The Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division by Everard Wyrall

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division by Everard Wyrall

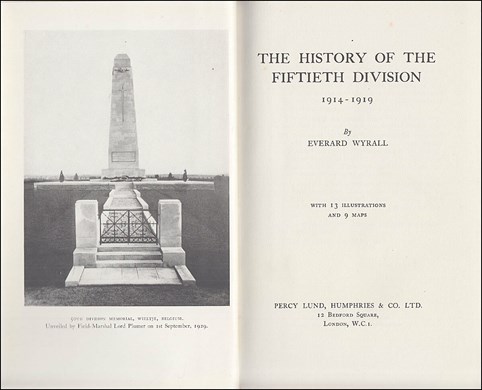

Depending on how one would define a Divisional History, approximately forty British Divisional Histories were published between 1919 and 1939.[i] Care does need to be exercised with this number, as certain titles listed by Dr Bourne are stories of sub-units[ii] or seemingly merely lists[iii] or cover only a brief period of the division’s war service.[iv]

Of the 39 Post War Divisional Histories that are not stories of sub units, lists or covering a short period of the division’s war service, there are 37 Divisions represented[v] in the list.[vi] The vast majority of these 39 Divisional Histories were written between 1919 and 1929,[vii] with the year 1921 having the greatest number of publications with eight histories coming out in that year alone.[viii]

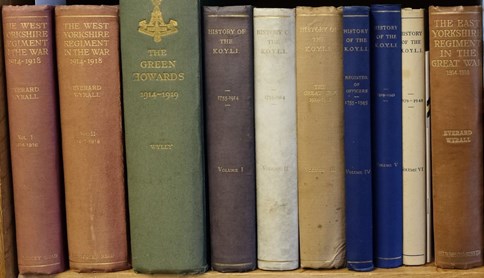

The 38 books[ix] in the following analysis were written by a number of individuals, however two authors between them accounted for seven of the publications.[x] Besides writing four divisional histories, Everard Wyrall also wrote Regimental Histories on a large scale, producing seven Regimental Histories,[xi] a Battalion History,[xii] and was seemingly planning to write the history of an RFA Battery[xiii] prior to his death.

C.H. Dudley Ward, whilst publishing three divisional histories, does not appear to have ventured into writing Regimental Histories unlike another prolific author, C.T. Atkinson who although only writing one Divisional History, also produced four Regimental Histories.[xiv]

Some of the histories can hardly be expected to be dispassionately written, with several of the books being written by men who held general officer rank within the division during the war.[xv]

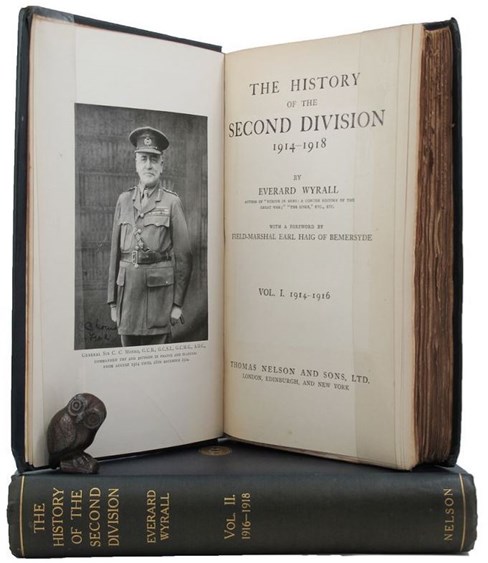

The Divisional Histories vary greatly in length, from less than 100 pages[xvi] to tomes of over 700 pages.[xvii] It is interesting that Wyrall wrote the longest Divisional History as well as the most detailed one in terms of pages in proportion to active service.[xviii]

An interesting analysis is possible of the types of division about which histories were written. A total of seven divisional histories were written for the twelve Regular British Army Infantry Divisions.

Of the 31 New Army Divisions formed (and included in this is the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division which had very similar characteristics to the “Kitchener” Divisions), a total of 18 histories were written. For the Territorial Force, thirteen divisional histories were written on twenty active service Territorial Divisions.[xix]

In percentage terms, 58% of both the Regular and New Army divisions had their divisional histories written[xx] but the Territorial Force achieved 65%.[xxi]

The explanation as to why there should be so much disparity between, for instance, the K1 divisions and the First Line Territorials is probably to be found in the pre-war and post-war periods. The Territorial Force, unlike the New Armies, had a pre-war and post-war existence. The Territorial Force was organised into County Associations, often headed by a member of the aristocracy. Such families would not only have had a sense of history but also the financial resources to commission histories of ‘their’ Territorial divisions.

Battalions in the New Army divisions were disbanded immediately after the war was over, and having no post-war existence were therefore reliant on motivated individuals who had either the money or the contacts to commission divisional histories.

