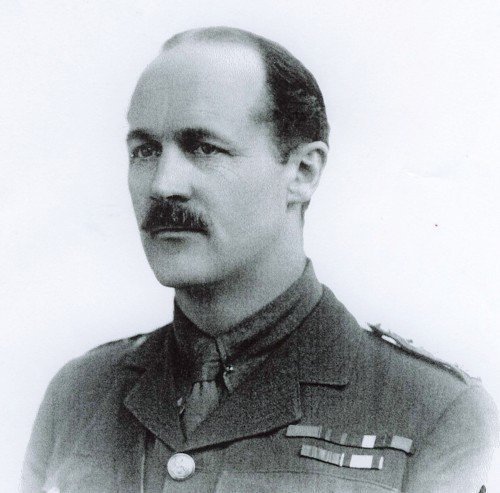

Ivor Thord-Gray - Mercenary, Spy? Thief? … and CO 11th Northumberland Fusiliers

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Ivor Thord-Gray - Mercenary, Spy? Thief? … and CO 11th Northumberland Fusiliers

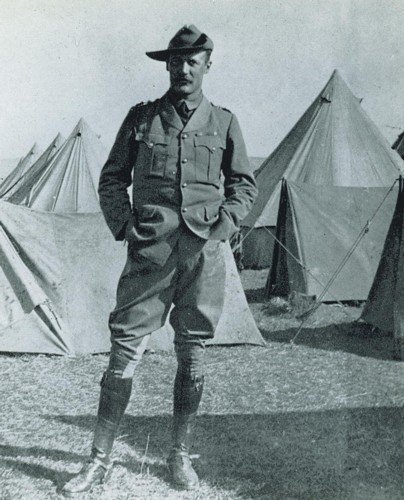

Ivor Thord-Gray was a man for whom war (to paraphrase Lord Reith) was ‘in his bones’. A Swede, born Ivar Thord Hallström (the change in name being for reasons unknown) in Stockholm on 17 April 1878, he set out on a life that would have made good fiction if it were not actually true. After two years on merchant ships (1893-5), he landed in Cape Town.

1) Note on pictures.

South Africa

Thord-Gray’s ten or so years in South Africa encompassed five conflicts, fighting first and last under the British flag, this bracketing a spell with German forces. He may first have tried his hand at farming, but then became a prison guard on Robben Island, where he developed his life-long interest in fencing – he would also become a world champion archer. His officer’s file at the National Archives records him first as having joined the Cape Mounted Rifles as a private in 1897 in the Bechuanaland Campaign (conducted against a series of revolts in response to government efforts to control a very bad rinderpest outbreak) and the Lefleur Rebellion where the outbreak was manipulated to mobilize the Griquas, and probably also in rinderpest-infected Pondoland, all in 1897. (2)He then took part in the Boer War (1899-1902), the Mounted Rifles serving in many areas. He wrote that he ‘passed Cavalry, Mounted Infantry and Maxim Instructor, Field and Horse Artillery’. He subsequently joined the South African Constabulary in 1902-3 (‘Mounted Infantry and Maxim Instructor’). In that year he described himself as working for the Transvaal Civil Service, but also claimed that he raised a squadron of the Northern Rifles in 1904.

His officer’s file lists him as fighting ‘with British forces’ in Damaraland in 1905. The report compiler’s history and geography had suffered a momentary aberration, as this conflict, of course, took place in German South West Africa, the native rebellion there having ramped up in 1904. He in fact served with German Schutztruppe, which consisted of volunteer European commissioned and non-commissioned officers. Thord-Gray was thus, at the very least, a witness to (and possible participant in) the Herero and Namaqua genocide (estimated at 80,000 deaths), the first such of the 20th century.

In 1906 he became a Captain in the British East Africa Police, an employment disrupted by his last military venture in South Africa, with Royston’s Horse. This unit was involved in the Bambatha (Zulu) Rebellion of 1906, being raised (Thord-Gray claiming to have raised the unit with Royston himself) within a week and a half for specific involvement.

