Everard Wyrall (1878-1932): Military Historian

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Everard Wyrall (1878-1932): Military Historian

Last April [2021] I was asked to supervise a Wolverhampton University MA dissertation on 1/7th Northumberland Fusiliers. The battalion was in 50th (Northumbrian) Division TF, so before doing anything else I consulted my copy of the divisional history by Everard Wyrall. And then something happened that might have happened at any point in the past forty years. I said to myself ‘who on earth was Everard Wyrall?’ Actually, I might not have said ‘on earth’.

I decided to consult Professor Google.

This produced a few bits and pieces, some of which turned on further investigation to be wrong. But the lack of information was enough to intrigue me. The next step was to consult Professor Simkins. This made me realise the depths of my ignorance. Until speaking to Peter I don’t think I had ever heard anyone say the name Wyrall. Peter pronounced it ‘Wirrall’. Until speaking to Peter I don’t think I had ever heard anyone say Wyrall’s name. I had always pronounced it ‘Wye-rull’, which I later discovered from Celia Hyde, Everard's great niece, is correct. This is the way Everard’s sister Daisy insisted it was pronounced. Other than this, Peter didn’t know any more than I or anyone else did for that matter.

Who was Everard Wyrall? How come he wrote so many divisional and regimental histories? When I began to think about him nothing really came to mind. I couldn’t really get past his forename, with its echoes of Larry Grayson's imaginary friend.

I had no idea who he was, what his vital dates were, what his military experience was (if any), how he came to be the ‘author of choice’ for so many divisions and units, what his working methods were. I am not sure I have advanced very far, but it is clear that he was not ‘posh’, not really ‘officer class’ at all, a man of a very different stripe from the other major names among post-war formation and unit historians: C.T. Atkinson(1); C.H. Dudley Ward(2); Cyril Falls(3); F. Loraine Petre(4); and H.C. Wylly(5).

Who Was Everard Wyrall?

Reginald Everard Wyrall was born in Cheltenham on 8 June 1878. He was the second child of Charles Edward Norval Wyrall (1851-1928) and his wife Isabella Sophia Everard (1855-1941). Charles Wyrall described himself as a ‘photographic artist’. His father Edward (18??-18??) was an antiquarian, artist and translator and his mother, Maria (née Burton) (1827-92), was a music teacher. His older sister Evelyn was a photographic colourist and his younger brother Claude also became a photographer.

Charles Wyrall began work as a portrait photographer in Southampton at the age of 18. After a somewhat peripatetic existence, he settled for twenty years in Aldershot, ‘home of the British Army’, which may be significant for Everard’s subsequent career. Apparently, his portraits of soldiers in dress uniform are ‘collectables’. Everard Wyrall’s mother’s background was much less artistic. She was the daughter of Thomas Everard, a commercial clerk, and Sophia Levy, daughter of Thomas Levy, a carter. Her father died when she was young and when she was twelve her mother married James Bunn (1840-1902), who kept the ‘Nag’s Head’ in Chelmsford, where Charles Wyrall set up his business after leaving Southampton.

Above: The Nag's Head, Chelmsford

Everard had six siblings. He had an older brother Eustace (1875-1957), three younger sisters, Daisy(1880-1942), Dorothy (1885-19??) and Phyllis (1898-1977), and two younger brothers, Vernon (1881-1971) and Cedric (1885-1915).Eustace and Vernon followed the family tradition and became photographers: Eustace married Alice Radley, daughter of a boat builder; Vernon married Alice Grills, daughter of a house decorator. Daisy married a ‘piano tuner, music dealer and repairer’, Phyllis a ‘furniture buyer’. Cedric was an ironmonger at Gammage’s department store in Oxford Street (ironmongery was a Gammage speciality).

Above: Gammage’s department store in Oxford Street

He was briefly in the 6th London Regiment TF (London Rifle Brigade) before emigrating to New Zealand to be a farmer. He volunteered for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in August 1914 and was killed on the Gallipoli peninsula in May 1915.(6) The Wyrall family were, in short, a solid, commercial middle-class family.(7) When I set out to find Everard Wyrall, I don’t know what I expected to find, but I don’t think it was this.

Education

According to his entry in Who’s Who Everard Wyrall was educated ‘privately’ at Ryde House School, Ripley, near Woking, in Surrey, and at Schorne College, North Marston, Buckinghamshire.

