Here come the girls! The women volunteers at the Army Pay Office Woolwich from August to October 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Here come the girls! The women volunteers at the Army Pay Office Woolwich from August to October 1914

Abstract

August 2014 will witness the centenary of the start of the First World War. It is considered that much of the historical aspect will be focused on the all-male fighting army, with little attention being paid to the women's contribution during the course of the war. Yet also in August 1914 the first women to volunteer for the war effort made their presence felt in perhaps the least researched part of the British Army, the Army Pay Services, which has remained merely a footnote in history. The role played by the women volunteers at the Army Pay Office, (APO), Woolwich during the early months of the Great War is evidenced by the expansion of a Regular and Regular Reserve Army from a peacetime strength of 200,000 in August 1914, to nearly 1 million by November 1914.

The deployment of women volunteers at APO Woolwich was totally unofficial and was not part of any directive from the War Office. However, there had been a tradition of voluntary philanthropic assistance during the 19th century from military officers and their wives that supported the families of soldiers. This influence of regimental philanthropic assistance increased during and after the Crimean War. The women volunteers who assisted at the Army Pay Office Woolwich as it reorganised from peace to war were an extension of the tradition of regimental philanthropy.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate the origins of women's entry into Army Pay Department (APD) establishments during the First World War. By January 1919 there were over 28,000 women employed as temporary civil servants within the Army Pay Services. It is considered that an exploration of the army pay services generally, and of the women civilian staff in particular, is crucial to our understanding of the First World War. Pay and allowances were fundamental to maintaining the morale of the fighting army whose numbers peaked at 5 million by 1918, yet little attention has been paid to these women and the work of the Army Pay Services generally. For example, Winter and Prost (2005: 95) have noted that the British Army was the only military force from the belligerent nations that avoided mass mutiny, despite the militancy of the British working-man immediately prior to 1914. According to Winter and Prost the reason for the loyalty of the British Army during the Great War is still an open question.

Previous research into the morale of the British Army during the Great War has tended to focus on the regimental system. Baynes (1986), in his analytical history of the 2nd Battalion of the Scottish Rifles, (The Cameronians) from 1913 to 1915 focused on the structure of the regimental system and the influence it had on morale. The theme of the regimental system and morale is a favourite topic with military historians, notably French (1997) and Strachan (2000). One reason given for this loyalty during the Great War that was the efficiency of the Army Pay Services, which meant that the soldier received his pay on time and knew that his family was provided for through a series of family allowances that were reformed both in scope and depth during the first weeks of August 1914. A major factor that ensured the smooth running of APD establishments was due in no small part to the official employment of women within these establishments.

However, in August 1914 a number of women unofficially volunteered their services to the Regimental Paymaster at the Army Pay Office (APO) Woolwich. These women volunteers called themselves the 'Boy Girls of 1914' and possibly represented some of the first women to be engaged in war-work. Women clerks were not an official feature of army pay offices in the United Kingdom until January 1915, despite an earlier call by prominent members of the National Union of Women Suffragette Societies (NUWSS) for the government to employ women in all government offices for the duration of the War (The Spectator 12 September 1914). The APD establishments were possibly the first gender-integrated military units outside the realms of military medical units. The experience of the unofficial women employed at the Army Pay Office Woolwich as interpreted from the 'Boy Girls' article suggests that there was a gender/power influence. Women were officially recruited for duties within the War Office Finance Branch, Whitehall in November 1914 and in all APD Departments including army pay offices from January 1915 as previously noted. However, women volunteers were locally accepted on an unofficial basis to assist at the Army Pay Office Woolwich from August 1914 into what had otherwise been an all-male bastion. This paper traces the history and experiences of the Boy-Girls of 1914 in their contemporary setting.

The Army Pay Services on the Eve of the Great War

Prior to the commencement of World War One there were some twenty-seven army pay offices throughout the United Kingdom and Ireland. These army pay offices were responsible for the maintenance of pay and allowances of soldiers of the Regular Army and its Reserve, the Territorial Force and Special Reserve. The APOs were also responsible for the administration and payment of military pensions. The total of these elements that constituted the British Army was about 200,000. Command Pay Offices (CPOs) were located in home commands and their role was different from that of army pay offices: it included being responsible for the audit of accounts, pay sheets and expense claims, and the authorising and payment of civilian contractors' bills for work incurred by military units within their command. The Command Pay Office London District also fulfilled an APO role, being responsible for the accounts of the Brigade of Guards and Territorial Force establishments within the London County Council area.

The strength of the Army Pay Services in 1914 was 1,070 comprising all ranks (all male) made up of 180 paymasters commissioned into the APD and 890 warrant officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) of the Army Pay Corps (APC) (The Souvenir, 1920: 2). The salaries of commissioned officers of the Army were administered through civilian army agents. Command Pay Offices acted as a link between the army agent and the War Office Finance Branch.

The structure of army pay offices was based on fixed centre pay offices, each being responsible for a number of corps and regiments in the British Army. If the soldier moved to a new establishment or was mobilised for war, the respective APO remained within its static location in the United Kingdom. This system was known as the 'Dover' system, so named because a pilot scheme had been conducted at the experimental Army Pay Office at Dover (responsible for the accounts of the Royal Garrison Artillery) between 1904 and 1905. The Dover system remained the structure of army pay offices until the last decade of the 20th century. Most pre-1914 APOs were small, having no more than thirty military staff comprising of APD officers and APC warrant officers, NCOs and soldiers. The pre August 1914 Army Pay Services establishment in the UK also employed civilian male clerks, a number being retired members of the APC. The Army Pay Services also employed civilian boy writers for clerical duties in their UK establishments.

By 1914 APO Woolwich was the largest army pay office, having a military staff of ninety, and was responsible for the administration of 60,000 personal accounts. It was located at Woolwich Dockyard, which had been transferred from the Admiralty to the War Office in 1875. The Woolwich Army Pay Office was responsible for the accounts of soldiers serving with the Army Service Corps (ASC); the Army Ordnance Corps (AOC); the Army Veterinary Corps (AVC), and the APC, as well as the accounts of the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) and the Royal Field Artillery (RFA). The ASC was the largest logistical corps in the Army, and the RHA and RFA were the largest regiments.

