Caught in the Crossfire: Canadian Snipers and Open Warfare by Leslie P. Mepham

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Caught in the Crossfire: Canadian Snipers and Open Warfare by Leslie P. Mepham

(Originally published on Stand To! No.55 (April 1999 pp. 17-20.). Made freely available as key material for the online course The Imperial Western Front created in conjunction with the University of Kent).

Introduction

Sniping has long been forgotten in the Great War. More often than not, the sniper receives little scrutiny in military history books, so little in fact that Paddy Griffith maintains, 'snipers appear to have been so successful in their undercover activities that they have left few traces in the general literature of the war.' (1) Nevertheless, the sniper was highly effective on the Western Front, particularly in the trench warfare that characterised the Great War. Though initiated by the Germans, sniping was refined by the British and Canadian Forces; the British provided the outlet for sniper schools, the Canadians for their hunter and frontier lifestyle. By late 1916 sniper schools appeared all across the British and Canadian fronts training already proficient marksmen. From the trenches they executed their art, and subsequently their prey, at all hours of the day in a variety of techniques. In fact, even in times of lull and quiet on the Western Front,' the sniper served to remind the soldiers that they were still at war. (2)

Sniping, despite finding resounding success in the trenches of the Western Front, still had a role to play in open warfare. In the BEF and Canada Corps, some of the upper echelons of the military hierarchy believed that the sniper was a product of trench warfare. In fact, 'the officers who believed this prophesied that when warfare became once more open, he would be useless.' (3) This article aims to dispel that myth and show that the sniper was highly active in open operations throughout the war. The offensive, a regular venture used to break the stagnation of trench warfare, found the sniper most useful; his activities were continuously put to work, from before zero hour to consolidation of the newly-won line. Secondly, the mobile warfare that characterised the summer of 1918 also made room for the sniper, ensuring that the faltering enemy was put down by a well aimed rifle. In summary, the sniper's art was very active in open warfare and his contribution was as much a part of victory as the men who surrendered their lives for it.

Sniping in offensive operations

While snipers found their most congenial role in the trenches, they did have a place in offensive operations. Much like all other branches in the Canada Corps, snipers had preparatory work to do before the attack. Moreover, while many first-rate snipers rarely joined the 'over the top' rush, they still provided assistance during the assault. Lastly, once an objective was gained, skilled marksmen assisted in the consolidation of newly-gained territory. While it would be difficult - and unnecessary - to describe sniper activities in all the major campaigns involving the Canada Corps, this section will correlate the before, during and after stages of the attack while reflecting on certain examples from some of Canada's major triumphs (i.e.. the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele). (4)

Prior to a major offensive, the Canada Corps had many preparations to make. In fact, preparation became one of the key ingredients in ensuring success. Following the Somme campaign, the Canada Corps began to learn regularly from their mishaps and refined their methods. (5) Preparation eventually amounted to playing out the attack on a model battlefield behind the forward line, as they did for the Vimy Ridge effort. Nevertheless, while mule trains and boxcars brought supplies to the front, and artillery formed up along the rearward lines, the infantry prepared for the assault by grouping into respective Company Sections. Reliefs took place over an eight to twelve-day period, moving new troops in small parties over the course of the day. The attacking units typically remained in the rear lines until shortly before the assault. Specialists, including snipers, went into the line approximately twelve hours before the rest of the battalion. (6) Observers, meanwhile, continued to monitor the enemy line, reporting their findings every twenty-four hours. Battalion Scout Officers put their men to work checking up on positions in their own line as well as those of the enemy. Snipers usually took up flanking positions in the forward trenches, sniping from posts hidden in the parapet. Sniping before the assault was critical as it kept the enemy's observation in check. (7) Moreover, it had the combined effect of lowering enemy morale while increasing their casualty rates. For instance, in the three months preceding the attack on Vimy Ridge, 9 April 1917, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions combined to eliminate 406 of the enemy - the 3rd Division with 262 kills alone. (8) In some sectors of the Vimy front, no man's land extended 500-1000 yards and thus, sniping opportunities in these areas were not as plentiful.

