hours”

The days passed by, and more men were lost. After a short rest Owen was back at the Front on 28 November, enduring a march during which he twice fell, leaving him with swollen knees and being unable to take off his boots. The snow was four feet thick, temperatures well below freezing. Both his feet were frostbitten. He then was shot through his knee and was unable to move. He was sent to the overworked field ambulance. Ironically, after his request for “somewhere warm”, the extreme cold of Serbia caused the end of his army service.

Taken by a motor ambulance, he reached Saloniki in a delirious state on 1 December. He found himself on the Gascon hospital ship, in the care of Dr Murphy who intended to cut his knee. Free of lice at last, he was allowed a pint of cocoa with brandy (which he thought disgusting) before the operation. He soon felt better and was taken to Alexandria Hospital, in Egypt, hoping that by Christmas he would be in England.

Hopes for a quick recovery were dashed when a blister was found on his right foot and gangrene developed; he refused amputation. Taken to Blighty by the Dunluce Castle and HMS Britannia, Owen Cobb Holleran started the New Year with an unavoidable operation to amputate.

“January 1st Foot off at 8.30, under ether 3 and a half hours. All bones protruding, horrible looking mess. Am very weak”

He was then sent to Cliveden, where the Astor family had invited the Canadian Red Cross to build a military hospital on the estate. This was named the HRH Duchess of Connaught Hospital, and was a peaceful haven after the horrors of the war. Lady Astor was concerned about the convalescing soldiers, and as a fellow American she took a special interest in Holleran.

“February 3rd It’s not very serious, I’ll be able to walk practically as well as ever. Healing splendidly”

“March 6th, I have had another operation. Had to have the metatarsal bone of the big toe on the left foot removed”

Although he had been recommended for a commission this had never happened, and he explained the reason while he was recuperating.

“They wanted certificates stating that my father & grandfather were British subjects – and that while I was in the wilds of Serbia! My very good colonel undertook to handle the matter and I heard no more. However, Mrs Astor says she will get it or there will be a row”

Mrs Astor had plans for Holleran to serve in some capacity in the Irish Guards, an expensive regiment for officers, offering to equip him herself. He wrote home to ask for some paperwork – a certificate of efficiency and a certificate of education, at the same time, requesting recipes for a Martini and a Manhattan cocktail which the Medical Officer had wanted. The commission fell through and plans changed; he was told would be dismissed from the army and should head for home.

The stay at Cliveden lasted until he was fitted with prosthetics, and he did not intend to go home at all, believing that his fighting days had not ended just because he had lost his feet. He read about the development of a new aeroplane, which was operated by hand levers, and after giving the matter some thought decided to become an aviator. Surprisingly he was accepted for training in the Royal Flying Corps following his honourable discharge from the army

In February 1917 he was attached to No 39 Squadron RFC, and in Montrose (“a quaint place about 40 miles from anywhere, with the North Sea in sight”) for training. He immediately took to flying, felt fit and was happy. After training he joined 56 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps on 10 April 1917 and remained in Montrose but was shortly on his way to a base in England.

(Montrose Air Station was established by Winston Churchill in 1912, for the protection of Royal Navy bases at Rosyth, Cromarty and Scapa Flow. When the war began it became a Training Base.)

Meanwhile, in the West of Scotland the Duke of Argyll was in his castle in Inveraray. 1917 was a gloomy year, the fourth of the war, when news was bad and food in short supply. The Duke did his best to support his tenants and his friends during those very trying times. Arrangements were in place to ensure cheap food was available from the vast Estate. Deer were culled, salmon caught and rabbits killed, all to be sold in local shops at moderate and fixed prices. He was busy with Estate business, and obligations as Hon. Colonel of the 8th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, work he took very seriously. The weather was unusually cold, for April but he, like Holleran, was a happy man. Then a most unusual event took place on his estate.

In his compact diary, the Duke noted:

“An Aeroplane fell or came down at Cladich having missed its way in the Grampians through snowstorms, and Mr McIntyre of Drimlee was alarmed at hearing it descending above his house.”

(NB Drimlee was, and remains, the highest house in the quiet Glen Shira)

The next days were as busy as usual with a visit to Lochgilphead, further along Loch Fyne. He was to inspect the men training there, catch up with news from the officers, and meet with some of the 1/8th Battalion who were enjoying a few days’ leave. There was great excitement and a great deal of rumour in the area.

