Dunsterforce: The Fighting in North-West Persia During 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Dunsterforce: The Fighting in North-West Persia During 1918

The start of the Russian Revolution in the Spring of 1917 heralded the decline of Russia as an effective member of the alliance that was fighting the Central Powers who were led by Germany and Turkey. By December of that year revolutionaries had seized power in Russia and had signed a separate peace with the Central Powers at Brest-Livotsk. This resulted in the demoralisation and disintegration of the Russian forces that had been confronting Turkey in Anatolia and Persia. Turkey was now able to reclaim territory previously occupied by the Russians, punish those people such as the Armenians who had collaborated with Russia on Turkish soil, and look to expand Turkish influence both in the Caucasus region and eastwards.

The Caucasian states of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan created a Transcaucasian Federation that eventually declared itself to be independent from Bolshevik Russia in April 1918. Initially the Federation sought friendly relations with Turkey but agreement could not be reached on border demarcation and fighting commenced. This situation was compounded by Germany becoming involved on the side of Georgia, that state declaring itself independent from the Federation in May. Turks fighting Georgian troops found themselves fighting Germans who were assisting Georgia. Both German and Turkish eyes and interests were focused eastwards on the Azerbaijani oilfields at Baku on the Caspian Sea.

The Turkish War Minister, Ismail Enver Pasha, had ambitions to unite the Turkic people of Central Asia with Anatolian Turkey. On hearing of the fighting in Georgia, Enver quickly went there accompanied by the German Chief of the Turkish General Staff, General Hans Von Seeckt. Differences were resolved between German and Turkish policies in the region, and Enver ordered two weak Turkish armies to prepare to advance eastwards. The Ninth Army was to advance through Persian Azerbaijan with Tabriz as its immediate objective, whilst the Third Army advanced upon Baku to seize the oilfields there. Neither of these Turkish armies contained German troops; the Germans were busy concentrating a weak division at Tiflis and they watched Enver's eastern advances with interest but did not directly support them, preferring to thwart them where they could. But German training missions were already in Persia attempting to achieve a change of government that would bring Persia into the war as an ally of the Central Powers.

The British reaction

During the Autumn of 1917 Britain had observed the decline of Russian military capability on the Caucasian Front with deep concern. It was vital that Caspian oil and cotton (used in the manufacture of munitions) be prevented from getting into German hands. Britain also feared that the Central Powers would now move through neutral Persia (previously they had been restrained by an effective Russian military presence in the north of that country) to de-stabilise the Indian North-West Frontier and beyond, and bring Afghanistan into the war against Britain. Stability in India was a vital British requirement as a further half-million Indian soldiers were being recruited and trained at this time, with the aim of establishing 67 more infantry battalions, to be used primarily in overseas theatres.

Some modern historical commentators have derided this British fear. However during the war Germany promoted strong insurrections in Persia and infiltrated small groups of men and weapons through the country to Afghanistan; the Germans and the Turks did not need to move large armies through Persia, as well-led and financed training missions could achieve their aims. During the war German support for the Indian Ghadr revolutionary movement and Turkish calls for a Muslim Holy War caused serious problems in India and Burma, including mutiny in some military units. The Afghanistan threat was potent as was shown in 1919 when that country invaded India, encouraging thousands of border tribesmen to join in the fight against the British.

During late 1917 the War Cabinet in London wanted to move British troops into the Caucasus but none was available. An alternative plan was adopted to send a British Military Mission to the Georgian capital, Tiflis; this mission would not be a fighting unit but would contain instructors and staff officers capable of financing, training and organising indigenous Caucasian units that would fight the Turks. The only conventional part of the mission was to be a British Armoured Car Brigade. It was determined that the best possible route to Tiflis was overland from Baghdad through Persia to the Caspian Sea, then by boat to Baku, and onwards by train to Tiflis. Unfortunately events in Tiflis were already making this British plan redundant.

Command of the British Mission was given to Major General Lionel Charles Dunsterville CB. He was a well-liked and respected Indian Army officer and a fluent Russian speaker, with operational experience on the Indian North-West Frontier and in China. As Dunsterville states in his account of Dunsterforce, the name by which his mission became known: 'My own knowledge of the Russian language and known sympathy with Russia had probably a good deal to do with my selection for the task'. His mission was: 'the maintenance of an effective force on the Caucasus front so as to protect the occupied portions of Turkish Armenia and to prevent the realisation of Pan-Turanian designs'. The then British Military Agent in Tiflis was Lieutenant Colonel G D Pike MC, 9th Gurkha Rifles, Indian Army, and Dunsterville was to take over the appointment from him.

Above: General Lionel Dunsterville

Dunsterville's resources were a large treasure chest, the Armoured Car Brigade, a small group of staff officers, another small group of Russian officers, and around 200 officers and 200 non-commissioned officers selected chiefly from Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African units. Many of these men had been decorated for gallantry in the field. This was a Special Forces unit, tasked with a strategic Special Forces mission, long before Special Forces were officially invented, glamorised and awarded cult-hero status.

In the event Dunsterforce did not get to Tiflis, but it was involved in heavy fighting against the Turkish Third Army around Baku and in serious fighting against the Turkish Ninth Army and its Persian allies in northern Persia. This first article describes the important military actions in Persia, and a second article will describe military operations around Baku and the Caspian Sea.

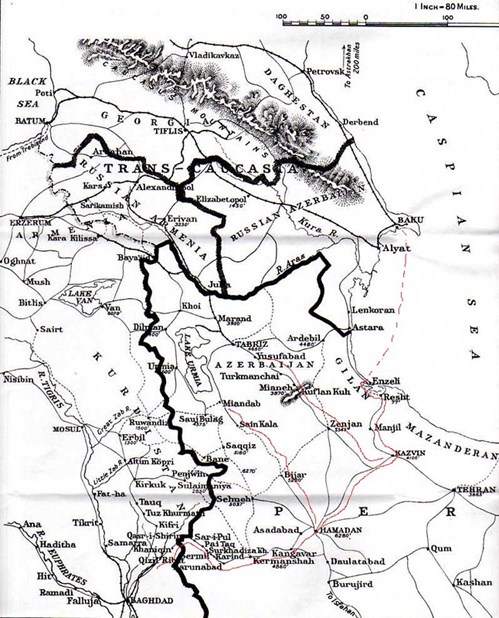

Map: Dunsterforce routes

Dunsterville moves into Persia

Lionel Dunsterville's first major problem was that he could not concentrate his mission before it was deployed; he set off himself first with a small staff hoping that his men and vehicles would quickly follow. In the event some parts of the Armoured Car Brigade did not arrive in Persia until after Dunsterforce had been disbanded. The second major problem was the attitude of the theatre commander in Mesopotamia, Lieutenant General W R Marshall KCB, who had succeeded in command after General F S Maude's death from illness in Baghdad. Marshall strenuously objected to the concept of Dunsterforce because he had to logistically support it across Persia, but more personally he vehemently objected to the fact that Lionel Dunsterville reported directly to London. From this moment onwards Marshall's somewhat petulant opposition to Dunsterforce grew and Dunsterville's chances of achieving some kind of success receded.