When sniping opportunities were not quite as frequent, Canadian marksmen practised behind the lines on rifle ranges, continually refining their shooting finesse. (9) Distance of the ranges was usually 100-150 yards where grouping and snap shooting took place. Practice on dummy heads, or 'Bosche heads' as they were sometimes called, was also carried out. (10) Where available, 200-yard ranges provided the sniper with greater skills- testing on the same targets. Much like a miniature course from a Sniper and Observation School, these practice sessions also familiarised the sniper with concealment via use of natural cover (e.g ... houses, hedges, ditches etc.) in open warfare.

As zero hour approached, and while the artillery prepared for the preliminary bombardment, Battalion snipers moved into place in the early morning hours before the assault. In an attack on 31 October, 1916, snipers '[positioned] themselves before dawn within fifty to sixty yards of the enemy front line, to snuff out any troublesome machine guns during the crucial moments of the attack itself. Others [occupied] positions overwatching more distant flanks, with the same purpose.' (11) Shortly before the attack, the artillery shelling began in an effort to break up German lines, wire, and communications. Even in this early stage of the attack, the snipers provided assistance via their accurate rifle fire. In one of the first raids featuring the Canadians - Douve River, 16-17 November, 1915 - 'the bombardment was augmented by sniper fire, the Battalion's rifle fire and rifle-grenades.' (12) The added rifle fire ensured that casualties were inflicted and the movement of reserves retarded.

Once the shelling had done its damage, the large guns launched the 'rolling barrage'. The barrage (from the French verb barrer, to bar), was first used at the battle of Neuve Chapelle, 10-12 March, 1915. Basically, the rolling barrage was a moving wall of exploding shells which hit an aimed objective, lifted and moved on to the next one. (13) It provided the moving infantry with some degree of cover, and because it moved forward at timed intervals allowed the men to proceed to their objectives with moderate safety.

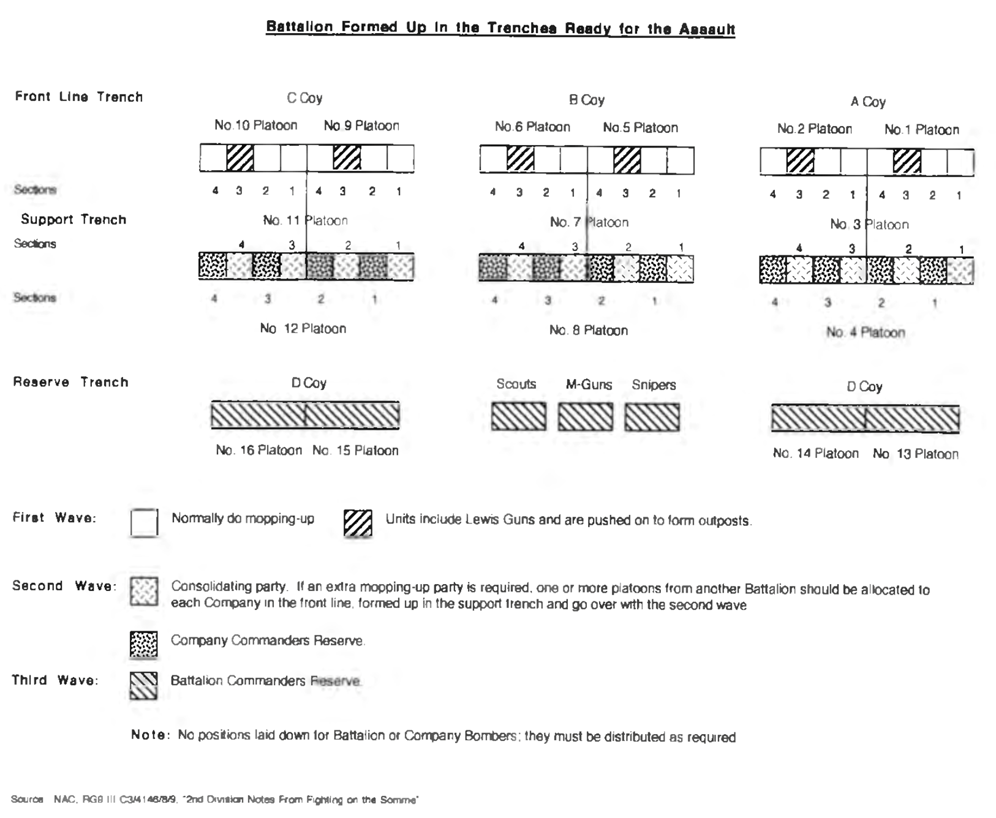

Slightly before the infantry went 'over the top', all attacking units formed up in their respective trenches. The front and support lines housed two waves of attacking infantry, a total of six platoons. The former followed the moving barrage and made initial contact while the latter followed for consolidation purposes. In the reserve trench, two adjoining platoons and a specialist section of scouts, machine gunners and snipers made up the third wave. The diagram on page 17 provides an illustration of how these units formed up prior to action on the Somme, 1916.