Other military units also located at Woolwich Dockyard included the Record Office of the ASC and the AOC, together with an Ordnance Depot. The Ordnance Depot had a major bearing on the origins of the women volunteers at APO Woolwich. Record offices were also relatively small and their role was to maintain the personal records of soldiers in terms of career advancement that included promotions / demotions, skill and trade qualifications that resulted in pay increases or decreases. The record office was the authorising agent to notify the pay office of such changes in rates of pay. Other duties included the maintenance and updating of personal records for soldiers, and posting and transfer of soldiers. Another duty of the record offices included the maintenance of both establishment strengths of units and until August 1914 of the regimental marriage establishment. The suspension of the married establishment was the backdrop behind the origins of The Boy-Girls of 1914 at APO Woolwich, particularly during the first hectic weeks of August and September 1914.

Sources

There are no surviving personal records of women who were employed as temporary civil servants for duties with the Army Pay Services during the Great War. The experience of the Boy-Girls of 1914 was discovered in a pamphlet located in the Library of the Imperial War Museum (IWM) called The Souvenir, a 20-page pamphlet that records the history of APO Woolwich from 1914 to 1920. Contributors to The Souvenir included women and male civilian staff including military members of the Army Pay Services. Of particular note is an article of some two pages called 'The Boy-Girls of 1914' which appears in The Souvenir (pp5-6). The author's name remains anonymous and can be identified only by her initials of 'KFK'. There are hints in this article that suggest KFK was one of the original women volunteers of 1914. The article also suggests that KFK and other original members returned to APO Woolwich in 1915, when women as temporary civil servants were officially recognised by the War Office.

However, there has been excellent in-depth research conducted into the experiences and roles of working-class women who were temporarily employed in the engineering and munitions industries during the First World War (Braybon, 1981; 1986; Thom, 2000). By contrast however, there has been less research undertaken related to 'white blouse' women employed within contemporary government departments. This point was emphasised in the editorial of The Souvenir, written by two women editors who called themselves the 'editorists', Miss F Hitt-Salter and Miss F Potts. The editorial remarked that the story of the APC 'girls' had been neglected despite contemporary written histories of other women workers and volunteers during the Great War. The editorial stated that:

'During the war, and since the armistice, eulogies have been written to the women of Britain, particularly the Munition Workers, the VADs [Voluntary Aid Detachments of the British Red Cross Society], the WRAFs [Women's Royal Air Force]; Wrens [Women's Royal Naval Service] and WAACs [Women's Auxiliary Army Corps]. (The Souvenir, 1920: 3)

The last three, representing the uniformed women's branches of the armed forces, had been very formed in 1917 some three years after the commencement of war. The women volunteers began working at Woolwich army pay office some nine months prior to the arrival of the first women munitions workers at the nearby Royal Arsenal during the summer of 1915. Therefore the Boy-Girls of 1914 were perhaps the first women volunteers of the Great War. Within The National Archives (TNA) at Kew there are copies of the contemporary King's Regulations (KRs) of 1913 and the Manual of Military Law (MML) of 1914. There is also a file related to the History of Separation Allowances during the Great War (TNA WO 32/9316). Although this document does not mention the women volunteers, it does indicate that women clerks were recruited for employment in the War Office Finance Branch from November 1914.

There tends to be little in the way of secondary source material, possibly because historians have generally ignored the role and history of the Army Pay Services, a point raised earlier. Hinchliffe, a retired senior officer, wrote a narrative history in 1983 of the Royal Army Pay Corps (RAPC). He devoted two chapters of his book to the history to the Army Pay Services during the Great War. Despite this, Hinchliffe only included three lines focusing on the role of women employed with APD establishments from 1914 to 1920 (Hinchliffe, 1983: 66). This neglect has been partially redressed by Black in two recent publications (2006 and 2008).

In her research, Zimmeck undertook research focused on women employed in clerical work in 1986. Her thesis explores the lives of women employed by The General Post Office (GPO) and its subsidiary the Post Office Savings Bank (POSB) from 1870 to 1914. During this period the state was the major employer of women, and their employment in a clerical capacity did not offend the social niceties of the day (Manners, 1889). Zimmeck identified the broad division of clerical work into 'intellectual' and 'mechanical' tasks. Using the example of the GPO, she related that the employment of women on certain 'mechanical' clerical tasks over time resulted in that class of work being identified as women's work only.

Thus by 1914 there was a distinct gender division in the work structure within the GPO. Zimmeck's model has a major bearing on the official employment of women and clerical labour within the Army Pay Department establishments from 1915 to 1920 (Black, 2008: 197-217). The short experience of the Woolwich women volunteers at the Army Pay Office Woolwich, and the range of the tasks that had to be completed involved both 'mechanical' and 'intellectual' divisions of the clerical structure. For example, women volunteers after seven days' experience of an army pay office were instructing soldiers' wives regarding separation allowance claims, and the interpretation of an ever-changing set of rules for claimants.

Marriage: an inconvenience in the pre-1914 Regular Army

Trustram (2008) has written about marriage and the Victorian Army in her book Women of the Regiment. Her thesis has provided a detailed account of the workings of the restrictive system of the regimental married establishment in the British Army from 1854 to 1914 and the official but abysmal treatment of soldiers' wives who had married 'off the strength'. In 1871 General Sir John Adye considered marriage and the regimental married establishment to be a major inconvenience to the flexibility and efficiency of the Army (TNA WO 33/37; Adye, 1871: 346; Trustram, 2008: 48). Trustram's thesis also describes the consequences of soldiers marrying 'off the strength' before August 1914 and the problems this caused when the wives of soldiers were left behind when regiments embarked for overseas service. Commissioned officers also faced restrictions within the pre 1914 Regular Army. Indeed Beckett commented that,

For officers as for men, there was the same potential conflict, which Trustram identifies between the desire for marriage and what she calls 'male regimental solidarity' [Trustram, 1984: 194-6]. The old military adage applied to officers of course, was that 'subalterns must not marry, captains may marry, majors should marry and colonels must marry' (Beckett, 2000: 468).

According to Trustram, a change in military family allowances only came about when conscription was introduced in 1916 (Trustram, 2008: 85). However, in fact the change occurred before this, when the family separation allowances regulations were radically altered within days after the declaration of war and the suspension of the regimental married establishment. It is argued that the objective of these changes was to boost voluntary enlistment and delay the need for conscription, and reflected the 'short war illusion' (Farrar: 1973), philosophy that prevailed in 1914.

