Lewes War Memorial by Dr Graham Mayhew

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Lewes War Memorial by Dr Graham Mayhew

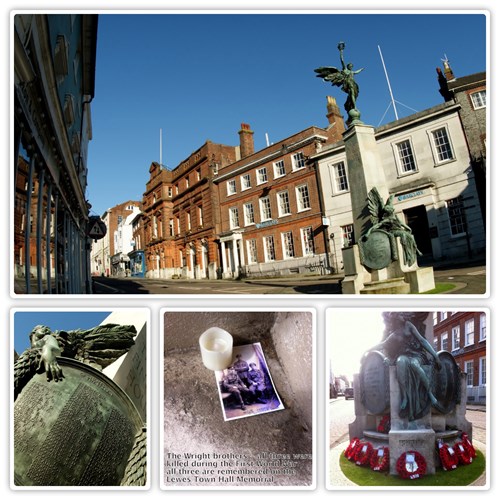

Erected in 1922, following a design competition judged by the Slade Professor of Fine Art at Cambridge University, Lewes War Memorial stands twenty-seven feet high in the middle of Lewes High Street, at the top of School Hill. Its Portland Stone obelisk is topped by a bronze winged victory looking straight down the hill. At its foot are two more bronze statues: the one on the east represents Peace, while the one on the west represents Liberty. Between them, on each corner, are four bronze medallions with the names of 236 of those who died during the Great War, as it was then known. It is one of only a handful of Grade 2 star listed war memorials in the country.

In the years leading up to the memorial’s unveiling, Lewes Town Council sought the names of the fallen from friends and relatives of the deceased, who were required to complete forms drawn up for the purpose, giving the details of each of the deceased. These forms still survive amongst the Lewes Borough archives in the County Record Office at the Keep, Falmer. However there are many names on the memorials in Lewes’s parish churches and on the Southover memorial which are not included on the main memorial. And there are many more individuals revealed by newspapers and other records whose names do not appear on any monuments in Lewes.

Two years ago I agreed to undertake a comprehensive review of the names inscribed on the memorial itself and also of those who for whatever reason were not included. Although my work is still far from complete, I thought that in this, the centenary year of the end of the First World War, as we now know it, that readers might be interested in reading about some of the men and the four women who lost their lives as a result of their service during more than four years of conflict. They come from every walk of life, every strata of Lewes society and their stories provide insights into Lewes in all its aspects in the years leading up to and during the war itself. I therefore approached Rupert Taylor at the Sussex Express, and agreed to write a series of articles which will run throughout this year on Lewes’s casualties of the Great War.

In 1914 Lewes was an industrial, commercial and administrative centre of 11,000 inhabitants, of which just over 5,100 were males, rather less than half of whom were eligible for military service (18-41 years of age from the introduction of conscription in January 1916, rising to 51 from April 1918). Amongst Lewes’s main employers were the Phoenix Ironworks, the railway with its vast goods yards (now Lewes Railway Land Wildlife Park), the gas, electricity and cement works, four breweries, three newspapers and printing works and the county and borough councils. Amongst the many professions attracted to the County Town were solicitors, accountants, surveyors and bankers as well as many white-collar workers employed as clerks in a wide variety of concerns.

Lewes itself had long ago spread out from its medieval boundaries, with newly built detached housing for the town’s elite on the Wallands and industrial housing for the working classes in the terraces north of the High Street, particularly in North Street area around the Naval Prison and the ironworks. There were also substantial areas of working class terraces in the Cliffe, Southover and Western Road. Many of these poorer areas were liable to flood and suffered greater levels of pollution by their proximity to industry, their inhabitants often suffering a variety of bronchial and other diseases, malnutrition leading to shorter physiques and shorter lifespans than those who lived in the more fashionable parts of town. Most working class Lewes recruits, for example, were between 5 feet 2 inches and 5 feet 5 inches tall, compared to those who became officers, drawn almost exclusively from the middle classes, who were usually between 5 feet 8 inches and 6 feet tall.

Within days of the outbreak of war on 4th August 1914 almost 500 Lewes men had either volunteered or been called up as reservists, and within a year over 1100 names appeared on the Lewes Roll of Honour of those serving with the colours. But despite these numbers more were continually needed as the carnage of modern warfare took their toll; and by December 1915 plans were in place for compulsory conscription into the armed services. For the remainder of the war the regular meetings of the Lewes Military Tribunal, which heard individual appeals against conscription, paint a picture of an ever-diminishing pool of suitable male recruits as commerce and industry struggled to find replacements, often for highly skilled operatives, not all of whom could be replaced by women, for whom the war undoubtedly offered employment opportunities previously unheard of.

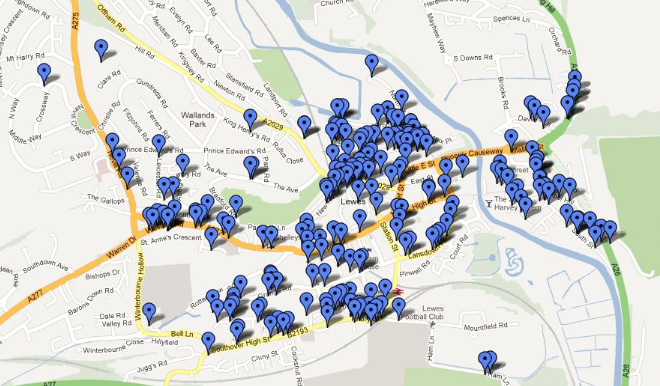

Where Lewes men who served and died in the First World war had lived (Google map pinned by Steve George)

Meanwhile the local death toll rose from 17 killed by the end of 1914 to 65 a year later, 140 by the end of 1916, 240 by the end of 1917, 350 by the end of 1918 with a further 30 war related deaths by the time the war memorial was unveiled in September 1922.

By the time of the Armistice on 11th November 1918 somewhere approaching 2,000 Lewes men had joined the forces, of whom 350 had died, with many more to follow from wounds, gas, diseases caught in the trenches and from general debilitation as the longer term effects of military service took their toll. At least as many again came home to Lewes with limbs missing, serious injuries, permanent lung damage due to gas, disfigurement and mental disturbance, often the effects of shell shock. At least two died in asylums and several Lewes soldiers committed suicide.

All of which makes the fervent desire for peace evident throughout the nation in the 1920s and early 1930s and the desperate attempts at appeasement of Hitler in the years leading up to World War II easily understandable. Compounding the actual loss of loved ones was the daily visibility, in Lewes as in every community throughout Britain, of shattered minds and bodies for years to come.

Dr. Graham Mayhew is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and was organising tutor in history at the Centre for Continuing Education, University of Sussex, where he taught for 33 years and at the Open University for 29 years. He studied history at York University, living in both York and Oxford.