On Saturday 21 April Duke Niall wrote in his diary of his encounter with a young Irish American, Lieutenant Holleran, who was on his way to the castle to seek permission to take off with his aeroplane – the one which had landed at Cladich – from one of the flat fields on the estate.

Duke Niall was keen to help and showed the Lieutenant the Fisherland Park, which was pronounced to be suitable. The pilot told the Duke that he had been at the base in Montrose and on his way to Inverness to go on further south when the machine came down. Five other machines also landed in the storm. It was arranged that the young aviator should stay in the castle. During the evening Niall and his sister Niky (Lady Elspeth Campbell) were fascinated with talk of the aeroplanes, and were amazed to learn that it had taken only 40 minutes to fly from Inverness to Cladich. He spoke much about bombs dropping and the explosives used in them. On his part the Lieutenant was “much taken up” by the old armour in the hall.

The Duke thought Holleran a personable young man and was most intrigued by his knowledge of the new flying machines, but he also wanted to learn about his personal experience of the war.

Sunday came, and Niall cycled to church for the 8.30 mass, to find only his Aunt Conny and cousin Ernest there. On his return to the castle, he found there had been a further inspection of the places suitable for take-off. The Gallows field by the Aray Bridge was the final choice as the Lieutenant thought it better than the field at Cherry Park, so the aeroplane was taken over the river to the corner by the fank. Niall then returned to church for Matins, hurrying back to meet the Lieutenant so that he could look at the aeroplane and have the workings explained.

The Duke recorded in his diary for 22 April 1917:

“They are wonderful things but seem complicated. 6 mechanics who got here last night have begun the repairs. Not much was amiss except the undercarriage. All the Parish came to look at it during the day but he will not get away until Tuesday it is thought. His feet gave him such pain that he rested on getting back to the castle after going round by the Cairnbaan. He said the flesh was all gangerened & black and falling off to the bone in Serbia and that one day the doctor gave him only 12 hours to live, yet he drank some milk and pulled through.

He gave me a curious account of the Clan Feuds which go on amongst the Camerons, MacDonalds and MacDougalls in Kentucky and Tennessee. 5 years ago, one clan shot the judge and the whole of the jury in Court.

Horror throughout the world is shewn at the German exploitation of their own corpses which are converted into fats and glycerine even the bones are powdered down to feed pigs on.”

On Monday Niall read and wrote all morning, and in a conversation with Lieut. Holloran was told that Owen was “long in the hospital at Cliveden and that Waldorf Astor had been very kind to him and also Paul Phipps”

After transplanting some azaleas, Niall again visited the aeroplane in the corner of the field, and saw that all 6 mechanics were working on the machine.

“I was struck at the fine wire with its sharp edge to the front to minimise resistance, and the way it was singing although there seemed to be no wind. The Lieut. Had to return by train to Montrose, leaving here at 5.00pm to complete tests and he says either he or someone else will return on Wednesday and fly this machine home, touching at Turnhouse near Edinburgh first. He has also been at Suvla Bay it seems”

The aeroplane was ready on Tuesday and all the mechanics went to look around the castle but news came that the airmen would arrive on another machine and take both back on Thursday. Four machines would arrive with five officers in time for breakfast. The plan was very exciting for the Duke and all the local people.

Anticipation was sky high when the Duke rose very early on Thursday morning, going outside to find that the first swallows had arrived. A message came by telephone that the aeroplanes would arrive at 11.00. He quickly took breakfast and rushed out again. His diary for 26 April 1917 tells of the drama of the day:

“Aunt Conny had been up since 8AM wildly excited. We all waited in the W corner of the field at about 11-30 there was a shout from the mechanics who had seen Davis the pilot(‘s) machine coming over the glen from Lochgoilhead, he soon crossed Strone Point and circled high in the air, stalled above the loch and from a good height glided down over the Kilmalew gate onto the north end taking a long run over the grass till he stopped. The people all hiding under the trees. Holloran stepped out with Davis and said they had come by the Trossachs, Loch Long and Loch Goil Keeping low on account of the dense hill clouds, they had to turn back from Glen Croe when a frightful air bump which had been as much as the machine would stand. Next came Lieut. Perfect who has not yet got his wings quite alone and he made a very easy landing near the fank fence & was complimented by Davis. They all came up for lunch at the house and have to stay the night as it is too cloudy on the hills for the 2 younger ones to return. We have heard that the 3rd plane had come down at Stirling and the 4th missing his way at Portkill at Rosneth in that field by the Fort. After lunch Davis took Ernest Emmott up first, looping the loop with him over the pier & did awful turns and twists. Then Niky went up with him and was taken at 120 miles an hour to Monerechtan (above Lochgilphead) she looked down on Dunderave and Laglingartan from a height of 2,000ft, & through some wisps of clouds and was back in about 10 minutes & left after flying over the Kilmalew Gate, close to the Mound. Then he took me up (my first experience) we rushed over the grass at 50 miles an hour rose to clear the trees river and castle flew over the Fisherland Winterton and looked down on the town and Muir from a height of 1500 ft., then we looped the loop and happily the broad belt straps one in tight. I did not like that part of it as it makes one feel sick also we did a steep turn & I shut my eyes. The whole populace were gaping up in astonishment. We did a turn by Strone 120 miles with the wind & the across & down to Polchline at the rate of 70 miles, the loch waves and ripples quite disappear at that height we turned back to Strone Point coming down out of what seemed dense cotton wool then a delightful plane down to Kilmaleau and hit at about 60 miles an hour feeling no bump, between the Gallows mound and the other beech. The Leather coat, Helmet and Gauntlets keep one warm, & spectacles for the eyes and there is a slight wind (illegible). The Propeller is in front and so really the machine is being snicked (?sp) forward Aeroplanes are wonderful things but breathing is not easy against the wind at times and it is a pity that the clouds prevented a distant view. I took Perfect and Davis for a walk after tea through the (ends here).”

It is evident that this was an exciting, memorable and novel experience for the Duke who wrote his diary entry at high speed while everything was fresh in his mind. The entry for Friday was much shorter, recording that

“Lieutenant Godfrey Davis left early after lunch by Aeroplane from the Gallowsfield. It was far from a nice day. He did several trial flights before just missing the trees it seemed to us. He told me he did not like to advise the two others to leave on account of the air pockets and hill mists and in the end I persuaded Holloran and Perfect to stay till the next day and we had an interesting evenings talk with them”

The newspapers picked up on the story, on 5 May the Oban Times reported

“Last week a squadron of airships visited this district and made the Stable Park their headquarters. The officers were entertained by the Duke of Argyll. A fine display of work in the air was given, which was watched with deep interest by the residents in the town and district. The greater number of them had never seen an airship before”

It is interesting to note that the term airship is used to describe the aeroplanes; new machines and new terminology that people were not quite used to.

There was a sad outcome for one of the pilots who landed in Inveraray who was killed in a crash shortly afterwards, as recounted in a letter from the Duke’s sister, Lady Elspeth which arrived after she had been in Edinburgh and had, by chance met an Air Sgt who had been at Inverary.

Life settled into the usual wartime routine for the Duke, but the memory of the interlude with the Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines must have lingered throughout his life, and he gained a new title “The Ducal Aeronaught”.

Holleran’s career in the RFC makes many adventure stories seem tame. He was credited with bringing down five German planes, and had three wound stripes. In April 1918 he was posted to 85 Squadron but only a few days later found himself back with 56 Squadron. This Squadron had achieved the reputation of being fierce fighters with outstanding pilots like Albert Ball, Cecil Lewis and James MaCudden.

The team was equipped with the new plane – the Royal Aircraft Factory SE5 fighter. A strongly built single seater biplane, it had a few problems which were ironed out and modifications resulted in the SE 5A. The engine was either a Hispano-Suiza or a Wolseley Viper, with a maximum speed of 132 mph, maximum height of 20,000 ft, and flying time of 2 ½ hours. The wingspan was 26 ft 71/2 ins, the length 20ft 11 ins. and it weighed 2048lbs loaded. There was a fixed Vickers gun, and fixed to the upper wing was a Lewis machine gun which could be moved up and down but not swung sideways.