In the aftermath of the Somme campaign, military strategists realised the importance of snipers in open warfare; hence they were given freedom of movement, or a 'roving commission', when crossing no man's land and beyond. (14) The reason for this situation is clear. Moving in packs presented more favourable targets for enemy machine gunners and since quality snipers were few and far between, it was better that they be on their own. Company snipers, usually of lesser skill than Battalion snipers, often joined the rush across no man's land with their platoon, taking advantage of targets which presented themselves. (15) Once they reached their first objective, they remained in the open, watching for enemy retaliation or machine guns while the ordinary infantry went about the trench clearing process. (16) Battalion snipers, in the second or third wave, usually adopted flanking positions during the advance, attempting to cover the moving infantry. (17)

Once the latter had reached the first objective, Battalion snipers, like Company marksmen, worked through the battlefield searching for posts to conceal themselves. In no man's land, makeshift sniping posts were a rarity, and snipers were forced to improvise. Those most abundantly found were the shell holes which irregularly decorated the open battlefield. In advances of 500 yards or more, snipers sometimes 'dug in' at the back of a crater, sometimes carrying with them a metal loophole plate. (18) The plate, placed overhead, offered protection from stray bullets and shrapnel. From this point, the sharpshooter could carefully watch for and fire upon targets in the enemy line. Another alternative to the dugout was to lie upon the front lip of the crater and snipe from there. In one instance, a small group of snipers moved from shell hole to shell hole, sniping at targets as they moved closer to enemy lines. However, as Herbert McBride notes, in a constantly changing battlefield, it was critical for the sniper to adapt and take advantage of natural cover:

In any sort of advance, the type of country and surroundings may undergo a decided change. One moves from the flattened out country of shell holes and blown down buildings over into comparatively open ground, with growing vegetation and standing buildings - plenty of cover of an entirely different colour and type. He must be able to adapt himself to all sorts of restricted positions and still deliver accurate fire. (19)

When mop-up crews, i.e. the first wave, moved through a town or village, snipers took advantage of buildings and ruins to conceal themselves. Rooms in houses, roofs and chimney pots were common areas from where to conduct precision shooting. (20) The expanded field of view offered better sniping opportunities and protection, though there was always the hazard of artillery shells. When doors or windows were too revealing, snipers improvised by removing a brick from an unscathed wall to do their work. In small towns and villages the sniper was essential to the further advancement of the infantry. Enemy snipers often occupied cellars of buildings, at Courcelette for instance, shooting at troops as they passed by. (21) In this scenario, one would often see sniper versus sniper as company marksmen were often sent in to eliminate the enemy crackshot.

There were three main targets at which the sniper directed most of his fire. The machine gun, perhaps the fiercest enemy on the battlefield, was the primary target. (22) Machine guns often held up moving parties for long periods of time or otherwise cut them down with heavy fire before they could get anywhere. Thus, it was the sniper's task to put the gun, and its operator, out of action. Machine guns were often concealed and rarely in the open for shooting; in such a case, the sharpshooter consistently aimed for the gunner since they were 'hard to replace and fire directed by untrained machine gunners [was] not very formidable to tackle.' (23) As the war carried on, snipers began to opt for the gun itself - trying to lodge a bullet in the breech or mechanism with armour piercing ammunition. (24) Sniping from prepared positions in no man's land offered some protection for the advancing infantry:

This method was very successfully adopted by a sniper o f the 29th Bn. during the fighting on the Somme. He dug in during the night within 60 yards of the German parapet and in the early morning when a Company of the 29th advanced it was held up by M.G. fire, L/Cpl. Pumphrey spotted the M.G. and aiming carefully through the aperture, he fired a shot and the M.G. stopped, again it opened up, and after the 2nd shot it stopped. Again it opened up and with the 3rd shot it stopped altogether, the Company carried on with the advance, and later, on entering the trench and examining the M .G. post they found two dead Machine Gunners and a bullet through the mechanism of the gun which put it out of action. (25)

