First World War Graves and the Memorial to the Missing in Persia

Whilst investigating the stories of three Indian Army officers who were ‘killed by treachery’ in April 1915 it became necessary to look into the history of the Tehran Memorial to the Missing which details those with no known grave from the First World War who fell in Persia (now Iran).

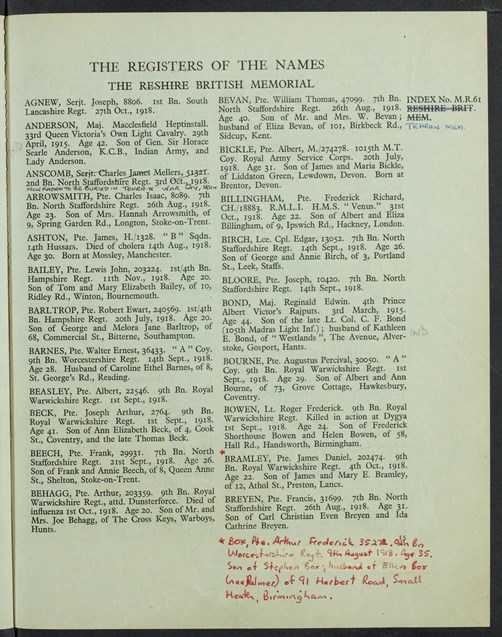

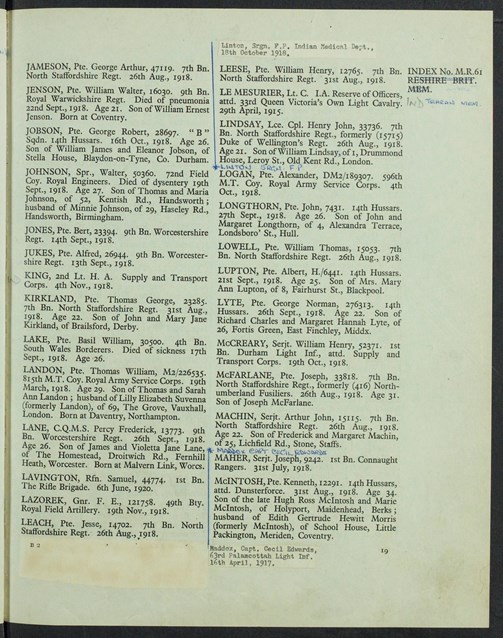

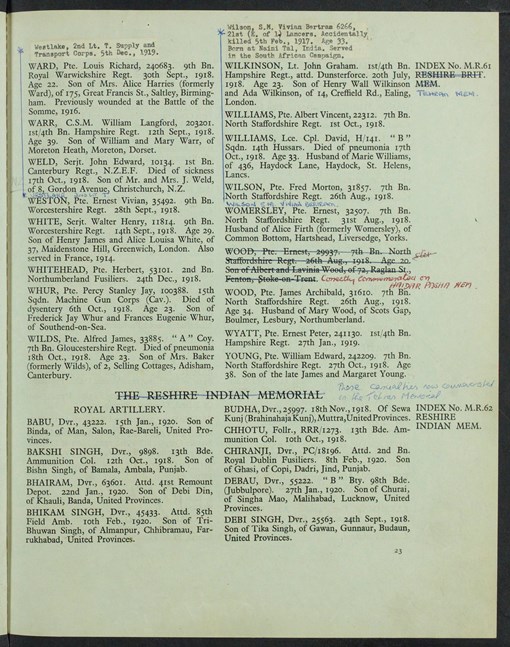

The CWGC’s registers of the names listed on the Tehran Memorial indicate the memorials that originally carried the names of the missing from this period were in fact the Reshire British Memorial and the Reshire Indian Memorial. Both of these memorials are now ‘merged’ and the names appear on the Tehran Memorial which was built in the early 1960s.

The total names listed at Tehran are just short of 3,600 men which includes those who fell in what is now Iran and also in neighbouring regions of Russia. Of the 3,600 named, the vast majority (3,370) are largely ‘other ranks’ of the Indian Army (14 British men who were Indian Army officers are included in this number). The remainder (just over 200) are the missing of the British Army; virtually all of the these being deaths due to the operations of ‘Dunsterforce’ at the end of the war. A small proportion of the Indian Army fatalities (approximately 230) are for the period 1914-1917.

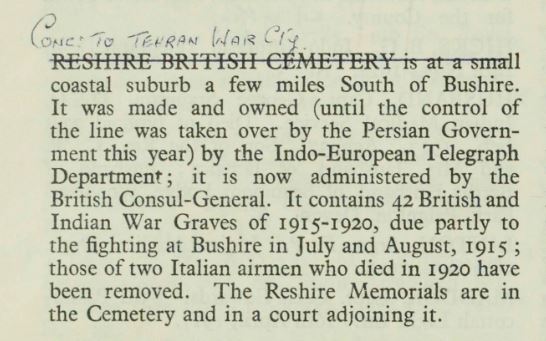

Further investigation revealed that not only were there two Reshire Memorials, there was also a ‘Reshire Cemetery’. This, too, had been moved to Tehran in the early 1960s.

Delving further into this, it was found that Reshire (or Rayshahr) is situated just 5 miles south of the city of Bushire (Bushehr). On google maps Reshire/Rayshahr is rendered as ‘Rishehr’ and is situated on a small peninsula on the Persian Gulf.

Reshire Cemetery

The history of the cemetery (which is located on the western side of the Bushire peninsula) and the memorials is highly complicated with decisions and counter-decisions being made over a period of nearly 50 years. The cemetery was abandoned as a war cemetery in 1963 after the removal to Tehran of the remains of those killed in World Wars I and II. A visitor in 1966 found some thirty to forty graves, many unidentifiable, dating from 1815. Another visitor in 1976 noted the remains of a mutilated large marble plaque listing names and regiments of soldiers killed in the First World War.[1] The article below summarises what can be gleaned from the files available online at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission supplemented by other sources.