The concept of regimental philanthropy extended into the First World War and perhaps its first manifestation was the women who were voluntarily employed at the Army Pay Office Woolwich from August to November 1914. The recruits volunteering from August 1914, particularly into Kitchener's New Army and the Territorial Force, came from a wider economic and social background than those who had enlisted into the pre-1914 Regular Army. Prior to August 1914 the Regular Army obtained its recruits from the poorest districts of industrial conurbations, mainly located in the north of England: most recruits had previously been casually employed (Strachan, 2006: 208).

The 'ladies' of the regiment and garrison– the origins of the 'Boy-Girls of 1914'

The restrictions of the regimental married establishment restrictions were suspended on 14 August 1914 and this resolved at a stroke the ever-increasing problem faced by the pre-1914 Regular Army and marriage 'off the strength'. Also from 14 August 1914 radical changes were made to the military family allowances system and care for the family of soldiers became the responsibility of government (TNA 123/56, Army Order (AO) 319 19 August 1914). The origins of these reforms are outside the scope of this paper, however suffice to say that the official system of married and family allowances during the course of the Great War was similar to the pre-1914 voluntary aid provided by the Soldiers and Sailors Families Association (SSFA), established in 1885 by Colonel Gildea. There were also other examples of pre-1914 voluntary charities that assisted the families of soldiers including the 'Association for Providing Lodgings for Soldier Wives and Families' that had been formed in 1863 at Aldershot by senior officers and their ladies (Trustram, 2008: 167). The example of SSFA and the Aldershot charity were just a few of the charities within garrisons that cared for soldiers' families.

The ladies of the garrison and regiment played an important role in the social welfare of the Army life prior to August 1914, in both an official and unofficial capacity. Indeed there is some evidence to suggest that a gender/power relationship existed in an otherwise all male dominated British Regular Army. Beckett (2000: pp 463-479) gives examples where officer's wives in the late Victorian Army influenced their husbands' careers and indeed were part of the course their husband' careers. A later example can be seen in 1913, when the Army Council appointed a Committee of Inquiry into the problems of the Army and 'off the strength' marriage, The membership of this Committee included the wives of three senior military officers from Aldershot Command, including Lady Dorothy Haig (HMSO, 1914) (the Tennant Report). The Chair of the Committee, Mrs Tennant, was the wife of the Secretary of State for War The backdrop of women and patronage may explain the origins of the first women volunteers at APO Woolwich who called themselves 'the Boy-Girls of 1914'. It is not recorded whether any of the Boy-Girls of 1914 were or had been members of SSFA or any other regimental charity, however the possibilities suggest that this could have been the case. However, it probable that most of the unofficial women volunteers were spouses of middle ranking army officers.

For example, it was not unusual for the spouses of middle and senior ranking officers to be connected with charitable and social systems within military garrisons and numerous examples of this are reflected in Trustram's thesis. Indeed there a similarities with previous examples of studies of 'the colonial wife, and especially the 'memsahib', that have,

Identified roles performed outside marriage but primarily in terms of activity such as voluntary or social work – an overseas extension pf the so-called 'Lady Bountiful Role' (Beckett, 2000: 464).

Officers' ladies would have been predominantly middle-class, with experience of social and unofficial networking within a military environment in Britain and the Empire. They had considerable experience of maintaining households, being well versed in the domestic duties of running a household that included the organisation of servants and maintaining household accounts and budgets. The social network was reinforced through garrison institutions where their husbands served. This included the church, the officers' mess, garrison sporting and social events (e.g. polo and tennis), and the wider garrison social arena. These voluntary networks, although unofficial, were accepted as being the duties of the ladies of the garrison. This represented a powerful maternal link between the officers of the garrison and the soldiers and their families, whether on the strength or off the strength.

The official changes made in the military family allowances scheme, both in breadth and depth at the beginning of the First World War, caused a major increase in claims. The increase in bureaucracy caused by the increasing manpower strength of the Army and the rise in family allowances for most married men brought about a major logistical problem for the Army Pay Services. From August 1914 to January 1915 the APD establishments were still staffed on a peacetime establishment basis.

The beginnings of a wartime bureaucracy

The official suspension of the regimental married establishment coincided with changes in the scope of entitlement to family allowances. The new regulations meant that all married soldiers, including members of the Territorial Force and Special Reserve as well as those enlisting into Kitchener's New Army were now entitled to family allowances from the day of enlistment as long as the soldier was living and maintaining his family at the time of enlistment.

It was in this chaotic atmosphere that the Woolwich Boy-Girls found themselves in August 1914. Their role within the Woolwich Army Pay Office extended beyond that of mere envelope stuffers. Within days of their arrival, along with the regular APD / APC staff, they had to interpret the ever-changing regulations that were promulgated in the weekly and sometimes daily Army Orders and Paymaster-in-chief directives, and the ever-increasing amendments to the Allowances Regulations Manual. Despite pressures faced by all APOs in the United Kingdom to initiate active service documentation regarding the mobilisation of reservists, the embodiment of the Territorial Force, and the introduction of the New Armies, a directive issued by the War Office Finance Branch insisted that the administration of separation allowances was the major priority. This was achieved through media and public pressure being placed on the Secretary of State for War. Therefore, within days of volunteering 'the APC Girls' found themselves dealing either personally or through the post with the wives of soldiers, giving them advice regarding family and separation allowance claims.

Image: August 1914: Enter Mrs. 'Ordnance Officer' – the first lady volunteer?