He was present at the final showdown at the Mome Gorge, where 3-4,000 Zulus were killed, a campaign which Gandhi later described as ‘no war but a man hunt’. The slaughter at the Gorge was indeed a confrontation mainly between assegai and Maxim. He was mentioned in despatches and promoted Captain on 24 July 1906, ‘Commanding Squadron and Battery Maxims’.

The second verse of ‘Bambatas Awakening in the Morning’ runs:

‘Do you ken Royston’s Horse at the break of day,

Royston and Frazer, Midley and Gray,

From hill-top to valley, thirsting for fray,

As they led Royston´s Horse in the morning.’

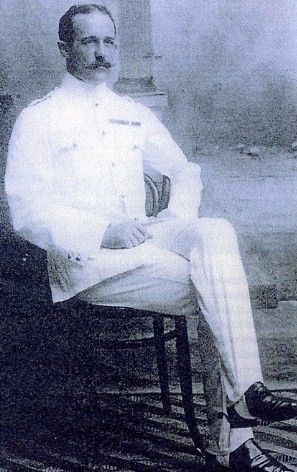

The Philippines, Vietnam, Libya and China

Allegedly, no doubt on the back of his German connection, Thord-Gray travelled to Germany to join up in potential fighting in the First Moroccan Crisis, but was not accepted. Later in 1906 he was on the other side of the world, serving as Captain with the Philippine Constabulary (the ‘US Foreign Legion’). The Philippine-American War had ended in 1902, and the Constabulary was established to deal with the remnants of the insurgents, notably the Moro Rebellion, when the Constabulary was engaged in Leyte and Samar.

Thord-Gray then spent a more peaceful time as a manager for a rubber company in Sumatra, but his irresistible itch for conflict caused him to resign and took him to join the French Foreign Legion in the Tonkin Protectorate (northern Vietnam) in 1909, just one year of Hoang Hoa Tham’s lengthy rebellion. He returned to the rubber plantations, joining the Sungei Liang Rubber Company in Malaya as a manager in July 1910, but resigned again in October 1911 and now went to join the Italians in the Italo-Turkish war of 1911, ousting the Ottomans from Tripoli. A precursor to the First World War, this sparked nationalism in the Balkan states who had seen how easily the Turks had been trounced. Thord-Gray then turned to Asia, apparently engaged in the latter stages of the 1911 Revolution in China which overthrew the Qing Dynasty and saw Sun Yat-sen installed as the first president of the Republic. His engagements in both places must have been brief, as he returned to the rubber trees in June 1912 (Glenealy Estate, Kuala Lumpur), finally quitting in October 1913.

