The Armistice in Bijar and Dunsterforce in Baku

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Armistice in Bijar and Dunsterforce in Baku

The Armistice, which brought an end to the fighting in the First World War was, as everyone knows, signed on 11 November 1918. The news of Germany’s capitulation and the Kaiser’s abdication two days earlier led to banner headlines in newspapers and scenes of jubilation in many cities throughout the world. This, however, is just part of the story as a number of Armistices had already come into effect.

Armistice Day Celebrations in Toronto

Front page of The New York Times on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918

The Armistice with Bulgaria (the Armistice of Thessalonica) was signed on 29 September 1918 and the Armistice of Moudros with Turkey came into effect on 30 October. The Austro-Hungarians also concluded an Armistice on 3 November. Naturally, the news of these earlier armistices was greeted warmly, but without the rejoicing that took place after the German armistice. These other armistices would probably have hardy registered with the allied troops fighting in France – it was expected by many that the war with Germany would continue into 1919.

Perhaps one of the most out of the way places where British and Commonwealth troops were stationed was in Bijar (the city is in the north-west of modern day Iran, about 100 miles from the border with Iraq and about 600 miles south of the Azerbaijan capital, Baku.) An interesting account of the news of the Turkish capitulation being received in Bijar on 1 November, exactly 95 years ago, has been left in an little-known book by Major MH Donohoe.

Bijar was very excited by the intelligence that arrived on November 1st. We received an official notification that an armistice had been concluded with Turkey, at the request of the latter Power, and that hostilities were to cease at once. The Governor made an official call to offer his felicitations, and to congratulate the British on their triumph over another of their enemies. He dissimulated his real feelings with great artfulness, for while openly professing joy at our victory he was sorrowing in secret that a Moslem Power should have been overthrown by an Infidel. Still, he made the best of it, and candidly told some of his intimates who were inclined to be tearful because their religious pride had been wounded by the success of our arms, that the British, after all, had shown more real humanity and compassion in dealing with the oppressed Persians than ever had their coreligionists, the Turks.

The Governor having set the example in offering his congratulations, all the local notables were quick to follow, and they told us what, curiously enough, we had never realized before—that throughout the long-drawn-out War they had always ardently wished for the complete triumph of the British. We accepted their assurances, although finding it difficult to reconcile them with many of their actions when our military fortunes were not of the brightest.

An official communication was sent off by messenger to the Turkish commander, informing him of the armistice, and inquiring if he were prepared to abide by its conditions and order a cessation of hostilities on his side. But the enemy had evidently had the news as soon as we had, and decided to end the war then and there. When our messenger reached the Turkish position, it was only to find the place abandoned, the commander and every man having gone, leaving no address. The messenger trekked after them for a day, but their haste was so great that he was unable even to come up with their rearguard, so he returned to Bijar with the letter undelivered. And that was the last we heard of the Turk in the region of Southern Kurdistan.

Everybody in Bijar was now our sincere friend and well-wisher. The Bazaar was beflagged in honour of our victory. Ours was the winning side, of that there could be no doubt. The Governor was more assiduous than ever in his professions of undying devotion, and he was always planning fresh schemes for manifesting his goodwill and friendship. He even hit upon the expedient of declaring an amnesty for Persians incarcerated in the local gaol. At his urgent solicitation, I visited the prison to decide upon the offenders who were to benefit by this generosity. It was a filthy, evil-smelling hole. Lying upon a stone floor were about a dozen offenders, all huddled together and chained like so many wild beasts.

…In this foetid den… was a young Persian girl of attractive appearance—an unregenerate Magdalene, as it turned out, who had been put in chains for a breach of the somewhat elastic Persian law governing public morality. She alone made no protestation of innocence and no appeal for release. Perhaps that was why I suggested she should be the first to have her fetters struck off and be set free. She seemed dumbfounded at first, but on realizing that liberty awaited her, she burst into tears, and showed her gratitude by kissing my hand. It seemed a pity to leave the other poor wretches, however guilty they might have been, to rot in this terrible dungeon; so I availed myself to the full of the privilege of the amnesty and asked that all should be liberated.

With the Persian Expedition, Major MH Donohoe (London: Edward Arnold, 1919).

Portrait of six officers at the headquarters of Starne's Detachment (part of the Dunsterforce) at Bijar. They are from left to right: Major Fred Starnes, DSO, OBE, MID and Captain Samuel Thomas Seddon, MC, both New Zealand army; M Gasfield, French from Urmiah; Lieutenant Richard Henry Hooper, (originally 58th Battalion AIF), MC; Major Chaldecott, Imperial Forces; Captain Fisher, Canadian army. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

What a Commonwealth unit was doing here is a complex story, but involves a little known unit, headed by an officer who was the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling’s character “Stalky” in his book Stalky and Co.

Background of Dunsterforce

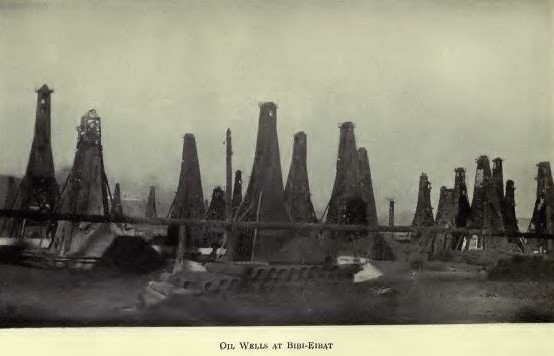

After the abdication of the Russian Tsar in 1917, the Russian Army was in a state of collapse. This left Central Asia open to the Turks. The British Government responded in 1918 with a plan to send a military mission, comprising less than 1,000 hand-picked Commonwealth troops (Australians, Canadians and New Zealanders as well as British soldiers were present). The intention was to send this mission to Persia and the group of countries to the north (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) to organise any remaining non-Bolshevik Russian forces who were ready to fight the Turkish forces. Georgian, Armenian and Assyrian people had supported the Russians and historically feared the Turks so it was hoped that these would be a source of recruits for the intervention. If successful, it was hoped that this would prevent German and Turkish troops capturing Baku (the capital of Azerbaijan – and the centre of important oil fields), entering Persia and threatening India.