Although the article 'Boy-Girls of 1914' does not name any of the women volunteers, it does suggest that the first woman 'volunteer' was the wife of the Commanding Officer of the Ordnance Depot adjacent to APO Woolwich. KFK, the anonymous author of the 'Boy-Girls of 1914', recalled the arrival of 'Mrs Ordnance Officer' being due to the enormous pressure experienced by the officer in charge of the separation allowance wing at the Army Pay Office Woolwich and occurred when:

The officer in charge of separation [Oi/c] allowances met the officer in charge of the Ordnance Department on the stone stairs of the barracks on one of those glorious August days. There was that in the demur of the Oi/c Separation (who had not rested for many days and nights), which constrained the Oi/c Ordnance to offer his wife's services as an addresser of envelopes. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

However, Mrs Ordnance Officer then brought a few of her friends along to assist with the increasing bureaucracy that was stretching the human resources at APO Woolwich to the limit:

And so it came about that Mrs. Ordnance Officer and a few girlfriends placidly addressed envelopes in the garden of the Barracks (the Barracks themselves being full to overflowing) whiles the state of the Office itself grew momently more desperate with every recruit who swelled the British Expeditionary Force. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

Despite the slowness of government to consider women clerical workers being employed in government offices, this did not prevent the Regimental Paymaster of APO Woolwich and the officer in charge of the separation allowance wing from allowing the recruitment of women volunteers and these women were perhaps the example of the 'Lady Bountiful role' as identified by Beckett, (2000: 464). Unlike Beckett however, who was referring to Lady Bountiful overseas the example of the first unofficial women who volunteered for work at APO Woolwich reflected the Lady Bountiful within a home garrison.

Colonel AB Church, the Regimental Paymaster commanding APO Woolwich was determined to resolve the staffing problem, and he was gladly prepared to accept th4 services of women volunteers albeit in an unofficial capacity. According to KFK, he decided that

"if the War Office wouldn't send him men he would put his faith in women, and have – (Oh! Extraordinary and unheard of notion) girl clerks in his branch of the Office. But where to put them?" (The Souvenir, 1920: 5).

Mrs Ordnance Officer began working in the garden of Woolwich Dockyard one week after the declaration of war. Within a few days she had recruited a number of her friends and within 14 days the number of women volunteers had risen to thirty. Those with 6 days' experience or more became supervisor to the new volunteers. KFK observed,

"in less than no time from the birth of the idea there were some 30 of us collected round a huge table, the [first] volunteers from the garden with their whole six days experience for supervisors" (The Souvenir, 1920: 5).

Within days there were office accommodation problems within Woolwich Garrison that included a lack of office space for APO Woolwich. The compulsory eviction of soldiers' wives and their children was previously mentioned, and initially the overspill from APO Woolwich was temporarily resolved through the use of vacant married quarters, but this source soon dried up. Therefore, using his initiative, the CO of the Separation Allowance Wing

Went forth on his bicycle and obtained the favour of two big rooms in the Local Labour Exchange ... and not a pen or an inkpot in the place! 'Why on earth haven't you brought your pens?' cried the CO. to the round-eyed crew who regarded him, and before they could find voice – 'Well cut along and get some'. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

Indeed, the decision of the captain in charge of the separation allowance wing to secure this accommodation was a wise tactical decision because, twice a day, the ever-increasing mountain of correspondence for mailing could be quickly taken across the road to the GPO sorting and parcels office, adjacent to Woolwich Arsenal railway station; the erstwhile captain taking a leading role and setting an example. The volunteers who were working in the upper rooms at the Labour Exchange witnessed the twice-daily ritual as

"the men stood ready with sacks to snatch the completed bundles from the girls hands and take them in carts to the GPO, the CO in shirt sleeves giving the lead at carrying the sacks down the stairs and into the road" (The Souvenir, 1920: 5).

The increase in technical and general administrative finance duties

For the first six days the first few volunteers, including 'Mrs Ordnance Officer', had worked in the garden of Woolwich Dockyard sealing and addressing envelopes. As previously mentioned by KFK, within six days the number of volunteers had reached thirty and they were now located in the upper rooms of Woolwich Labour Exchange. Other women volunteers were employed in the preparation of active service pay and mess books (AB 64) (contemporaneously called draft books) in respect of Army Reservists. The army pay books had covers made of a thick textile material that was dyed dark red, and by the end of each day the hands of the volunteers were stained by red dye. KFK observed that:

The work came in from the Barracks –Draft books! (We called them coupons in those days) and the red dye came off on our hands, as we sorted, and filled in, and stamped and packed the live day long. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

Other more technical duties given to the lady volunteers included the audit and preparation of army pay accounts and expenses claims; the documentation, administration and despatch of money orders related to compulsory and voluntary allocations from a soldier's wages also had to be administered. The necessary documentation in order for a soldier's wife to draw separation allowances from the GPO was similar in format to a chequebook and was called a draft. Each book contained 13 drafts on a quarterly basis of 13 weeks each. This task was particularly labour-intensive and each of the 13 drafts was filled out individually with the same information. The completed drafts were then sent to the appropriate paying post office that kept the draft book. The wife of a soldier nominated the appropriate post office within the UK where she collected her weekly entitlement on production of an identity card, also prepared by the respective APO. This system continued throughout the period of the Great War. It was assumed at this time that there would be less chance of fraud if the nominated post office retained the draft book.

The peacetime administration of separation allowances was made monthly and in advance to the entitled dependant of a soldier who was on the regimental married establishment but unaccompanied. However, by the second week of the war the frequency of payment was reduced to weekly. The Army Pay Services did not anticipate the change from monthly to weekly payments; however these changes were made due to public pressure placed on the Secretary of State for War. One former paymaster commented some twenty years after the event that it was:

A change ... which we were consequently not ready, but it was demanded by the public, and the War Office had to submit. The [weekly] process was, if anything, much slower as thirteen weekly drafts, which required much the same written particulars on each as on a money order, had to be made out before the whole could be dispatched to the appropriate post office. (RAPC Journal, 1935 Part 1, p.131)

However there was also the problem of locating displaced wives of soldiers who were required to complete the separation allowance application. One former regimental paymaster commented

"Regimental Paymasters ... sent their clerks to married quarters and lodgings to collect the necessary information to enable them to pay" (RAPC Journal, 1935-6, Part 1, p132).

What is not recorded in The Souvenir is that within Woolwich Garrison a number of the spouses and families of soldiers had been evicted from their married quarters and were now living in temporary accommodation, possibly within the Greenwich, Plumstead and Woolwich areas (The Woolwich Pioneer, August 1914). They may have relocated a number of times within two or three weeks, determined by the length of tenancy and the exorbitant rent charged by profiteering landlords. Locating the displaced wives must have been a major task for the APO clerks and possibly the women volunteers too.