Above: S.E.5a aircraft - The wartime censor removed the serial numbers. Photo - Public Domain

His first duties were not as exciting as he hoped, as he was based at Scampton in Lincolnshire, where he underwent “post graduate” training in the fast machines. Another move came in May 1917, to South Charlton, also in Lincolnshire. Acting as an assistant instructor, he felt the responsibility of keeping his sometimes reckless pupils safe (the accident rate for trainees was very high), but generally felt that the place was dull. He was pleased to receive invitations from the Astors at Cliveden, and from the Duke of Argyll to stay at Inveraray, but could not get leave, and had to send letters of apology. More training at Scampton followed, enlivened by a German attack on the base, and he spent Christmas there, concerned about news of the war. During the following months of awful weather Holleran was really fed up and seriously considering resigning and returning to the USA to seek an appointment with the US Army. He was fully trained, and fitter than he had ever been, greatly frustrated that he was not at the Front.

By May Holleran was feeling much happier and at last based in France. Unable to suppress his sense of humour while writing his required will, a fellow flier overheard him say to the Commanding Officer: “Well Sir, I am a Socialist and I believe in Socialism. I have nothing and I want to divide it with everybody”

He was also mischievous, getting himself into trouble when, in the company of another ‘plane, they chased a visiting dignitary across the sands at Paris Plage. After landing and duly giving a reprimand, the General made for his car, which was suddenly attacked by a German bomber. The car was demolished, but fortunately no-one was hurt.

It is easy to understand why these lighter moments were enjoyed when reading more serious extracts from Holleran’s diary and records of his time during the war.

“During the night a Hun machine came over and deliberately bombed No.3 Canadian Hospital at Doullens. Three nurses, four surgeons and a large number of enlisted staff and patients were killed and injured. The first instance I have personally seen of deliberate destruction of hospitals….No mistake”

(3 Nurses and 29 other people died on the last two days of May)

While flying SE5 C5434 on 26 June 1918?? Holleran was wounded in the shin and needed some treatment. That day he shot down three German planes. He was able to take leave and after an uncomfortable journey in a sidecar reached Boulogne where he had a luxurious room but suffered the effects of an anti-typhoid injection. He then reached London and made the most of his rest. He met friends and dined out at Prince’s, and they visited the Alhambra theatre. August saw him back in France, but he developed an abscess and was sick for fourteen days, causing him great frustration.

Returning to good health, the excitement he had craved was waiting for him in plenty. On 8 August the Allied Offensive began with the Battle of Amiens.

With other aircraft, 56 squadron was to help with ground attack on the German’s Epiney aerodrome. There were over 100 25lb bombs dropped and 10,000 bullets fired, the attack being photographed.

“When I got set to fly again things happened in quick succession. First place the CO gave me a flight, so I am a Captain now. Then we started our usual patrol of five to ten machines with two near tragedies on the 13th. First, 16 Huns got after two of my fellows and myself, but I outran them. They had one splendid opportunity to make things hot for us but it only lasted a fraction of a second. Later in the day sixty odd Huns got after eight of us but we absolutely bluffed them. And we were nearly 15 miles over their side when we met them.”

In August Holleran led an attack across the German line, and a large group of Fokkers was seen, estimated at 100 machines. Heavily outnumbered and with the Germans in an advantageous position above them, Holleran and his comrades successfully evaded them, allowing the British planes working below to continue their observations.

Another patrol the following day saw no engagement, but six enemy planes were chased and a second raid in the evening added to the valuable experience the pilots were accumulating.

Holleran wrote of concerns for one of his men who had been shot down and captured - was he in the German hospital he himself was strafing? The following day he was chased off when trying to down a balloon, but he went back to base, loaded more bombs and went to strafe the AA batteries. This was not enough for him, as he reloaded at base once more and went back to finish the job. The weeks were extremely busy, with an exceptional operation on 11 September 1918?