On 24 January 1918 Dunsterville despatched an advance party under Major Sir Walter Barttelot DSO, Coldstream Guards, who was accompanied by Captain G M Goldsmith, Intelligence Corps, and an armoured car commanded by Lieutenant C M Singer, Devonshire Regiment and Motor Machine Gun Corps. Barttelot's mission was to move to Hamadan in Persia and ensure petrol supplies for Dunsterville's group when it arrived. Three days later Dunsterville left Mesopotamia with 41 Ford cars with Army Service Corps drivers, eleven staff officers and two clerks. The drivers took rifles and an infantry staff officer took a Lewis Gun. Critically the convoy carried a large amount of Persian silver and British gold coins, and the need for adequate protection of this treasure was soon to constrain Dunsterville's actions.

After struggles through snowdrifts the 41 Ford cars reached Kermanshah on 3 February. Here Dunsterville made contact with 1,200 Russian Cossacks under the command of Colonel Lazar Bicherakov, a courageous and charismatic Ossetian who was to be a staunch ally of the British in northern Persia and the Caucasus. Bicherakov and his Caucasian Cossacks were fiercely anti-Bolshevik. Lieutenant Colonel C H Clutterbuck, 125th Napier's Rifles, Indian Army, was the British liaison officer with the Russians, and he was assisted by New Zealand army signallers manning a Russian wireless set. Clutterbuck was a Russian language specialist and popular with the Cossacks; the New Zealanders were from an Australian and New Zealand wireless squadron.

Above: Dunsterforce men (Australians in slouch hats) in Persia

Dunsterville pushed on the next day, now accompanied by one of Bicherakov's officers acting as a guide. Due to snowfalls the convoy did not reach Hamadan until 11 February, although Dunsterville rode ahead and reached the town four days earlier. Fortunately the road being followed was an ancient trade route and old serais, designed to shelter passing camel caravans, were located along the way. At Hamdan the advance party was waiting as was Brigadier General Offley Shore, CB, CIE, DSO, Indian Army, who was returning from Tiflis and waiting to brief Dunsterville on the current situation there.

Above: Dunsterforce camp at Hamadan

Also at Hamadan was the Russian Lieutenant General Nikolai Baratov, commander of the Russian troops in northern Persia. This force had performed well as part of the Imperial Russian Army and had pushed a Turkish advance out of Persia and back into Mesopotamia. But now Baratov's command had disintegrated and most of his remaining soldiers refused to accept orders as they tried to get home. Dunsterville carefully negotiated separately with Bicherakov and Baratov. He paid Baratov for items of military equipment purchased and he paid Bicherakov when he needed the Cossacks to fight.

Above: Dunsterforce car and driver

Whilst the convoy re-organised at Hamadan Captain Goldsmith was sent ahead again to reconnoitre the route to Enzeli and locate petrol supplies. In the event George Goldsmith then parted from Dunsterforce, as he successfully reached Enzeli on the Caspian Sea, took a boat to Baku and then the train to Tiflis where he joined Colonel Pike. After Geoffrey Pike was killed during a fight between Bolsheviks and Terek Cossacks in August 1918, Goldsmith became Acting Commanding Officer of the Caucasus Military Agency until he was arrested by Bolsheviks two months later; but long before those events Dunsterforce's mission had been re-focused away from Tiflis.

The advance to and withdrawal from Enzeli

Dunsterville left Hamadan on 14 February when a pass immediately ahead was cleared of snow and his convoy, now including Cecil Singer's armoured car, made good time down an excellent Russian-constructed road to Kasvin. This was an important town of 50,000 inhabitants and the road to Tehran, the Persian capital, forked eastwards from there.

Dunsterforce was now approaching territory controlled by a group of Persians known as the Jangalis because they operated from the heavily forested or jungle-like land in Gilan Province south of the Caspian Sea. The Jangali revolutionary leader, Mirza Kuchik Khan, had vowed not to let the British through his region. Kuchik Khan, like many Persians had felt humiliated by the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 that was used to allow 'Spheres of Influence' to be created in Persia, the Russian sphere being almost the entire north of the country and the British sphere being in the south-east, adjacent to the Indian border. So far the Jangalis had resisted attempts by both the Tehran government and the local Russian forces to destroy them. A German mission under Colonel von Passchen was training Kuchik Khan's men who were equipped with rifles and Turkish machine guns.

The British convoy drove on towards the Caspian on 16 February, pushing its way through hordes of Russian pro-Bolshevik soldiers who had demobilised themselves and who just wanted to go home with whatever booty they could carry. The convoy crossed the bridge at Menjil and drove on to Resht, not knowing that both locations would shortly have to be fought over. At Resht Dunsterville met with the British Acting Vice-Consul Charles Maclaren, who was soon to be captured and incarcerated by the Jangalis along with Captain E W C Noel CIE, 91st Punjabis, Indian Army attached to the Political Department. Noel would be carrying despatches from Tiflis for Dunsterforce at the time of his capture. The cars then drove to Enzeli on the Caspian Sea where trouble started to mount.

Above: A repair team works on a British armoured car

At that time Belgians managed the Persian customs for the weak Persian central government, just as Swedes managed the Persian Gendarmerie. The Belgians in Enzeli hosted the Dunsterforce convoy but Russian Bolsheviks controlled the port. After negotiations, which Dunsterville always preferred before military action because of the weakness of his force, the realisation came home that the convoy was not going to be allowed to board a ship and, even if it did, then the Bolsheviks controlling Baku would arrest Dunsterville and his men on arrival at that port. To stay in Enzeli was to invite destruction at the hands of Bolsheviks and Jangalis with the consequent loss of the treasure chests that were to finance anti-Central Powers military activity in the Caucasus. Dunsterville maintained good relations with the Bolsheviks controlling Enzeli, obtaining all the petrol he needed, and before dawn on 20 February his convoy was back on the road to Hamdan. Later that day a detachment of Red Guards arrived at Enzeli from Baku, just too late to accomplish its mission of arresting the British soldiers.