Image from The Adventures of Dunsterforce (1920) by LC Dunsterville.

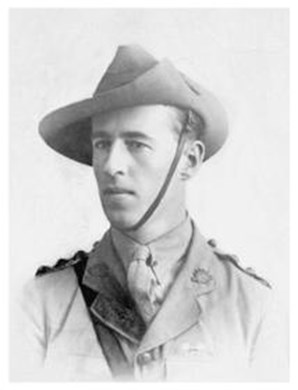

The force (39 Brigade) was led a Russian speaking British officer, Major-General Lionel Dunsterville and included twenty Australian officers, including Stanley Savige.

Major General Lionel Dunsterville (left) and Stanley Savige (right)

The country was in chaos, just one example is the fate of Urmia, in the extreme North West of Iran; this city was home to thousands of Assyrians and Armenians. Turkish armies attacked and plundered the city in June and July 1918. Thousands were killed, many more fled. Savige discovered tens of thousands of fleeing Assyrian refugees and, during the 5 and 6 August, deployed a small group of volunteers from his own force, along with refugees, to form a rear guard to protect the refugees.

Savige was subsequently decorated with the Distinguished Service Order. His citation read:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the retirement of refugees from Sain Kelen to Tikkaa Tappah, 26/28th July, 1918; also at Chalkaman, 5/6th August. In command of a small party sent to protect the rear of the column of refugees, he by his resource and able dispositions kept off the enemy, who were in greatly superior numbers. He hung on to position after position until nearly surrounded, and on each occasion extricated his command most skilfully. His cool determination and fine example inspired his men, and put heart into the frightened refugees.

Savige lost one man killed in this action, Captain Robert Kenneth Nicol, MC, of The Wellington Regiment, New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Nicol was killed whilst attempting to save the mules which enemy snipers were picking off. Savige later wrote a book about his experiences, Stalky's Forlorn Hope, which was published in 1920.

By August it was clear that the original mission, that of raising forces to keep the Turks at bay, had failed. Baku, with its oil fields, was in danger of falling into Turkish hands and Dunsterforce was ordered to advance to the city to prevent this. British forces dribbled slowly into Baku across the Caspian sea. The original Commonwealth contingent of less than 50 had grown to 900 by September, although this was still a small number compared to the Turkish force of between 12,000 and 14,000. The British troops’ main task was to advise and assist the 6,000 Armenian and 3,000 Russians who made up the bulk of the defenders of Baku. The problems they encountered were exacerbated by the hostility between the Russians and the Armenians.

One of the first British Army guns to arrive in Baku is manhandled down a gangplank into the port. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q24932

A British officer of the 'Dunsterforce' leading a drill for Jelu recruits. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q25024

On 1 September, Dunsterville had had enough. He told the local committee who were running the city:

“We came here to help your men to fight the Turks, not to do all the fighting, with your men as onlookers. In no case have I seen your troops, when ordered to attack, do anything but retire, and it is hopeless continuing to fight alongside of such men.”

Dunsterville informed the committee of his intention to evacuate, but was persuaded to stay.

A British officer from the Dunsterforce watches a Russian instructing a group of Persian police at Resht. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q24960

On the night of 13/14 September 1918, the Turks began their attack and although they were held up, it was obvious that it was only a matter of time before they would overrun the city. Dunsterville ordered his men to board ships and to evacuate. During the Turkish attack, only eleven fatalities were incurred by the men of Dunsterforce, although many more were incurred by the local population in the days following the British withdrawal.

A line of civilians queuing for their water ration in Baku in 1918. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q24912

Cemeteries and Memorials

The commonwealth casualties from the occupation and defence of Baku in the summer of 1918 were buried in Baku Cemetery (there were 45 burials from this period) but many of the original graves were lost after the Bolshevik occupation in 1920. In the years between 1920 and the early 1990’s the cemetery was built over. When it was realised that the graves in the area and elsewhere in the southern USSR could not be maintained, these 45 men were commemorated on the addenda panel at the Haidar Pasha Memorial in Turkey. This addenda panel commemorates over 170 men of the Commonwealth who were killed in South Russia and Transcaucasia and who were buried in around 15 different locations, and whose graves could not be maintained. One of these men was Colonel Pike who was shot on 15 August 1918 while observing street battles between the Bolsheviks and the Terek Cossacks.

Haidar Pasha Cemetery. Image courtesy of the CWGC

It was only after Azerbaijan gained independence that the CWGC was able to gain access to the area. A memorial was constructed to the 45 men who fell at Baku and two other men who were buried at Shusha Armenian Cemetery and whose graves were similarly lost. The Baku Memorial was made and ready by 1997 but was awaiting political agreement until 2002.

The Baku Memorial. Images courtesy of the CWGC

Other casualties from the Dunsterforce mission are buried or commemorated on the Tehran Memorial which is within the British Embassy grounds in the Iranian capital.

Tehran Memorial and Cemetery. Images courtesy of the CWGC

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice Chairman, The Western Front Association

Further Reading

A more in depth piece by Western Front Association member Harry Fecitt about Dunsterforce and the mission to Persia in 1918 is detailed on the WFA web site via this link.