It would be reasonable to expect that more than 58% of the regular divisions would have had divisional histories written; indeed with a proportion of these units having pre-war and post-war existence, one would have thought that they would have had a higher percentage than the New Armies. It should be noted that the 27th and 28th Divisions spent much of their war on the ‘unfashionable’ and largely inactive Balkan front. These two divisions had no divisional histories, and if they are therefore removed from the equation, we have seven out of ten divisional histories written for this group: a very similar ratio to the Territorial Force histories.

One of the most striking points of the divisional histories is the lack of any Cavalry divisional history. This may be due to the lack of opportunity these units had apart from fleeting chances at Cambrai in 1917, small unit actions during the 100 days and occasional dismounted action. Perhaps it was recognised that the Cavalry did not have a ‘good’ war on the Western Front, and the fact that this arm did well in Palestine is emphasised by the existence of a history of the 74th (Yeomanry) Division, which served in this theatre.

Some clues as to how these histories came to be written appear in the introduction to The West Riding Territorials in the Great War. Laurie Magnus indicates that another officer was unavailable, but Lord Scarborough (Chairman of the West Riding County Territorial Association) was pointed in the direction of Magnus who, presumably, was pleased to accept Scarborough’s commission.

Magnus’s book was published in 1920, running to over 300 pages, however the text stops at page 221, with the rest of the book given over to appendices. As these 221 pages cover the histories of two divisions, this book really falls into the ‘short’ category mentioned above. It is possibly for this reason a book on the 62nd Division was commissioned. Presumably the officers of this division felt their division, which by any standard had a much better reputation than the 49th,[xxii] deserved more than about 100 pages in a book with another unit, even if that unit was its First Line equivalent. By 1920, when Magnus’s book was available, Everard Wyrall had already had published the Regimental History of the East Yorkshire Regiment, and his 722 page History of the Second Division would have been in the final stages of completion. It is possible the knowledge that he could produce a book of such length led to him being commissioned to write the 62nd Division’s History.[xxiii]

Whilst it is not within the scope of this essay to investigate who commissioned the writing of The Story of the 62nd Division, it is possible to speculate that it was not the permanent members of the West Riding Territorial Force Association. This is because these individuals are listed by name in the first appendix in Magnus’s book (possibly as some form of acknowledgement that it was at their instigation the book was written) with Lord Scarborough also mentioned in the introduction. As outlined previously, it does ‘feel’ as though Wyrall’s book was commissioned as a reaction to Magnus’s; if this is the case, it is highly unlikely that the same group of men would have commissioned an ‘alternative’ history to the earlier work. A possible clue to one of the men behind Wyrall’s book appears in the third chapter of volume two. In this very short chapter Wyrall seems to go off at a tangent and for the first time go out of his way to write about the Divisional Artillery.[xxiv] Two pages into the chapter Wyrall contrives to mention the death of a specific officer, Lieutenant J.C. Massey-Beresford.[xxv] Whilst the mentioning of a specific officer in this way is not unique within the book, Wyrall only does this infrequently, and then only if the officer warrants a mention for some specific act; Massy-Beresford certainly does not, on the face of it, warrant such a mention. It is unlikely he was mentioned on a whim, and the fact that he was a young (regular) officer with well-connected parents suggests the possibility that his father may have been a driving force behind the writing of the book. There seems to be no other reason for the inclusion of the specific reference to this officer.

Wyrall’s approach to the Story of the 62nd Division is radically different to that of Laurie Magnus. In his book on the two West Riding divisions, Magnus clearly had to keep the detail to a minimum in order to cover two divisions; he also makes use of very basic maps, photographs and sketches, presumably by officers or men, of the landscapes they came across. There are even occasional cartoon drawings of Pelicans![xxvi] Overall, it is a very ‘accessible’ book to read.

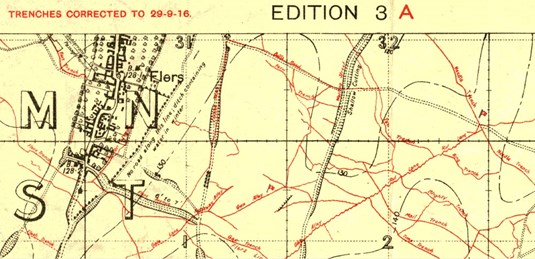

Wyrall by contrast seems to have set out to give as much detail as possible. Presumably this was part of his brief, as a reaction to the scant detail in Magnus’s book. Whilst there are photographs within Wyrall’s book, these are more formal than Magnus’s. Wyrall’s maps are significantly more detailed, to the point where they can be difficult to interpret.