The women volunteers were also required to answer correspondence from the dependants of soldiers, or to deal with them personally. Such queries possibly involved the wives of soldiers in filling out a claims form as mentioned above, or dealing with a complaint, the most common being that a claim although submitted had not been received by the post office. There would have been cases of both soldiers and their spouses who were either semi-illiterate or illiterate. Thus the women volunteers and the regular military staff at APO Woolwich may have had to complete the necessary documentation for the spouse in order for her to claim her due allowances. An example of a letter received at the Separation Allowance Wing of APO Woolwich was recorded by KFK as follows:

Dear Sir

I have received no pay since my husband has gone away from nowhere.

(The Souvenir, 1920: 6)

There were other difficulties faced by all army pay offices throughout the Great War. For example, apart from the literacy difficulties as already mentioned, the wife of a soldier may not have known her husband's exact location and regimental number. In many instances during the Great War, soldiers were transferred between units and transit depots before disembarking for France and other operational theatres of war. Until 1920 the regimental number of a soldier changed if he was transferred to another unit, for example a driver of the RFA being compulsory transferred to the RHA.

The initiation of the women volunteers into the realms of an army pay office struggling to cope with an unprecedented increase in bureaucracy and interpreting new official regulations was made clear by KFK, who remembered that:

There are still a few in the Office who will remember and corroborate. The entry of the APC girls on the scene of action, properly set forth, would go far to remove the idea that a government office is a monotonous conventional place ... The volunteers answered letters in the most blissful ignorance as to what they were writing about, from half frantic women who hardly knew what they were writing about either. Granted again that half of us at the time were voluntary workers with an abysmal ignorance of business ways and a pleasant insouciance as to business hours - who thought 'Bdr' stood for Brigadier [the actual definition was bombardier, a rank equating to corporal in the RFA and RHA], and 'Dr' for Doctor [the actual definition could have meant debit or Driver an equivalent rank in the ASC, RFA and RHA to that of private]. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

An examination of Army Orders between August and October for 1914 revealed 12 major amendments to the allowance regulations (TNA WO 123/56). Just prior to the demise of the Woolwich 'Boy-Girls' towards the end of October 1914, the separation allowances and compulsory deductions for a soldier's maintenance of his family increased, as did the weekly normal pay of soldiers. The amended allowance regulations extended categories of a dependant who was not eligible before 5 August 1914. The extended categories included the soldier's grandparents, parents, step-parents, brothers and sisters including half-brothers and half-sisters who prior to enlistment had been dependent on the soldier's previous civilian salary. A radical change during this period was the acceptance by the War Office of common law (cohabiting) relationships for the purposes of separation allowance entitlement. The Regulations now included that

"a woman who had been entirely dependent on a soldier for her maintenance and who would otherwise be destitute, and the children of the soldier in charge of such person." (TNA WO 123/56: Army Order 440, 27 October 1914)

Other problems included the low stock of application forms for separation and other allowances. The original stock required for a peacetime establishment was not high due to the low marriage rate. The holding stocks soon ran out and there were delays in printing a new stock. Printing companies were hard pushed, as they were also busy with other Army contracts for military forms and manuals for infantry training for an army now placed on a war footing. The printing of separation allowance forms was not deemed to be a priority despite the War Office directive prioritising the issue of separation allowances (RAPC Journal, 1935, part 1, p132).

The women volunteers learnt the task of administering the 'black art' of army pay administration and accounts very quickly despite a steep learning curve, ever-changing regulations, and an acute shortage of the necessary official documents and forms.

'There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy'

IMAGE: Shakespeare 'Hamlet'

No Halo in this War: Morale and Facing a Traditional all Male Macho Military Environment.

The first Woolwich women volunteers who were the 1914 Girls may have already been used to a military culture given that perhaps, most were drawn from spouses and other dependents from the Garrison community. Also during the early days of August and September 1914 morale and a sense of melancholy nationwide were high and this was also reflected with the women volunteers at APO Woolwich, a point noted by KFK who commented thus,

What a staff! Never the same two days running! Miss Brown couldn't come this morning. Her boy goes today, and she simply had to see him off. And the CO would agree, 'oh the poor girl of course she had'. Or he would forcibly forbid some blunderer ever to enter his presence or the Labour Exchange again, and she would vanish in tears and be seen no more- for perhaps a day and a half- when she would be rediscovered, demure and unobtrusive, in her old seat.

We nearly always worked till nine at night, and at top stretch every minute of the time. We worked because we were excited, and the world was upside down, and our bys were going away, and our hearts were aching, and because the bands with their dreadful cheerfulness playing drafts away all day long at the station across the road. And we worked because of the CO ... (The Souvenir, 1920: 6).

In her article, KFK only mentions one name, a Miss Brown who was allowed to see her boy friend off to war by the CO. Whether, or not Miss Brown was one of the Girls at APO Woolwich in August October 1914 is conjecture.

As the War progressed and the recruitment of women as temporary civil servants became official policy, the women staff no doubt had to cope with an alien culture of a military environment. The official although unpublished, history of the administration of separation allowances recorded that,

It is true women joined with unbounded enthusiasm for war work, and left in a few days when they recognised that there was real grinding work to be done without any halo, or when they, or we, found they were quite unsuited temperamentally and educationally for what they had undertaken ... but that was expected and in no way disheartened the directing staff who grappled with renewed vigour (TNA WO32/9316, History of Separation Allowances).

Nothing is suggested about the reason why some women may have been discharged. However, Captain A Broughton APD, a member of the directing staff and possibly a hirer and firer of women clerical labour qualified the statement made by the official history as quoted above by admitting that,

The faces of those I have sacked are ever before me (The Souvenir, 1920: 11).

There is also the culture of the military environment with its different mores and protocols which could seem rather irritating to one not used to it, a point made by Colonel Blackmore APD who later commanded the Woolwich No 2 APO at Blackheath. He stated that,

Work was carried on by both sexes under semi-military discipline [where] the discipline though slightly irksome at times was new and possibly amusing to some (The Souvenir, 1920. 12).

The Souvenir contains a page of cartoons depicting scenes of APO Woolwich, with quotes from Shakespeare to enhance the humour. The cartoon below depicts a women member of staff at APO Woolwich, allegedly arriving late for work, or duty according to the military culture, and being mildly rebuked by a senior non commissioned officer. She denies it, with the quote from Shakespeare's poems, 'Some there are top of their persuasive tongue carry all argument'

IMAGE: Cartoon

It is quite possible that the women volunteers and later the official women clerks and superintendents did suffer from elements of sex discrimination and the pressures of a macho military culture. The Souvenir contains impressions written by the pay staff related to their experience working at APO Woolwich during the Great War. For example, one civilian acting paymaster, (AP), WW Burton, appeared to have written a derogatory comment about lady superintendents and women clerks employed at APO Woolwich by suggesting that,

'Generally speaking, the ladies generally speaking'. (The Souvenir, 1920: 12).

The most poignant impression to suggest that there was discrimination and perhaps bullying at APO Woolwich after 1914 was written by AE Moat a Lady Superintendent who was the only contributor to the farewell page of the Souvenir. She made perhaps a heart felt statement as follows.

'Farewell little black face, weird and deformed. Badly abused and by all APs. We have linked some funny things together that only time and change can sever.' (The Souvenir, 1920: 12).

The impression made by AE Moat was the only one that was printed on the 'Impressions of the Pay Staff' page! Despite a detailed investigation nothing has been found about AE Moat.

One area discovered that may represent discrimination related to the Regimental Pay Office, Dublin located at the Linen Hall Barracks. This was completely destroyed during the Easter rising. Recently discovered Army Council Instructions (ACIs) No. 1901 issued in 1916 found at the Adjutant General Corps Museum in Winchester shows male civilian staff were paid a bonus and received extra pay for their efforts in re-establishing RPO Dublin in a different location and in replicating pay documentation destroyed in the rising. There was no mention of such monetary increases in pay or bonuses for women staff. Whether this was blatant sexual discrimination due to their temporary status, or that they had been instructed to stay at home until the reorganization was complete is not known. However there is also no mention of similar monetary rewards, or any other type of rewards being awarded to the uniformed APC staff.

Why 'The Boy Girls of 1914'?

The question arises who were the Boy Girls of 1914, and why did KFK not call her short article 'The Girls of 1914'? The answer is to be found in the text of KFK's article. In her brief history of the Boy Girls of 1914, KFK suggests that the regimental paymaster at APO Woolwich paid the women volunteers by changing their 'girl' names into 'boy' names on the respective paylist in order to mask the true identity of the women working at APO Woolwich. This, according to KFK, was the origins of the name 'The Boy Girls of 1914'. This scheme worked for a short while. The rate of pay afforded to the Boy-Girls was the same as that for a male civilian clerk (civil service) at 18 shillings a week. There is a hint of alleged 'fraud' here as the respective pay sheets with the ladies' names on them would never get past the War Office auditors. 'KFK', writing in 1920, commented that:

Granted we masqueraded modestly on paper as "Boys" for the eyes of the War Office when it came to our pay sheets. ...But the fact remains that there were girls doing Army Pay work, under an Army Pay officer, and getting Army pay for it-eighteen shillings a week and no overtime pay and proud of it too. (The Souvenir, 1920: 5)

One year later after the recruitment of women as temporary clerks within UK-based army pay offices had been officially approved, women clerks were paid 12 shillings a week for the same duties as their male counterparts. It would therefore appear that Colonel Church, in attempting to disguise the 'girls' as 'boys' for the benefit of payment had actually and perhaps inadvertently introduced equal pay into APO Woolwich in the late summer of 1914!

The War Office Finance Branch eventually discovered that women volunteers were being unofficially employed at APO Woolwich, and also receiving unauthorised pay. Despite the acute staffing problems at all APD establishments the Director of Finance at the War Office (a higher civil servant) and the Paymaster-in-Chief, (a colonel in the APD), were unmoved and ordered the removal of the volunteers. KFK noted that:

The War Office woke to the fact that the 'boys' were really girls and waking, disapproved, and the order came through for our disbanding. And then we began to realise how we loved it all. (The Souvenir, 1920: 6)

However, the Boy-Girls were not going without a fight, and drew up a petition for presentation to the War Office. The British military then (and now) were not accustomed to such practices and, according to KFK, all the women signed the petition, but

"most were too busy to read it, but we all signed with fervour, the purport of the document (save the mark) being that we wanted to go on working on any terms whatever!" (The Souvenir, 1920: 6).

However, after the event KFK recounts that:

Mercifully the CO [Colonel Church] intercepted it as it was being handed round for a few remaining signatures, and on the devoted head of the girl found holding it fell the full measure of his horror. It was a stormy scene while it lasted, but the clerk who was least afraid was deputed to apologise on behalf of us all, and the net result was a strengthening, if possible, of mutual esteem all round. (The Souvenir, 1920: 6)

By the end of October 1914 the 'Boy Girls' unofficial sojourn as women clerks within an army pay office came to an end. KFK remarked:

"So the War Office decree was unopposed, as is the way of such, and in October 1914, after an eventful ten weeks, the 'Boy-Girls' were discharged" (The Souvenir, 1920: 6).

KFK also commented that the 'Boy-Girls' never "guessed that in less than six months they were to take and hold the stage again in triumph, but this time in answer to the S.O.S. from the War Office for girl clerks" (The Souvenir, 1920: 6). What is perhaps surprising is that it took the War Office and other government departments some considerable time to consider the employment more widely of women in government offices, despite calls from the NUSS for women to be recruited into government office, a point noted earlier in this paper.

The first women clerks were officially recruited in November 1914 for duties in Accounts 2 at the War Office Finance Branch (TNA WO 32/9316, The History of Separation Allowances and Effects). This was a few days after the Woolwich volunteers had been removed. The first women clerks to be officially recruited for employment within the UK-based army and command pay offices commenced in January 1915 and continued until the end of 1919. In January 1916 women supervisors, contemporarily called lady superintendents, were recruited specifically to manage the technical and welfare aspects within respective APD establishments. Lady Superintendents had the same status as a lieutenant or captain (Assistant Paymaster) APD.

Who were the 'Boy-Girls' of 1914?

It is difficult to ascertain the actual identity of KFK or any of the women volunteers with absolute certainty. It is doubtful that KFK was 'Mrs Ordnance Officer', however it is possible with some accuracy to identify whom 'Mrs Ordnance Officer' was. A scrutiny of the Army Lists for 1914 (January and July) can pinpoint possible candidates. The senior officer commanding the Army Ordnance Depot at Woolwich Dockyard in July 1914 was Colonel (Temporary Brigadier-General) George James Butcher, CMG, CB. Colonel Butcher finished his Army career in 1922 as a major general. He had been knighted in 1918 (KCMG) for his services as Deputy Director of Ordnance Services (DDOS) at Woolwich Arsenal. Major General Butcher had married Lydia Simpson of Old Park, Clapham in 1896: Lydia died in 1937, two years before her husband. However, the funeral notice of Lady Lydia Butcher does not mention her activities during the Great War (The Hampshire Telegraph, 27 October 1937). It is therefore quite possible that 'Mrs Ordnance Officer', who sat in the garden of Woolwich Dockyard during the glorious high summer of early August 1914 addressing envelopes, was Mrs. Lydia Butcher.

There is little doubt that these women were linked to a garrison network, as it did not take long for 'Mrs Ordnance Officer' to rally her friends and acquaintances for support. If they were the wives of officers of Woolwich Garrison no doubt most was have previously been in a 'Lady Bountiful' role in previous overseas posting.

The legacy of the women volunteers at APO Woolwich and the success of the separation allowance scheme

It is not known whether the experience of the Boy-Girls of 1914 was unique or whether other Army Pay Offices in the UK also had their women volunteers from August 1914. No record has yet been discovered to prove this. As The Souvenir is the only document relating to the 1914 experience, one is inclined to assume that the experience of women volunteers was unique.

The Army Pay Services of 1914, and indeed throughout the period of the Great War, struggled through the ever-increasing bureaucracy resulting from rising military strength and the continual amendments made to existing allowances regulations for the Army. For example the Allowance Regulations manual was written three times between 1915 and 1917 (TNA WO 32/9316). The area of pay and allowances was never a major problem to the British Army during the First World War. There was never any major parliamentary debate about alleged inefficiencies of the Army Pay Services. Pedersen (1990) has contributed to the social economics of allowances paid to soldiers' dependants both in the UK and France during World War One. In particular she emphasised the neglect in taking into account the dependants' needs rather than the soldiers' needs (Pedersen, 1990, 984-1008: 1995, Chapter 2, 79-130). Pedersen is correct in her analysis, but it must be remembered, and as outlined in this paper, that the system after August 1914 was far superior in scope over the pre 1914 period when the marital status of soldiers was governed through the inflexible regimental married establishment regulations as demonstrated by Trustram, (2008).

The reason for the rapid change in scope and depth of separation allowances was due in part to the recruitment needs. During the first two months of the Great War, there was growing optimism that the war would be over by Christmas, despite the predictions of both Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, and David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. What frightened Asquith and the Liberal Government was the thought of the introduction of conscription in 1914; later in 1916 the introduction of conscription was a major factor in the Liberal split. However, it is possible that conscription was delayed for two years, from 1914 to 1916, as the strength of the Army grew in size through voluntary enlistment. In addition, the widening of the scope of separation and other allowances during the first few weeks of the Great War undoubtedly enhanced morale within the Army and encouraged voluntary recruiting.

The legacy of the women volunteers who called themselves the 'Boy Girls of 1914' became apparent as the First World War progressed. For example, at the time of the Armistice the number of APOs in the UK had increased from 27 to 44. The Army Pay Office Woolwich, shortly after the demise of the women volunteers of 1914, was divided into two separate entities: the accounts of the RHA and RFA were relocated to nearby Blackheath which was known as Number 1 Office APO Woolwich, whilst the ASC personal accounts remained at Woolwich and became Number 2 Office, APO Woolwich. However its location became scattered within Woolwich and the neighbouring Plumstead areas. Office accommodation was requisitioned from schools, libraries and even a local Masonic Hall (Army Order 243 July 1915). In January 1916 a hutted camp was built on Woolwich Common to allow for more Army Pay Office accommodation.

The overall numbers of staff at the Woolwich Army Pay Office increased from 90 in August 1914 to 6,000 in November 1918, about two thirds were women employed as temporary civil servants. The number of women employed by the Army Pay Services in Britain throughout the course of the war peaked at 28,000, comprising of women clerks and lady superintendents employed as temporary civil servants (Black, 2006, 195-218; 2008: 211; HMSO Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, Section 23, Growth of the Royal Army Pay Department and Corps, March 1922, reprinted in 1999).

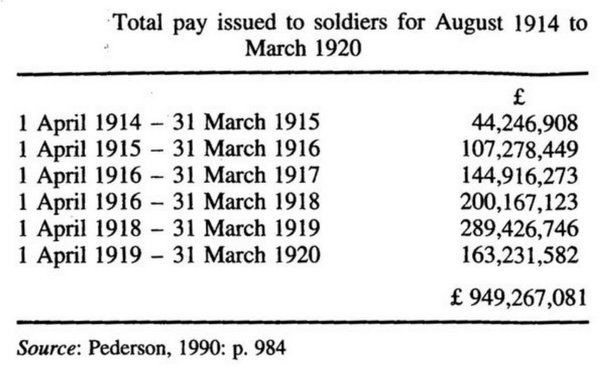

In order to appreciate the role played by women employed in Army Pay department establishments during the First World War the following brief statistics will hopefully illuminate the increasing bureaucracy that followed with ever expanding army from the raising of the Kitchener's Army in 1914-15 and the conscripted army from 1916. The first chart demonstrates the total pay issued to ordinary private soldiers (excluding NCOs warrant officers and officers) from August 1914 to March 1920.

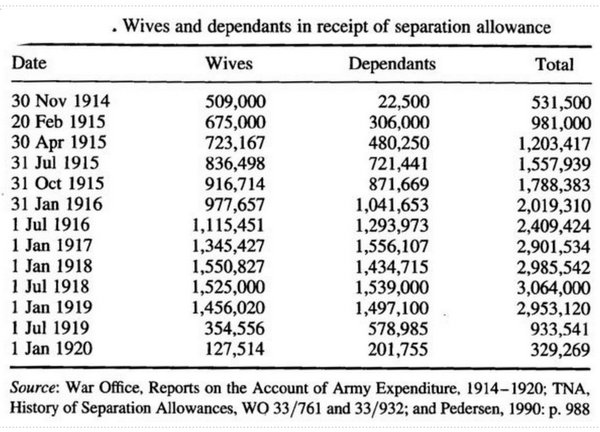

The second chart demonstrates the number of wives and dependents in receipt of separation allowance from 30 November 1914 to 1 January 1920