Canadian snipers were exceptional in this category, and Hesketh-Prichard credited them for their skill:

In the last advance of the Canadian Corps, their very skilled sniping officer, Major Armstrong, told me that a single sniper put out of action a battery of 5.9 guns, shooting down one after another the German officer and the men who served it - a great piece of work, and one thoroughly worthy of General Currie's splendid Corps. (26)

The other two targets favoured by marksmen were officers and supply trains. After any bombardment, officers and NCOs emerged to gather the remainder of the unit and conduct operations first-hand. These targets were favourites of many sharpshooters as many German officers began removing their epaulettes when touring the trenches. In regards to the supply trains, loads carried to the front lines were broken up by sniper fire, anything to hinder the defence of enemy lines. (27) Beyond these favoured targets, snipers usually sought after their enemy counterparts, preferring to leave the masses to the masses. Though in some instances - like the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry attack at the Battle of the Scarpe, August, 1918 - 'snipers were posted in a position where they could enfilade the trench.'(28)

Using telescopic sights in the field was difficult during the offensive. Conditions on the battlefield often rendered them useless. After preliminary shelling or the barrage, visibility was often minimal and dirt and clutter abounded over the terrain. In the more drastic conditions, such as Passchendaele, October-November, 1917, snipers were ordered to leave their telescopic-sighted rifles behind. (29) When conditions were slightly more favourable, many snipers chose to take an ordinary rifle with iron sights since a telescopic sight could be misaligned when crossing the battlefield. Some, like McBride, preferred to use both, choosing one over the other depending on the situation. (30) The open or iron sight was useful for practical shooting and clear targets; more distant prey typically required visual assistance. Here, McBride accounts for the conditions on the battlefield: 'The battlefield soon takes on a weird and grotesque appearance, and ordinary objects such as trees, bushes, stone walls building and such become so disrupted and twisted out of shape that they look like such things as one sees in a mad dream.' (31) McBride noted that seeing through a telescopic sight in these conditions was often difficult, but on certain occasions, it made the difference between a hit and a miss. Only the most highly-skilled marksmen routinely brought telescopic sights with them and they commonly took up flanking positions, well away from the chaos.

Once the first objective had been stormed, and provided the assault was successful, the consolidation process began. As the infantry secured the first ground, the second wave 'leapfrogged' over them and pushed on to farther objectives. In this instance, snipers moved with the 'leap froggers' to more forward positions in an effort to 'cut off any Germans who might be retreating overland.' (32) At times, snipers combined their work with Lewis gunners, who also moved forward, to keep German movement limited and their efforts for a counter attack quelled. Quite often, a sniping patrol was sent out after consolidation to oversee the enemy's movement. In the Battle of the Scarpe, the PPCLI did so and spotted the enemy regrouping for a potential counterattack. Between the snipers and the Lewis gun crews that were subsequently brought up, the German efforts were thwarted. (33) After the taking of Vimy Ridge in April 1917, L/Cpl. Norwest, of the 50th Bn was instrumental in sniping at the enemy from the 'Pimple'. (34) It was here that he first earned the Military Medal; two Bars soon followed.

Acting as a communication line was another duty for the sniper after the campaign. Communications were very often slipshod after an assault; telephone lines were usually broken by shells and shrapnel, pigeons were not always reliable, and signallers were constantly obscured by smoke. The runner, it seemed, continued to be the most reliable form of communication. Nevertheless, snipers recorded their observations when in forward positions and sent them back to runners behind the line. After all, the sniper was to observe as well as kill. At the Somme, 1916, snipers provided important information about the enemy's lines that later helped the infantry in the capture of Courcelette. (35) In another example, L/Cpl. Paudash (21st Bn.), won the Military Medal for informing Brigade Headquarters of a pending German counterattack at Hill 70. (36) The counterattack took place within twenty-five minutes, but the Battalion, already well informed of the coming action, was ready for the assault. As the battle died down, and as new troops rushed in, snipers went about their usual business, seeking out new posts to conduct their work. At Vimy Ridge the Canadian Corps gained higher ground which almost always offered quality sniping opportunities. That snipers assisted in the consolidation process made securing newly-gained territory all the more effective. In general, Division, Brigade and Battalion CO's were impressed with the sniper's activities in the offensive, both in their own work and their assistance to the other men in the unit. (37)