At Resht, Dunsterville learned that the reason why his convoy had not been attacked on the Enzeli-Resht road was because the Jangalis had been uncertain whether or not the withdrawing Russians would fight alongside the British. Overdue maintenance on the cars was performed at Resht under the supervision of M2/130904 Serjeant R W Harris, Army Service Corps, and then the convoy drove off to arrive back at Hamadan on the evening of 25 February. Dunsterville chose Hamadan as his firm base because of its strategic location within Persia and its healthy climate, and here he spent time explaining his intentions to the local Persian administrators and attempting to secure their support for his activities. This was a delicate task as Persia was still a neutral country and most Persians resented the constant intrusions onto Persian soil practised by both the Allies and the Central Powers.

Interlude at Hamadan

Dunsterville received orders through the Russian wireless station, from London via Baghdad, to remain where he was, monitor the situation inside Persia, and to advance when he could. When the snows melted more elements of Dunsterforce were marched up from the holding camp at Baghdad. Many more stores, particularly petrol, oil and lubricants were brought up. This was much to the exasperation of General Marshall who had to watch most of his motor transport being deployed into Persia, although as Commander of the Mesopotamia Theatre he was not being required to mount significant operational activity at that time.

A severe famine was prevailing in western Persia because of predations by Turkish and Persian troops during the previous years that were now compounded by the avarice of local speculative traders, and people were dying in the streets and barren fields. Cases of cannibalism in Hamadan were being reported. Dunsterforce embarked on a large programme of famine-relief work, employing Persians on civil construction projects, particularly road improvements. The South African Brigadier General J J Byron DSO was placed in charge of famine-relief operations, whilst the Canadian Lieutenant Colonel J W Warden DSO was appointed town Commandant of Hamadan, with Captain F P Cockerell MC, Intelligence Corps, as Assistant Provost Marshall.

Another activity was the recruiting and training of local levies and bands of irregulars; theoretically, the levies would be able to guard vulnerable points anywhere whilst the irregulars would defend their own villages. Major J J McCarthy DSO MC, Northern Rhodesian Police, and Captain R S Engledue, 89th Punjabis, Indian Army, were leading figures in this activity. Concurrently a British intelligence organisation was created under Captain Macan Saunders DSO, 36th Sikhs, Indian Army, and tasked with reporting Turkish movements. Meanwhile Turkish military instructors were busily at work training their own militias in villages surrounding Hamadan, and Russian troop movements were being attacked whilst British officers were occasionally sniped at from a distance.

After consultations, the new Chief of the Imperial General Staff in London, General Sir Henry Wilson, ordered in March that Dunsterforce was to frustrate enemy penetration through north-west Persia and that General Marshall was to be responsible for this, using Lionel Dunsterville as his local commander in Persia. Meanwhile in Baku the Bolshevik and Armenian defenders were resisting the advance of the Turkish Third Army and they were being assisted in this by German refusals to allow Turkish troops onto the Tiflis-Baku railway. In the southern Caucasus the situation deteriorated by the week as the Georgians became increasingly accommodating towards the Germans and the Turks began transiting through Armenia into Azerbaijan, and it was Dunsterville's opinion that only Allied military units and formations could influence the situation now - British instructors and gold would only complicate and exacerbate it.

Bicherakov now decided that as the snow was clearing he would take his men out of Persia to pursue anti-Bolshevik activities in the Caucasus, but Dunsterville persuaded him to delay the move, promising to support the Cossack march to Enzeli with British armoured cars and aircraft which were now flying into Hamadan. Meanwhile, to counter both the progress and the propaganda activities of the Turkish Ninth Army and German training teams in Persia who were proclaiming German success on the Western Front, Dunsterville sent out two small missions to both show the Allied flag and to search for tribal leaders who might be prepared to fight the Turkish advance from Tabriz. The New Zealander Major Fred Starnes DSO, the Canterbury Regiment, was dispatched to Bijar, 100 miles north-west of Hamadan whilst Major Lewis Wagstaff CIE, 2nd Queen's Own Rajput Light Infantry, Indian Army, pushed westwards along the Tabriz road from Kasvin. Starnes was also tasked with trying to make contact with a large Jelu community, the name given to a combined group of Armenians and Assyrian Christians that was isolated but successfully resisting Turkish advances around Lake Urmiah.

April saw more Dunsterforce personnel arriving in Hamadan, plus three more armoured cars from the 6th Light Armoured Motor Battery and 'C' Squadron 14th (The King's) Hussars, a British Regular Army cavalry regiment.

Above: 14th (King's) Hussars in Mesopotamia

In May Dunsterville visited Tehran to consult with the British Ambassador, and also that month the fourth and final party of Dunsterforce arrived in Hamadan accompanied by a group of specially selected anti-Bolshevik Russian officers.

The Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet in London made an important policy change on 27 May, telegraphing that Dunsterforce was now not to attempt to get to Tiflis but was to reach the Caspian Sea and take control of the shipping fleet there. The military priority was to secure the Mesopotamia-Enzeli road. This instruction was modified to allow Dunsterville or one or more of his officers to go to Baku, at General Marshall's discretion, to reconnoitre the task of demolishing Baku's oil wells. General Marshall was to find the troops needed by Dunsterforce. But Lionel Dunsterville was never to get the troops he needed to complete the tasks that he would undertake and by now many of his men were dispersed around northern Persia on intelligence, famine-relief and training duties.

Concurrent with Dunsterforce operations were a British military move into Russian Transcaspia from Meshed in north-eastern Persia and the military operations of the British-sponsored South Persia Rifles in the south of the country.

The road to Resht and the Menjil Bridge

On 1 June Dunsterforce moved to Kasvin, leaving Brigadier John Byron in charge of the line of communication at Hamadan where Lieutenant Colonel W Donnan, a re-enlistment from the Indian Army Retired List, was commanding an efficient militia. Kasvin was an unhealthy location and the Dunsterforce Senior Medical Officer, Major John H Brunskill DSO, Royal Army Medical Corps, soon had too many patients. An important arrival from Baghdad was Lieutenant Colonel J C M Hoskyn DSO, 44th Merwara Infantry, Indian Army; John Hoskyn became the Dunsterforce principal staff officer (GSO1) for Military Operations.