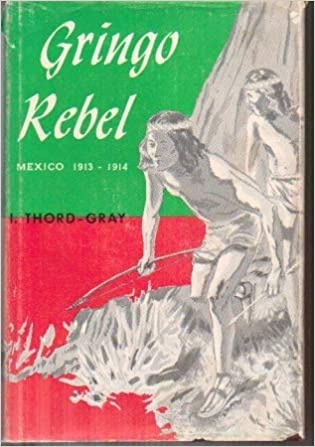

Mexico

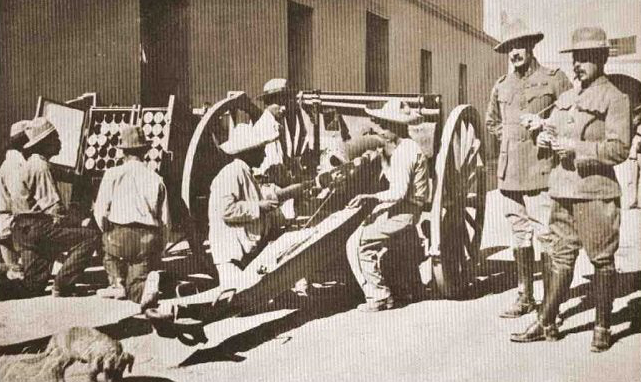

In 1913-14 he fought in the Mexican Revolution, obtaining senior command for the first time. His exploits are (no doubt self-servingly) described by himself in ‘Gringo Rebel’. Thord-Gray tells us that, bored with the slow pace of the Chinese revolution, he was one day drinking gin in the German Club in Shanghai together with an American agent, a German and a Venezuelan exile and fell into conversation about the revolutionary movement there – ‘I decided to go take a look’. (3) This claim, of course, must be placed in the light of the evidence of the GOC Straits Settlements, who researched and provided details of his three spells on rubber plantations. His decision to ‘take a look’ was hardly acted upon swiftly. However, armed with a permit for Mexico as an archaeologist and anthropologist he arrived at the end of 1913.

He allegedly became an artillery officer for ‘Pancho’ Villa by mending broken cannon, progressing to arms smuggling from the United States. The ease with which all this was achieved has led some to presume Thord-Gray was an American agent, the Americans backed the rebels in the overthrow of the Huerta regime, which had previously overthrown (and murdered) the democratically elected President Madero. He described himself as ‘Commandant of the Horse and Field Artillery’.

Villa’s star no longer being in the ascendant with the Americans, they (and Thord-Gray), switched to the Carranza movement, where he initially was instructor for cavalry and artillery. He describes himself as becoming ‘Chief of Staff to the First Army Corps’, to General Lucio Blanco, as well as ‘Colonel and Brigadier commanding Cavalry Brigade still holding position as Chief of Staff’’, and as having ‘directed the movements of the whole Army Corps when I resigned’. In a foreword to an edition of ‘Gringo Rebel’ Jorge Aguilar Mora, Professor of Latin American Literature in the USA uses the words ‘mythomaniac, naive, ambitious, liar, and even traitor to Mexico’ variously to describe our ‘hero’. (4)

After a variety of almost incredible adventures, he set off (perhaps inevitably) for Britain and the European war.

The First World War – with the BEF

On 4 November 1914, Thord-Gray was commissioned Major, 2nd-in-command, 15th Northumberland Fusiliers. He would later state: ‘Owing to the constant illness of the CO I practically raised and trained the battalion’. (5) On the 21st he was writing to ‘Earl Kitchener’, from the King’s Head, Darlington. ‘I have in nine campaigns tried to bring myself up to date and have studied and worked with more than six different armies in the field’, his self-serving trumpet blew. ‘I have commanded a cavalry brigade in time of war and was also chief of staff to an army corps’. His stall thus set out, he continued: ‘May I venture to say that my somewhat extended experience is wasted as 2nd in command; my work is too limited, hence my bringing these notes to your attention’. What Horatio Herbert thought has not survived. On 18 June 1915, however, Thord-Gray took over command of 11th Northumberland Fusiliers, and in a typical comment writes of ‘putting the same into shape’ – this would have indeed been the task of a CO installed just prior to a unit going overseas.

The Fusiliers landed in France on 25 August and went into the front line first on 10 September. On 13 November the unit War Diary recorded ‘Commanding Officer went into Rest Hospital at Steewerck’, and subsequently on the 23rd: “Lieut-Col I Thord-Gray commanding the battalion ordered to proceed forthwith to England’. (6) Thord-Gray stated that he resigned his command for ‘grave reasons’ and ‘with the view of trying to improve matters’. He had run foul of GOC 66 Infantry Brigade, Eric Pearce-Serocold, who had reported negatively to First Army HQ on him – ‘He has not carried out all my orders to the letter in spite of his assertion that he has done so’, adding: ‘He prefers to employ his own methods, which are sometimes at variance with mine, and do not harmonise with those which have been generally accepted in the British Army. I do not consider him a reliable commander’. Confronted by Thord-Gray, the Brigadier amended one of these sentences and replaced it with ‘I feel that he lets his zeal outrun discretion at times’. Thord-Gray alleged, however, that Pearce-Serocold reverted to his original comments (which certainly lie on file). One suspects Pearce-Serocold’s remarks were, in large part, accurate. Sir John French, writing on 21 November, was of the opinion that ‘I do not consider it desirable to retain the services of that officer with the Forces in the Field’, continuing: ‘I recommend that employment be found for Lieutenant-Colonel Gray with Colonial troops’. Lieutenant-General William Pultney, III Corps, had also recommended ‘employment in the East’. All concerned wanted him off the Western Front.

Thord-Gray gave his own account of his time in France. He complained that on his arrival there was ‘not a single map of the trenches in our division’ (the 23rd); and claimed that he ‘surveyed’ the entire divisional front and made a scale map. He stated that he wrote ‘detailed standing Trench Orders’ for the unit. This is verifiable – they ran to a number of pages and were eminently sensible. Whether his claim that they became the division’s standard or not is unverifiable. Probably close to the truth is his statement that at Brigade conferences ‘I gave my opinion … perhaps, a little too frankly’. He conceded that`my outspoken manner on such occasions did, I think, cause an ill feeling towards me on the part of the Brigadier and I fell out of grace'. He resigned, he claimed, about criticism of his unit over ‘a small matter of braziers’. ‘The straw which broke the camel’s back appears in the name of 'braziers', but this was not the real reason’, he later wrote.

The now unemployed Thord-Gray wrote on 28 December to the Military Secretary at the War Office: ‘Would you kindly inform me whether you have any objection to my offering my sword to France, Belgium or Serbia’. He was just the man to do so, of course. Instead, however, on 10 January he wrote to the Australian High Commissioner asking for ‘an appointment with the Australian Forces’. He was, however, given command of the 26th Battalion London Regiment (London Gazette 11/02/1916) which commission he resigned on 10/05/1916 . This battalion was short-lived in its existence (11/02 to 29/02/1916 – James’s ‘British Regiments’ does not list it). Thord-Gray’s account was that it was to be raised from ‘men from the colonies’ and that the High Commissioner for South Africa objected to the potential clash with the Colonial recruiting offices in England. This would, at least, be consistent with the belief he should serve with Dominion troops. (7)

Secret agent? But for whom? German spy?

In March 1917 MI5, describing Thord-Gray as ‘this most persistent person’, records that he had now made an ‘application’ (from New York) to act as ‘an agent for the British Government in the position of Intelligence officer with a sum of money at his disposal to counteract German intrigue’, which was stirring up the Mexicans to mass on the US border. MI5 added that he ‘has a somewhat exaggerated idea of his powers and importance’, and ‘quite unreliable’. The first part of these comments, at least, no doubt contained some truth.

The British Military Attaché in Stockholm in 1921 confirmed that ‘the reports on his visit to Mexico were submitted through Captain Gaunt, British Naval Attaché in Washington’. This seems to confirm the idea that Thord-Gray was acting as a secret agent, but with exactly what authority is unclear. With his usual chutzpah, he claimed to have ‘influenced the military party under Carranza not to concentrate their forces in a move against America which the Germans wanted them to’. This may well have been the sort of role that he fulfilled for the Americans in 1913-4. He never claimed to be an agent of the British government, however, describing going to Mexico in 1916 under his own steam, and the dating of MI5’s description of his application means it may have been made post hoc.

Yet at the same time as seeking to be an agent for Britain, Thord-Gray was under investigation ‘of the suspicion of his connection with the German Secret Services in America’. This is curious if he had officially acted for the USA in Mexico in 1913-14. His biographer, Stellan Bojerud, states that Captain Hopkins US Navy solved the issue in 1921 – Thord-Gray had been confused with one Colonel Newham F. Gray, a German agent operating in New York in 1914-1915.(8) Bojerud describes ‘a large-scale' security operation (though this may well be an exaggeration), believing that this was the reason that Thord-Gray’s commission on the unemployed list was only Gazetted that year. A letter from Captain Hopkins in his officer’s file, however, dates the uncovering of the confusion before the end of September 1916.

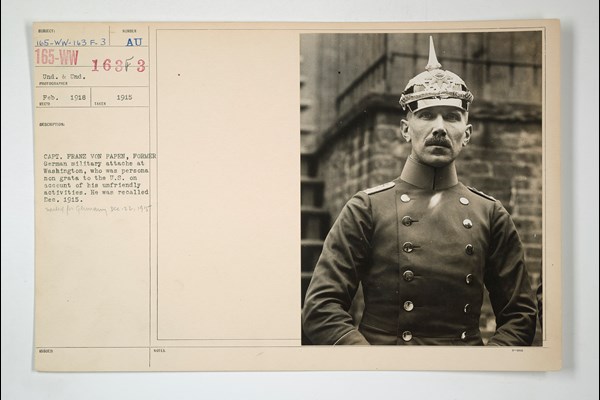

Thord-Gray’s difficulties certainly did not end there. An investigation of the Military Intelligence Branch US Army files in 1918 yielded the comment ‘Colonel Gray seems to be a soldier of fortune whose nationality and loyalty, not only to the cause of the United States but also to the Allies in general, has been questioned very often’. MI5 finally observed that Thord-Gray ‘has been under suspicion though nothing has been definitely proved against him’. It was later (almost certainly fallaciously) denied that he was ‘under the suspicion of being a spy’ and that his complaint that he could not return to the UK (he was then in New York) was false. MI5 confirmed, however, that he had once been detained at Dover in 1920 en route to Stockholm. ‘The Immigration Officer had my name on the “suspect list” as a German and a dangerous person’. Indeed, even later than this, the Americans were still investigating Thord-Gray as an ‘alleged assistant to Captain von Papen’, an allegation almost certainly untrue.

More broadly, his name change from Hallström to Gray raised suspicion, and it was ‘understood that his brother is in the Swedish Army, and has to do with interned Germans’ during the war’. His nationality (and hence his loyalty) was opaque (although he himself claimed British nationality since 1897, registered in the Cape). Indeed, he had fought for the Germans in South-West Africa. In considering all this, and taking into account his provision of detail for whom he had fought and where, it might be thought that Thord-Gray had probably played too many sides against the middle by this time in his life.

The US Army (again)

In late 1916 Thord-Gray was appointed Inspector to the Imperial Munitions Board, Montreal, Canada. He was ‘discharged on the spot’ when the Canadians asked London about his credentials. Displaced to New York, he attempted to join the American army in 1917 via a backdoor route, being appointed brigade commander in the aborted Theodore Roosevelt Division, forming a ‘British American Brigade’. An undated press cutting in his officers’ file described at this time as ‘on sick leave’ (implied from the British Army) and ‘busy compiling a list of the young Britishers engaged in business in the States. Already a large number have expressed willingness to serve’. The project was abandoned, but in May 1917 there arrived a letter from the War Office; ‘Colonel Thord-Gray has a bad reputation with the British and recommends that the American Government have no dealings with him’.

The Canadian Army

His whereabouts in late 1917 are unclear. In 1918 he was ‘Chief Military Speaker’ for the United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation, National Service Section, a job that was likely not unduly onerous, although he describes ‘speeding up production and strike breaking’. He left to join the Canadian Army, despite having been bounced out of the country the previous year, was commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel on 24 October 1918, and was sent to Siberia in a staff post at Base Headquarters – Transportation & Information. This post was, no doubt, unexciting to a man of action.

The White Russians

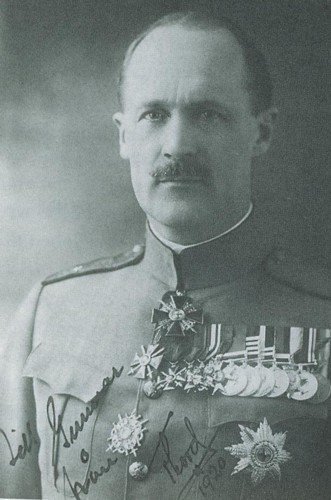

On 15 February 1919 Thord-Gray resigned, and joined the White Russian Forces, under Admiral Alexander Kolchak, then recognised as the Supreme Ruler of Russia by the Allies. He served as ‘Colonel of Cavalry and aide-de-camp’, and ‘acting Director of Organisation’ to General Radola Gajda of the Czechoslovak Legion.

He then became Second-in-Command of the 1st Siberian Assault Division on 15 May 1919 and Adjutant General. Commanding it in heavy fighting, later as GOC, he was wounded at Omsk on 14 August 1919, and possibly not in battle – Thord-Gray claimed this was an ‘attempt of assassination by the pro-German party’. He became Major-General on 29 November 1919 and diplomatic/military representative of the provisional Siberian government. As part of this he was involved in the sale of gold reserves to foreign banks. He was captured by the Soviets at the fall of Vladivostok on 29 November 1919, but was allowed to leave for Japan and the USA on 3 February 1920. The wiley Thord-Gray had the gold receipts in his pocket on departure – one receipt for 146,946 dollars dated 17 January 1920 is preserved in the Royal Library, Stockholm.

The banker

With no one to account to for the gold, Thord-Gray later claimed the money and set up I.T. Gray & Co, an investment bank located at 522 Fifth Avenue in New York City. One source has suggested that he was wounded in the head in 1921 in an attempted coup d’etat in Portugal, and consequently awarded the Spanish Isabella Catolica and San Fernando medal.

The Columbian Revolution

His last mercenary service was as a Lieutenant-General in the Revolutionary Army of Venezuela in 1928, contesting dictator Gen Juan Vicente Gomez. After this ended in failure, he returned to Sweden to write about his travels and archaeological discoveries. The Swedes would award him the Order of the Pole Star in the 1960s in recognition of his scientific work, following receiving his PhD from Uppsala University.

The American military once more

Returning (and finally) to the USA, on 8 April 1935 Thord-Gray was made a Major General in the Florida Militia, and Chief of Staff to the Governor. His commission was reactivated in 1942, and he was apparently tasked with organising counter-espionage in Florida.

Ivor Thord-Gray died on 18 August 1964 in Florida. He had ‘married’ five times, leaving children in various parts of the world; had written seven books including a Mexican (Tarahumara) dictionary, a book on the geology of the South African goldfields, one on Mexican archaeology, and trench warfare. He spoke English, Swedish, Spanish and Russian plus Bantu languages, Malaysian and Philippine Mindanao dialect, and the Tarahumara language. He had been attached to at least 10 different national or revolutionary armies in 16 or more conflicts. Seaman, planter, Major-General, gold thief, banker, intellectual, fencer and archer, his like will probably never be seen again.

Article by Peter Hodgkinson

Footnotes

1) Pictures variously from https://gmic.co.uk/topic/39260-great-medal-bar-of-a-swedish-officer-who-served-in-the-british-army/ ; and https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/29973-ltcol-ivor-thord-gray/.

2) TNA WO339/13665 Officers’ Services, Lieutenant-Colonel Ivor Thord-Gray.

3) Adolfo Arrioja Vizcaíno, ‘El sueco que se fue con Pancho Villa : aventuras de un mercenario en la Revolución Mexicana’ (2000).

4) https://www.mexicanist.com/l/ivor-thord-gray/

5) Lt-Col Roddam John Roddam – the 15th would become a reserve battalion and lose its identity in September 1916.

6) War Diary, 11th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, TNA WO 95/2182/4

7) Thord-Gray claimed that on 4 June 1915 he had already offered to ‘raise a Colonial Brigade’.

8) https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/29973-ltcol-ivor-thord-gray/. Stellan Bojerud, Ivor Thord-Gray - Soldat under 13 Fanor (Stockholm: Sivart Förlag AB, 2008) – not available in English.