‘Light Sewings’ and the British War Effort

Whenever I come across an example of the inordinate amount of time it seems to take in modern Britain to repair or replace even modest pieces of infrastructure, I find myself thinking about the length of the Great War. The conventional view is that it was a ‘long war’. It was not, in fact, particularly long, compared both with wars that went before and those that came after. Britain’s Great War lasted for fifty-two months or 1,560 days.[1]

When you think of what happened in those fifty-two months, the British war effort was little short of incredible. I used to undertake an exercise with my students at Birmingham University. It went like this: The British government has stumbled into a major land war in Europe against one of the world’s greatest military powers. How well-equipped was it to meet this challenge? What changes did it need to make in order to prevail over its enemies? We would then go round the table. The students would come up with the obvious: raise a bigger army, train it, clothe it, equip it. But as we continued to go round the table the complexities of bringing this about became more and more apparent, an inter-connected web involving state power, legal (and occasionally illegal) authority, labour supply, labour relations, manpower planning, raw materials, manufacturing, construction, skills, food, forestry, national and international finance, imports, shipping, insurance, research and development, and transport. And more. No student, however bright, came up with the eventual need for Box Repair Factories. My discovery of the Box Repair Factory at Beddington, near Croydon, in the pages of the Official History of the Ministry of Munitions was a seminal moment in my understanding of the Great War and what it took to win it.[2]

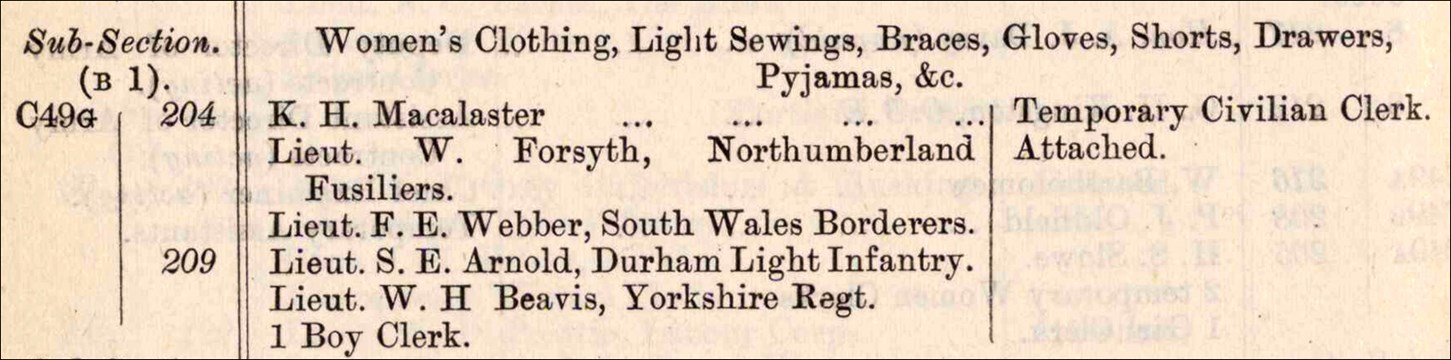

I had a similar revelation recently. My friend Mick Rowson drew attention to Findmypast’s making available some publications from the London Library. Among these was the War Office List, including the years 1917 and 1918. I mentioned this to my collaborator Andy Johnson. Andy has what Professor John Vincent called ‘the historian’s eye’, the ability to spot the significance of the apparently insignificant. No sooner than you could say West Bromwich Albion, than Andy’s eye fell upon a Sub-Section of the Department of the Surveyor-General of Supply, ‘Women’s Clothing, Light Sewings, Braces, Gloves, Shorts, Drawers, Pyjamas, &c.’ I think that what really caught Andy’s attention was that four of the named personnel were military officers. A quick check on one of them revealed that he had served abroad. This provoked the questions: how did these men get there? and what did they do?

First, some context is necessary. The Department of the Surveyor-General of Supply was a Department of the War Office. It was responsible for the ‘Provision of all stores, supplies and works services required by the Army, other than those specifically assigned to other Departments, and of all stores and supplies other than Munitions required by the Allied Governments, so far as they are purchased in this country’. The Surveyor-General of Supply (S.G.S.) was Andrew Weir (1865-1955), later Lord Inverforth, a Glasgow shipowner, one of the ‘Men of Push and Go’ whom Lloyd George installed at the heart of the British administrative state.