At long last a detachment of the Dunsterforce Armoured Car Brigade (known as DUNCARS) was nearing Kasvin. This brigade had been formed in England from a Royal Navy Air Service armoured car unit that had been serving in Russia until 1917. When this detachment arrived it would patrol the line of communication whilst Bicherakov seized Enzeli. However the movements of DUNCARS were restricted by a shortage of lubricants and spare parts in Mesopotamia and by the Rubberine tyres, designed for Russian cold-weather use, solidifying in the Persian heat and breaking back axles.

The attitudes of both London and General Marshall became more flexible over Baku in early June, both parties agreeing that Dunsterville could decide what force to send to Baku, but that General Marshall would retain overall command of Dunsterforce operations. But a week later the uncertainty over exactly what Dunsterforce was expected to achieve surfaced again when General Wilson in London expressed doubts about how long a British force in Baku could survive against a determined Turkish attack backed by the local Muslim Tartar community that was strongly pro-Turk and anti-Armenian; in the event this was a prescient comment but it displayed a difference in opinion between the Generals in London and the politicians on the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet. The British wanted control of the Caspian Sea, but they shied away from the reality that Baku had to be held by a military force in order to maintain that control; Lionel Dunsterville was left to make the new policy work as best he could whilst his military masters commenced distancing themselves from possible failure.

On 10 June, negotiations with Kuchik Khan to persuade him to become neutral having failed, Dunsterforce marched out to fight. Bicherakov's column consisting of two squadrons of Cossack cavalry and a detachment of infantry, a section of Russian mountain artillery plus 'C' Squadron 14th (The King's) Hussars, advanced towards Resht with the British squadron leading. In support were two British armoured cars and two British aeroplanes. At Menjil, half way to the Caspian, was a 200-metre long, 5-span girder bridge over the Kizil Uzun River that the Jangalis were defending with an estimated 2,000 men and several machine guns. However the Jangali defences were poorly sited and vital ground was not occupied despite the presence of Colonel von Passchen.

To test the determination of the defences the two aircraft flew overhead without firing and were met by widespread Jangali rifle fire. Bicherakov then led his men towards the bridge and dispersed a Jangali picquet by shouting and waving his stick at it. Von Passchen appeared under a flag of truce demanding a parley in an attempt to separate the Cossacks from the British troops but Bicherakov verbally dismissed him. Once von Passchen was out of the way the Russian gunners opened fire, the Cossack cavalry moved towards the enemy's right whilst the armoured cars engaged from his left and the infantry advanced. This caused the Jangalis on the near side of the river to flee from their trenches towards the bridge where many stragglers were captured. All the Jangalis now fled from their positions and Bicherakov's column pursued them for 16 kilometres towards Resht. Bicherakov and his Cossacks pushed on to Enzeli after reorganising, leaving detachments at Resht and two other points on the road. Captain A V 'Darkie' Pope's 14th Hussars guarded the Menjil Bridge.

Dunsterville needed to get more men forward from Hamadan before he could secure his line of communications whilst he advanced. General Marshall had sent forward a composite battalion, half 1/4th Hampshires and half 1/2nd Gurkhas, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel C L Matthews, Durham Light Infantry attached to and commanding 1/4th Hampshires. This unit was accompanied by Right Section (two guns) of 21st Kohat Mountain Battery (Frontier Force), Indian Army. The battalion and the gunners were titled 'Matthews' Column'. Some of the Hampshires now joined Dunsterville but the Jangalis, their morale recovered, gave them a warm welcome on 18 June by successfully ambushing a party on a small bridge at Siah Rud. Captain R C Durnford was killed and six men were wounded.

Three days later another successful Jangali ambush was sprung. For gallantry displayed on this occasion Lieutenant Geoffrey Watt, Motor Transport, Army Service Corps, received a Military Cross with the citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty between Menjil and Resht, Persia on 21 June, 1918. He was in command of a convoy of 66 vans which was heavily attacked by hostile irregulars. Eight vans were put out of action, but by his entire disregard of danger and good conduct he managed to salve them. Later, on three occasions he went out with a small party under fire and salved four more vans which had been abandoned.

Then the Gurkhas became involved and the fight-back began. On 29 June Captain Knightley Holler Coxe, Indian Army Reserve of Officers attached to 1/2nd Gurkhas, won a Military Cross at Imam Zadeh Hachem:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty near Stahmd Bridge, Persia, on 29 June 1918. He organised and executed a brilliantly successful attack on an enemy position, inflicting heavy losses on the enemy at very slight cost to his own force. He displayed marked ability and initiative, coolly meeting every contingency that arose with marked courage and skill.

The prominent use of Gurkha kukhris during this action gave the Jangalis something to think about but they were still prepared to attack as events in Resht during the next month showed. Elsewhere at this time there were reported to be around 2,000 Turkish troops in Tabriz, and Wagstaff's mission was ordered to establish itself at Mianeh and to patrol forward of there.

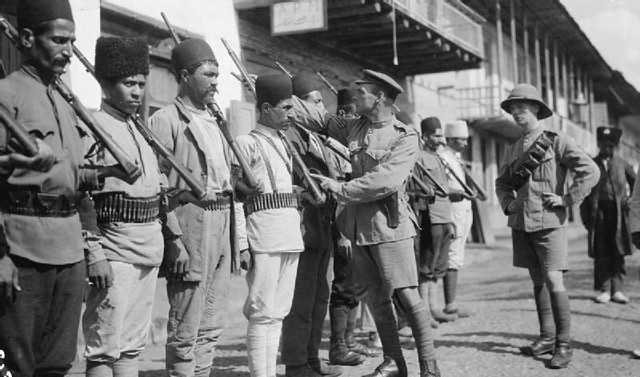

Above: A British officer from the Dunsterforce watches a Russian instructing a group of Persian police at Resht

Events in Baku

Dunsterville moved his headquarters forward to Enzeli appointing Major W S W Browne, 44th Merwara Infantry, Indian Army, to command British troops and levies in that town. The Resht area was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Matthews from a British camp sited just outside the town. London now became critical both of Dunsterville's perceived lack of action and of his failure to communicate regularly with Marshall. Dunsterville was expected to seize Enzeli by force from the Bolsheviks, and he was not to rely so heavily on Bicherakov who might prove to be untrustworthy. London impressed upon Marshall that now his most important area of operations was north-western Persia, as control of the Caspian was vital, and the British were contemplating purchasing the accumulated stock of cotton held in Krasnovodsk, the port opposite Baku on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea. A strategic assessment of Turkey's current war aims indicated that the Turks now accepted the loss of their Arabian provinces so they were attempting to compensate by moving eastwards into Turkic Asia. A further legitimate concern both to London, the Indian government in Delhi and the British Ambassador in Persia was that 38,000 Austrian and Hungarian prisoners of war held in Central Asia were being released and armed by the Bolsheviks.

