FILM REVIEW : All Quiet on the Western Front

- Home

- World War I Articles

- FILM REVIEW : All Quiet on the Western Front

This article by Prof. Stephen Badsey first appeared in the December issue of Bulletin 123.

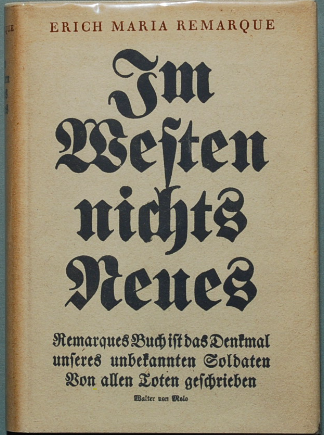

This is the first ever German film to be based on Erich Maria Remarque’s bestselling novel of 1928 Im Westen nichts Neues, better known as All Quiet on the Western Front through its Hollywood adaptation in 1930, directed by Lewis Milestone.

(There was also a version made for television in 1979, with Richard Thomas and Ernest Borgnine horribly miscast in the lead roles.)

This new All Quiet on the Western Front, which is best watched in the original German with English subtitles, was released this October simultaneously in cinemas and on Netflix. It needs to be said at once that the film is an artistic masterpiece, with beautiful direction, cinematography and editing, a pastoral colour palette and evocative background music, viscerally violent battle scenes, and some excellent acting. But it is not a faithful adaptation of Remarque’s novel, and it is a hopelessly inaccurate depiction of the Western Front. Western Front Association members who criticised Warhorse (USA: 2011) and even 1917 (UK: 2019) for historical errors should suspend their disbelief.

The extent of the filmmakers’ disregard for history is best shown by their film’s concluding captions, 'At the end of the war in November 1918 the front-line had barely moved. More than three million soldiers died here, often while fighting to gain only a few hundred metres of ground'. As all WFA members know, in August-November 1918 the Allies broke through the German lines and had driven them back 50-70 miles on a front of 150 miles by the Armistice. Among the more disturbing products of the war’s centenary has been a revival of two long discredited interwar German and American beliefs: that the First World War was purposeless and was continued only by incompetent generals and politicians, and with it the 'stab-in-the-back myth' that the German Army was undefeated on the Western Front; All Quiet on the Western Front incorporates both these discredited ideas

Any historical film tells you first about the year in which it was made, and only perhaps then about the year in which it is set, for entirely commercial reasons. A modern bestselling novel might sell 100,000 copies, but with a $350 million production budget, All Quiet on the Western Front needs to appeal to a mass audience of millions, and above all to young people in Germany and the United States who are unfamiliar with the First World War. In their re-imagining of Remarque’s anti-war novel, (or in commercial terms their exploitation of an internationally famous brand to sell their new product), the filmmakers have intentionally drawn on the deeply ingrained German pacifist tradition established after two disastrous world wars, and on a set of shared literary and filmic tropes, depictions meant to make the viewer ask how anyone could have been so stupid or callous as to behave in such away.

All Quiet on the Western Front goes significantly further in its anti-war and anti-authority stance than even Remarque’s novel, which from its publication onwards has been hailed as a pacifist masterpiece. Remarque’s own front-line experience was very short, just over a month in the Ypres Salient before being injured by mortar fragments on 31 July 1917, at the very start of the Third Battle of Ypres. Translated into English and many other languages a year after publication, the novel was factually based on the stories of other German veterans, selected to depict only the miseries of military life and the horrors of the trenches, rather than the complex war history that actually existed. The novel’s story, closely followed in the 1930 version of the film, is narrated by Paul Bäumer, a young German inspired by patriotism to volunteer together with his school friends. After some brutal basic training, the boys join their regiment (the fictitious 78th Reserve Infantry Regiment) on the Western Front in 1915, fighting against the British and French, where they are befriended by the trench-wise Stanislaus ‘Kat’ Katczinsky. In a series of vignettes, Paul and his friends become increasingly disillusioned and alienated from their families at home, preoccupied only with survival and finding food. In the last few weeks of the war they are all killed, including Kat, until only Paul survives. Then the novel delivers its gut-punch with a short coda: “He fell in October 1918, on a day that was so quiet and still on the whole front, that the army report confined itself to the single sentence: All quiet on the Western Front ''.