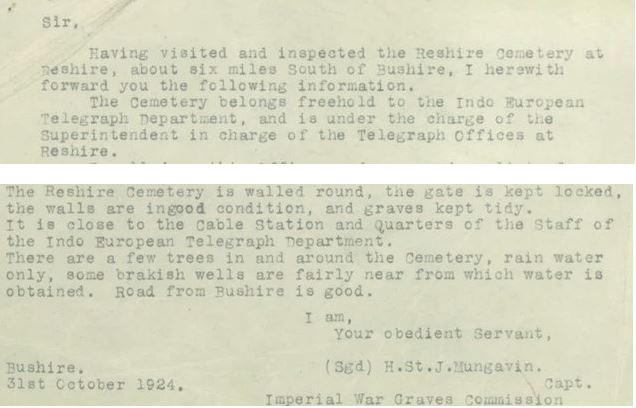

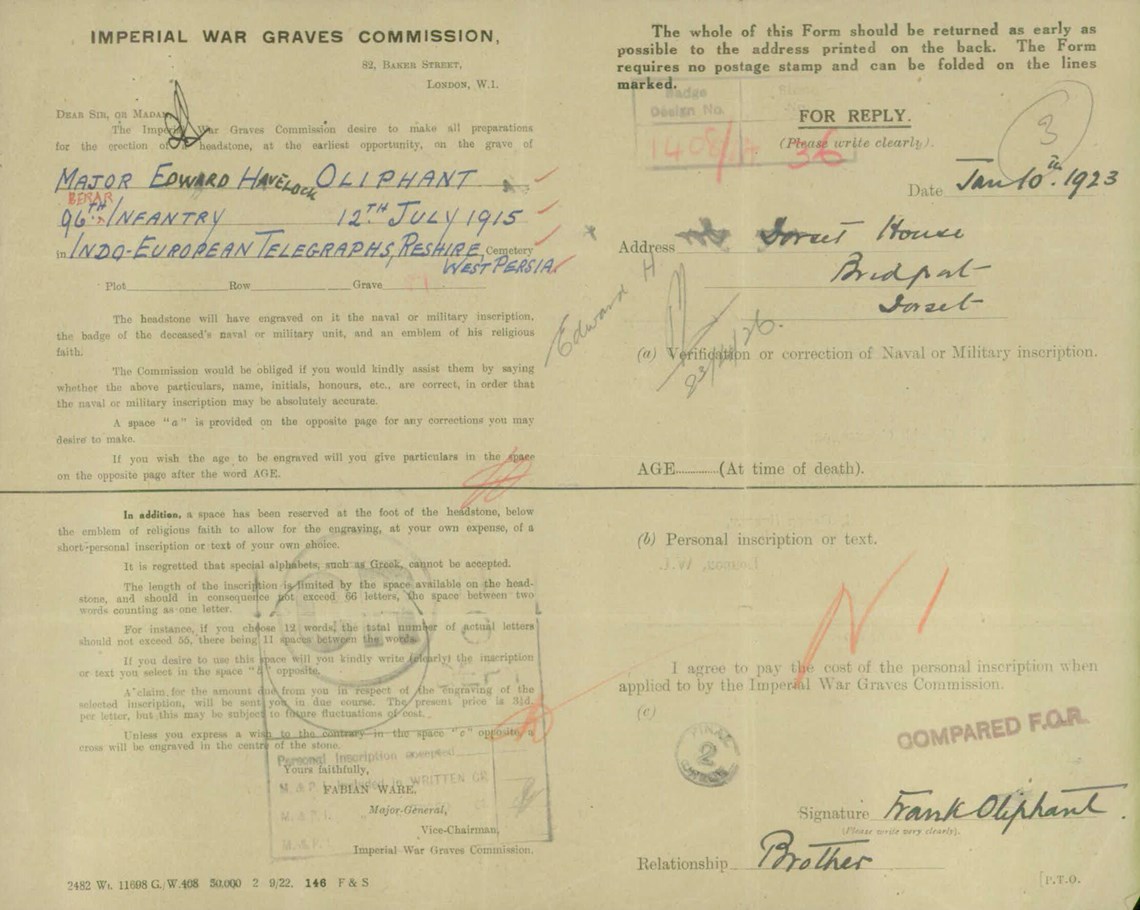

Bushire was the East India Company's Persian Gulf headquarters from 1778-1857 and, until 1946, the seat of the British Resident for the Persian Gulf, a proconsular figure appointed by the Government of British India.[2] The Reshire British Cemetery was originally called the Reshire Indo-European Telegraph Department Cemetery.[3]

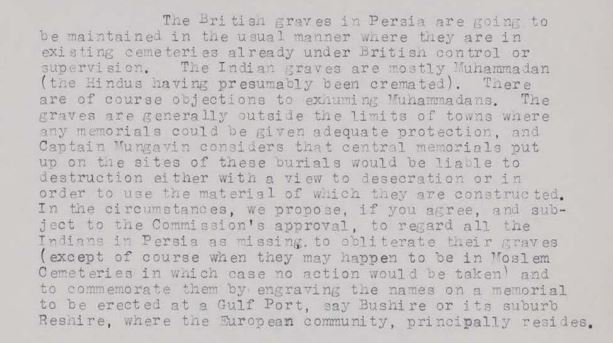

A letter from the IWGC to ‘Colonel Chitty’ of the India Office dated 26 September 1925 set out the problems that were perceived in commemorating the Indian dead in Iran.

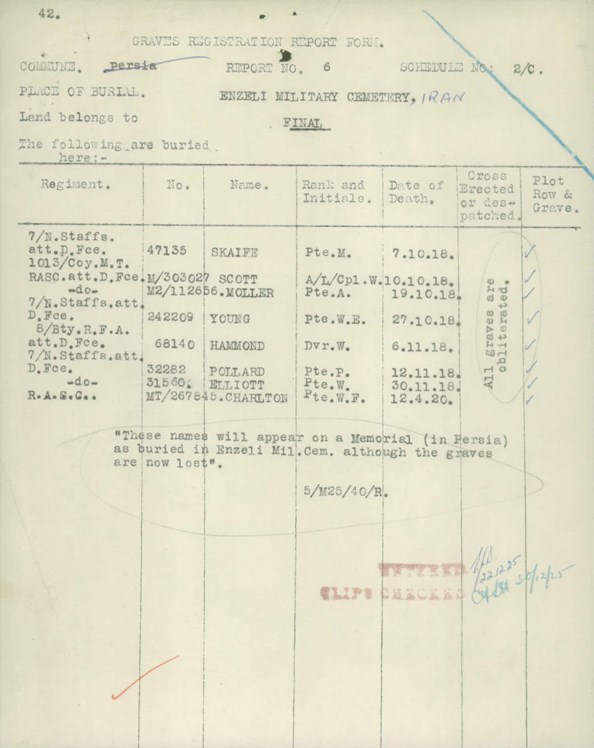

Some discussion ensued about the definition of ‘missing’ when the original graves were known (but obliterated): were these men ‘missing’ or should they be commemorated with a ‘Kipling Stone’?