Above: Ryde House School, Ripley, near Woking

Above: Schorne College, North Marston

I haven’t been able to discover much about Ryde House School, but Schorne College looked as though it might have provided a source of useful military connections for a future regimental historian. On further inspection, this turned out to be doubtful. Schorne College was founded in the 1870s by the Vicar of North Marston, Dr Samuel James. James claimed that the boys who boarded there were from ‘affluent families from all over the country and abroad, the sons of aristocrats, clergy or senior military officers’. The only evidence that Everard Wyrall attended Schorne College comes from his entry in Who’s Who. The information in such entries was provided by the persons invited to contribute them. They are often unreliable, both in terms of what they say and what they don’t say, though this is often revealing. I have found over the years that the ‘education’ entry is one of those most likely to be misleading. Wyrall was born in June 1878. If he had been educated at Schorne this was likely to have been between the ages of 8 and 18, 1886 to 1896. He is not in the 1891 Census for Schorne College, which is the halfway point.(8) During this period, his father was a photographer in Aldershot.

Above: A family portrait supplied by Wyrall's Great Niece, Celia Hyde. It is believed Everard is third from left, back row.

Wyrall was definitely not the son of a clergyman or a ‘senior military officer’ (whatever rank that starts at). I examined the family backgrounds of boys who were at the school in the 1891 and 1901 Censuses and they were far more modest than Dr James claimed. The pupils did not come from the social elite and their time at the school did not propel them into it in later life. A lot of the boys were at the fag end of large families. My historian’s instinct tells me that the number of siblings is significant, but I don’t know why. A large number of the boys also emigrated in later life. Schorne College, far from being an elite educational establishment, was a run of the mill proprietary school.(9)

Marriage(s)

Wyrall married twice. His first wife was Bertha Maria Strother (1883-1969), a fellow journalist.(10) They were married on 5 August 1911 at the church of St Clement Danes. The marriage lasted until 1920, when Bertha initiated divorce proceedings.(11) She first petitioned for the restitution of her conjugal rights. When I read this, being then unfamiliar with divorce case files, I thought ‘what a rotter, he abandoned his wife’. On reflection I concluded that the marriage had ‘broken down’. At this time women, but not men, had to establish two grounds for divorce. The petition for reconstitution was the first step. Once the petition was allowed, but not acted upon by the respondent, the petitioner could move to the second step, which was usually to petition for divorce on the grounds of adultery. This is what Bertha did. Wyrall did not contest the petition, but he (probably) hadn’t committed adultery either. As male adultery did not carry the same stigma as female adultery, he did the ‘decent thing’ and set up the appearance of adultery by booking in to a hotel with a woman while under the surveillance of Bertha’s solicitors. Even so, Wyrall soon remarried on 28 November 1921, seven days after his divorce became final.(12). His second wife was Marion Zeigler (1889-1979), a nurse.(13) They were still married at the time of his death. They had a son, Peter, who was born on 11 September 1922. (14) Marion did not remarry after Wyrall’s death.

Military Experience

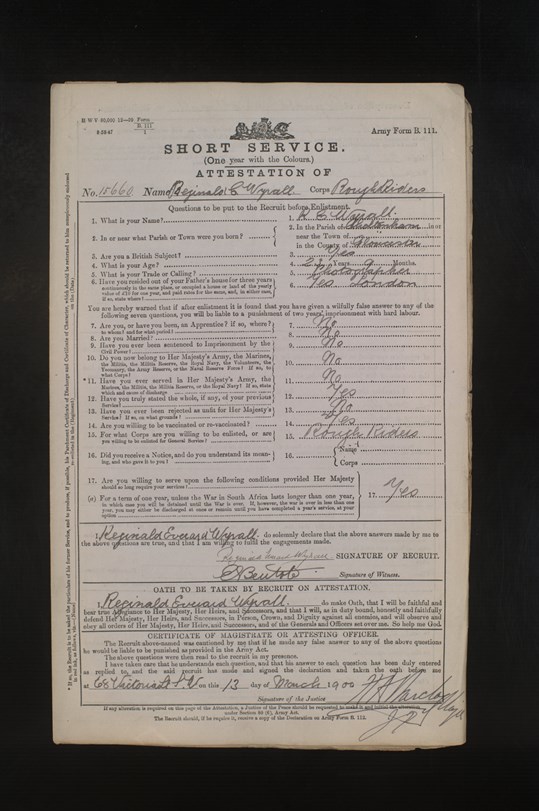

Wyrall’s first military experience was as 15660 Private, 20th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry (Rough Riders) during the South African War.

Above: Badge of the 20th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry (Rough Riders)

He attested on 13 March 1900. His age was ‘23 years 9 months’, occupation ‘photographer’, height ‘5 feet 9 inches’, weight ‘148 lbs [10st 8lbs]’, complexion ‘fair’, eyes ‘blue’, hair ‘flaxen’. He had a black scar inside his left ear. The battalion deployed after only a month’s training and its companies (72nd, 76th, 78th and 79th) posted to separate formations. Wyrall appears to have been in the 78th Company. He served in Cape Colony and the Orange Free State. It is not apparent why he returned home when he did. He was discharged, at his own request, on 30 November 1900 after a total of 263 days service, slightly over half of which were spent at home. He had no further military service until 1916, when he enlisted in the 28th (County of London) Battalion London Regiment TF (Artists Rifles), which operated as an Officers Training Corps.