“Most exciting bit of sport I have had in some time. Incidentally we chased a bunch of French Cavalry all over the landscape. Larry Bowen and I were coming along the bottom of a valley leading to Doullens. The valley ends in a rather steep hill and just beyond the crest of the hill is a road. No one can see the valley from the road and vice versa. So, when we suddenly rose out over the crest with a roar the Froggies naturally concluded that we were evil and promptly lived up to the soldiers’ maxim; when you hear an unfamiliar noise don’t be curious, DUCK”

15 September started badly with Holleran’s fellow Commander Captain, (William) Roy Irwin, attacked by Fokkers and seriously wounded, his days with the squadron over. They were ordered to attack the German aerodrome at Estourmel (Boistrancourt) led by Major Gichrist. The raid saw bombs dropped, planes and sheds damaged, sadly Larty Bowen, who was in the same hut as Holleran, was killed. The raid over with the planes leaving the German lines, and Holleran’s plane was hit. It was claimed by Lt Georg. Meyer of Jasta 37, a German Ace, but other reports say that he was hit by an “Archie” – an anti-aircraft gun. He managed to land his machine and attempted to burn his ‘plane, but his torch failed. He was quickly surrounded by the enemy, and raised his hands in surrender. His comrades in the air saw him giving a cheery wave from the ground. He was taken prisoner but posted “missing” and feared dead but eventually it was confirmed that he had been taken prisoner.

Owen later remembered the event:

“When we were just about the centre of the square I saw my last scrap. Five Camels dropped on seven Fokkers. The Camel leader got a good burst into a Fokker who promptly fell apart. Two more came down in flames and the rest of them ran”

I have been unable to find where he was held captive during the months he was a prisoner, but he was released in Berne in Switzerland in November 1918. After repatriation he arrived at Dover on 5 December 1918 and appears to have spent some months in the RAF hospital in Hampstead, his injuries still causing him problems.

He was carrying out non-flying duties with a training group, (RAF 24), but his last UK address on entry back to the United States was given as Queen Mary’s Hospital, which specialised in amputations, and was nicknamed “The Human Repair Factory”, indicating that he was having further treatment for the injuries he sustained in 1916.

Owen Holleran sailed for home on the SS Magantic, leaving Liverpool on 15 September 1919. The voyage was paid for by the British Government, and the official paperwork describes him as having dark hair and brown eyes and being 5ft 9” tall. Also aboard the ship was a Canadian pilot, Wilfred Leigh Brintall, and the two may well have discussed ‘planes and compared their wartime exploits. Owen headed for his family in Atlanta, staying with his parents and reuniting with his younger brother Cecil.

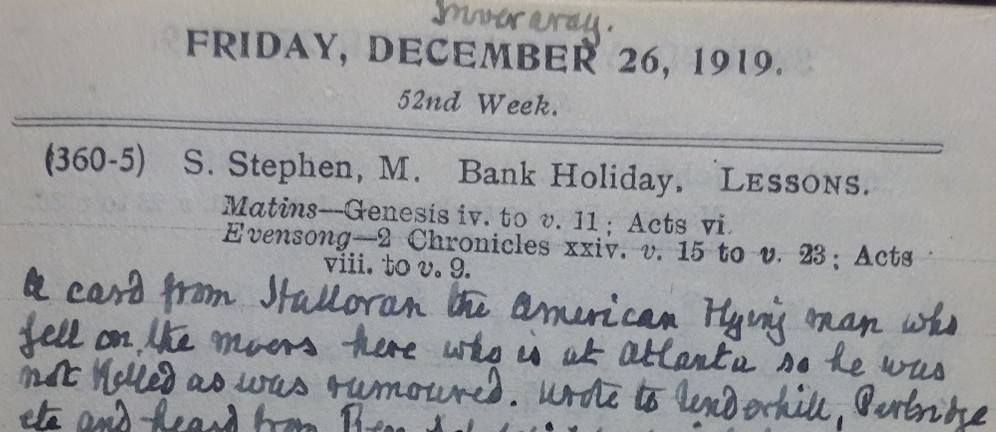

After his Great Adventure, Owen’s life in the USA resumed. He relinquished his commission on the grounds of ill health on 26 September 1919.But his encounter with the Duke of Argyll had clearly not been forgotten as recorded in Duke Niall’s diary in December 1919.