It must be assumed that Reshire was chosen at an early date as the preferred location of the memorial to the missing in Persia due to nearby Bushire being the headquarters of the British Resident for the Persian Gulf. It had the added advantage of being accessible by ship, being a port city.

Letters went back and forth detailing the plans for the Reshire Cemetery and Memorials showing there was clear early determination to ensure full commemoration of the British and Indian missing. An early estimate of the number of ‘European’ names needed to be listed was 100 (it turned out to be more than twice this number) but the number of Indian names was – at least initially – uncertain, but known to be “considerably greater” and there was “almost unlimited room for all the names [to be listed on the memorial in the Reshire Cemetery grounds].”

In 1925 it was formally decided that a central memorial to commemorate all the missing in Persia “both British and Native” would be erected in Reshire and that the memorial should be in the Cemetery at Reshire. Despite this, there were clearly some misgivings, with Captain Mungavin in 1926 advocating the British Memorial being placed in the legation grounds in Tehran, but this was objected to by the Foreign Office.

Subsequently, however, it was agreed that the Indian Memorial would be erected not in the cemetery at Reshire but “in the British Consulate Offices Compound in Bushire and [it would] take the form of tablets to be affixed to the wall of the compound”. The rationale for this change of mind being that the act of commemorating Hindu and Muslim soldiers on the walls of a Christian cemetery did not seem appropriate and could offend religious sensibilities. It was pointed out that the Indian graves in the cemetery at Reshire were in fact Christian Indian troops, of the 71st Punjabis (“a Christian Battalion specially raised in the war”).[4]

The Consulate grounds – it was agreed – would be the ideal place for the Indian memorial as it was fully accessible “and visited by people of all classes”.

Discussions took place about some of the detail of the commemorations, including, for example whether the South Persian Rifles should be included (it was deemed that they owed their allegiance to the Shah of Persia and should not be commemorated, apart from those British officers who were seconded to the unit). It was also debated as to whether the original place of burial (for those cemeteries or individual graves were lost or ‘obliterated’) should be listed on the memorials or in the published register. It was decided that the names would be listed by regiment (as was the usual practice) and not to list them based on the original place of burial.

Other discussions took place about the use of the word ‘graves’ rather than ‘burials’ as Hindus were cremated.

Eventually an order was placed for the stone ‘Name panels’ at Reshire – this was to be ‘Blue Bangor Slate’ and detailed specifications about the quality, dimensions and shipping were issued. Humphrey Williams and Co. of Bangor were successful with their tender and a detailed contract was signed on 21 October 1929 and the Penlon Slate Works at Bangor was the quarry where the stone was to be sourced from.

As late as 1930 names were being put forward to potentially be added to the list of the missing for the memorial that was to be constructed at Reshire.

Another problem arose when it was realised that those men of ‘Dunsterforce’ who fell in and around the Caspian Sea and at Baku could not be accurately said to have fallen ‘In Persia’ which was the phrase that was being used on the memorials. However by this time the memorial had apparently already been cut.

In 1930 the decision to place the Indian memorial in the Consulate grounds was challenged in a letter written by the ‘Political Agent in the Persian Gulf’ on the basis that the walls may not be large enough to accommodate all the panels, the building was simply an office and therefore had no associations of any kind (presumably with the military or ‘remembrance’) and finally because there was the chance the building would be ‘given up’ in the future. It was suggested the Reshire Cemetery would be the better place for the location of the Indian Memorial – even though this had been the original idea, but had been rejected on religious grounds.

This letter caused a re-think and it was suggested the names of the Indian Army dead could be added to the Delhi Memorial but after consulting with Sir Edwin Lutyens the ‘Delhi’ proposal was vetoed. An alternative was needed. After discussion about adding the names to the walls of Reshire Cemetery came up again – and again was dismissed as it would be unacceptable for Hindus and Muslims – the suggestion was that the names should be added to the outside wall of the cemetery, although this created its own set of problems as it was thought the panels would be damaged by locals.

It was eventually decided (in 1931) to wall-off part of the Reshire Cemetery that did not include burials and that this wall would be able to hold the panels for the Indian ‘missing’. By the end of the year a ‘Final List’ of names was compiled which would enable the panels to be inscribed.

There is no further correspondence in the file, but in July 1937 a report was written by someone within the Imperial War Graves Commission (we know his initials only – being ’HFC’) and he set out the position regarding the Reshire Memorial. He records how he had been asked – towards the end of May - by ‘The Junta’ to put on record the facts about the Reshire Indian Memorial in Persia.

HFC’s report explained that although the cemetery at Reshire had been the property of the Indo European Telegraph Department, in 1931 – when the department was wound up - the Consul General discovered that no title deeds existed for the older part of the cemetery.

In 1931 the memorial registers were published [these are now available on the CWGC website] but a year later the Commission changed its mind yet again about the location of the memorial due to the lack of title deeds. Presumably the problem ‘hung around’ and had not been resolved when ‘HFC’ wrote his report in 1937, which concluded with the suggestion that “no great harm could be done by waiting a little longer in the expectation that the tenure of the cemetery can be regularized”.

It would seem that nothing further was decided, and the Second World War then came along so matters were left in abeyance until 1963 when the Tehran Memorial was constructed. No new registers were published, which is why the names on the original register suggest the memorial is in Reshire.

Reshire Cemetery today

As detailed above, the tablets for the Reshire Memorials were ordered and HFC’s report implies that the order was cancelled (he states “the matter was withdrawn from the Finance Committee because of the uncertainty of the tenure of the site"). The Director of Works was requested to re-submit the matter when the Legal Branch could obtain ‘solid assurance of the security of the site’….Letters have been addressed from time to time [presumably this was between 1932 and 1937] asking whether the way is now clear to register the property, but on each occasion the Ministry has replied that a Registration Office has not yet been opened at Bushire, but that there are local rumours that it will be opened shortly”.