To gain military control of the Caspian Sea, a Royal Navy party of 5 officers, 86 ratings and 12 guns suitable for mounting on the Caspian steamers was despatched to Enzeli from Baghdad under the command of Commodore D T Norris. Also the British 39th Infantry Brigade was now ordered to move forward from Mesopotamia to Hamadan; this move commenced but only gradually because of motor transport shortages.

Marshall described in detail his enormous logistics problems in supporting Dunsterforce but in a rather scathing tone. This prompted General Sir Henry Wilson to warn him privately 'that the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet thought I was not very zealous in carrying out their ideas and asked me to keep out of my communiques anything which might indicate an unwillingness to do so'.

Whilst Marshall was in India on leave Major General Hew D Fanshawe CB, the acting theatre commander, visited Dunsterforce from Baghdad after Dunsterville had visited him, and concluded that Dunsterville was doing the best that he could with the force he had. Fanshawe understood that there were different categories of Bolshevik and different shades of Bolshevism and that Dunsterville was correct to negotiate before using force, particularly as the Jangalis still held Edward Noel hostage. Lack of regular and detailed contact with Marshall was due to lack of adequate radio communications, but motor wireless equipment was being sent forward as were pack mules for off-road deployments. Fanshawe concluded by stating that so far Dunsterville had done exactly what he had been tasked to do – he had frustrated enemy penetration through north-west Persia and secured the land route from Mesopotamia to the Caspian Sea. Fanshawe also saw good reasons for sending troops to Baku; London concurred agreeing that two infantry battalions, an artillery field battery and armoured cars could be sent to Baku under Dunsterville's command.

Meanwhile Bicherakov had decided that his best tactic was to declare himself a Bolshevik so that he could gain a footing in Azerbaijan, and he accepted the post of commander of the Red Army in the Caucasus. He visited Baku where he found arguments developing between pro and anti-British Bolsheviks that Dunsterforce could exploit, then he returned to Enzeli to embark his men. Bicherakov's force sailed on 3 July accompanied by a few attached Dunsterforce staff officers and four British armoured cars.

Events now moved quickly. A British intelligence officer from the Military Mission in Meshed, Captain Reginald Teague-Jones, Indian Army Reserve of Officers, crossed the Caspian to Baku and on his return reported on the weak state of Baku's defences, and on the fact that the Germans in Tiflis were obtaining all the oil (through the Baku-Batum pipeline) and cotton that they could purchase in Baku. Information supplied by Ranald MacDonell, the knowledgeable British Vice Consul in Baku whom Teague-Jones had met, stated that many crews on Caspian steamers were anti-Bolshevik and that a British military presence was urgently needed in Baku to prevent the town falling to the Turks, but he advised against using force at Enzeli. When Bicherakov's Cossacks entered Baku pro-British sentiment was expressed by some important citizens in Baku, and on 26 July all the Bolshevik government members resigned to be replaced by a new government proclaiming itself to be Centro-Caspian and in need of British assistance.

Colonel Clutterbuck, the liaison officer with the Cossacks, informed Dunsterville of this about-turn by the Baku authorities but he also advised that Bicherakov was moving northwards towards Derbend. The Turks were holding ground overlooking Baku and were within 3,000 metres of the wharves. Bicherakov was not getting the ammunition and supplies that he needed from Baku and he was concerned about being tricked and trapped in that town. He suggested that Dunsterforce now land at Derbend, but that proposal was not acceptable to the British. Bicherakov, his British liaison and staff officers and three DUNCAR armoured cars under Captain W L Crossing DSC, Machine Gun Corps (Motors), marched north whilst the Turks inexplicably withdrew. As the Official History states: 'General Dunsterville offers the opinion that the movement northwards of Bicherakov's detachment, although apparently justifiable at the time, was a mistake which contributed mainly to the ultimate fall of Baku'.

Above: Terek Cossack Artillery

Thus Bicherakov regrettably marched away from Dunsterforce. From their first meeting in Kermanshah in February Dunsterville had realised how vitally important Bicherakov and his Cossacks were for the accomplishment of British strategy in the region, as Dunsterforce was not structured as a combat formation and initially it lacked artillery and cavalry. But others in more distant and peaceful offices did not share Dunsterville's appreciation.

But the future could not be predicted and Dunsterville, having obtained the agreement of the Enzeli authorities who were now friendly with the Centro-Caspians at Baku, rapidly organised a group of liaison and staff officers with an escort from the 1/4th Hampshires to sail to Baku. This group, under the command of the Dunsterforce principal intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel Claude B Stokes CIE, 3rd Skinner's Horse, Indian Army, reached Baku on 4 August. In the opposite direction the Russian linguist Lieutenant Colonel Reginald St Clair Battine, 21st Cavalry, Indian Army, went with a small group to Krasnovodsk on 6 August to establish relations with the anti-Bolshevik authorities there. Later in August a small mission was sent to Lenkoran, on the western Caspian Sea coastline, halfway between Enzeli and Alyat, at the request of its Russian community.

The fight for Resht

On 20 July around 2,500 Jangalis supported by a number of Turks and Germans under von Passchen attacked Resht. Colonel Matthews had with him 300 rifles from his 1/4th Hampshires, 150 Gurkha rifles under Captain G M McCleverty, 1/2nd Gurkha Rifles, two guns of 21st (Kohat) Mountain battery transported in Ford vans, and two armoured cars. Most of the British troops were in their base camp outside the town which was heavily attacked but detachments were inside Resht guarding buildings. At the base the enemy were driven back, leaving over 100 dead on the ground and 50 prisoners, including some Austrian and Hungarian former prisoners of war now released by the Bolsheviks, in the hands of Matthews' Column.

For gallantry displayed during this attack Lieutenant Henry Folliott Scott Stokes, 1/4th Hampshires, was awarded a Military Cross:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht, Persia, on 20 July, 1918. He went out constantly to the front line under heavy fire to report on the situation, sending back information of the greatest importance. Throughout the operations he carried on his arduous duties with remarkable zeal and daring. His services, rendered under trying circumstances, were of great value.