In March 1917 Weir had been tasked with reporting on the organization of the supply branches of the army. He recommended the appointment of a Surveyor-General of Supply with a seat on the Army Council, the supreme administering body of the British Army. His recommendation was accepted and he was given the job, which was unpaid. The Department consisted of two branches, the Demands Branch and the Contracts Branch. It is with the latter that we are concerned.

The Director of Army Contracts (D.A.C.) was Henry Heath Fawcett CB (1863-1925), a career civil servant. The Contracts Branch had seven sub-divisions. DC1 was responsible for ‘Hardware, Cutlery, Engineers’ Stores, Wire, Earthenware, Timber, Woodware, Brushware, Basketware, Oils, Chemicals and Tools’. DC2 was responsible for ‘Purchases and Sales of Provisions, Forage, Hospital Supplies, and Coal’. DC3 was responsible for ‘Building Works (Purchase and Sales of), Building Stores and Materials, Machinery, Pontoons, Boats and Vessels, Bridging Stores, &c’. DC4 was responsible for the ‘Purchase of Made-Up Clothing and Head-dresses, Buttons, Badges, and Miscellaneous Pimlico Requirements, Officers Clothing Schemes’.[3] DC5 was responsible for ‘Medicines, Drugs, Chemicals, Disinfectants, Surgical Dressings, Surgical Apparatus and Appliances, Electro-Medical and X-Ray Apparatus’. DC7 was ‘Statistics’.[4] DC8 was the ‘General Section. Parliamentary and General Questions; Staff Records, Recruiting, Labour Supply, and Wages Questions; Liaison Duties with Ministry of Labour and Ministry of National Service; Issuing and Scheduling of Tenders; Notation of Trades Books; Revisions of Trades Lists, &c’.

The ‘Women’s Clothing [and] Light Sewings’ sub-section was part of DC4, based in Grosvenor Road, Victoria. It consisted of a Temporary Civilian Clerk, four ‘attached’ army officers and an (unnamed) Boy Clerk.

The Temporary Civilian Clerk was Kingsley Henry Macalaster. His route into ‘Light Sewings’ is somewhat obscure, but it is possible to make an educated guess. He was born in 1886 in Dorking, Surrey, and so was of military age, but there is no evidence of his ever having served. His father, John Muir Macalaster, was a railway contracts manager and later Secretary of a rubber company. The family was quite well off. Kingsley was educated at the public school, Lancing College, where he played cricket. This gave him three ticked boxes when it came to obtaining clerical employment: he was available; he was educated; and he was a man at a time when ‘clerking’ was predominantly considered a male occupation. Even so, for someone of Macalaster’s background a temporary clerking position hardly seems to have been the summit of ambition. Macalaster almost certainly regarded the position to be as temporary as did the War Office. It appears to have been a convenient arrangement for a ‘resting’ actor.

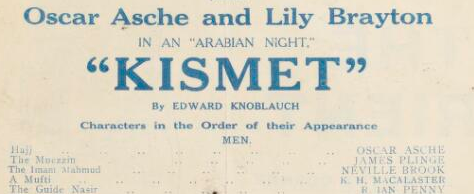

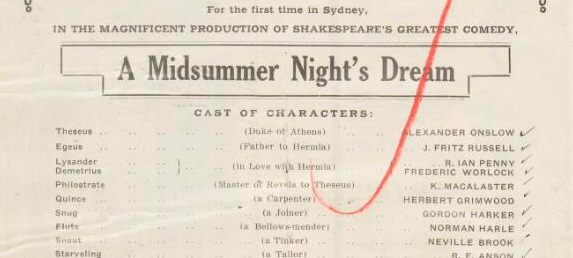

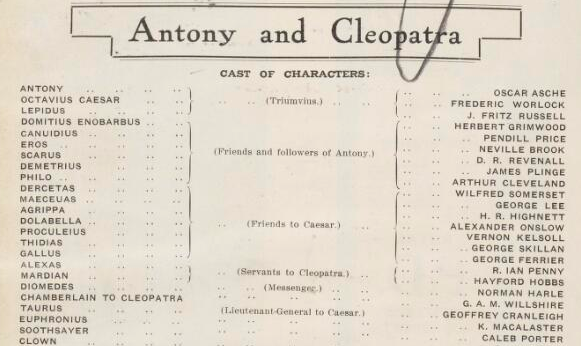

The 1911 Census captured Macalaster boarding in Chiswick with Margaret Mowbray Stevenson (1883-1924) and her brother Thomas Alan Humphrey Stevenson (1893-1972). Miss Stevenson and Macalaster were both recorded as ‘artists’ models’; her brother was a ‘dramatic student’. The brother’s ‘occupation’ looked suspiciously like a clue. And so it proved. I eventually found Macalaster as a member of the Oscar Asche/Lily Brayton theatrical company that toured Australia and South Africa in 1912-13, mainly putting on Shakespeare plays.[5]