It is far from clear that the panels were ever created let alone installed in the cemetery. As can be seen below, this cemetery (it is locally known as the ‘English Graveyard’) still exists, although the First World War Graves have been removed and are now within the British Embassy grounds in Tehran.

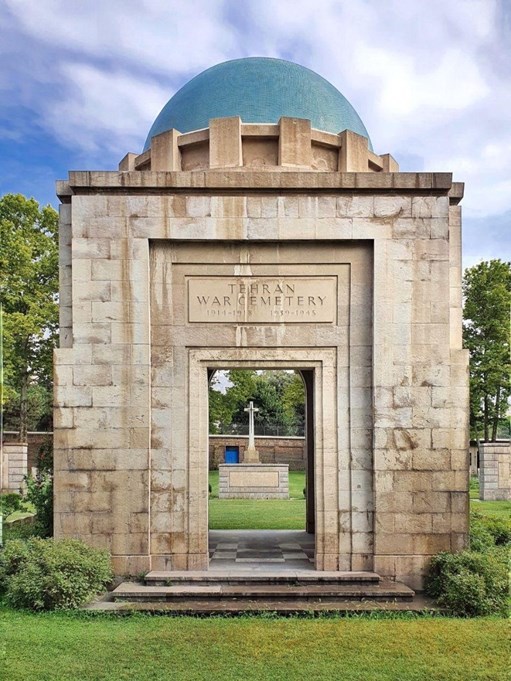

Tehran War Cemetery

Examining the cemetery register for the Tehran War Cemetery, it can be seen that this has a total of 571 identified burials, of these 149 date from the Second World War.

Of the 422 other identified burials, 21 British graves were concentrated in from Reshire Indo-European Telegraph Department Cemetery.

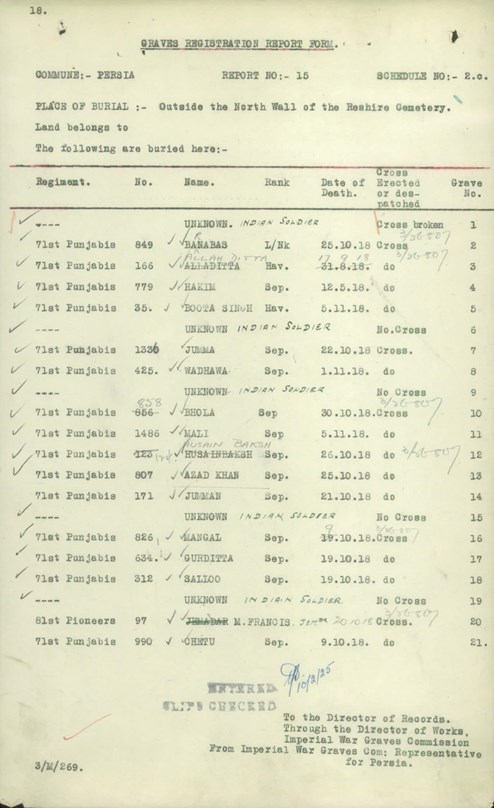

In addition a further 16 Indian graves were noted as coming from outside the boundary of the cemetery (these are the identified of the 71st Punjabis plus the five ‘unknown’ graves mentioned above).

This leaves a large number of graves that were concentrated in to Tehran from other parts of Persia (and adjoining regions of Russia). The cemeteries from which these burials came can be summarized as follows:

Hamadan Military Cemetery – 167 graves. This cemetery was located about 200 miles south-west of Tehran.

Kazvin British War Cemetery (previously known as Kazvin Russian Cemetery) – 148 graves - Kazvin or Qazvin as it is now known, was a former ancient capital of the Persian Empire, and lies approx.150 km north-west of Tehran.

Shiraz British Cemetery – 22 graves – Shiraz is approximately 170 miles east of Reshire

Resht Armenian Cemetery – 7 graves – this may be 'Rasht' on the Caspian sea

Chashmeh-i-Zuliak Anglo-Persian Oilfields Cemetery - later known as Mashid - I Sulaiman Cemetery – 5 graves

Akhbarabad, Tehran – 3

There were also graves at Naibund British Cemetery, but - as explained below - the burials here became part of the ‘Addenda panel’ on the Tehran Memorial.

Buried in the Tehran War Cemetery is one Frenchman, F.E.M. Couet (who died on 1 August 1918) (II.G.5) who was originally buried at Kazvin and eight civilians who were either the wives or children of serving soldiers (one was the son of the Consul).

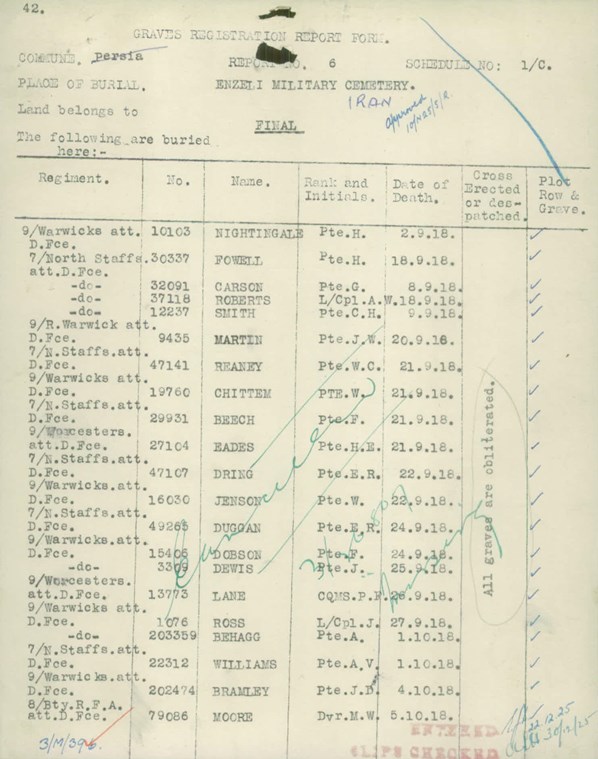

Also buried in Tehran War Cemetery and dating from the First World War are ten Russians, (some of whom are unknown) including one Nursing sister - Marie Toran (V.A.4), one high ranking officer - Colonel CT Kisselev (III.F.1) plus 2/Lt A Ivanoff (IV.G.16), Capt Prassoloff (V.C.7) and 2/Lt N Sudovikov (II.G.1) who was known to be attached to Dunsterforce. The Russians were originally buried at Kazvin and Hamadan.