In addition to providing detailed maps throughout the book, which runs to two volumes, Wyrall makes a specific point of giving map references. Whilst this is useful to a modern-day historian who has access to trench maps, it is difficult to imagine Wyrall being so far sighted as to write the book for future generations. Did he really hope or expect that trench maps, still classified as secret in the 1920’s, would at some stage in the future be made publicly available? Because of the excessive detail on the maps in the history, without access to trench maps, it is sometimes impossible to pin down the map references he gives on the maps within the book.[xxvii]

Why then did Wyrall insist on the use of map references? It can only be assumed that this was tolerated by, retrospectively authorised by, or specifically required by the committee instructing him. Whilst a modern day historian can (with the use of trench maps) gain a lot from this, it is nothing more than one can gain by accessing the War Diaries at the National Archives in Kew.

The above observation and other factors inevitably lead the reader to the question ‘For who is this book intended?’ Whilst it is less ‘old fashioned’ in its language than Magnus’s book, it is much less of an easy read than Magnus. Taking into account the fact that Wyrall’s book is much more detailed than that of Magnus, does this mean that Wyrall’s was intended for historians of the 1920’s and 1930’s? This seems unlikely, although he may have hoped that historians would gain something from it. Clearly a book purely for historians would not sell to the general public and the financial backers would therefore be left out of pocket. Is the book therefore intended for the general public? Again this is unlikely. Whilst the public may have been willing to purchase books about the recent war in the early 1920’s, it is unlikely they would have been happy to spend what would have been a significant sum on a two volume work about an obscure second line territorial division, no matter how good that division was. Was the book therefore aimed at former members of the division? It seems that this was the most likely audience with, presumably, Wyrall hoping that it would also have appeal to historians, and the backers hoping it would have at least some appeal to the general public. All of this does leave the modern-day historian having to work hard to get anything out of the book.

Several recent historians, including Jonathan Walker, Robert Woollcombe, AJ Smithers and Paul Greenwood have made use of Wyrall’s book.[xxviii] Walker does not acknowledge use of Wyrall in his bibliography, although he does source certain passages; the others in contrast do acknowledge Wyrall in their bibliographies. Smithers has the following to say about divisional histories: “…there is no substitute for the works of divisional writers…. it was almost a matter of luck whether a formation possessed somebody with the will and means to chronicle its doings…. they all contain information not to be found elsewhere.” One assumes Smithers excludes from this the war diaries.

Even bearing in mind that Wyrall’s book was not aimed at modern audiences, there are in the opening pages, sweeping generalisations that make a reader wince. It is surprising that a professional writer could make patronising comments along the lines of (describing the appalling conditions of the early spring of 1917): “…the stout Yorkshiremen were equal to the occasion; their hardy lives in the north of England had well fitted most of them for their tasks…” (page 32). Presumably the fact they were “thrifty and industrious” (page 1) also helped.

Clearly such writing was of no use to historians of the time, and is equally of no use now,[xxix] other than to show that a romanticised version of the north was being pedalled as recently as the 1920’s. Perhaps some readers were happy to naively accept this, but it is difficult to see this being accepted by old sweats of the division. A more generous interpretation of this style is that it was a book of its time as shown in ‘sporting’ footnote (3) on page 150.[xxx]

Another major criticism of Wyrall’s book is his lack of acknowledgement of sources and lack of bibliography. From the early pages onwards, Wyrall uses inverted commas for quotations from other sources, but simply sources these as “an officer of the division” (page 4) or slightly more specifically “one of the brigadiers” (page 7), but some quotations are not sourced at all (large section on page 5). The exception to this is his acknowledgements of Lt-Gen. Braithwaite who clearly contributed to the book.

Above: General Sir Walter Pipon Braithwaite

Perversely, however, this ‘rule’ is reversed on page 212 when he quotes at length from “the commander of ‘B’ Company” (of the 8th West Yorks (Leeds Rifles)). This officer is clearly identified one page earlier as Captain Burroughs.

Above: A Leeds Rifles shoulder badge

It would seem that Wyrall’s intention was not to specifically identify each time he made use of another author’s work, although he seems to be prepared to refer to the author the first time he used it. This is very evident in his footnote on page 24 when he attributes a quotation to Brig-Gen. AT Anderton, but without acknowledging the almost certainty that the passage used was from Anderton’s War Services of the 62nd Divisional Artillery. There are numerous examples of Wyrall seemingly lifting from, but not acknowledging Anderton, for instance, on pages 145 and 216. This is again demonstrated much later in the book when in the footnote on page 219, Wyrall hints at a book about the 2/20th Londons, but does not until page 11 of volume 2 actually refer specifically to the book.[xxxi] Such unwillingness to attribute sources is certainly unhelpful for modern day historians, as further reading of Wyrall’s sources is difficult to undertake when those sources are unknown.[xxxii]

Within Wyrall’s book there are constant references to ‘official despatches’. It would seem that in the 1920’s this is all that Wyrall had available to give him an overview of what was going on in the wider context of the Western Front. This is clearly a further limiting factor to the current value of the book, as the author did not have access to the wealth of information now available.