However and more seriously another large group of Jangalis had entered Resht and attacked the small British posts at the British Consulate, the telegraph office and the bank, which contained bullion. Colonel Matthews dispatched Captain McCleverty with 100 rifles and the armoured cars to withdraw the guards at the Consulate and reinforce the other posts within the town. This was easier said than done in the maze of alleys within the town and bitter street-fighting started that was to last for several days.

Two Military Crosses were awarded to officers of the Motor Machine Gun Corps.

Captain Geoffrey Noel Gawler:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Rasht, Persia, on 20 July, 1918. When his two cars were held up by a barricade across a road he exposed himself fearlessly in order to direct the demolition of the obstacle. Though severely wounded, he remained with his cars, eventually bringing them back safely. He only allowed his wounds to be attended to when he had made all arrangements for the despatch of his cars on another expedition.

and to Lt Cecil Mortimer Singer, Devon Regiment and 6th Light Armoured Motor Battery:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht, Persia, on 20 July, 1918. During an advance through a town he kept his car well in front of the column, and bore the brunt of the fighting in the narrow streets. In spite of heavy fire from rifles and bombs he pushed steadily on, and by his pluck-and determination performed exceptionally fine work. On a previous occasion, when his car was put out of action, he speedily repaired it, under most difficult conditions, and brought it into action again at a critical moment.

Another Military Cross was awarded to Subadar Major Tulsiram Gharti, 1/2nd Gurkhas:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht on 20 July 1918. During the attack by an enemy on a town he led his men with exceptional ability and dash, and by the rapidity of his advance inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, taking a number of prisoners. Later he displayed marked initiative and daring in the relief of a besieged garrison. His conduct throughout the operation was splendid.

Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded to 1200248 Corporal (Company Quarter Master Sergeant) D Kemp, 1/4th Hampshires:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht, on 20th July, 1918. During an enemy counter-attack the small party he was with became separated, and got engaged with a party of the enemy holding a house; after his officer (Lieutenant John Graham Wilkinson, 1/4th Hampshires) had been killed, and the majority of the men wounded, this N.C.O. assumed command, collected a few reinforcements, and skilfully withdrew his party.

and to 201830 Private (Acting Serjeant) F Mells, 1/4th Hampshires:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht, on 20th July, 1918, in command of a building heavily attacked by the enemy. His party held out for eight hours, inflicting appreciable losses on the enemy until a relief reached them. Serjeant Mells displayed fine qualities of initiative and leadership under trying circumstances.

Two men of the 1/2nd Gurkhas received Indian Orders of Merit. 3695 Havildar Kule Thapa:

He was in command of a small guard that was in a house surrounded by the enemy. Although heavily attacked and hard-pressed for nine hours, he beat off all attacks until relief arrived. He behaved throughout with the greatest coolness and resource, inspiring his men by his magnificent example. This non-commissioned officer has previously done good work in carrying out daring patrols and bringing back valuable information.

and 3966 Lance Naik Kuman Singh Gurung:

It was largely due to the skill and initiative with which this non-commissioned officer used his Lewis Gun that his platoon was able to advance as rapidly as it did. On one occasion when heavy enfilade fire from a house was delaying the advance, he left two men with a Lewis gun to give covering fire and with the remainder of his section rushed the house, killing a number of the enemy, including an officer, and taking several prisoners.

For the operations in Resht and at Imam Zadeh Hachem a month previously awards of the Indian Distinguished Service Medal were made to nine officers and men of 1/2nd Gurkhas: Subadar Aiman Rana; Jemadar Nandbir Thapa; 3489 Havildar Tilakchand Gurung; 199 Lance Naik Kalu Gharti; 3222 Lance Naik Maniraj Gurung; 1833 Lance Naik Balbir Rai; 1234 Rifleman Singbir Thapa; 455 Rifleman Kahar Sing Rana and 4535 Rifleman Jagia Khattrie.

Two men of 21st (Kohat) Mountain Battery also won Indian Distinguished Service Medals for gallant and resourceful actions at Resht: 403 Havildar Jaggat Singh and 152 Gunner Kishen Singh.

A Distinguished Service Order was awarded to Captain Guy Massy McCleverty MC, 1/2nd Gurkhas:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Resht, Persia, on 20 July, 1918. He was in command of a relief party sent to extricate a force besieged in a building. He displayed great courage and initiative, and it was mainly due to his resource and daring leadership that the relief was successfully accomplished. His work throughout the operations was of a very high order.

Lieutenant Colonel Claud Leonard Matthews, Durham Light Infantry attached to Hampshire Regiment, had himself been prominent during the fighting and he later received a Distinguished Service Order but without a published citation.

Matthews' Column had taken over 50 casualties but by the end of July Resht was cleared of all enemy troops and Kuchik Khan negotiated for peace; hostilities with the Jangalis ceased on 12 August. Attacks by the Martinsyde aircraft of 'B' Flight, No 72 Squadron, Royal Air Force, operating from Khasvin had been instrumental in demonstrating to the Jangalis that they could not compete with Dunsterforce. The British hostage Edward Noel was released, Vice-Consul Charles McClaren having escaped earlier, and Kuchik Khan became the largest contractor supplying rice for the British forces in Gilan Province.

The rescue of the Assyrian and Armenian Christians

Whilst Dunsterville was occupied with reinforcing Baku his men elsewhere in northern Persia were fighting Turks and their local allies. Fred Starnes had found a Turkish force at Sauj Bulaq that prevented him from contacting the Jelus at Lake Urmia. A temporary refuelling airfield was constructed at Mianeh that allowed Lieutenant K M Pennington to fly from Kasvin to Urmia where, on 8 July, he bravely landed unsure of who exactly was on the ground firing rifles into the air. The Assyrian ladies treated him with adoration as their saviour, and he arranged with the Jelu spiritual and military leader, Aga Petros, that a consignment of money, arms and ammunition would be available for collection from Dunsterforce at Sain Kaleh on 23 July. Kenneth Misson Pennington was to be awarded the Air Force Cross.

A Dunsterforce party under Captain S G Savige MC, 24th Battalion Australian Infantry, was waiting at Sain Kaleh on the due date; they had with them for Aga Petros a train of pack mules carrying £45,000 sterling in Persian silver coins, 12 Lewis light machine guns and 100,000 rounds of ammunition. But the Assyrians were late and the escort, two squadrons of 14th Hussars, who had been carrying quantities of the large silver Krans coins in their saddlebags, and a section from 15th Machine Gun Squadron, Machine Gun Corps (Cavalry), began to run short of grain for their horses. Despite Savige's objections Lieutenant Colonel E J Bridges MC, 14th Hussars, the escort commander, insisted on a withdrawal to Bijar but at the half-way point he permitted Savige and his party to remain at Takan Tepe and raise a levy from the local Afshah tribe.

