For the Fallen - the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in many lands

- Home

- World War I Articles

- For the Fallen - the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in many lands

Whilst it is unimaginable for any battlefield tour not to include at least one cemetery, the sad fact is that all too often many commercial tours degenerate into simple ‘ABC tours’ (‘Another bloody cemetery’) which follow a predictable list of cemeteries and specific graves. Obviously these graves have a story attached but the range and variety of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission is so great that sadly the great majority of cemeteries are rarely visited by the mass of visitors and all too often the global reach of the CWGC is forgotten.

With over 2,500 constructed WWI cemeteries and memorials in 107 countries, the CWGC provides a unique reflection of the global nature of the conflict and in 2012 I was honoured with the remarkable opportunity to take the photographs for the CWGC centenary book. It was a daunting task as in 2007 Brian Harris had produced the stunning Remembered: The History of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which had ranged the world and my immediate task was to follow in his footsteps. The commission dove-tailed with my own work documenting the landscapes of the WWI battlefields for my ‘Fields of Battle, Lands of Peace’ project so I resolved to try and show how the universal headstone fitted into the different landscapes around the world by showing the wider context of their surrounds.

Obviously no coverage of the CWGC would be complete without a photograph of Tyne Cot and for me, and no doubt countless others, the words of King George V (or were they Kipling’s as some suggest) when he said, ‘I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war’ were a summary of one’s feelings at this place.

I could not think of how to capture the spirit of those words until one day I was fortunate enough to capture a rare snowfall as dawn was breaking.

1: Tyne Cot

I was also blessed to encounter an obliging gardener who was in no way unnerved when a seemingly demented photographer appeared out of the swirling snow and begging that he remove his bright green tractor and himself from the cemetery lest he left any tracks in the snow. It was the first of many encounters with obliging CWGC gardeners and the discovery that the CWGC have an extraordinary ability to retain staff, not just for a lifetime but for other generations as well.

At Ramleh in Israel, I met Ibrahim Khoury and his sons, Issa and Johny, who have clocked up over 100 years of service and the only sad thing was that Ibrahim’s father was unable to join them for the photograph as then three generations of gardeners would have been present.

2: Ramleh Cemetery was created by the Australian Light Horse Brigade in November 1917.

Close by the city wall of Jerusalem, adjacent to the Temple Mount,lies the Bab Sitna Masriam Muhammedan Cemetery with its memorial to the 198 men of the Egyptian Labour Corps who are buried here.

3: The Egyptian Labour Corps memorial at Jerusalem.

All too often we forget the involvement of peoples of all faiths and nations in the war as witnessed by the cemetery at Arques-les-Batailles where men from the Chinese and South African Labour Corps are the majority of the almost 400 men buried there.

4: The dates on these headstones suggest that these men died either from Spanish Influenza or possibly from injury caused whilst clearing munitions from the battlefields.

The CWGC manages to instil its gardeners a real pride and love for their work and even in the remotest of places they are ever diligent and watchful. I had hardly walked into the lovely Morogoro Cemetery in Tanzania before Shamrock Paull the gardener appeared to see if he could help me. Although we had no common language, when he understood the purpose of my visit he persuaded his wife Lusia to overcome her shyness and be photographed.

5: The quiet pride of Shamrack Paull and Lusia Axalte is reflected in the immaculate beauty of Morogoro Cemetery.

In south-western Africa in the arid Namib desert lies Trekkopje, one of the smallest and most remote CWGC cemeteries in the world. Just a handful of graves, seven South African and seven German, all the result of fighting around the railway station in April 1915 which is now marked by just a weathered sign-board.

6: Trekkopje cemetery is marked by the tree to the right of the sign.

Sometimes it was essential to find the local gardener as at Buff Bay in Jamaica where I was fortunate enough to be taken by the local stone-mason to the only CWGC grave, which he tended immaculately, amidst a profusion of tropical vegetation. I think it is also the only time that I have drunk raw rum before breakfast.

7: Calvin Hill, local stonemason and purveyor of fiery rum at Buff Bay.

Indeed hospitality is a feature of CWGC crews: in Gallipoli at Hill 10 the team insisted that I shared their tea with some delicious flat-bread and cheese. For me, their hospitality was a reminder of those words of Kemel Attaturk when he assured the families of the men who had invaded and died in his land that

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side, here in this country of ours….Your sons are now lying in our bosom, and are in peace.After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.

8: Gardeners breakfasting at Hill 10 Cemetery

Sometimes the simple wording on a headstone can let loose a whole variety of questions. Amidst the 600 graves in Grangegorman Military Cemetery in Dublin is a headstone to Margaret Naylor, ‘Shot crossing Ringsend Drawbridge, 29th April 1916’. Clearly an innocent victim of the Easter Rising who just happened to be killed on the same day as her husband, Private John Naylor, No. 14578, was killed in a gas attack at Hulluch whilst serving with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Here in a few simple words is an illustration of the Irish dilemma and the question that sprang to my mind was which side fired the fatal shot - British Army or Irish Republicans. Whichever this was an awful tragedy and one wonders if there were small children.

9: A family tragedy revealed in Grangegorman Military Cemetery, Dublin.

Some headstones have well known stories already attached: the grave of Edward Brittain in the lovely tree-girt cemetery of Granezza on the Asiago plateau is just such one. As a guide I always find my voice falters when I stand there reading the words of his sister Vera Brittain as she describes how, on the day that the news of his death in June 1918 reached his home, ‘ the sad searching eyes of the portrait were more than I could bear, and falling on my knees before I began to cry, “Edward! Oh Edward!” in dazed repetition, as though my persistent crying and calling would somehow bring him back’. Vera Brittain wrote that "...for nearly 50 years much of my heart has been in that Italian village cemetery” and her ashes were scattered on her brother’s grave.

10: Granezza on the Asiago plateau

Oddly enough, after Granezza the next headstone I photographed was that of ‘D. Grant. Deck-hand, H.M.S. Vernon’ who died in May 1916. Its rugged grey granite was at one with its site in the ancient burial ground on St. Finnan’s Isle set in the middle of Loch Shiel in the Scottish Highlands. Only accessible by boat it is a reflection of the extraordinary variety of CWGC sites and the myriad problems of access and maintenance.

11 & 12: The granite headstone for D. Grant and St. Finnan’s Isle.

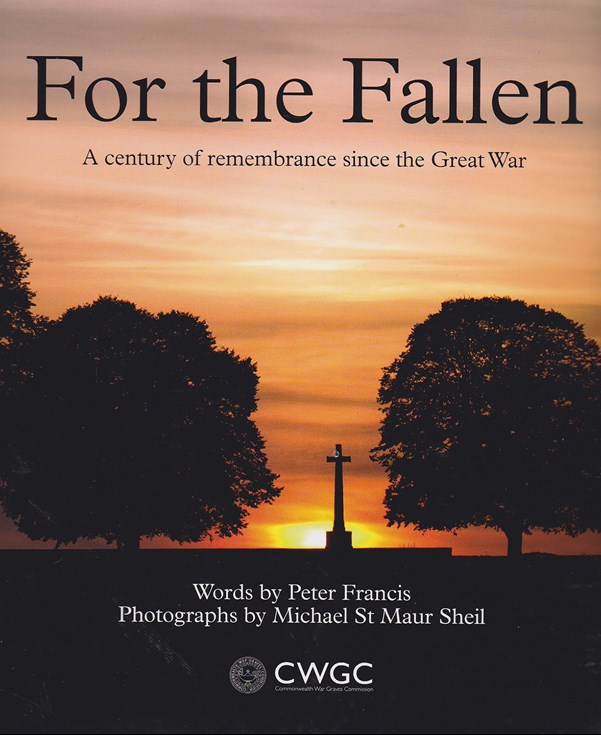

The Somme has so many extraordinary cemeteries. It was at Courcelette, as the sun was setting, that I slithered into a very fresh, stinking cowpat in my hurry to get my shot. I cannot recommend photography in ones underpants in the middle of a herd of cows but it was worth it as the shot appeared as the cover of the book.

13: Sunset at Courcelette.

Every cemetery on the Somme has its specific story: the great mass of the Lonsdale, set on the plateau above Authuille and largely ignored by the majority of visitors, tells of the losses.

14: Lonsdale Cemetery contains over 1,500 casualties.

The lonely grave of three Royal Fusiliers in the field above Faffemont Farm brings to mind the words of Charles Douie in ‘The Weary Road’

‘They sleep, many of them on the uplands of France.

They asked for no reward, no sunlit fields of heaven.