Working in the War Office was doubtless more remunerative than being an artist’s model, but it played the same role. However, Macalaster does not seem to have resurrected his acting career after the war, at least not with any success. By 1921 he was a dealer in foreign stamps, an occupation he maintained. In 1939 he was a stamp dealer’s manager. He died in 1968, aged 81.[6]

Lieutenant Sidney Edmonds Arnold (1882-1921), Durham Light Infantry, was born in Stoke Newington on 11 October 1882, the son of Nathaniel Arnold (1856-1928) and Eliza Ann Edmonds (1856-1888). His father was a man of independent means, who left £16,209 5s 1d at his death. Sidney Arnold was educated at Ealing Grammar School and the City of London School. When he attested on 17 October 1914, aged 22, he described himself as a ‘clerk’, but he actually seems to have been an accountant.[7] He joined 23rd (Service) Battalion Royal Fusiliers (1st Sportsman’s). Sidney served with the BEF in France from 16 November 1915 until 10 May 1916, when he was invalided home with pneumonia. He transferred to 5th (Reserve) Battalion Royal Fusiliers on 5 September 1916, from which he was selected for officer training at No 8 Officer Cadet Battalion (Lichfield) on 2 December. Sidney was commissioned in the 15th (Service) Battalion Durham Light Infantry on 27 March 1917, but never served with this unit abroad. On 12 May 1917 he suffered gas poisoning while under training at Whitburn in Co. Durham. As a result, he complained of debility and cardiac problems, but the latter were thought to be ‘more symptoms of neurasthenia’ and he was advised to seek advice at Palace Green ‘Special Hospital for Officers’, London. Successive medical boards reported him fit only for light duties and on 25 September 1917 he was posted to the ‘Contracts Department, War Office’, where he remained until released from military service in January 1919. He continued in civilian life to work as a ‘clothing manufacturer’s manager’ as well as being in receipt of an army pension. He died on 7 March 1921 from acute tuberculosis of the lungs and heart failure, aged only 38.

Lieutenant William Herbert Beavis (1894-1962), Yorkshire Regiment, was born on 18 September 1894, the son of Frank Herbert Beavis (1872-1949), a carpenter and joiner, and Amelia S. Bickell (1872-1940). Prior to the outbreak of war he was a student at London University. He was commissioned from London University OTC into the 1/4th Battalion Yorkshire Regiment TF on 9 April 1915. He landed with the battalion at Boulogne on 18 April 1915, but was seconded for service with the Machine Gun Corps on 10 April 1916. It was while serving with 46 MG Coy, 46 Brigade, that he was wounded by a shell splinter in his left eye at Ypres on 1 August 1917. This necessitated the removal of the eye. At a Medical Board held on 30 November 1917 it was reported that he had been fitted with an artificial eye, that the left eye socket was healthy, that he was ‘suffering but little pain’ and was now able to read and write. He was duly seconded for duty with the Director of Clothing Contracts on 1 January 1918. The army evidently appreciated his abilities and he was chosen to join the Army of Occupation in Germany, for which he received the Army of Occupation Bonus. He was not released from military service until 17 June 1920. It is not known what career path Beavis intended before the war, but his time in ‘Light Sewings’ was not wasted. He became a career civil servant working in Disposal and Liquidation (1921) and the Ministry of Supply (1939). He died on 9 November 1962, aged 68.

Lieutenant William Forsyth (1883-1935), Northumberland Fusiliers, was born on 21 November 1883, the son of Peter Forsyth (1859-1924) and Wilhelmina Wilson (1858-1931). Prior to the war Forsyth was a Company Director and Secretary in his father’s clothing business in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. He had some military experience as a Sergeant Instructor in the Newcastle Citizens Training League[8] and later with the Durham University OTC, which he joined on 8 November 1915.