Sniping in the last year of the war

After the horrors of Passchendaele November, 1917 had subsided, the Canadian Corps continued to refine their tactics and prepare for the coming year. While the military and political elite argued over the need for another offensive, the tank was finally used in a successful assault at Cambrai, 20 November 1917. (38) Generals now believed that truly open warfare could occur in 1918 and all forces, including the Canadian Corps, prepared for a campaign of manoeuvre. Training programmes in the CEF emphasised movement and consolidation:

Should the enemy retreat, the Canadians were expected to advance from one tactical point to the next, units leapfrogging at prearranged boundaries. Scouts would lead, followed by advance platoons, themselves followed by the remainder of the company. As usual, troops were to advance under cover o f rifle and Lewis- gunfire, and when the pursuit slowed to a crawl, they could consolidate their positions by digging in. (39)

The German offensive of March 1918 thwarted any short-term plans for a large campaign, and fortunately for the Canadians, the British bore the brunt of the German attack. Although the Germans pushed their way back into regions of Belgium and France, the effort eventually withered away through the summer, weakened by reduced manpower and resources. By August, 1918, the Allies - with new, fresh support from American forces - prepared for the coming offensive.

With regard to sniping there is some disagreement over its employment in mobile warfare. As early as the summer of 1917, sniping was taking a back seat to scouting and observation in the military hierarchy. Orders from the BEF's First Army show that the syllabi at Sniper, Observation and Scouting Schools were to be changed due to a decreasing role in open warfare. (40) 'In view of the more open nature of fighting which is now taking place, scouting and observation have become of increased importance as opposed to sniping and the use of telescopic sights of trench warfare.' (41) Despite the sniper having creditable roles in the offensive, higher authorities felt that sniping was of decreased value and, in some instances, their claim was supported by officers in the field. In response to a post-war memo on the value of snipers in mobile warfare, some battalions provided a negative reply. Without specific instances to draw from, these few units felt that there was 'never time or opportunity to practise [their] art' and that their value was comparatively nil. (42) Others still felt that regular infantry, provided with good musketry training, could deal with targets just as well. (43) A select few remained indifferent, noting that snipers could not always use their telescopic sights as effectively as in the trenches. (44)

There was, however, resounding support for the sniper in open warfare from the majority of the Canada Corps. Many units concurred that sniping opportunities were fewer in the open, but their value in the pursuit over open territory remained high. (45) In one instance, Brigadier- General T.L. Tremblay (5th Inf. Bde.) praised the snipers for they could often 'do the work of several riflemen who [were] not accustomed to making use of ground.' (46) Following upon this remark was the CO of the 31st Bn. who believed, contrary to the earlier remark about good musketry skills for the infantry, that snipers could engage targets that regular infantry could not. (47) By and large, the fact that the sniper was instrumental in taking out machine guns and their operators still made him essential to open warfare. Though trench conditions had declined by the summer of 1918, the machine gun was still a threat to the advance. Thus, the sniper was equally important in the assault in 1918 as he was at the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele. One Brigadier-General, D.M. Ormond even suggested that a Corps of snipers be formed and 'distributed amongst infantry battalions during active operations.' (48)

Indeed, specific instances show that the sniper was invaluable to operations during the last 100 days of the war. In the assault on Mericourt, 9 August 1918, members of the 22nd Bn. were covered by their snipers while they consolidated the captured line. (49) On August 28th, 1918 near Boiry and Artillery Hill, two 58th Bn. snipers took position on the roof of a house knocking out 20 German machine gunners and four machine guns at a range of 300-600 yards. (50) Several other reports indicate snipers' activity with resounding success against machine guns, German officers and NCOs and enemy snipers.

It is interesting to note in these positive responses to sniping in open warfare, that a number of battalions used their snipers on a regular basis. Those not in favour had no instances to draw from, implying that snipers may not have been used to the best degree. Moreover, some of those in favour were units from Western Canada where hunters and good riflemen were more abundant. Native Canadians, who were among the best snipers in the Canada Corps, were typically from the west, including L/Cpl. Norwest. Perhaps it was this added skill by western marksmen that helped to promote the sniper in open warfare.