This new version of All Quiet on the Western Front departs considerably from Remarque’s novel. It starts in Spring 1917, with the underage Paul (excellently played by Felix Kammerer, an Austrian stage actor in his first film) and his classmates volunteering, but omits any training scenes before they join their regiment at a fictional location in the Aisne region, where one of them is killed in a French bombardment. All this takes just 35 minutes of screen time, after which the film jumps forward 18 months to 7 November 1918. There is no space for character development, they have been made brutalised and disillusioned by their very first encounter with the war. Somehow, the mud and rain of the Aisne district acquires Christmas-card frosts, snows, and distant mountain peaks. Paul’s remaining friends all die offscreen, except for one who cuts his own throat in a field hospital (in Remarque’s novel he wanted to live), rather than survive as a cripple, and Kat (also excellently played by Albrecht Schuch) who is fatally wounded, shot by a child while stealing food from a farmhouse.

Principal filming for All Quiet on the Western Front took place between March and May 2021 in Germany, Belgium and in the Czech Republic, where a battlefield the size of three football pitches was constructed for hundreds of extras, stuntmen and authentic-looking dummies; the film also uses CGI well. In terms of authenticity, the trenches are a reasonable representation for the mid-period of the war, although obviously wrong for its last few weeks. They are deeper and wider than most real trenches, to allow space for the film equipment, usually with no duckboards so there is plenty of mud for the actors to wallow in, and with a very inauthentic barbed wire layout. Tactics in particular are those of Hollywood convention. Medium machine-guns spray continuous fire from side to side rather than short bursts on fixed lines; there are no mortars or light machine- guns; shell bursts are random, there is no creeping barrage; the Germans charge together across no man’s land in mob waves, tossing hand grenades and abandoning their rifles, and the French are ordered to charge out of their trenches to meet them; there are no reserves, and the successful Germans at once start looting the trenches. In short, everything that by the later part of the war made it possible for soldiers to survive and win, and which eventually led to the Allied breakthrough, has been omitted. Much of the combat is hand- to-hand, and Paul fights like a brutalised and vicious automaton, never thinking of running or surrendering (this is brilliantly depicted in Felix Kammerer’s acting), although he is often briefly remorseful afterwards. In one of the film’s most visually impressive scenes, a French assault with Saint-Chamond tanks without infantry or artillery support (they should really have been Renault FT17s) drives the Germans out of the trenches that they have just captured.

The reason for the film’s jump to end of the war is that the screenwriters have interpolated into the fighting on the Western Front scenes of the final Armistice negotiations in the railway carriage in Compiègne forest, which also has serious historical inaccuracies. (Disclosure: I gave a webinar talk for the WFA on exactly this topic in November 2021; see 'The Armistice and How the War Ended'. The chief German negotiator Matthias Erzberger (played by Daniel Brühl, one of the film’s executive producers, who has suggested that it should be shown in school history classes), is portrayed as concerned only to stop the pointless slaughter on humanitarian grounds, in contrast to an almost cartoonish Marshal Ferdinand Foch (Thibault de Montalembert), determined to extract the maximum revenge and humiliation from his enemies. This idea of a vindictive French peace imposed on innocent Germans, leading inevitably to all that was bad that followed, was another common German and American interwar belief, now also discredited. While slightly earlier films about the First World War with German input, such as Joyeux Noel (2005) and the ridiculous The Red Baron (2008) took the same line as Remarque, that all men are brothers and war is a collective tragedy, this All Quiet on the Western Front is distinctly anti-French, in keeping with recent changes to American and German attitudes. The young French boy who shoots Kat has pure hatred in his eyes, while in another inaccurate battle scene, a line of massed French flamethrower operators incinerates the helpless Germans at point-blank range, rather than taking them prisoner. The film ends as the last hour counts down to the Armistice, and a German general (another disappointingly cartoonish figure in a film that is generally well written and acted) orders his men to retake the lost trenches in a final attack, to keep their honour after the war. Paul is killed by being bayoneted in the back in the last seconds before the Armistice, thus making nonsense of the film’s title and Remarque’s intentions.

None of this makes All Quiet on the Western Front a bad film. There is nothing inherently wrong with a well-made war film not following history exactly, if it reveals something about the human condition and the nature of war. Examples include Zulu (UK: 1964) and A Bridge Too Far (USA: 1977), both of which included serious historical errors, but both of which also generated public interest that made further serious research into the real battles sustainable. Any major film that is released with publicised claims of great historical authenticity goes through an unvarying process. First, it is praised for its accuracy by historically illiterate film critics; then its obvious flaws are challenged by historians; then either the historians are ignored, or after some squabbling its makers fall back on dramatic licence and it being just a story. A recent very prominent case is the highly controversial The Woman King (USA: 2022). This process is only just beginning for All Quiet on the Western Front, and whether it will generate the same levels of debate remains to be seen. But to repeat, this film is a visual and acting masterpiece, and a product of its own time and country; it should be watched, understood and appreciated in that way.

Stephen Badsey