The most regular sourcing Wyrall undertakes within the book is to the War Diaries, with occasional comments.[xxxiii] Such references to the war diaries (when other references are very thin on the ground) does hint at Wyrall making a point to his readers. Perhaps he wished to make it clear that he had obtained access to still-classified documents that no other writer would be able to obtain. This must have been frustrating to contemporary historians, but following the declassification of these documents many years ago, it is no longer a point of significance.

Wyrall, as mentioned earlier, is careful to acknowledge Braithwaite’s help, but his treatment of subordinate commanders is inconsistent. He is almost sycophantic in his references to Brig-Gen. Bradford. Some other infantry brigade commanders get frequent references (although this does not extend to the artillery, which throughout only gets a cursory mention) however other infantry brigade commanders are either not mentioned at all[xxxiv] or are firmly swept under the carpet.[xxxv]

The lack of criticism of Brigadiers is extended to every other part of the division. It is clear that the 62nd Division was a very good division, but the fact that throughout the book Wyrall fails to highlight any shortcomings detracts from an informed opinion being formed as to the truly excellent reputation the division made for itself.[xxxvi] There is no criticism, for instance, of the division’s performance at Bullecourt in May 1917. Page 52 summarises the reasons for the failure and gives a clear hint that the tactics (laid down by higher formations) were wrong. This may be partly the case, and Bullecourt was a difficult operation, but to make no criticism whatsoever of the division devalues its later achievements.

This argument is supported by Cyril Falls who is quoted[xxxvii] as having only one criticism (of Wyrall’s book) “…the extraordinary change in the division between its arrival on the battlefield and the armistice hasn’t been fully brought out.” Falls’s statement is clearly pertinent, and is best shown at the end of the book on page 151 of volume 2. On this page Wyrall blandly states that the 62nd were the only Territorial Force division to enter Germany, but fails to make the point that the division was in any way an ‘elite’ unit.

As ever, there are occasional exceptions to the general lack of criticism mentioned above. On page 102 of volume 2, Wyrall explicitly states that “the frontal attack of ….the 2/20th Londons was a mistake” and goes on in a footnote to link the commanding officer of the battalion to this statement, therefore implying his error. Page 233 implies a criticism of the planning for an attack (“the absence of a creeping barrage was a curious omission”), and he confesses on page 16 of volume 2 that “results were disappointing” but, he adds “there was a limit to human endurance”. Possibly the most severe criticism that Wyrall implies but fails to fully expand on is the withdrawal of 2/7th Duke of Wellington’s on 26 March 1918 at Bucquoy. A historian studying this action, on reading this passage, is left with the feeling that there is certainly a story that has not been told.[xxxviii] This is a good example of a reader or historian having to work hard to get anything out of the book, and is one of a few ‘signposts’ to matters that are worth following up.

Not only is there a lack of criticism of units within the 62nd Division, but Wyrall also generally fails to make any criticism of neighbouring units (which is not the case when one reads war diaries!).[xxxix] Whilst we cannot expect a great deal of detail in a divisional history about neighbouring units, some comment or criticism would assist an understanding of the division’s success or failures if these were partly due to the division’s neighbours.

Any historian reading Wyrall’s book on the 62nd Division, believing he will obtain an understanding of the relative importance of the various sub-units is likely to be disappointed. Wyrall’s book is predominantly a book about the division’s infantry. He only occasionally makes reference to the artillery, and the amount of general detail falls a long way short of what should be included if the proper balance between the artillery and infantry is to be expected. Equally, little mention is made to the Royal Engineers, although possibly as an attempt at giving balance, an entire appendix (VI) is given over to the Report on Operations by the RE in the bridging of the River Selle. It is possible this rather strange appendix was added, together with Chapter 3 in volume 2 (dealing with the divisional artillery between 21 August and 6 September 1918) at the insistence of the supervising committee, as both the artillery chapter and engineers appendix do not sit comfortably with the rest of the book.

Other sub-units are given only passing references, and even more frustratingly, are not indexed. The Divisional Signal Company on page 151 and Trench Mortar Batteries on page 31 of volume 2 are given a fleeting mention; the Army Service Corps on page 217 and the RAMC on pages 218 to 219 are also mentioned. This is certainly not the place for any historian to go who wishes to read about small sub units in a division. Perhaps this is understandable bearing in mind the constraints under which Wyrall had to work, however there is also a great disparity in the coverage of the infantry battalions.[xl]

For all Wyrall’s inconsistencies in terms of sourcing and uneven coverage of units, any historian would reasonably expect Wyrall to be very accurate in his work. Even without a full comparison of the text to other sources, a surprising number of inaccuracies are readily apparent. These range from the minor typographical error in naming the village of Ytres (near Cambrai) incorrectly as Ypres,[xli] to the placing of the 4th Guards Brigade in the Guards Division instead of the 31st Division.[xlii] A more serious error still is the misnaming of a battalion within the division when describing a minor action in 1917.[xliii]