Above: Gurkhas in Mesopotamia demonstrate new personal equipment

On 3 August Aga Petros and 2,000 of his men met up with Savige, but news of a disaster at Urmia quickly followed. Without Aga Petros' unifying presence many of the Armenians had suddenly deserted their positions facing the Turks and had fled with their families to British-occupied Mesopotamia. The 80,000 Assyrians had become demoralized by rumours of Aga Petros' defeat and death, and they fled towards Sain Kaleh. This allowed the Turks and their local irregular Kurdish allies to pounce on the fleeing Christians, killing thousands and seizing livestock, loot and young females for sale into slavery. The Assyrian rearguard was being led and inspired by two American Presbyterian Missionaries, Doctor William A Shedd and his wife Mary.

Above: Gurkha Vickers MG Team

When Savige and Petros met up with the fleeing hordes most of the Assyrian soldiers dispersed to look after their own families and interests, leaving the Dunsterforce team to organise the fighting withdrawal against the Turks and Kurds, along with the few Assyrians prepared to soldier alongside them. Captain Stanley George Savige MC was to receive a Distinguished Service Order:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the retirement of refugees from Sain Kaleh to Takan Tepeh, also at Chalkaman, 5 to 6 August. In command of a small party sent to protect the rear of the column of refugees, he by his resource and able dispositions kept off the enemy, who were in greatly superior numbers. He hung on to position after position until nearly surrounded, and on each occasion extricated his command most skilfully. His cool determination and fine example inspired his men, and put heart into the frightened refugees.

Captain Eric George Scott-Olsen, 56th Battalion Australian Infantry, received a Military Cross:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Sain Kaleh, Persia, on 6 August 1918, while assisting in covering the retreat of a party of refugees when the rearguard was heavily attacked. He held on to position after position, checking the enemy's advance. Heavy fighting lasted for six hours, during which he withdrew his party 15 miles while inflicting severe losses on the enemy. It was largely due to his courage and determination that the defenceless party were brought through safely.

A Bar to the Distinguished Conduct Medal was awarded to 1764 Serjeant B F Murphy DCM, 28th Battalion Australian Infantry:

For marked gallantry and leadership at Sain Kaleh. He was one of a small party covering a retirement, and by his courage and initiative in using his Lewis gun beat back determined enemy attacks. When his party were practically surrounded be gave his horse to a wounded officer and got away successfully with his gun on another. He showed splendid courage throughout.

The Distinguished Conduct Medal was awarded to the New Zealander 34906 Serjeant A Nimmo, 3rd Battalion the Otago Regiment:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Sain Kaleh on 6 August, 1918. He was with a small party detailed to cover the retirement of a column, and was left behind to bring the transport out of a village. He and another N.C.O. beat off a determined enemy attempt to capture the mules. Throughout the fight for fifteen miles he worked Lewis gun and rifle continuously.

Savige's team lost one man killed in action at Sain Kaleh, Captain Robert Kenneth Nicol MC, 2nd Battalion The Wellington Regiment, New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Robert Nicol exposed himself to enemy fire whilst gallantly attempting to save the mules which enemy snipers were picking off. His body could not be retrieved from the battlefield.

Above: Dunsterforce convoy near Birkandi

When the Dunsterforce team was being hard pressed at Sain Kaleh, Savige sent a messenger back to Bijar requesting support. The messenger was met by a patrol of 14th Hussars who immediately rode to assist. The patrol commander, H/47485 Serjeant A Hallard, 14th Hussars, received a Distinguished Conduct Medal:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty north of Sain Kaleh on 6 August 1918. While in command of a patrol he intercepted an urgent message from another party hard pressed by the enemy. After dispersing the enemy threatening his flank he led his patrol to this now exhausted party and relieved them. He displayed great promptitude and determination under trying circumstances.

The firepower of Albert Hallard's patrol pushed the Turks and Kurds back, allowing the refugee column to limp into Bijar on 17 August, but 30,000 Assyrians had been killed, captured or abandoned since they fled from Urmia. Also lost on the journey was the fighting American Doctor William A Shedd, who died of cholera whilst treating the many sick refugees. During the march to safety the Assyrians looted and destroyed every Persian village that they passed through, leading to the Dunsterforce team having to apply violent disciplinary measures to reduce these incidents.

At Hamadan the Urmia Brigade was established and able-bodied male Jelu volunteers were enlisted into its four battalions, under the supervision of Dunsterforce instructors; two battalions were Assyrian and the other two were Armenian. The remainder of the refugees marched down to a camp at Baqubah, Baghdad, the privations of this journey killing even more of them.

Turkish movement forward from Tabriz

On the 20 August Lewis Wagstaffe reported from Mianeh that Turks were advancing from Tabriz, where the Turkish 11th Caucasian Division was believed to have recently concentrated. This was unwelcome news as the enemy's intentions could have been to disrupt the British line of communication between Mesopotamia and the Caspian Sea. Wagstaffe had a platoon of 1/4th Hampshires and 650 levies with Dunsterforce instructors forward of the Kuflan Kuh ridgeline; in the rear at Zenjan there was the by now weak squadron of 14th Hussars and 50 rifles of 1/2nd Gurkhas.

Reinforcements for Wagstaffe were sent from Kasvin on 21 and 22 August. The artillery component consisted of a section each from the 44th and C/69th Field Batteries that had come up from Mesopotamia, and a section of 21st (Kohat) Mountain Battery. The infantry troops despatched were 100 more rifles from the Hampshires and 50 more from the Gurkhas. British air reconnaissance verified an enemy advance to Yusufabad, whilst a British intelligence report indicated that the Turks also proposed advancing from Sauj Bulag on the two roads through Saqqiz and Sain Kaleh. This intelligence assessment led to guns and infantry from 39th Brigade being held back at Hamadan and Kasvin, and this fact was to lead to a refusal of immediate reinforcements for Baku at the end of the month.

North Persia Force

As Dunsterville was now in Baku with a small tactical headquarters, General Marshall appointed Brigadier General A C Lewin CB CMG DSO to command all troops south of the Caspian Sea. Lewin took over the Dunsterforce main headquarters at Kasvin and commanded all operations in north-western Persia, reporting directly to Marshall.