Above: The Artists Rifles were originally the 20th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers

He was discharged to a commission on 25 October 1916. On his Attestation Form, he expressed a preference for infantry service, but his commission was in the Army Service Corps.(15) This is understandable. He was 38 and had the sort of literary skills prized in an administrative corps.

Temporary Second Lieutenant R.E. Wyrall arrived in India on 5 January 1917, attached to the Indian Supply & Transport Corps.

Above: Members of the Indian Mule Corps with their animals about to embark at Egypt for Gallipoli.(AWM A02299)

He was promoted to Lieutenant on 26 April 1918. He had quite a lot of ill health and was hospitalized from 6-15 June 1919 suffering from tonsillitis and debility.(16) He relinquished his commission ‘on completion of service’ on 28 October 1919 and retained the rank of Lieutenant.

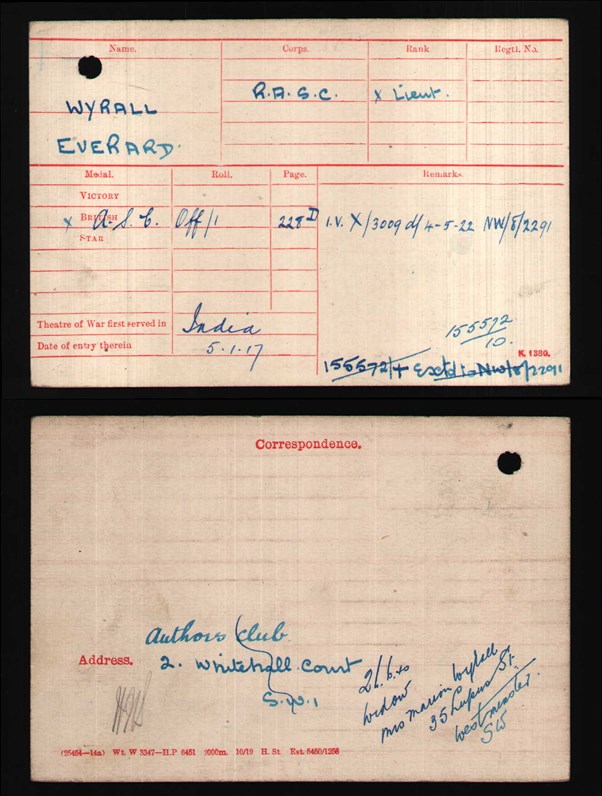

Above: Wyrall's Medal Index Card

Wyrall was awarded the India General Service Medal with three clasps, Afghanistan NWF 1919, Mahsud 1919-20 and Waziristan 1919-21.(17)

Above left: India General Service Medal with three clasps

Pre-War Career

Wyrall’s employment history prior to his enlistment in 1916 was varied: photographer; entrepreneur; teacher; journalist; author. When he attested for the Imperial Yeomanry in 1900 he stated his occupation as ‘photographer’. This continued to be his occupation for some time. His discharge from the Imperial Yeomanry did not terminate his connection with South Africa. He returned and lived there from 1901 to 1903.(18) It is presumably during this period that he ‘edited and owned the first photographic paper (The Camera) printed and published in South Africa’.(19) His Who’s Who entry then goes on to state that he became a ‘sub-editor on Fleet Street’, omitting mention of his time as a schoolmaster. Kelly’s Directory of Buckinghamshire (1907) lists him as ‘Assistant Master, Schorne School’, where he appears to have taught drawing. He had views on how children should be taught to draw. He published an article in the July 1908 edition of Pearson’s Magazine supporting a new theory of the art of drawing advocated by the Royal Drawing Society. This contended that children should be encouraged to draw what they see in their own way and not be restricted by ‘hard and fast rules’.(20) In the 1911 Census he was living in London (1 Plowden Buildings, Temple) and was recorded as a journalist.

Above: Plowden Buildings, Temple

In his 1916 Attestation Papers he described himself as an ‘author’.

Above: Wyrall's attestation papers.