Wyrall also has some difficulty with the casualty figures, especially when one studies the appendices and compares the figures to those given in the text. This applies to both the officer casualties in Appendix 8[xliv] and the NCOs and men who also appear in this appendix but are separately tabulated at the end of the appendix.[xlv] He also manages to contradict himself on what would appear to be a straightforward point when he states in the text that a particular officer was “the first casualty” but another officer is listed in the appendix as having that dubious honour.[xlvi]

If a historian is trying to gain an understanding of the 62nd Division’s use of tactics, then reading Wyrall will not assist at all. The nearest he comes to this area is on page 94 when he attributes the division’s success at Cambrai in 1917 being due to tanks replacing artillery. Whilst use of tanks was innovative in this battle, the successes are arguably more due to silent registration of artillery than the mass use of tanks. Misleading comments such as these are likely to trap an unwary or amateur historian, which can only be corrected by a wide reading of a more modern analysis of the battle. Thankfully, there are few other passages in which Wyrall expresses his opinions about tactics, although there are other examples of him passing comments, which are probably taken from the war diaries (or operational reports within the diaries). This is particularly noticeable on page 15 of volume 2 when he describes the difficulties encountered in clearing a village, which had supposedly been taken by tanks. This is a very useful passage and does set out very clearly the problems that were probably encountered at this stage in the war when tanks were used. Presumably Wyrall must have found a useful report in the war diaries, as he is still undertaking the analysis of this attack three pages later (page 18 volume 2)! This is certainly an exception to the rest of the book which, generally, carries no analysis of operations.

Careful reading of certain passages does confirm modern-day understanding of the difficulties that were faced and how they were overcome,[xlvii] but this is only apparent if a reader is sufficiently well versed in the detail of the war to be able to spot them. Despite this, Wyrall does not really give an impression of the quickening tempo of the attacks from August 1918 onwards. Whilst modern day historians are well aware of this, perhaps those historians reading this in the 1920’s would have found it helpful to have this aspect made clearer. This failure to fully highlight the quickening tempo is probably a result of Wyrall’s reading of the dry and unemotive reports within the war diaries. If Wyrall (and other authors of his generation) failed to realise the true nature of what the British Army achieved[xlviii] in the final 100 days, it is not surprising that the myth of the ‘unbeaten’ German Army grew.

For all the criticism of Wyrall, he was no doubt under contract to produce a book that had to comply with the wishes of some sort of steering committee. He clearly had access to excellent primary sources (being the war diaries and personal diaries) and had to balance the use of these.

The modern historian with easy access to the war diaries, operational orders and reports on operations at The National Archives probably does not really need the detail that Wyrall gives. What would have been of more use to a modern historian is the anecdotes and small but interesting glosses that he sometimes adds.[xlix]

Subject to having freedom from the committee, he could have gone about producing the book in any number of ways. He could have written it from the point of view of the divisional commander or his subordinates. He could have attempted to write it referring only to the major set-piece battles, or made the chronology very even and given equal emphasis to each day, even if there was nothing to write about. He could have paid more or less attention to the geography, or the VC winners or the tactics, or explained in more or less depth what the division was doing in the wider context of the war. The book is a compromise of all of these options and this compromise must be accepted when studying the book. Clearly what one historian finds irrelevant, such as the names of individual soldiers, another would require in more detail.[l]

As set out earlier, the book was probably not primarily intended for historians in any case. If a historian is wanting to obtain an in-depth account of a particular battle, there is obviously little benefit in consulting a divisional history, even one as detailed as the one on the 62nd Division. The divisional history may give an overview of the battle, but Wyrall is not consistent in the amount of detail given.[li]

What really adds value for a historian is if one comes across an anecdote directly relevant to what is being studied.[lii] Possibly the reason for the general lack of these anecdotes[liii] is the fact that these were in plentiful supply in the 1920’s – every old soldier who was willing to talk would have numerous stories – in direct contrast to the information available in the War Diaries which was still classified. This is the exact opposite of the situation today, where the sources of anecdotes have effectively passed away with the majority of the old soldiers.

Wyrall’s Story of the 62nd Division is certainly of some use as background or to give an overview of the division if a historian is looking at a large number of divisions in a particular battle. The passages between the major battles are generally superficial, but this is obviously necessary so as to keep the book within a manageable length. To go into frequent detail about general trench holding operations[liv] would simply be repetitive.

Clearly Wyrall had to make decisions about what to include and what to exclude, although as previously mentioned, some influence may have been brought to bear by the book’s sponsors. For this reason the perceived historical value of the book will vary between historians, and it cannot possibly be everything to all men. As a general account, it is more detailed than virtually any other divisional history, but is still insufficiently detailed for most historians’ requirements. If, however, a historian is prepared to take time with the book, rewarding snippets or anecdotes can occasionally be found, and at the very least the appendices (particularly the ones listing casualties) can, if treated with care, be useful.