Special Memorials (Kipling Stones)

Within the files of the CWGC there are discussions about ‘Kipling Stones’ (which was the IWGC’s internal name for ‘Special Memorials’ for men whose graves had been lost). There are now ten First World War Special Memorials within Tehran War Cemetery.[5] Five of these are for men who were originally buried at Senna Chaldean Cemetery but whose graves were lost. As their graves were lost, they were commemorated by means of ‘Special Memorials’ at Hamadan Military Cemetery. These memorials are for: GH Slaughter, JS Steeples, G Thornton, E Hall, HL Le Grys. Two others, Second Lieutenant PA Bourdillon and Captain HC Pallant were originally buried at Kain Military Cemetery. Their graves, too, were lost and they were also commemorated with special memorials at Hamadan Military Cemetery.

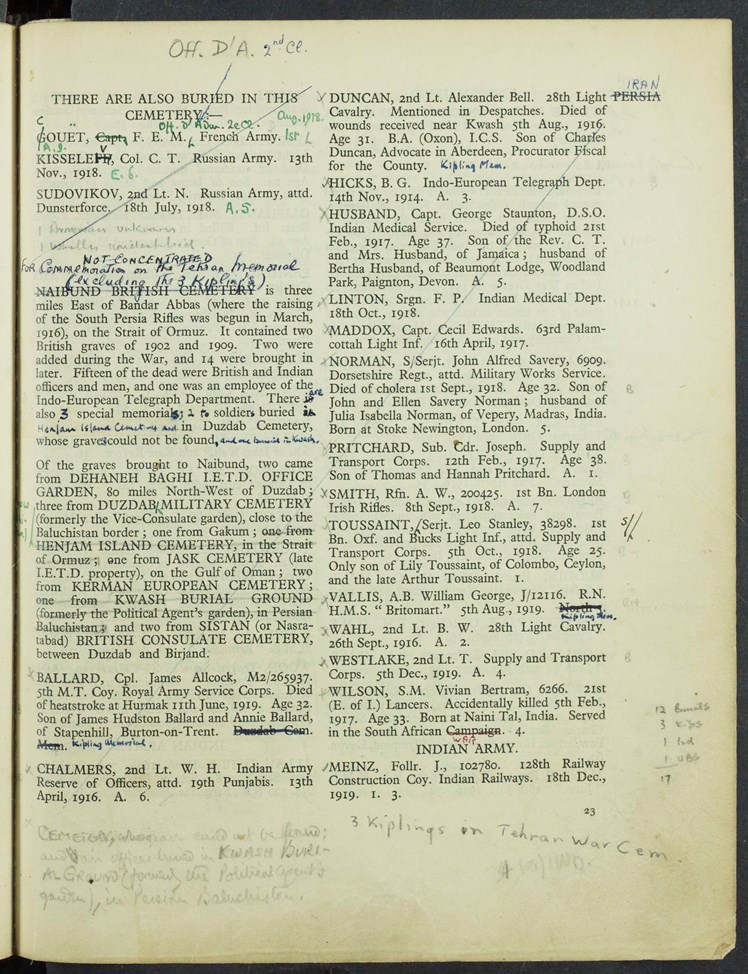

The final three special memorials are to WG Vallis who was buried in Henjam Island Cemetery, JA Ballard who was buried at Duzdab Cemetery and AB Duncan who was buried at Kwash Burial Ground.

Tehran Memorial

The memorial lists those who died in the First World War up to August 1921.[6] It comprises six free standing walls which contain panels on both sides of each structure. These panels are ordered by the army in which the men served – firstly British then Indian.

British Army

The five panels containing names of those from the British Army are rendered in order of precedence, with the Royal Navy (there is one RMLI fatality) followed by Cavalry and then Infantry Regiments.

It is of note that two New Zealanders appear on panels 5 and 6. There is also an addenda panel which will be looked at in some detail later.

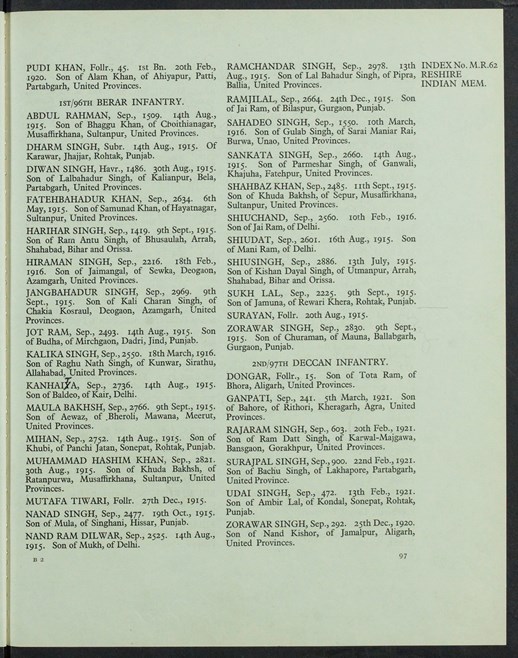

Indian Army

The panels numbered 6 to 59 detail those of the Indian Army who have no known grave. Starting with the Indian Army Reserve of Officers (Lieutenants Dixon and Le Mesurier) it goes on to detail Royal Horse and Field Artillery, Royal Engineers, then three men from the Machine Gun Corps before listing Indian Army Cavalry Regiments. These are (in order):

26th King George's Own Light Cavalry,

27th Indian Light Cavalry,

28th Indian Light Cavalry,

33rd (Queen Victoria’s Own) Light Cavalry,

34th Prince Albert Victor's Own Poona Horse,

36th Jacob's Horse,

21st Prince Albert Victor's Own Cavalry (F.F.) (Daly's Horse),

22nd Sam Browne's Cavalry (Frontier Force),

11th King Edward's Own Lancers (Probyn's Horse),

12th Indian Cavalry

17th Indian Cavalry

37th Lancers (Baluch Horse)

40th Indian Cavalry Regiment

41st Indian Cavalry Regiment

42nd Indian Cavalry Regiment

Gwalior Lancers

The order of precedence for Indian Army cavalry regiments during World War I was a complex system influenced by various factors including the regiment's formation date, its status as a "Royal" regiment, and its history.[7]

After the cavalry, there appears – on panel 11 – the Indian Mountain Artillery and other artillery formations, followed by ‘Sappers and Miners’.