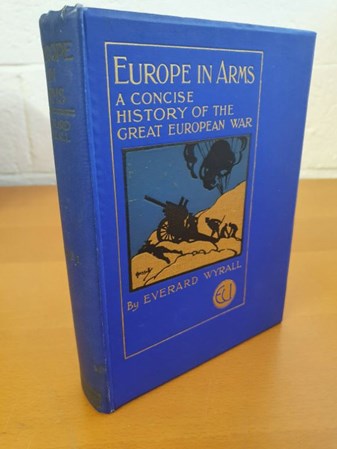

This statement rested principally on two things: his pamphlet, The Spike (1910), and his book, Europe in Arms: A Concise History of the Great European War Volume 1 (London: Bertram Wright & Co., 1915).(21)

Above: Europe in Arms:

The Spike was based on articles published in the Daily Express in 1908. Wyrall had gone ‘undercover’ (not very convincingly, apparently) to investigate the casual wards of workhouses,‘donning rags … breaking stones and picking oakum’, to see how the State treated the down and out.(22) He also investigated the provision for the poor made by the Church Army and the Salvation Army and defended their records for ‘doing good’.(23)

Inter-War Divisional, Regimental and Battalion Histories

Thirty-seven divisional histories were published between the wars: eight Regular divisions (including the Royal Naval Division); thirteen TF; and sixteen New Army. Wyrall wrote four of them – the 2nd (1921-22), the 19th (Western) (1932), the 50th (Northumbrian) TF (published in 1939, seven years after his death) and the 62nd (2nd West Riding) TF(1924) – one more than anyone else.(24)

In addition to these, he wrote seven regimental histories, a battalion history and a RFA howitzer battery history.(25) His nearest competitor was H.C. Wylly, who wrote five regimental histories and four battalion histories.

All Wyrall’s formation and unit histories appear to have been commissioned. The key to his career as a military historian is his first commission, the two-volume history of 2nd Division, published in 1921-22.(26) Once that commission was successfully fulfilled he was off and running. How Wyrall’s name emerged as a potential author is unknown and, perhaps, surprising. Six of the eight Regular divisional histories were written by former officers of their respective formations. The two exceptions were the 2nd Division and the 7th Division. The author of the 7th Division history was C.T. Atkinson, Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford University’s first lecturer in military history, who had several major publications to his name and had spent the war on the Historical Section of the General Staff. Wyrall did not have a university degree. He was neither a professional soldier nor a professional scholar. He had not served on the Western Front and had only one relevant (military history) publication. He had no connections with 2nd Division or with the divisional history’s leading progenitors, who appear to have been its former GOC, Sir Cecil Pereira, and its former GSO1, Lieutenant-Colonel (later General Sir) Charles Deedes, both of whom read and approved Wyrall’s text, or with any other senior military personnel.

It is therefore really quite difficult to see how the committee responsible for the 2nd Division’s history came up with the name of Everard Wyrall,(27) but once they did Wyrall’s principal ‘selling point’ would have been the history of the Great War he published in 1915.This was a grandiose undertaking. It was to be a multi-volume history written while the war was being fought, but it was abandoned – not surprisingly perhaps – after the publication of the first volume, whose 194 large format (24.5 cm x 17.5 cm) pages cover only the period from the Austrian Note to Serbia (23 July 1914) to the ‘repulse of von Kluck and the first British offensive’, roughly 10 September 1914. The book’s twenty-four chapters cover not only the fighting on the Western Front, but also the war on the Eastern Front, the war at sea and the war in the air. The book is illustrated and has several maps. The text is based entirely on ‘the official despatches, communiqués, and reports of eye-witnesses’ and ‘where dealing with matters which cannot be correctly termed “hostilities”, I have drawn upon unquestionable sources of information’. Wyrall’s dedication to ‘facts’ and to ‘narrative’ became the hallmark of his subsequent writing.

Wyrall elaborated on his methodology for writing formation and unit histories in an article for the Army Quarterly in 1923.(28) The article was not only a description of Wyrall’s working methods but also a set of prescriptive guidelines for future authors. His approach has been splendidly analysed by Professor Keith Grieves.(29) ‘For Wyrall,’ wrote Grieves, ‘historical method entailed standardised accounts of operations comprising intention, objective, disposition of forces, artillery, medical and supply arrangements, attack and results, but apparently with no evaluation of the whole process.’ Wyrall’s histories were to be ‘non-judgmental and controversy free’. As a result of Wyrall’s influence, according to Grieves, divisional histories became increasingly formulaic and ‘military history was constrained to the close observation of movements on the battlefield where explanation of advance and retreat loomed large, but overrode other facets including morale, social composition and officer and men relationships’. These comments are not only perceptive but also fair.

In his article, Wyrall stressed the importance of ‘marshalling your facts and information before you begin to write’. This took him to the divisional and other War Diaries in the keeping of the Historical Section of the War Office, under the Official Historian Sir James Edmonds, whose help Wyrall often acknowledged. (30)