They played a man’s part, and held their heads high, till Death came in a roaring whirlwindand one more little hour was played.

Yet perhaps, as they sleep, they hear a voice across the ages ... “Well Done”.’

15: The battlefield burial site at Faffemont Farm.

There is Grandcourt, set like glowing jewel amidst a sea of fields, which bears tribute to the force and penetration of the Ulster Division attack on 1 July.

16: The isolated Grandcourt Road cemetery.

At Mametz the simple statement that ‘The Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still’ is attested in a letter written by Padre Crosse, to a wounded officer.

‘My Dear Babe,

So our game of tennis will have to wait for a bit....The total loss is heavy. Martin, Hodgson, Holcroft, Rayner, Riddell, Adamson, Hirst, Shepherd have all gone to their long home...Nearly all the casualties were just by the magpies nest. I buried all I could collect in our front line trench’.

17: The ‘Devons’ in their trench-line cemetery at Mansell Copse.

In the Ypres Salient I was fortunate that repair work on the Menin Gate afforded the unique opportunity of access to the roof enabling the unique perspective of an aerial shot of the Last Post ceremony.

18: The Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate.

It also gave me an insight into the CWGC’s continued instance on nothing but the highest standards of craftsmanship and attention to detail with brass-work, far from the public gaze, being restored to its original state using traditional methods and hand casting techniques.

19-Repairing the door of a Register Niche.

The Cambrai Memorial at Louverval, decorated with the magnificent bas-reliefs of trench life by Charles Sergeant Jagger are a prime example of the CWGC’s insistence on using the finest artists. Jagger had a notable war record, being wounded three times and winning a Military Cross, he stated that his "experience in the trenches persuaded me of the necessity for frankness and truth”. This desire for reality is revealed on one of the bas-reliefs by the tension in the hand of a wounded man, grasping the stretcher being lifted by two straining stretcher bearers.

20: Jagger’s detailed bas-reliefs honour over 7,000 men who are commemorated on the Cambrai Memorial at Louverval.

If a CWGC cemetery other than Tyne Cot should be regarded as an essential experience for the battlefield visitor, it must surely be St. Symphorien near Mons. In a unique way it encompasses so many elements of the conflict. Originally created by the Germans to bury their own and British dead in August 1914 it is laid out in the varied levels of an old quarry and is surely one of the most beautiful cemeteries along the Western Front. Lieutenant Maurice Dease, who was awarded the first V.C. of the war for his defence of Nimy Bridge, is buried not far from Musketeer Oskar Niemeyer who received one of the first German Iron Crosses for his swim across the canal to close a bridge. Here too is Private John Parr, the first British soldier to be killed by enemy action, along with George Ellison and George Price who were probably the last Commonwealth soldiers to be killed on 11 November.

21. St. Symphorien near Mons

For me, this was an ever memorable, if sometimes emotional, assignment which took me 18 months to complete and the CWGC, in the form of Peter Francis, who was then their Media Director, proved the ideal client allowing my total freedom to shoot in whatever manner I chose.

In all, I visited almost 400 cemeteries in over 20 countries but I have no hesitation in naming the one I would most like to revisit. Set miles from any road in the remote hills of Saskatchewan, Canada, Neidpath (Pollacks) Cemetery is by a long abandoned farmstead. On a hillside, amidst the wind rippled grass, are two headstones, one of them a CWGC headstone to Private Donald A Pollack who died on 15 November 1918, aged 25. He died of Spanish influenza and buried just feet away is his twin-brother Alexander.

Alexander and Donald, born the same day - died the same day.

One can only imagine their Mother’s joy as she welcomed her son home, safe from the war, only to see him sicken and infect his brother and then nurse them as they both drowned in their own phlegm. What must she have felt as she watched her sons die in such a remote place, far from help?

Standing there on that hillside, one has no need of a ‘massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war’ to remind one that

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

For me, that lonely, windswept grave-site epitomises, not just the misery and suffering of war, but all the amazing care and effort which the CWGC expends to ensure that the names of Pollock and Neimeyer, Dease and Price and so many men of so many nationalities will indeed ‘liveth for evermore’.

22: The Pollock brothers and their isolated resting place.

Article by Mike St Maur Sheil

Mike St Maur Sheil MA, FRGS is a photographer who created the series of multi-national exhibitions entitled Fields of Battle, Lands of Peace and who now regularly guides for Battlehonours Tours.