From panel 15 we see infantry with many different and exotic sounding regiments listed.

Some regiments have hundreds of names listed, the most numerous being the 16th Rajputs (Lucknow Regiment) which has 283 named soldiers listed. Others with a heavy casualty list are the 98th Indian Infantry which has 256 named soldiers and the 124th Duchess of Connaught's Own Baluchistan Infantry which has 233 named soldiers.

Eventually, on column 59 we have 32 men from the Indian Railways.

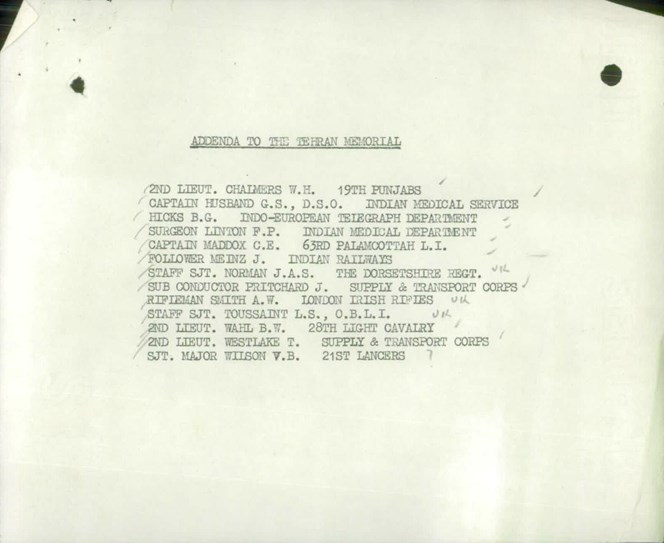

Addenda panels

There are a number of names of the Addenda panels which are of interest

The thirteen men named here were either originally buried or re-interred in Naibund Cemetery after being originally buried in different locations.

Naibund British Cemetery was three miles east of Bundar Abbas (now Bandar Abbas) where the raising of the South Persia Rifles apparently commenced in March 1916. This city sits on the Strait of Hormuz. It contained two British graves of 1902 and 1909.[8] As they were non-war deaths they are not commemorated on the Tehran Memorial. Two men were buried in Naibund cemetery during the war, being Sgt LS Toussaint, and Sergeant-Major VB Wilson. In addition Staff Sergeant JA Norman was brought in to the cemetery from his original burial at Gakum. (This is probably now Gahkom).

Further re-interments came in to Naibund after the war from the following locations:

Duzdab Cemetery (formerly the Vice-Consulate Garden) close to the Baluchistan[9] border contained the graves of 2/Lt Westlake and Follower J Meinz (of the Indian Railways) plus an unknown British soldier. In addition, as mentioned above, James Ballard was buried in Duzdab, but for some reason now has a ‘Special Memorial’ in Tehran Cemetery rather than being named on the Tehran Memorial. Duzdab (now known as Zahedan) is very close to the Iranian/Pakistan border.

Dehaneh Baghi (the garden of the Indo-European Telegraph Department Office) (80 miles north-west of Duzdab) held the graves of 2/Lt WH Chalmers and 2/Lt Wahl.

Sistan (or Nasratabad) British Consulate Cemetery (between Duzdab and Birjand) was the burial place of BG Hicks and Joseph Pritchard (both civilians)

Kerman Cemetery was the site of the graves of Private AW Smith and Captain GS Husband

Henjam Island Cemetery held the grave of William George Vallis a crew member of HMS Britomart (a Bramble Class gunboat) whose grave is now a ‘special memorial’ within Tehran War Cemetery, as well as Surgeon SP Linton (Indian Medical Department).

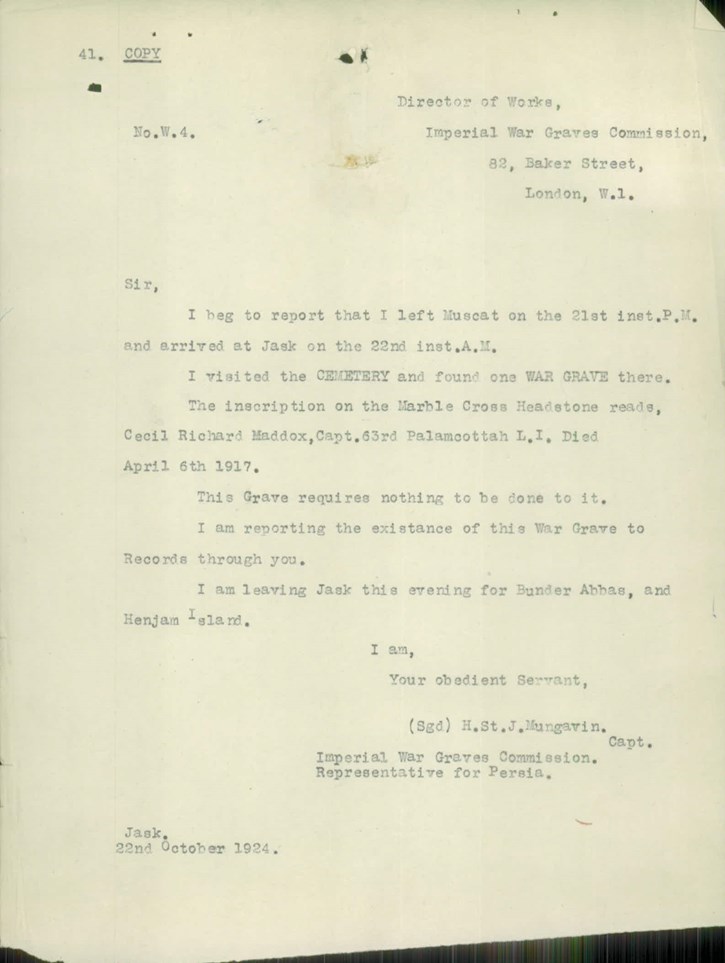

Jask Cemetery (late Indo European Telegraph Depatment property) on the Gulf of Oman contained the grave of Captain CE Maddox

Kwash Burial Ground (formerly the Political Agent’s garden) in Persian Baluchistan was the location of the grave of 2/Lt Alexander Duncan (28th Light Cavalry) but the cemetery could not be found so he has a ‘Kipling Memorial was erected in Tehran Cemetery. (Kwash is now Khash near the Pakistan border.)