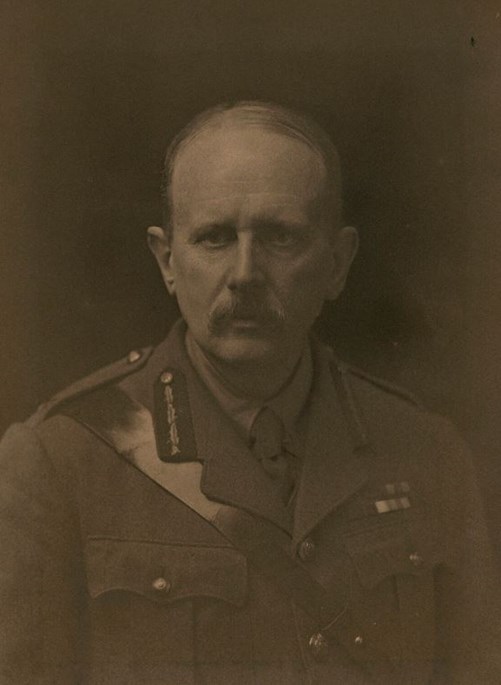

Above: Sir James Edmonds (National Portrait Gallery)

At this time, of course, War Diaries were not in the public domain and did not become so until they began to be released in 1965. Wyrall would then proceed to official despatches relative to the division, supplemented by personal diaries, letters and memoirs.(31) In his divisional histories with a regional focus and in his regimental histories Wyrall used the local press to canvass past members of the formations and units concerned for ‘diaries, trench maps or other useful information’. Such persons were encouraged to send materials to ‘Mr Everard Wyrall, c/o the Author’s Club, 2 Whitehall Court SW1’.(32)

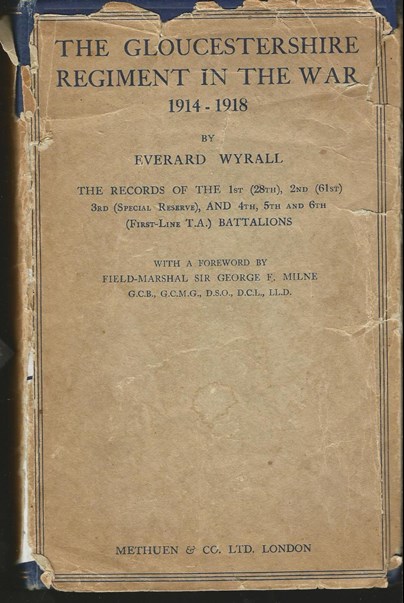

Wyrall stressed in his Army Quarterly article that the writing of Regimental histories was the most difficult. ‘Many regiments in the Great War,’ he explained, ‘consisted of at least twenty battalions spread over perhaps a dozen divisions all fighting on battle-fronts separated by many miles. In writing a Divisional history you merely keep one consecutive story going, but in writing the history of a Regiment you may have to keep the story of a dozen different divisions going at the same time, all dovetailed so that the reader does not notice that he is being taken here, there and everywhere up and down the whole line in a somewhat disjointed and hill-and-dale-fashion.’ The extent to which he succeeded in his Regimental histories is moot. Perhaps in the case of the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment he did produce an ’enthrallingly interesting narrative’ that gave the Regiment a ‘War Memorial more lasting than stone’, but his history of the Gloucestershire Regiment has been described by Joe Devereux as a ‘lost opportunity’ that details only a handful of the battalions that fought and ‘one of the poorest World War One regimental histories’.

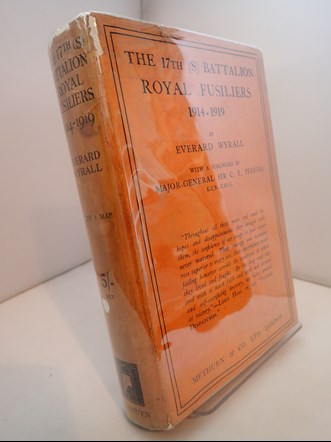

Wyrall’s only battalion history, that of the 17th Royal Fusiliers, was more suited to his narrative, storytelling style and is one of his most readable books.(33)

It has not proved possible to establish the financial arrangements under which Wyrall worked.(34) Whatever they were, they did not make him rich. He was sued for bankruptcy in 1932. The first petition was filed on 10 August, but no receiving order was made until 2 February 1933, an unusually protracted timescale, possibly occasioned by Wyrall’s death in December 1932.(35) His wife and son were left in straitened circumstances. Marion wrote to the Secretary, Officers Wives Department, War Office, on 11 July 1932, requesting assistance in ‘placing my small son Peter in a good school’. She was interviewed on 12 July 1932 and advised to apply for assistance to the Officers Association and the Imperial Service College. She was also ‘informed of the object of the Lord Kitchener National Memorial Fund Scholarships Scheme and of the minimum age of candidates’.(36) This was, of course, before Wyrall’s death. Interestingly, Marion wrote in her letter ‘I understand that my husband’s work has now finished with writing the war histories of several regiments which he has been engaged upon for several years’. Perhaps I am reading too much into the phrase ‘I understand’, but it seems to me to imply a degree of estrangement between Wyrall and his wife. She also used the phrase ‘my son’, rather than ‘our son’. This probably explains why she did not register his death and was not listed among his executors in the Probate Register.