By a subtle stroke Dunsterforce had been emasculated and the fall of Baku to the Turks had been ordained. But the real punch below the belt was that Marshall did not send staff officers from Mesopotamia for the new headquarters; thus when Dunsterforce was fighting for survival in Baku and Dunsterville was desperate for more staff assistance, he could not move his main headquarters forward to Baku as planned, as the men he needed were no longer under his command. That decision was now Lewin's and Lewin answered to Marshall. On 31 August Lewin, his task achieved, handed over his new command, titled North Persia Force, to the commander of 39th Infantry Brigade, Temporary Brigadier General H F Bateman-Champain CMG, 9th Gurkha Rifles, Indian Army.

The fighting along the Tabriz-Kasvin Road

On 5 September up to 2,000 Turks advanced from Yusufabad and engaged the British observation screen at Tikmedash. The British screen was commanded by Wagstaffe's second-in-command, a Dunsterforce officer named Captain H E Osborne, 2nd King Edward's Horse, and for his actions over the next three days Herbert Edward Osborne was awarded a Military Cross:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during a retirement from Tikmedash to Mianeh on 5-7 September, 1918. He conducted the withdrawal of his small command in face of strong enemy forces over a distance of 55 miles in a most skilful and cool manner. He caused the enemy many casualties, and eventually brought his force through to safety with comparatively few losses.

Osborne, who had previously reconnoitred up to the outskirts of Tabriz, had under his command locally recruited levies, stiffened by 'C' Squadron 14th Hussars (60 sabres) and small detachments of Gurkhas and Hampshires. When the Turks used artillery against Tikmedash the levies soon became demoralised and fled, as did the local mule train drivers who cut the loads loose and rode off on the mules. The Medical Officer Captain Jordan Constantin John, Indian Medical Service, attempted but failed to stop this flight although he did manage to evacuate the wounded, and he was later appointed Officer of the Order of The British Empire (OBE).

During the withdrawal from Tikmedash 1032 Lance Naik Sherbahadur Ghale, 1/2nd Gurkha Rifles, displayed gallantry that earned him an Indian Distinguished Service Medal. Osborne's next fight was at Turkmanchai a day later and here he was supported by the two mountain guns that had come forward; the mounted enemy unsuspectingly rode within range and suffered from accurately fired shrapnel shells. Here 4848 Lance Naik Bahadurman Rai, 1/2nd Gurkhas, also won an Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

Osborne's troops, now joined by Guy McCleverty who had reinforced him with 100 Gurkha rifles, reached Mianeh on 9 September. Here Claud Matthews had come forward to take command from Lewis Wagstaffe. A further withdrawal was made to a defensive position at the pass over the Kuflan Kuh ridgeline. Throughout the withdrawal from Tikmedash, 'Darkie' Pope's 'C' Squadron 14th Hussars had fought continuously as the rearguard, and it was due to the Hussars' professionalism that the Turks were held back, allowing the infantry to make clean breaks from the fiercely-fought actions.

The defensive position on the Kuflan Kuh was strong in artillery as the 18-pounders and the howitzers were in support along with a platoon of the 9th Battalion the Worcestershire Regiment, but with only about 60 sabres and 300 rifles there was insufficient infantry for Matthews to defend the feature satisfactorily. After repulsing a very determined enemy attack, during which his levies again fled whilst the Worcesters saved the day with a bayonet charge forward from their reserve position, Matthews ordered a withdrawal back to Zinjan.

Here the situation stabilised as the Turks had by now appreciated the firepower of the British artillery and of the armoured cars that had engaged them on the Zinjan road. Commonwealth War Graves Commission records suggest that two Serjeants of the Hampshires and two Gurkha riflemen were killed as the British pulled back from Tikmedash to Zinjan; all the British wounded were evacuated.

Captain R Goldberg, Machine Gun Corps Motors, had been prominent in operations against the Tabriz Turks. Reuben Goldberg was awarded a Military Cross:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Owing to his skill and ingenuity, a howitzer was brought from a distance of twenty-four miles into action against the enemy. On another occasion he carried out a reconnaissance over difficult country under fire, and brought back valuable information.

Reuben had previously fought in armoured cars in German South West Africa (now Namibia), and German East Africa (now Tanzania) and he was soon to be also awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

Conclusion

Hopefully what has been written so far sets the scene for the second part of the narrative that will describe events in Baku and around the Caspian Sea. Only the major actions resulting in gallantry awards have been described in this first part, but there were many more incidents when Dunsterforce levy commanders and Hussar patrols engaged both Turkish-inspired hostile tribesmen and gangs of bandits attempting to seize loot and females. Probably the full story of all these actions will never be told.

But the important fact, which was conveniently forgotten by the detractors who chose at the time to judge Dunsterforce operations as having failed, is that in northern Persia Dunsterville and his exceptional team achieved a remarkable success. Once the plan to reach Tiflis was abandoned Dunsterforce, utilising extremely limited resources, achieved the new mission of denying enemy movement through north-western Persia whilst securing the road from Mesopotamia to the Caspian Sea. General Hew Fanshawe, an honourable man who was never afraid of standing up to military authority on behalf of a deserving subordinate, was the only senior officer who appears to have appreciated the intricacies and complications of operating in neutral Persia; he commented objectively and accurately on Dunsterforce's success in northern Persia and on what was needed at Baku.

Endnote:

This account has concentrated on military actions at the expense of the concurrent international political activities, but anyone wishing to learn more of the intriguing political situation in the Caucasus and Transcaspia in 1918 will find a very readable and entertaining account in Peter Hopkirk's Like Hidden Fire. The Plot to bring down the British Empire.

Article contributed by e

Images contributed by Harry Fecitt and IWM

About the author:

Harry Fecitt joined the British Army in 1960, serving in the infantry. His first visit to Africa was as a paratrooper on exercise in King Idris' Libya in 1964. The following year he served on contract with the newly-formed Zambia Army.

In the early 1970s he was on contract with the Sultan of Oman's Armed Forces in Dhofar and later with the Dubai Defence Force.

Between contracts he served in the Territorial Army, mobilizing for 18 months to Belize in the 1980s, and after transferring to Intelligence in 1992 he mobilized again for four years for duties in the UK and the Balkans.

After parting with the military in 2002 he worked as a security contractor in North, East and West Africa and Iraq.

Harry retired to the Portuguese island of Madeira, and enjoyed researching and writing about colonial campaigns, particularly those that occurred on the African continent.