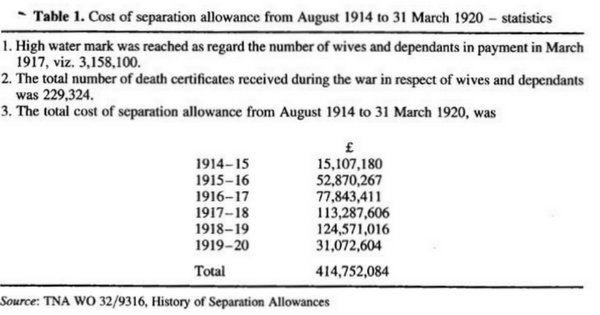

The third chart reveals the cost of separation allowance from August 1914 to 31 March 1920

Conclusion

If the 1914 women volunteers of APO Woolwich were pioneers, so too was Colonel AB Church, the Regimental Paymaster commanding APO Woolwich, and the anonymous captain commanding the separation allowance wing. They allowed women into what was an all-male bastion without the permission of a War Office that was reluctant to recruit women clerical staff. It has not been substantiated whether the experience of the 'Boy-Girls of 1914' influenced the War Office Finance Branch to recruit women clerical staff for duties with APD establishments in the United Kingdom. However by January 1915 women were being recruited as temporary civil servants into APD establishments in Britain and Ireland either a clerks or as lady superintendents and the experience of the first women volunteers at Woolwich in August 1914 may have been the deciding factor for the War Office to make a decision to recruit women.

The Boy Girls of 1914 extended the scope of gender integration within military establishments that eventually became a feature, albeit a temporary one, during both the First and Second World Wars. However it was not until the last decade of the 20th century that the armed services of Britain became fully and permanently gender-integrated. KFK and the Boy Girls of 1914 would have no doubt approved.

The final cartoon from the pages of the Souvenir depicts the same woman who entered APO Woolwich as also being the last woman leaving Office in 1920, with the directing staff not too happy about her leaving. In contrast the directing staff in 1914 were not that happy about women entering their establishment. Whether the cartoon displays genuine sorrow at her leaving, or it was just the cartoonist's whim is conjecture.

Image: 1920: The Women Leave until 1940

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- The Archives of the Adjutant General's Corps, Winchester

- The Army Pay Corps News no.5, May 1916.

- The Royal Army Pay Corps Journal, 1933 and 1935.

- King's Regulations for the Army 1913.

- Manual of Military Law, 1914

- The British Newspaper Archives, Colindale, London

- The Hampshire Telegraph, 27 October 1937

- The Nineteenth Century, August 1871 article by General Sir John Adye, The British Army, p346.

- The Spectator 12 September 1914.

- The Times Newspaper 24 February 1857

- The Times Newspaper, 27 November 1939

- The Woolwich Pioneer 18 August 1914

- The National Archives, Kew

- The Army List, 1913 and 1914.

- WO 123/56 Army Orders, 1914

- WO 33/37, Married Establishments in the Army 1881.

- WO 32/9316 History of Separation Allowances and Effects during the Great War.

- HMSO Report of An Enquiry by Mrs Tennant Regarding the Conditions of Marriage off the strength, 1914 (Cd 7441), li.

- HMSO Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, Section 23, Growth of the Royal Army Pay Department and Corps, March 1922, reprinted in 1999.

Secondary Sources

- Baynes J (1987). Morale; A Study of Men and Courage (new edition). London: Leo Cooper.

- Beckett Ian FW (2000), Women and Patronage in the Late Victorian Army. History Vol. 85, July 2000, pp 463-79.

- Black J (2008). Women clerical staff employed in the UK-based Army Pay Department establishments. In: (eds) Anne Laurence, Josephine Maltby and Josephine Maltby 'Women and their Money 1700-1950: Essays on women and finance'. London: Routledge ch 14 pp. 197-217)

- Black J (2006). War Women and Accounting: Female Staff in the UK Army Pay Department Offices, 1914-1920, Accounting, Business & Finance History, vol.16, no.2, pp195-218.

- Braybon G (1981). Women Workers in the First World War. London: Routledge.

- Braybon G (1987). Out of the Cage. London: Rivers Oram Press

- Campbell-Kelly M (1992) Large-scale data processing in the Prudential 1850-1930, Accounting Business and Financial History, 2, 1992, pp117-39.

- Campbell-Kelly M (1998) Data processing and technological change: the Post Office Savings Bank, 1861-1930, Technology and Culture, 39, 1998, pp1-32.

- Churchill S (Lieutenant Colonel APD) (1895). Forbidden Fruit for Young Men. London: James Nisbett & Co.

- French D (2005). Military Identities: The Regimental System and the British People 1870-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hinchliffe L G (1983) 'Trust and be Trusted': The Royal Army Pay Corps and its Origins. Published privately by the Corps Headquarters RAPC, Worthy Down, Winchester, Hants.

- Imperial War Museum (Reference K 87/465): The Souvenir.

- Pederson S (1995) Dependence and the origins of the Welfare State: Britain and France 1914-45, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Skelley A R (1977). The Victorian Army at Home. Montreal: Queen's University Press.

- Strachan H (2000). The Politics of the British Army. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Thom D (2000). Nice Girls and Rude Girls: women workers in World War 1. London: Tauris.

- Trustram M (2008 reprinted). Women of the Regiment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Walker S P (1998). How to secure your husband's esteem: accounting and private patriarchy in the British middle-class household during the nineteenth century. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23 (5/6): 485-514.

- Winter J and Prost A (2005). The Great War in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zimmeck M (1986). Jobs for the girls: the expansion of clerical work for women, 1850-1914. In: John A V (ed) Unequal opportunities: Women's Employment in England 1800-1918, pp145-172. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appendix A

Photograph taken outside Cambridge Barracks, Woolwich in 1917 showing women clerks working at the Army Pay Office, part of which was situated in the Barracks, along with soldiers of the Army Service Corps. These could have been soldier clerks as Cambridge Barracks also was at this time, the location of the Army Service Corps Record Office.

Appendix B

Recruiting Poster 1914 for the Public Schools Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). The inducement is Regular Army rates of pay including separation allowances. Separation allowances were not on entitlement n enlistment before 4 August 1914 nor after 1918.

Article by Dr John Black

John Black will be giving a presentation at the Midlands (East) branch of the Western Front Association on 14 April 2017. Find out more about his talk here: 'Nellie Hurcomb and the Army Pay Office, Nottingham'