Everard Wyrall died in King’s College Hospital on 22 December 1932. The cause of death, following a post mortem, was stated as ‘(a) Bronchopneumonia; (b) Stephylococcal Pyaemia’. ‘Pyaemia’ is ‘blood poisoning (septicaemia) caused by the spread in the bloodstream of pus-forming bacteria released from an abscess’. A post mortem would have been done because the doctors were in doubt about the cause of death. Just because he died in hospital, doesn’t mean that he had been receiving treatment there. He could have been rushed in and died quickly, even though the notice of his death in the Daily Herald stated that he had been ill for some time.(37) He was 54. The death was registered by his brother Vernon. He left £125 18s 6d. Probate was granted to his brothers.

J.M. Bourne

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.

Further Reading:

The Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division by Everard Wyrall

Notes

(1). Christopher Thomas Atkinson (1874-1964), Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, who almost single-handedly cultivated military history in the thin soil of Oxford University for many years. He was the son of Edmund Atkinson (1831-1900), Professor at the Staff College; educated Clifton College and Magdalen College, Oxford; married (1912) Emma Cosette ('Coo') Maurice (1874-1934), sister of Major-General F.B. Maurice (he of the ‘Maurice Letter’).Atkinson was attached to the General Staff Historical Section at the War Office during the war and was the man sent to France in 1915 to begin the collection of unit war diaries. Atkinson wrote a history of 7th Division and histories of the Devonshire and Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) regiments and of the South Wales Borderers. Whatever Atkinson’s merits as a historian, Sir James Edmonds did not rate him as an archivist. He left more than £36,000 at his death.

(2). Charles Humble Dudley Ward DSO MC (1879-1945), gentleman and author. He was the son of William Humble Dudley Ward (1849-1903), late 14th Hussars, and Eugenie Violet Adele Brett (1853-1958), the sister of Reginald Baliol Brett (1852-1930), 2nd Viscount Esher, eminence grise of Edwardian politics and chairman of the important Esher Committee (1904). His sometime sister-in-law, Freda Dudley Ward (1894-1983), was a mistress of the Prince of Wales. Dudley Ward was a novelist before the war. He was commissioned in the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, at the age of 35, but transferred to the Welsh Guards in September 1915, spending most of the rest of the war with them, ending in the rank of major. The six-volume manuscript journal of his service with the Welsh Guards is in the Imperial War Museum. He left his wife, Maidie Florence Frederica Cate Constance Thompson (1881-1937), in 1913 and refused to live with her again when she petitioned for restitution of her conjugal rights. He left just under £18,000 at his death.

(3). Cyril Bentham Falls CBE (1888-1971), military historian. He was the son of Sir Charles Fausset Falls (1859-1936), a landowner in Co. Tyrone. Educated at Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, Bradfield College and London University. He was a Clerk in the Foreign Office when the war broke out. He volunteered for military service and was commissioned in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and later served as a staff officer at the headquarters of the 36th (Ulster) Division and the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division TF. After the war he worked in the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (1923-39), was Military Correspondent of The Times (1939-45) and Chichele Professor of Military History at Oxford University (1946-53). He published his first book in 1915, Rudyard Kipling: A Critical Study. Between the wars he wrote a history of the Ulster Division, still much admired, a regimental history of the Royal Irish Rifles and a battalion history of the 21st Battalion London Regiment (Surrey Rifles). He left more than £25,000 at his death.

(4). Francis Loraine Petre OBE (1852-1925), Indian Civil Servant and military historian. He was the son of Hon. Edmund George Petre (1829-89), a Member of the Stock Exchange. Petrie was educated at Oscott College and was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1873. He joined the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in 1874, having been very successful in the demanding ICS examinations. He retired from the ICS in 1900 as Commissioner of Allahabad and devoted himself to military history, publishing five books on the campaigns of Napoleon. He spent the war years in the Finance Branch of the Ministry of Munitions. He left nearly £15,000 at his death.

(5). Harold Carmichael Wylly CB (1858-1932), professional soldier, author and editor. He was born in India, the son of Edward Michael Wylly (1817-62), of the Indian Civil Service, a Judge of the High Court of Accra. Educated Henley Grammar School, Wimbledon School and the RMC Sandhurst. He was commissioned in the Sherwood Foresters in 1878 and later commanded the 1st Battalion, seeing active service in Egypt, the North West Frontier of India and South Africa. He was a published author before the war, editor of the RUSI Journal (1913-23) and the RUSI’s Chesney Gold Medallist (1929). Wylly was second only to Wyrall in output. He left the modest sum of £1,400 at his death.

(6). Cedric Mornington Wyrall volunteered for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force at Paeroa in the North Island on 13 August 1914, arrived in Egypt on 4 December 1914, was promoted Lance Corporal on 1 January 1915, embarked for the Dardanelles on 12 April 1915 and was posted wounded, then wounded and missing, on 8 May 1915. His death on that date was confirmed for official purposes by a Board of Enquiry held at Ismailia on 16 January 1916. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Twelve Tree Copse Memorial, Gallipoli. He was 25 years old and unmarried.

(7). There were some family pretensions, however. Vernon Wyrall styled himself ‘Vernon Leslie De Wyrall’ in the 1911 Census, when he was living in Liverpool, and his first wife’s death record in 1967 is listed as ‘Alice C. De Wyrall’. The family (or some of them, at least) claimed Huguenot ancestry.

(8). He does appear in the 1891 Census, living with his family in Aldershot.

(9). There were attempts from 1905 onwards to sell Schorne College as a going concern, but these failed and it was closed in 1908. Dr James was found drowned in the Vicarage pond the following year. The College was eventually demolished by a local builder in the 1920s. I owe this information to The North Marston Story and am grateful to John Spargo and Su Chaplin for their invaluable help in this matter.

(10). Bertha Strother’s father, John Smurthwaite Strother, was a ‘gentleman of [modest] independent means’. She had a younger brother who was a clergyman and a younger sister who was a governess. Bertha styled herself in the 1911 Census as a ‘press representative’. Expert opinion tells me that this means ‘a reporter’. Bertha did not remarry until 1924. Her second husband was a solicitor.

(11). She initiated divorce proceedings on 11 October 1920. This was slightly less than a year after Wyrall completed his military service, during which he was in India for twenty months. The decree nisi was granted on 10 May 1921 and the final decree on 21 November 1921.

(12). Wyrall is described on his marriage certificate in 1921 as ‘Lieutenant Royal Army Service Corps (Retired) and Author’. ‘Retired’ is not strictly true. He had ‘relinquished his commission on completion of [the terms of his] service’.

(13). Marion Zeigler is a bit of a mystery.(Zeigler is the correct spelling of her name.)She was born on 7 November 1889 at 129 Westbourne Park Road, London. Her father’s name was recorded as Hans Ziegler [sic], commercial traveller, and her mother as Blanche Ziegler [sic] (formerly Woodlands), who appears to have been a dressmaker. Her marriage certificate to Everard Wyrall described her father as William Zeigler, ship owner, and her address as 89 Warwick Road, London. She qualified as a nurse at Bristol General Hospital (1917-20). She seems to have taken a serious interest in her profession and may be found from time to time in the pages of the British Nursing Journal. She was a nurse during the Second World War, when her address was the United Nursing Services Club, Cavendish Square. She died in London in 1979, aged 89. Marion emerges from the very fragmentary documentary record as a kind and caring person.

(14). Peter Cedric Everard Wyrall served in North Africa during the Second World War and appears not to have fully recovered from the experience. He committed suicide on 8 November 1958 by throwing himself into the Thames from Lambeth Bridge. He was 36. He had recently been made redundant from his job as a clerk and was due to enter hospital as an in-patient, having seen a psychiatrist. He had been under the care of his mother, but managed to slip away from her while she was in a shop. See Westminster & Pimlico News, 14 November 1958. (The front page of this newspaper recorded a litany of tragedies!)

(15). A comparison between his Attestation Form in 1900 and that in 1916 is instructive: in the sixteen year period he had lost half a stone and shrunk by two inches!

(16). He also seems to have suffered from chronic rhinitis.

(17). His India General Service Medal was sold at auction by Spink on 24 April 2008 for £280. He was also awarded the British War Medal.

(18). He embarked for Cape Town on board RMS Galician on 27 July 1901,and returned from Durban on board RMS Dunvegan Castle, arriving in Southampton on 11 July 1903.

(19). This enterprise was evidently short-lived and I have failed to find any bibliographical trace of The Camera.

(20). Preston Herald, 4 July 1908

(21). He also published a play, The Master’s Advent: A Prologue (1911), about Shakespeare (he was a keen Shakespearean). See his letter to the Pall Mall Gazette,5 February 1912.

(22). See Mark Freeman, ‘”Journeys into Poverty Kingdom”: Complete Participation and the British Vagrant, 1986-1914’, History Workshop Journal, 52 (2001), pp. 99-121. Exercises of this kind were relatively common. Wyrall was in some famous company, including Jack London and - later - George Orwell, who also published an essay with the title ‘The Spike’ in 1931. The quotation is from a brief obituary of ‘Captain Wyrall’ in the Daily Herald, in 1933, shortly after his death.

(23). See his letter to the Pall Mall Gazette, 22 May 1912.

(24). Wyrall’s corpus of divisional histories uniquely includes a Regular division, a New Army division, a first line Territorial division and a second line Territorial division. I have not succeeded in establishing why there was such a big gap between Wyrall finishing the 50th Division history and its publication. As David Tattersfield has demonstrated, Wyrall’s ‘two volume Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division, whilst the eighth longest in terms of number of pages, is arguably the most detailed as the division did not arrive in France until January 1917. It could therefore be said that this history has 239 pages per whole year of active service (or 21 pages per month of active service). The closest rival is that of the Guards Division. This division, formed in August 1915, has a 708-page history, which equates to 236 pages per whole year, or 18 pages per month of active service’.

(25). The regimental histories were of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (1932), the East Yorkshire Regiment (1928), the Gloucestershire Regiment (1931), the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment (1928), the Middlesex Regiment (1926), the Somerset Light Infantry (1927) and the West Yorkshire Regiment (1924). There is also the curious case of the Lincolnshire Regiment, which Wyrall allegedly researched and wrote, but which appeared under the name of Major-General C.R. Simpson. His battalion history was of the 17th (Royal Fusiliers) (1930) and his RFA battery history that of the 30th (How) Battery.

(26). 1921 was a bumper year, witnessing not only the publication of the first volume of Wyrall’s 2nd Division history but also histories of the 20th (Light), 33rd, 34th, 51st (Highland) and 56th (1st London) divisions. The 2nd Division was only one of two pre-war Regular divisions to publish a detailed history of its service in the Great War. The other was the 5th, written by Brigadier-General Arthur Herbert Hussey, who had been the division’s Commander Royal Artillery, and Major Douglas Stobart Inman, late Cheshire Regiment, who had served as an infantry officer with the division and later on the staff.

(27). The existence of such a committee is confirmed by Deedes’s letter to Pereira, dated 2 March 1919: ‘I really feel very flattered at you putting my name on the Committee on the Divisional History.’ See Edward Pereira, Spencer Jones & Michael LoCicero, eds., Catholic General: The Private Wartime Correspondence of Major-General Sir Cecil Edward Pereira, 1914-19 (Warwick: Helion, 2020), p. 425.

(28). Everard Wyrall, ‘On the writing of “Unit” war histories’, Army Quarterly, (July 1923), pp. 386-90. I am indebted to John Pearce (Senior Librarian RMA Sandhurst) for a copy of this article.

(29). Keith Grieves, ‘Making Sense of the Great War: Regimental Histories, 1918-23’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 69 (277) (Spring 1991), pp. 6-15. I am indebted to Professor Gary Sheffield for a copy of this article.

(30). See, for example, Wyrall’s ‘Foreword’ to his history of the Middlesex Regiment: ‘I should also like to thank Brig.-General J.E. Edmonds, C.B. C.M.G., Director of the Historical Section (Military Branch) of the Committee of Imperial Defence and his Staff for much valuable aid, without which it would have been impossible to write a regimental History of this magnitude.'

(31). Pereira was particularly generous in providing material from his personal diaries and wartime correspondence in the writing of the 2nd Division history, material that did not enter the public domain until 2020.

(32). See, for example, Yorkshire Post, 19 October 1920

(33). Sir Cecil Pereira wrote the Foreword to the 17th Royal Fusiliers’ history, commenting that it was a ‘matter of congratulation to the Battalion that their gallant deeds have been worthily told by Mr Everard Wyrall, an old acquaintance of the 2nd Division’.

(34). For example, despite the valiant efforts of Ian Riley, Clare Cunliffe, Colonel Robin Hodges and others, no paper trail relative to the financial arrangements for the writing of Wyrall’s history of the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment has been found. There is more work to be done here in relation to other of Wyrall’s histories.

(35). I am very grateful to Ian Marshall for his help and advice on bankruptcy proceedings during this period.

(36). Marion’s correspondence survives in Wyrall’s service file in the National Archives: TNA: WO339/76563.

(37). Daily Herald, 8 February 1933. This is confirmed by ‘A Note on the Author’ in the 50th Division history: ‘The History of the 50th Division was fated to be his last book, and his work on it was indeed a soldier’s last fight. When he engaged to write it his health was already causing grave concern, but his courage, conscientiousness never failed him. It is the simple truth that when the last sentence was written he closed his eyes and died.’

[I am pleased to acknowledge the help of Professor Stephen Badsey, Jagmaan Bakshi, Tom Bourne, Marcus Budgen (Head of Medals, Spink), Sue Chaplin, Clare Cunliffe (Curator, The King’s Regiment Collection at the Museum of Liverpool), Joe Devereux, Paul Handford, Su Handford, Tony Hearn, Andrea Hetherington, Colonel Robin Hodges, Rich Hughes, Simon Jones, Dr Michael LoCicero, Ian Marshall, Dr Stuart Mitchell, Dr Nicholas Perry, Terry Reeves, Ian Riley, Professor Gary Sheffield, Professor Peter Simkins, John Spargo (Chairman of the North Marston History Club), William Spencer and David Tattersfield.]