The remaining days of the war showed even greater success for the Canada Corps. This elite force, hardly an army prior to 1914, had evolved into one of the best armies on the Western Front. An efficient use of infantry and artillery finally brought the Canadians to the Belgian border by November, 1918. By the time of the armistice, 11 November 1918, the Corps was over four miles beyond the town of Mons. (51) The Canadians' adaptability to open warfare, and the German capitulation in face of declining resources, ensured victory in the late fall of 1918. Though the sniper found fewer targets in the 'pursuit to Mons', he nevertheless played an essential role in the advancement of the infantry. He is as much to be praised as the soldiers who contributed to the defeat of Germany in the Great War.

Conclusion

This article has tried to demonstrate the great value of the sniper in open warfare. Though some believed that his art would vanish with the trenches, the sniper's ability to use precision shooting in the open proved otherwise. Under the horrible conditions of trench warfare, the sniper proved his value in all stages of the offensive. Even as the 'over the top' trench battles gave way to the mobile fighting of 1918, the sniper still found a place in the rolling campaigns into Belgium. His ability to cause casualties and inhibit enemy gunfire, though only a small piece of the puzzle, contributed to the larger picture and victory on the Western Front.

Sniping, however, was as much a casualty as the many soldiers who lost their lives on the fields of France and Flanders. According to N.A.D. Armstrong, 'there appeared to be a tendency among Army musketry to scorn the sniper - they held that sniping was only a "phenomenon" of trench warfare and would not likely occur again.' (52) Armstrong later stated that sniping was forgotten and the Battalion Intelligence Section was removed from the Army's establishment. (53) As this article has shown, sniping was not an exclusive product of trench warfare, and the sniper's ability to practise his art in the open proves this proposition clearly. As the war drew to a close in the first days of November, the sniper had outlived the prediction that sniping would die in the trenches.

[Article by Les Mepham who teaches history at the University of Windsor, Ontario. This article is based upon his recent Master's thesis.]

References

KEY:

NAC National Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

RG Record Group / volume / folder / file

MG Manuscript Group

|

1 |

Paddy Griffith: BattleTactics of the Western Front (London, 1994). p.73 |

|

2 |

Tony Ashworth: Trench Warfare: The Live and Let Live System (New York, 1980). p.57 |

|

3 |

Maj. H. Hesketh-Prichard: Sniping in France (London, 1920). p.26. |

|

4 |

Some historians may consider the Somme and Passchendaele campaigns to be more disastrous than triumphant. The Canada Corps, however, did succeed in achieving their objectives at Courcelette in September, 1916. This can still be considered a victory in light of the appalling casualties incurred by the French and British from July to November, 1916. Passchendaele, on the other hand, was even more disastrous for the BEF. By the fall of 1917, the Canada Corps had established themselves as an elite force following victories at Vimy Ridge, Lens and Hill 70. Despite 16,000 casualties, the Canadians succeeded in capturing Passchendaele in two weeks; something the British could not do in two months. For more information see the official history by G.W.L. Nicholson: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919 (Ottawa, 1964). Canada's military successes are also addressed by Bill Rawling's Surviving Trench Warfare, and Daniel Dancock's Legacy of Valour. |

|

5 |

Bill Rawling: Surviving Trench Warfare (Toronto, 1992). p.81-86. |

|

6 |

NAC, MG30E300/19, Army Summaries - The Somme, Jan-Dec. 1916, Short Notes Obtained from Units in the Somme Area'. p.1. |

|

7 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4146/8/9, '2nd Division Notes From Fighting on the Somme' |

|

8 |

NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers, 'Chapter VII - Sniping and the Organisation of Sniping in Open Warfare', p.4 |

|

9 |

Rawling: Surviving, p.98. |

|

10 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/3867/107/3, 'Notes and Suggestions - Training of Snipers in Rest, 05/24/1916', p.1. |

|

11 |

Griffith: Battle Tactics, p73. |

|

12 |

Rawling: Surviving, p48. |

|

13 |

Ibid., p27. |

|

14 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4135/22/4, 'Notes on a Conference of Scout and Sniper Officers, 06/02/1917', p3; NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers - 'Chapter VIII', p3. |

|

15 |

NAC, RG9IIIC3/4015/29/4,'1st Division Operations: Passchendaele, Section I, 1917', p6. |

|

16 |

Griffith: Battle Tactics, p77. |

|

17 |

NAC, RG41 /v .ll, 'CBC Interview - In Flanders Fields with L.R. Fennel, 27th Bn.', p7; NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers - 'Chapter IX - Sniping in Trench Warfare',, pi. |

|

18 |

Ibid., p1. |

|

19 |

Herbert McBride: A Rifleman Went To War (Mt. Ida, AK, 1987), p333. |

|

20 |

N.A.D. Armstrong: Fieldcraft, Sniping and Intelligence (Aldershot, 1940) p28-29. |

|

21 |

G.W.L. Nicholson: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919 (Ottawa 1964) pl70-171. |

|

22 |

Ian Skennerton: The British Sniper (London 1984), p67. |

|

23 |

NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers, 'Chapter VIII' p3. |

|

24 |

Hesketh-Prichard: Sniping, p27. |

|

25 |

NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers - 'Chapter XV - Snipers' Posts, Observation Posts, Loopholes and Hides', pl5. |

|

26 |

Hesketh-Prichard: Sniping, p110. |

|

27 |

NAC, MG30E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers - Chapter IX, p1. |

|

28 |

NAC, RG9 III D3/4912/War Diary of PPCLI: 'Narrative of Operations - August 25-29,1918', p2. |

|

29 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4015/29/4: '1st Division Operations: Passchendaele, Section 1,1917', p6. |

|

30 |

McBride: A Rifleman, p338-339. |

|

31 |

Ibid., p340. |

|

32 |

NAC, RG9 III D3/4912, War Diary of PPCLI, p2. |

|

33 |

Ibid., p3. |

|

34 |

CANADA, Veterans Affairs: Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields (Ottawa, 1993), pl2. It has been argued that Norwest was one of the best marksmen on the Western Front. Possessing all the true qualities of a sniper, he amassed 115 kills with the 50th Bn. before being killed in August 1918. |

|

35 |

NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers - 'Chapter IX - Sniping in Trench Warfare, p2. |

|

36 |

CANADA, Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, 1918, Sessional Paper No.27 (Ottawa 1918), pl4. Paudash was also recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal for saving an officer's life on the Somme, 1916. |

|

37 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4052/ 21/ 2, '10th Bn. to HQ 2nd Inf. Bde., 11/20/1917'. |

|

38 |

Nicholson: C E F, p333-338. |

|

39 |

Rawling: Surviving, p169. |

|

40 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4135/22/4, 'First Army to Canadian Corps, 2nd Division & 6th Inf. Bde., 06/10/1917'. |

|

41 |

Ibid. |

|

42 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4069/11/6, '8th Bn. to 2nd Division HQ, 01/14/1919'. |

|

43 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4192/15/3, '43rd Bn. Cameron Highlanders of Canada to 6th Inf. Bde., 01/16/1919'. |

|

44 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4095/3/36, '27th Bn. to 6th Inf. Bde., 01/11/1919'. |

|

45 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4095/3/36, Nth Inf. Bde. to 2nd Division, 01/15/1919'. A perusal of this file will show a number of positive responses to the use of snipers in open warfare, from battalion to brigade level. |

|

46 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4095/3/36, '5th Inf. Bde. to 2nd Division HQ, 01/13/1919'. |

|

47 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4095/3/36, '31st Bn. to 6th Inf. Bde., 01/10/1919'. |

|

48 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4192/15/3, '9th Inf. Bde. to 3rd Division, 01/18/1919'. |

|

49 |

NAC, MG30 E2/v.l, N.A.D. Armstrong Papers, 'Open Warfare', p.5. |

|

50 |

NAC, RG9 III C3/4192/15/3, Nth Inf. Bde. to 3rd Division, 01/18/1919'. |

|

51 |

Rawling: Surviving, p215. |

|

52 |

N.A.D. Armstrong: Fieldcraft, pv. |

|

53 |

Ibid., pv. |

Featured photograph of Canadian war hero and First Nations activist Francis Pegahmagabow. Photograph was taken shortly after World War I. Public Domain.