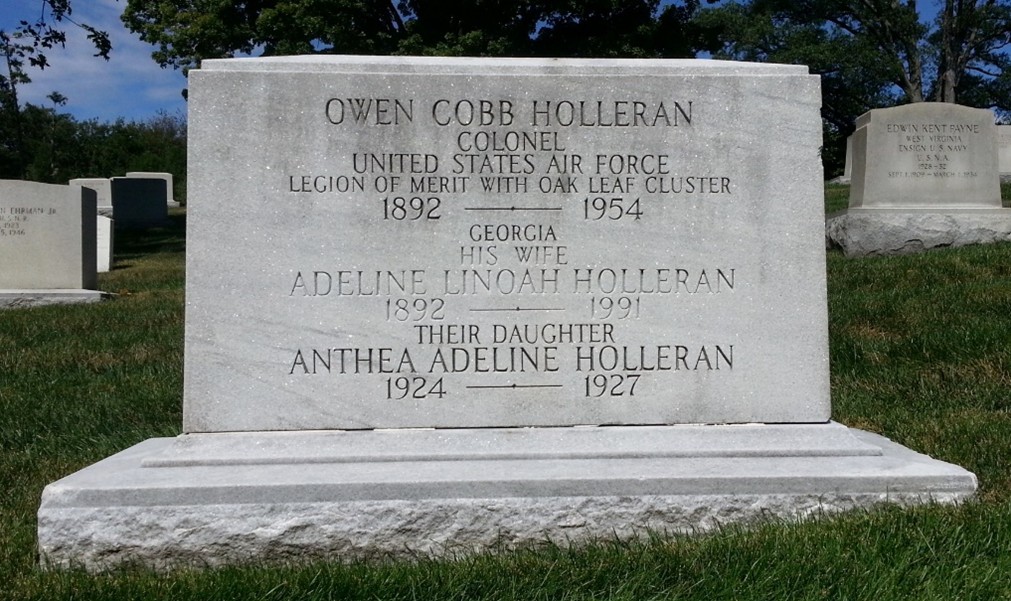

Owens’ return to civilian life can be traced in US records and mentions in newspapers. In 1920 he had gone “home”, living with his parents and brother Cecil at 146 Highland Way in Atlanta, his occupation noted as pilot. In February 1921 he married Adeline L. Amstutz in Savannah. They had two daughters, Nancy Christine and Anthea Adeline, and a son Owen Cobb. Anthea died from diphtheria when she was only 2 years old. In 1930 the family were living in Springdale Road La Grange, about 60 miles from Atlanta and he was working as an Advertising Manager. From then he worked as an Industrial Analyst for the government and the family lived in Washington DC.

He published a book “Holly” recording his life during the war, and during the 1930s he regularly gave talks about his adventures.

At the early age of 61, Owen Cobb Holleran died of a heart attack, and he is buried at Arlington Cemetery. He was living with Adeline at 146 Connecticut Avenue and working as an Industrial Examiner for the US Air Force.

Additional notes

Meredith Gray returned to Ireland after his own problems with frostbite in Serbia and was commissioned as Second Lieutenant. He was married while on leave and shortly afterwards posted to the Western Front. He died on 16 August 1916 at the Battle of Vimy Ridge

Albert S Mathieu does not appear in any of the usual records, but featured in a 1919 newspaper article in Atlanta, talking of his war experiences in Palestine and mentioning the names of Owen and Meredith.

Godfrey Davis, one of the pilots landing near Inveraray, was taken prisoner, shot down in 1917 by Erwin Böhme, a German fighter ace credited with 24 aerial victories, and was repatriated in November 1918. He founded the largest car hire company in the UK, which had over 3,000 cars at the time of his death in 1961.

Owen Cobb Holleran Jnr, Owen’s son, served in the US Army in Korea and Vietnam, and was decorated several times. He served as a civilian employee of the Army in the USA and Germany and then worked at the Pentagon, returning to Atlanta on retirement where he took a full part in community life. He died in May 2021.

Owen and Adeline’s daughter Nancy Christine married an Italian book-keeper, Angelo Marotta and had two children: she died in 2010. Adeline worked with various community projects and died at the great age of 99 in 1991.

There were several grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Article contributed by Ann Galliard

[1] Published in ‘HOLLY, His Book. Being A Diary of the Great War.’ Holleran, Owen Cobb

All quotations retain original spelling and punctuation.

Thanks are due to the Argyll Estates Archive.