In addition to the 13 originally named, two more names have been added recently to the addenda panels on the Tehran Memorial, being George Jones and Arthur Box.

All of the above-named cemeteries were, as stated above, concentrated into Naibund British Cemetery but these are only a small proportion of the total cemeteries in Persia. In a report from Captain Mungavin dated 7 October 1925 he set out those British cemeteries he had located together with recommendations about how they should be dealt with. There were four groups.

Cemeteries to be maintained in situ and headstones erected with the number of graves shown in brackets.

Kazvin Russian (138)

Kerman (2)

Resht Armenian (7)

Shiraz (22) (‘already done’)

Sistan (2)

Tabriz (1)

Dehaneh Baghi (2)

Henjam Island (1) – curiously there were two graves here, which are detailed above

Reshire (21) – this excludes the Indian graves obviously – see below

Hamadan (115)

Jask (1)

Meshed (2)

Akbirabad (3)

Duzdab (1)

Maidan-i-Napthn (3)

What is immediately remarkable is the recommendation to keep individual graves and tiny groups of burials in place and not to recommend they be concentrated.

As we know from above, Hamadan Military Cemetery – with 167 graves – was concentrated ultimately into Tehran which shows that it became partly a ‘concentration cemetery’ immediately after the war. Similarly Kazvin British War Cemetery grew to 148.

Shiraz did not expand and remained at the 22 burials as did Resht Armenian with seven and Akhbarabad (he called it Akbirabad) with three.

The second group of cemeteries Mungavin recommended to be concentrated.

Gakum (1) To Bundar Abbas

Kwash (1) To Sistan

Robat (4) To Sistan

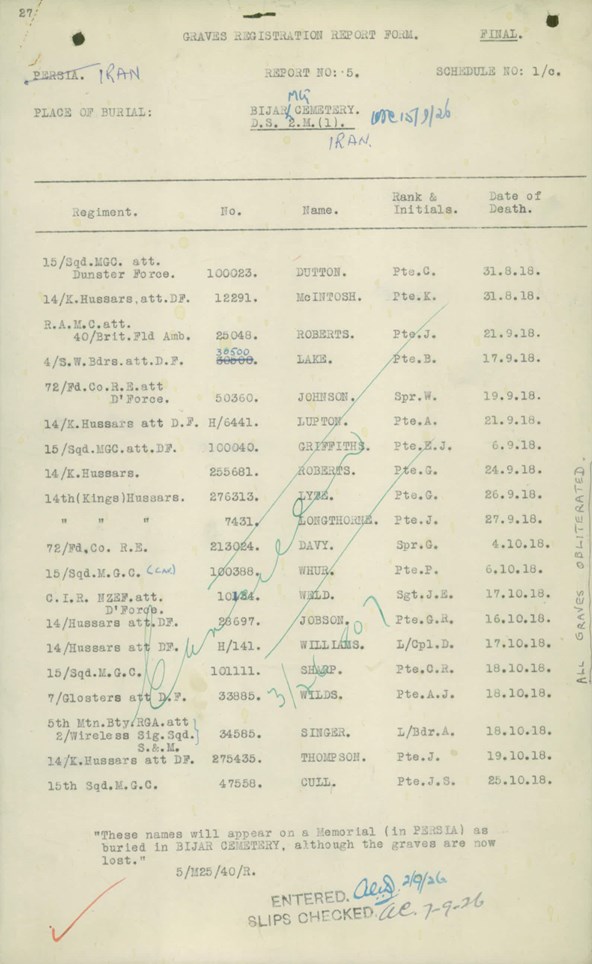

Bijar (21) To Hamadan

Karind Cemetery (8) To Hamadan

Karind Camp (11) To Hamadan

Khukhurd Bala (2) To Hamadan

Senna (5) To Hamadan

Kermanshah (41) To Hamadan

Shushtar (1) To Maidan-i-Napthun

Dar-i-Kazina (1) To Maidan-i-Napthun

Quaraitu (1) To Baghdad

Zinjam (14) To Kazvin

Again it is possibly to draw a little more out of this list. The concentrations into Sistan did not take place and Sistan remained the site of just two graves. Also, not all of the concentrations to Hamadan can have taken place as it grew from the 115 in this report to only 167 which is less than the total number of recommended concentrations.

The Bijar graves were dealt with via a memorial as can be seen on the Grave registration form below. It is likely this memorial was placed in Hamadan Cemetery and may have been ‘Kipling Stones’ (headstones commemorating their original burial with ‘Their Glory Shall Not be Blotted out’ as an inscription). These Bijar burials are now commemorated on the Tehran Memorial

Captain Mungavin then listed a third long list of eighteen places he'd visited where no graves could be found or had already been obliterated.

A final small group of cemeteries were those that Captain Mungavin had not yet visited – being Ahwaz, Kain and Khunik with four, two and one graves respectively.

The report from Captain Mungavin ends with a summary of the Indian Cemeteries. He writes “The sites of Indian graves have been located in many places but the graves themselves are not individually identifiable except at Reshire and Hamadan.” He then goes on to list examples of places at which cemetery and grave sites have been found. These include some sites which were listed earlier in his report as containing British Graves (for example Kazvin). The largest of those he listed were Bunder Abbas (60 burials) and Ahwaz (54 burials).

He goes on “In these and other cases the graves cannot be individually identified, so the erection of individual headstones is not possible. Central memorials could be erected (he probably means within each site he had found) … but [these] would not be respected unless specially guarded, the expense of which would be prohibitive. It is suggested that the only feasible way of commemorating them is to regard them as missing and to commemorate them on a central memorial relating to the whole of Persia.” He then goes on to suggest Reshire as the location of the memorial to commemorate the missing “both British and Native” individually by name.

An attempt to summarise the list of cemeteries and grave sites in Persia has been undertaken, which can be seen in the appendix to this article.