He was accepted for admission to No. 5 Officer Cadet Battalion (Cambridge) on 14 March 1916 and commissioned in the 8th (Service) Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers on 5 August 1916. His service at the front was terminated by ‘trench fever and dilated heart’ on 1 July 1917. A series of Medical Boards declared him to be fit for light duties at home only and on22 November 1917 he was seconded to the Contracts Department, where he remained until after the end of the war when he was gazetted as having relinquished his commission on the grounds of ill-health contracted on active service. He returned to work with Geo. Charlton Ltd. Tailor & Clothier in Newcastle. He died on 15 July 1935 from ‘cardiac failure; pulmonary oedema; cerebral thrombosis; [and] arterio-sclerosis’, aged only 51.

Lieutenant Frank Edward Webber (1893-1963), South Wales Borderers, was born on 8 October 1893, the son of Charles Webber (1856-1939), a coal tipper at Barry Docks, and Hannah Martin (1861-1959). He was educated at Barry County School, Glamorgan, and prior to the outbreak of war was an undergraduate at Cardiff University. He volunteered for military service on 15 September 1914 and joined the 21st (Service) Battalion Royal Fusiliers (4th Public Schools), seeing active service with the battalion’s machine-gun section. He was with the BEF from 11 November 1915 until 24 March 1916, when he was posted to No. 1 Officer Cadet Battalion (Denham) for officer training.

He was discharged to a commission in the South Wales Borderers on 5 August 1916, eventually being posted to the 2nd Battalion. He suffered a GSW to his neck and chest at Le Transloy on 28 January 1917. This rendered his left arm and hand ‘useless’. The army concluded, however, that he had a functioning right hand and arm and posted him to ‘Light Sewings’ in September 1917. He was finally released from military service on 3 June 1919. He became a clerk after the war, working for a commercial publishers and eventually becoming a newspaper manager. He was made OBE on 9 January 1946. He died on 21 April 1963, aged 69.

Anyone familiar with military administration, either through personal experience or at second hand, knows that it is often difficult to fathom. In the case of recruitment to ‘Light Sewings’, however, the army’s actions appear to be severely rational. Prior to the outbreak of war the provision of kit and equipment for the small British army was largely achieved ‘in-house’. The rapid expansion of the army meant that this was no longer possible. Provision had to be outsourced, initially to civilian companies with the requisite expertise, but then to other companies which could be ‘repurposed’. The favoured method employed by the government, pioneered by the Ministry of Munitions, was to establish local advisory committees. The Surveyor-General of Supply also appointed a Committee of Manufacturers to review patterns and specifications for Army clothing. These arrangements were all subject to contracts that had to be drafted, agreed, implemented and monitored. The work was important, requiring an eye for detail, some facility with numbers and, preferably, some familiarity with clothing production. In this light the recruitment of the four army officers appears not only fortuitous but also calculated. The fortunes of war had placed at the disposal of DC4 four men no longer fit for military service who could, nevertheless, be seconded for this important work and who had relevant expertise.

Acknowledgements: My thanks, as always, to Andy Johnson and also to Mick Rowson and Phil Tomaselli.

Notes:

[1] Counting 5 August 1914 as the first day and 11 November 1918 as the last.

[2] The Beddington Box Repair Factory was established in November 1916

[3] ‘Pimlico Requirements’ refers to the needs of the Royal Army Clothing Department, based in Pimlico, London. Its principal activity was the manufacture of uniforms.

[4] There appears not to have been a subdivision DC6.

[5] John Stange Heiss Oscar Asche (1871-1936) was an Australian actor, director and writer, now best remembered for the musical ‘Chu Chin Chow’, which ran for more than 2,000 performances, and which must have been seen by just about every British army officer home on leave from 1916 onwards. Elizabeth ‘Lily’ Brayton (1876-1953), a well-known actress, married Asche in 1898. Their company was formed in 1907.

[6] Macalaster Snr, like many nineteenth-century British railwaymen, spent some time in South America: his daughter Theodora, Kingsley’s older sister, was born in Montevideo in 1880. The time spent abroad by his father may have provided Kingsley with his interest in foreign stamps.

[7] On his application for a commission he is described as an ‘accountant’.

[8] This was formed after a meeting of prominent Newcastle businessmen on 6 August 1914. Many of its members would transfer to the 16th (Service) Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers (Newcastle Commercials).

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

This magazine provides updates on WW1 related news, WFA activities and events.

Access online tours of significant WWI sites, providing immense learning experience.

Listen to over 300 episodes of the "Mentioned in Dispatches" podcast.