The worst failing of Wyrall is his uncritical approach to his subject, however bearing in mind the book was published in 1924 and 1925 and many of the participants were still alive, Wyrall, for that reason alone would have avoided wanting to offend or even attract litigation. Perhaps the strengths of divisional histories are that they set out to tell a story without being judgmental; certainly if opinions were to be expressed it could have opened the floodgates for readers who wanted contrary opinions to be aired. The lack of criticism may, inadvertently, have led to the later backlash against the war by other writers, but that, of course, is another matter altogether.

No doubt Wyrall’s book assisted many old soldiers to answer the question “Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?” - and it is for these men the book was surely intended.

Above: The Memorial to the Leeds Rifles outside Leeds Minster

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Further reading: Everard Wyrall (1878-1932): Military Historian

[i] British Divisional Histories of the Great War by Dr J.M. Bourne. http://www.firstworldwar.bham.ac.uk/notes/British DivisionalHistoriesoftheGreatWar.doc

[ii] Narrative of the 5th Divisional Artillery; History of 20th Division Artillery; 29th Divisional Artillery, War Record and Honours Book; Artillery & Trench Mortar Memories, 32nd Division; History of the 33rd Divisional Artillery; A Short History of the 39th (Deptford) Divisional Artillery; War Services of the 62nd Divisional Artillery.

[iii] 15th (Scottish) Division List of Officers.

[iv] The 38th (Welsh) Division in the last five weeks of the Great War, and

Breaking the Hindenburg Line: The Story of the 46th Division (the majority of the book covers the September 1918 attack.)

[v] The 51st (Highland) Division has two histories, one published as early as 1918 and the other in 1921. Similarly the 19th (Western) Division had an undated “Short” History published and another in 1932.

[vi] A further two unlisted books could arguably be included in Dr Bourne’s list, namely:

The West Riding Territorials in the Great War by Laurie Magnus (mainly covering the 49th and 62nd (West Riding) Divisions), and

The Tenth (Irish) Division in Gallipoli by Major Bryan Cooper.

[vii] The first of the 51st (Highland) Division’s histories was published in 1918 and those of the 19th (Western) Division and 50th (Northumbrian) Division were published in 1932 and 1939 respectively.

[viii] Plus two recent histories: Iron Division: The History of the Third Division published in 1978, and Ireland’s Unknown Soldiers: The 16th (Irish) Division in the Great War published in 1992.

[ix] The following analysis uses the list detailed in footnote 1, excluding the sub-unit histories in footnote 2, the “list” in footnote 3 and those covering brief periods in footnotes 4. It also excludes the duplicated histories in footnote 5 and the recently publications in footnote 8. The West Riding Territorials in the Great War is, however, included as it is only partly duplicated by Wyrall’s book on the 62nd Division. The book on the 10th (Irish) Division is also excluded as (like those listed in footnote 4) it covers only part of this division’s war service. This leaves 38 titles published between 1919 and 1939, covering the same number of divisions. (See bibliography for full listing.)

[x] Everard Wyrall published histories of the following divisions: 2nd, 19th, 50th, 62nd.

C.H. Dudley Ward published histories of the 53rd, 56th and 74th Divisions.

[xi] Middlesex Regiment; East Yorkshire Regiment; Gloucestershire Regiment; Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry; Somerset Light Infantry, Kings Regiment (Liverpool); West Yorkshire Regiment.

[xii] 17th Royal Fusiliers (33rd Division until November 1915, then 2nd Division). The battalion was a Service (“Kitchener”) battalion raised by the British Empire Committee. See Peter Simkins Kitchener’s Army, The Raising of the New Armies 1914-16. Manchester 1988

[xiii] The History of the 30th (Howitzer) Battery, RFA. This was a unit of the 1st Division. It is likely that Wyrall died before completing this. His last published work, being the History of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division, was published posthumously in 1939.

[xiv] C.T. Atkinson wrote the History of the 7th Division, as well as the Devonshire, Hampshire, Queen’s Own West Kent and South Wales Borderers Regimental Histories.

[xv] The 5th Division in the Great War was co-authored by its BGRA; The Short History of the 6th Division by its GOC; another GOC co-writing the History of the 12th (Eastern) Division. In addition two histories not included in this analysis (A Short History of the 19th (Western) Division and The 38th (Welsh) Division in the last five weeks of the Great War) were both written by men who held general officer rank within the respective divisions.

[xvi] A Brief History of the 30th Division being 64 pages long and A History of the 38th Division being only slightly longer at 86 pages. In addition, the 6th Division’s history is described in its title as “Short” as is the (undated) History of the 19th (Western) Division.

[xvii] History of the Second Division - 722 pages.

[xviii] The two volume Story of the 62nd (West Riding) Division whilst the eighth longest in terms of number of pages is arguably the most detailed as the division did not arrive in France until 1917. It could therefore be said that this history has 239 pages per whole year of active service (or 21 pages per month of active service). The closest rival is that of the Guards Division. This division, formed in August 1915 has a 708-page history, which equates to 236 pages per whole year, or 18 pages per month of active service.

[xix] The following TF divisions are not classed as ‘active service’: 43, 44, 45, 63, 64, 65, 67, 68, 69 although the 74th (Yeomanry) Division is within this classification.

[xx] K1 - 33%; K2 - 67%; K3 - 50%; K4 - 67%; K5 - 67%.

[xxi] First Line 69%, Second Line 50%.

[xxii] Significantly, in his foreword to Magnus’s book, Haig makes reference only to the 62nd Division (specifically their attack at Cambrai in 1917), presumably being unable to find anything complimentary to say about the 49th Division.

[xxiii] It is likely he started the Regimental History of the West Yorkshire Regiment at around the same time, as this was published in the same year as the first volume of the 62nd Division history. Four battalions of this Regiment initially serving with the West Riding Divisions. One wonders if the commission to write to West Yorkshire Regiment’s History came first, which would have probably assisted his ‘bid’ for the 62nd’s business.

[xxiv] Wyrall may have avoided detailing the artillery story to avoid duplication with The War Services of the 62nd Divisional Artillery written by Colonel AT Anderson and published in 1920.

[xxv] Correctly Massy-Beresford, who was killed, according to the CWGC on 23 August 1918, aged 21.

[xxvi] The Pelican was the symbol of the 62nd Division.

[xxvii] Not only does he constantly give map references – which are occasionally pin pointed on the maps within the book, but he also refers to squares (from the system used on trench maps). Without the actual trench maps themselves, the squares referred to are impossible to define on the maps provided. It is difficult to see what Wyrall thought he could usefully gain by the inclusion of this level of detail.

[xxviii] The Bloodtub. Jonathan Walker. London 1992;

The First Tank Battle. Cambrai 1917. Robert Woollcombe. London 1967.

Cambrai. The First Great Tank Battle. AJ Smithers. London 1992;

The Second Battle of the Marne. Paul Greenwood. London 1998.

[xxix] Although Jonathan Walker does pick up on this thread (then men being “hardy and spirited”) on page 53 of The Bloodtub.

[xxx] Unless otherwise stated the page numbers refer to volume 1 of Wyrall’s two-volume book.

[xxxi] It is unclear if this is a privately published manuscript, as Dr Bourne does not list this book in the battalion histories section of the web site in footnote 1.

[xxxii] Wyrall does, however, occasionally source his material. Whilst “Ludendorff” is acknowledged (but not the work) on page 20; on page 20 of volume 2 he does refer to “My War Memoirs” by Ludendorff. Later (pages 64 to 65 of volume 2) he again simply refers to “Ludendorff”.

[xxxiii] See footnote on page 73 for a description of what comes across almost as a discovery. This is a useful pointer to any amateur historian as to what can be found in the National Archives. See also page 179 for his frustration at the lack of information within the war diary (but this is more than adequately compensated for by a personal account). Amateur historians are also put on notice about not taking the war diaries at face value: page 114 of volume 2 not only describes the diary as “uninteresting” but also strongly hints that it is inaccurate.

[xxxiv] Brig-Gen. de Falbe, for instance, commanded 185 Brigade until August 1917 but is not mentioned once in the book.

[xxxv] The only time there is a hint of any criticism of formation commanders is in Chapter 14 (pages 143 to 163) when Wyrall fails to clear up the confusion about who was in charge of 187 Brigade.

Lt-Col Barton (nominally commanding 2/5th KOYLI) had taken over 187 Brigade in early February due to the hospitalisation of the brigade commander, Brig-Gen. Taylor. However during the attacks at Bucquoy, Barton had to be replaced firstly by Brig-Gen. Burnett (186 Brigade) who looked after both 186 and 187 Brigades, and later by Lt-Col James (2/7th West Yorks). The reason, given by Wyrall is that the (unnamed) Brigadier or Colonel (depending on which footnote you read) “was sick and not up to the strain” (see footnotes on pages 159 and 161).

For fuller details see Saturday Soldiers (pages 137 – 139) by Malcolm Johnson, Doncaster 2004.

[xxxvi] Wyrall, on page 63, states that the division (in July 1917) “…had yet to win that extraordinary reputation for never failing to reach its objectives which became its most precious possession before the war ended.”

[xxxvii] See the review of the 62nd Division history (probably by Col Terry Cave) at http://www.naval-military-press.com in which he quoted Cyril Falls. Falls served on the staff of the 62nd Division so his opinion may be – to a certain extent – biased.

[xxxviii] For instance, is this the reason this battalion was disbanded some three months later? Compared with the wealth of detail Wyrall supplies when the 2/5th West Yorks were disbanded in August (page 227), he makes very little reference to the 2/7th Duke’s and 2/7th West Yorks being disbanded in June 1918. This kind of inconsistency may well be a clue to a future historian but until the research is undertaken it is impossible to tell if there is indeed a story here.

[xxxix] Examples of exceptions to this are again few, but include on page 112, the 4th Grenadier Guards failing to co-operate at a relief through lack of orders resulting in 40 casualties, and again on page 120 when two squadrons of King Edward’s horse were clearly insufficient (“two brigades might have achieved the desired objective”).

[xl] The infantry battalions that served with the division during its entire period of active service receive, on average, 50 references each in the index with the exception of the 2/5th (later 5th) Duke of Wellington’s. This battalion gets 83 references in the index and also has the longest passages in the text when Wyrall describes the set-piece battles. (See the passages on Cambrai and Bucquoy in particular.) It is also noticeable that there are more than the average number of references to the battalion’s CO, Lt-Col. J Walker, including one semi-humorous story between pages 89 and 96 of volume 2. Walker was from a wealthy mill-owning family in the heavy woollen area, and it is quite possible he was a financial backer of the book. Clearly the relative wealth of information on his battalion is of use to a historian of that battalion, but this is at the expense of other units. This shows the vagaries of such a book, especially when the author may well, explicitly or implicitly, have to defer to the book’s backers.

[xli] Page 32 volume 2.

[xlii] Page 126. Within the same paragraph Wyrall correctly identifies other infantry brigades of the 31st Division, which makes this error even less forgivable.

[xliii] Pages 19 to 20 describe in some detail a raid made by the Germans, stating the battalion on the receiving end of the raid was the 2/5th West Yorks. If this was the battalion in question, the men should not have been described as “Riflemen”, this rank only being appropriate in this division to the 2/7th and 2/8th West Yorks (being the Leeds Rifles). However on closer investigation (of SDGW) it is clear Wyrall was describing a raid on the 2/8th West Yorks, so whilst he was correct to state “Rifleman” rather than “Private” when describing the troops, he has fundamentally failed to label the battalion correctly.

[xliv] Wyrall on page 57 states the officer casualties for May 1917 as being:

Killed – 24, wounded – 87 and missing –32. He gives the total of these figures as 163 (actually 143).

In Appendix VIII these figures become:

Killed – 25; wounded – 84; missing – 28. (Correctly added up to 137)

[xlv] ‘Other Rank’ casualties for May in the text are killed – 254; wounded – 1710 and missing – 1320.

The table in Appendix VIII confirms the first two figures, but then gives the missing as 1220.

[xlvi] Wyrall asserts on page 16 that 2/Lt NE Bentley was the first officer casualty (being taken prisoner of war), however Appendix VIII clearly shows 2/Lt EJ Trubshawe as being killed four days before Bentley was captured.

[xlvii] Wyrall hints at the devolution of command down to “…commanders of small units, sections, platoons and battalions” (page 73 volume 2). This is reinforced on page 98 of volume 2 when Wyrall states that “The 2/4th KOYLI had decided to attack on a two company frontage” (as opposed to being ordered to do so). On page 140 of volume 2 there is very much a sense of the thinning out of the attack, companies seemingly allotted objectives that would probably have been given to battalions or brigades earlier in the war.

[xlviii] See page 20 of volume 2 when Wyrall seems to be on the verge of explaining the series of rapid punches that were made, but fails to adequately emphasise or expand the point.

[xlix] Examples of these are moderately numerous and include:

- Lt-Col Crouch (CO of the 9th DLI) came out with his battalion as a Sergeant Major.

- The commanders of the 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions, West Yorkshire Regiment both had the surname ‘James’ and were therefore universally known as James VII and James VIII.

[l] Wyrall only occasionally mentions individual officers, and even more rarely NCO’s and men. A historian looking at operations on the Marne would note how this rule radically changes in Chapters 17 and 18. It is likely the unexpected naming of a number of NCOs and men would be a profitable area of study, for example, in respect of medals awarded to the named soldiers.

[li] Compare the account of Bullecourt on 3 May 1917 with that of the opening of the attack at Marfaux on 20 July 1918. The former is covered in a little over five pages, whilst the latter has 15 pages devoted to this day’s attack.

[lii] Perhaps the best example of this is on page 187/188 when Wyrall uses an unsourced private diary (probably Captain Reay) to gloss the attack at Marfaux.

[liii] It is striking how Wyrall’s style and approach to the book changes at around page 169 (i.e. the start of the chapters about the division’s operations on the Marne) when he makes more use of private diaries and anecdotes than in the rest of the book put together. These passages contain lyrical passages about the conditions in which the division was fighting (page 183) which may have inspired Wyrall to try his own hand at ‘purple prose’ (the “golden panorama” of page 181). All of this should be irrelevant to the historian, but nevertheless it does draw the eye and possibly inspire readers / historians to find out more of this period.

[liv] Chapter 7 (pages 59 to 68) is entitled “Trench Warfare” and Wyrall does in this chapter cover this aspect of the division’s active service in a reasonably interesting and informative manner.