Concentration in 1962

It is doubtful the original memorial panels were ever erected in Reshire – the ‘wait and see’ idea of ‘HFC’ in 1937 suggests that nothing would have been done before the outbreak of war in 1939. After the Second World War, the commission had a massive task in creating cemeteries and memorials for the dead of that conflict, and it is likely the tangled question of how to commemorate the dead in Persia took a low priority.

It probably became increasingly obvious the original cemetery and memorials in Reshire must have been deemed to be unmaintainable, and presumably after Indian independence the consulate office in Bushire was closed. The political situation in Iran during the 1950s was unstable, with attempted coups.[10]

All of this must have forced the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to the conclusion that the only safe location for a cemetery and memorial in Iran was in (or close to) the Embassy in Tehran. Ironically this was something that had been advocated by Captain Mungavin back in 1926.[11]

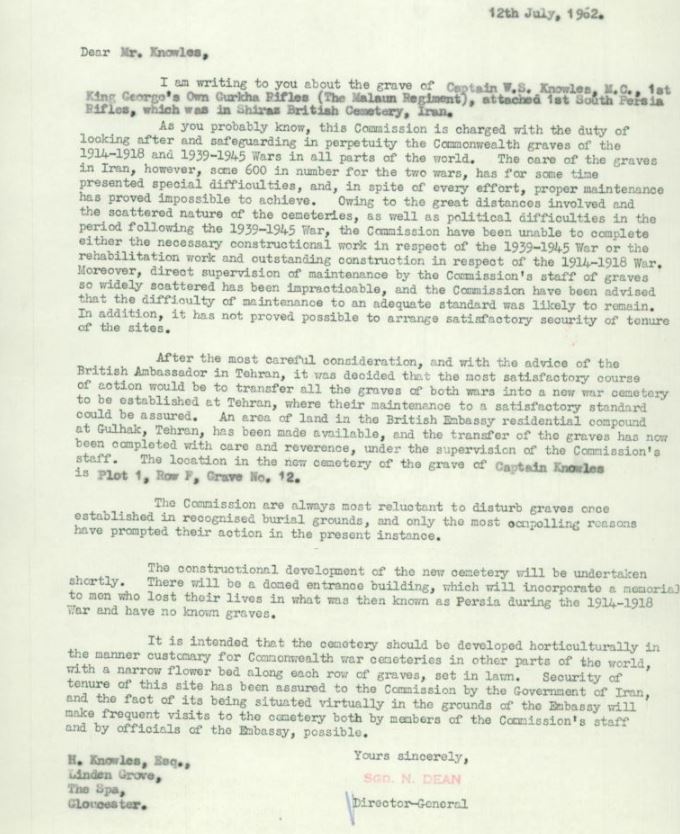

It seems a standard letter was sent out in 1962 to the relatives of those whose bodies were to be moved. An example of this can be seen below. It is clear that this is a proforma letter, with the name of the casualty and the location of the new grave inserted into the standard wording.

It is not clear if the memorial was built first and then the graves concentrated in, or the other way around. In any case, the Tehran memorial was built and the war cemeteries from around Iran were brought into ‘Gholhak Garden’ which is the UK’s compound in Tehran some seven miles north of the British Embassy. The garden is bordered by high walls, and covers 49 acres. It also houses British diplomats and their families.

The cemetery at Naibund forms the basis of the Addenda panel – but all the other names come directly from the original memorial at Reshire.

The 59 panels (plus the Addenda panel) now bear the names of those who have no known grave from the First World War.

As expected, the cemetery and memorial are kept in impeccable condition by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Appendix: List of sites of graves and Cemeteries originally created in Persia

Sources

Burials and Memorials of the British in Persia, Denis Wright. Source: Iran, Vol. 36 (1998), pp. 165-173 (Published by: British Institute of Persian Studies). URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4299982

Commonwealth War Graves Commission file WG219/30 [CWGC/1/1/9/C/34 (WG 219/30 PT.1) and CWGC/1/1/9/C/35 (WG 219/30 PT.2)]

Commonwealth War Graves Commission file WG597/5 [CWGC/1/1/7/E/45]

Mungavin’s report from 1924 was located in the CWGC online entry for Captain Allen Percy Adams

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Jill Stewart for creating the list of all Grave sites and Cemeteries.

Further reading

Dunsterforce:

References

[1] Monumental Inscriptions of Europeans in cemeteries in the Middle East and Africa [1938]. See https://archive.org/stream/cemet-middle-east-africa-images/CemetMiddleEastAfrica_djvu.txt

[2] In 1822, the Bushehr and Basra residencies were combined, with Bushehr serving as headquarters for the new position of "British Resident for the Persian Gulf."A chief political resident was the chief executive officer of the political unit, and he was subordinate to the Governor of Bombay until 1873 and after that, to the Governor-General of India until independence.

[3] The Indo-European Telegraph Department was a branch of the British Government of India, based in London, which managed a series of telegraph lines in Iran. It operated a telegraph line from Tehran to Tabriz and then across the Russian empire to Europe. The IETD was dissolved in March 1931.

[4] Commonwealth War Graves Commission file WG219/30. Report dated 14 October 1925

[5] Plus six Special Memorials for those from the Second World War.

[6] All Second World War fatalities killed in Iran are buried in Tehran War Cemetery although there are a number of ‘special memorials to graves that have been lost.

[7] While a definitive, universally accepted order of precedence is difficult to pinpoint, some key points can be identified. Regiments with the prefix "King's" or "Queen's" were generally given a higher rank in the order of precedence. Lancers were distinct from cavalry, and the "1st Duke of York's Own Lancers" was often considered the senior lancer regiment. The order was often determined by the numerical designation of the regiment, but regiments with the "Own" designation (e.g., "King Edward's Own Cavalry") were generally ranked higher than those without. Regiments with a strong historical record or connection to the British crown were also given precedence.

[8] Captain and Vice Consul Boxer who died in 1902, and Richard Laffere who died in 1909.

[9] Balochistan is a historical region in Southwest Asia, primarily populated by the Baloch people, and is divided between three countries: Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan.

[10] These forced the Iranian ruler Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (later the Shah of Iran) temporarily into exile, however he returned and remained in power until the revolution in 1979.

[11] It has not been possible to definitely identify Captain H St J Mungavin, but on the balance of probabilities he is James Henry St John Mungavin 1886-1966 (ex-Indian Army Reserve of Officers)

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles