Cecil Patrick Healy: the only Australian Olympic Gold medalist to die in war KIA 29 August 1918.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Cecil Patrick Healy: the only Australian Olympic Gold medalist to die in war KIA 29 August 1918.

Cecil Patrick Healy - the only Australian Olympic Gold medalist to die in war – was a prominent figure in the swimming world in Australia and beyond, for more than 15 years. An early proponent of the new crawl stroke and the side breathing technique, he contributed articles to the press about swimming and surf-bathing.

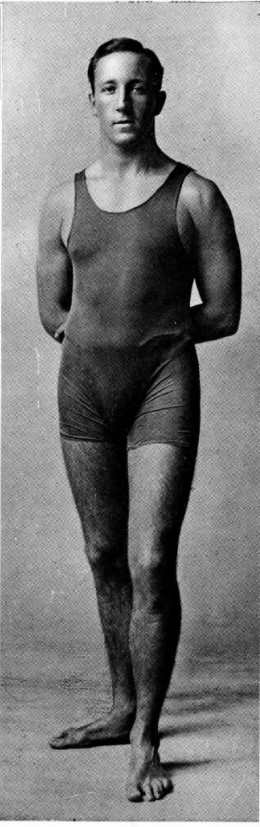

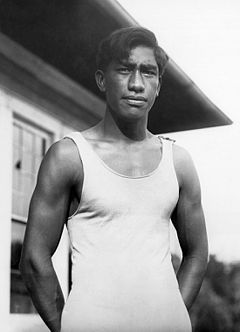

Above: Cecil Healy pictured in 1906

Cecil was born in Darlinghurst, Sydney on 28 November 1881, the son of a barrister. The family moved to the rural town of Bowral where Cecil received his primary education. He later would attend St. Aloysius College in Sydney. His first public appearance as an amateur swimmer would be in 1895, when he won a silver cup for a sixty six yards handicap race in Sydney. Following this, he made many appearances for the East Sydney Club, steadily improving his performances.

In 1906, he was sent to the 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens when he came third in the 100 metre freestyle. After the Games, he toured Europe giving many Europeans the opportunity to see the crawl stroke. He also competed in Hamburg, winning the Kaiser’s Cup and in Britain, winning the 220 yards British Championships.

Cecil had returned from Europe to Australia too late for the 1907 season and was unable to secure funding to enable him to attend the 1908 Games in London. That year, he won the 110 yard freestyle in the Australian Championships, also winning at this distance in 1909 and 1910, but losing the title in 1911.

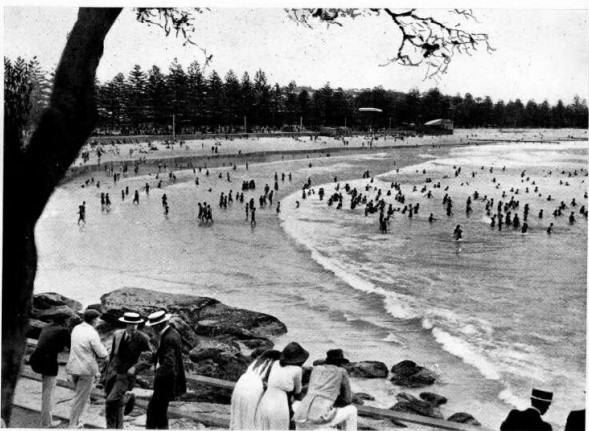

Healy was also a proponent of surfing and life saving and became a life guard at Manly beach.

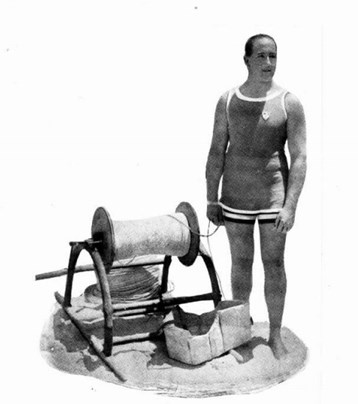

Above: surfing at Manly Beach and Cecil with life saving equipment

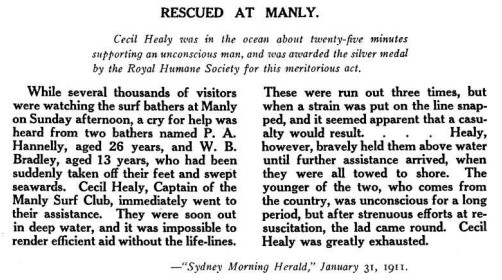

In 1911, he was awarded the Royal Humane Society’s Silver Medal and also a Certificate of Merit from the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society of New South Wales after a particularly difficult rescue in the summer of 1911, described in numerous letters to newspapers as the most meritorious rescue and resuscitation of the swimming season.

Above: the newspaper account of a rescue by Healy

Cecil qualified for the 1912 Olympic Games in which Australia and New Zealand sent a combined Australasian team to Stockholm. Competing in the 100 metre freestyle, he was beaten into second place and the Silver medal by the American swimmer Duke Kahanamoku, after what was described as one of the greatest acts of sportsmanship in Olympic history.

Above: Duke Kahanamoku – 100 metres Gold medalist in 1912

When the US team, including race favourite Duke Kahanamoku (who had clearly demonstrated in an earlier round that he was the fastest swimmer),was disqualified from the event after failing to turn up for the semi-finals because of confusion about the race start time, Healy refused to swim without Duke.Healy successfully protested until the Olympic Committee relented and the American swimmer and his countrymen were permitted to compete. Kahanamoku went on to win the gold medal, later declaring that Healy was “the true Olympic champion”. Healy went on to win a Gold medal in the 4 x 400 metres freestyle.

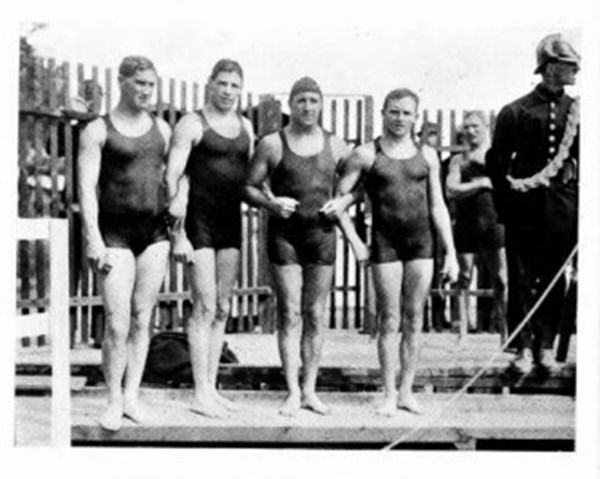

Above: the Gold medal winning team in the 4 x 400 in 1912. Healy is second from the right.

After the Games, Cecil again toured Europe, winning a number of races. As part of his tour, he visited Germany, where he was much impressed by the military precision in which the country’s railways operated. He would later write an almost prophetic article in which he remarked:

“It all prompts the thought that when the order is given for her army to march, Germany’s battalions will move swiftly and surely whithersoever they are directed without hitch or hindrance”.

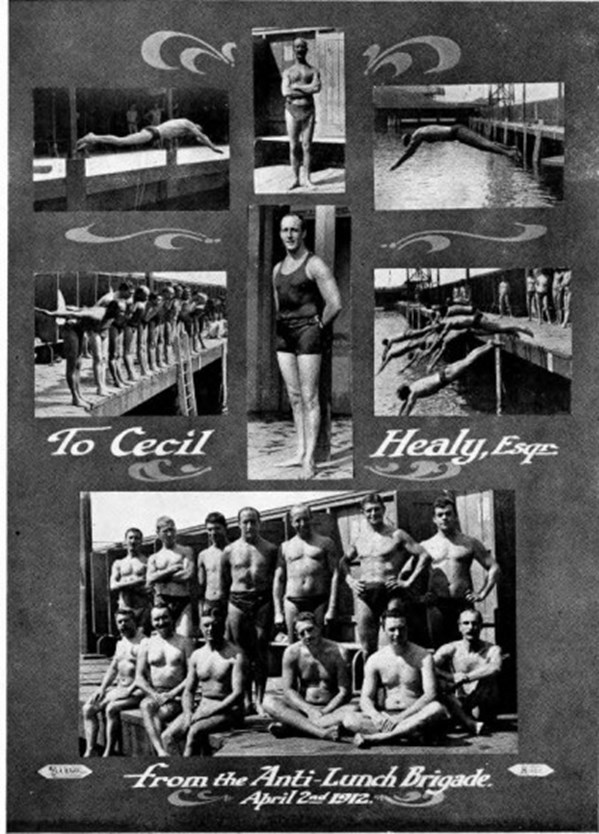

Before the war, Cecil continued to play a prominent role in swimming circles in Australia and was a regular contributor to the press on swimming matters. He also established a lunchtime swimming group which for a number of years attracted businessmen to the Domain Baths in Sydney. His ‘day job’ was that of a commercial traveller.

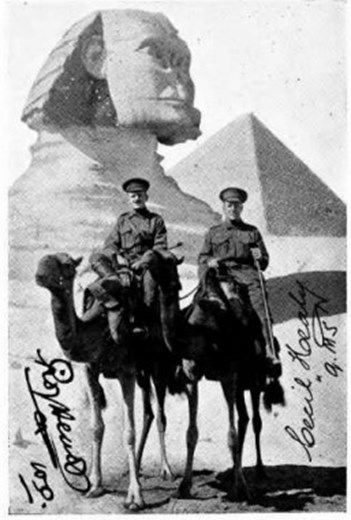

After the outbreak of war, Cecil enlisted in the A.I.F. in September 1915, serving initially as a Quarter Master Sergeant in the A.S.C. in Egypt. Cecil would later write that one of the first things he did in Egypt was to make enquiries as to whether there were any bathing facilities in the neighbourhood. Based in a camp on the Nile his immediate thought of the river was ‘how bonzer for a dip’ but he discovered that it was ‘out of bounds’.

Above: Healy in Egypt

Cecil left Alexandria in March 1916 for France, where he joined the 19th Battalion. In December 1917 he was sent to Cambridge to be commissioned.

Above: Cecil in Cambridge on Anzac Day 1918

After training in Cambridge and in France, Cecil joined the 19thSportsman’s Battalion in midJune1918. He was killed in action on

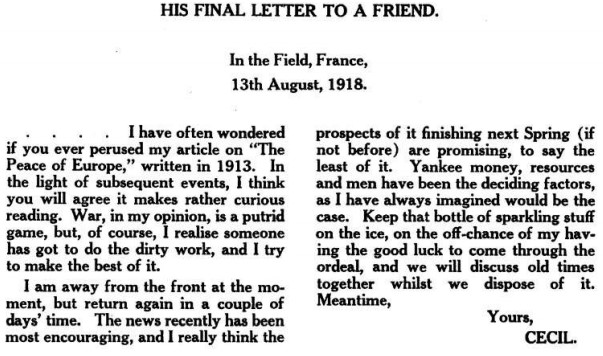

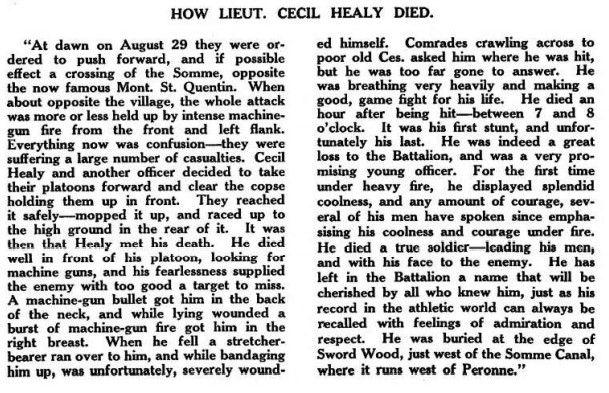

His last letter to a friend was later published:

Above: Cecil’s last letter and a report on his death

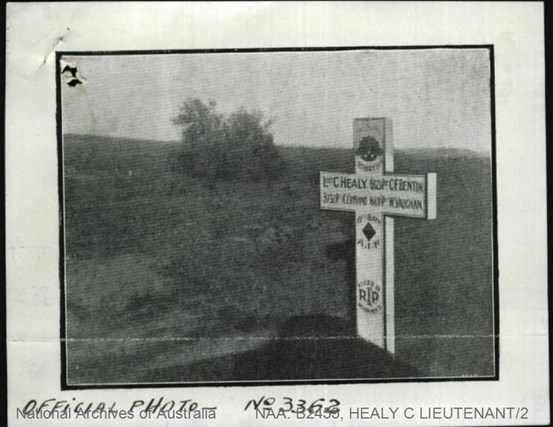

His grave was an isolated one which was later relocated to Assevillers New British Cemetery.

Above: Cecil’s original grave near Peronne. Photo in Service Record and Assevillers New British Cemetery where he is now buried. Photo - CWGC

On hearing of his death, Major Syd Middleton, a former Wallaby rugby union captain who had been Healy’s commander, wrote:

“By Healy’s death, the world loses one of its greatest champions, one of its best men. Today, in the four years I have been at the front, I wept for the first time”.

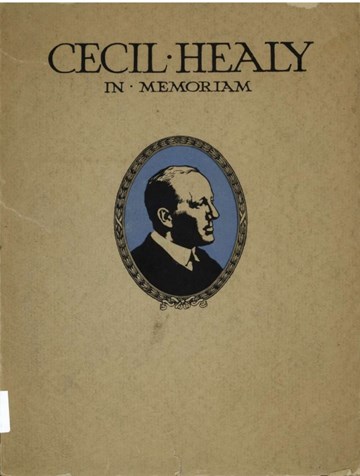

In 1920, a 48 page pamphlet was produced to record his achievements.

A statue was later erected in Assevillers.

Above: Statue of Cecil Healy in the village of Assevillers, Picardy, dedicated on 1 September 2018. Photo – Veteran Sport Australia

Above: Cecil Patrick Healy

Article by Jill Stewart Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Sources:

Cecil Healy – In memoriam – pamphlet produced in 1920. National Library of Australia

The Extinguished Flame : Olympians to die in the First World War – Nigel McCrery - 2016