Remembering Grandad’s war : Sergeant James Fleming

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Remembering Grandad’s war : Sergeant James Fleming

For many people interested in the First World War, initial enthusiasm can often be traced back to an old sepia photograph. What did ‘dad’ or ‘grandad’ do? It is a similar story for many members of this Association, and their research has provided some captivating first-hand accounts over the course of our 40-year history…

In 2015 one of our Lancashire members, Christopher Boardman, shared an article that he had unearthed about his grandfather, James Fleming, that had appeared in 1924 in a weekly publication called ‘Carbon’ – a title run by the Fletcher Burrows pits in South Lancashire, where his grandfather had worked both prior to and after the conflict.

Above: Sergeant James Fleming during his war service.

“Growing up I often heard stories about my grandad’s bravery,” explained Christopher. “I was only two when he died and unable to talk to him about his experiences, so finding any written literature was the only way I could recount his feelings during the war.”

He added: “A story about his time in the trenches at Christmas 1915 was the closest thing to talking to him. I have retraced his movements throughout the war and built a picture of his experiences, but his feelings can best be displayed by his Christmas story.”

The story that appeared in ‘Carbon’ saw his grandfather reminiscing about Christmas Eve 1915 with the 8th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment. At the time of the letter, the battalion were surviving in appalling conditions: the front-line trenches they were occupying said to be little more than frozen swamps. James, who was now a Sergeant, wrote the following…

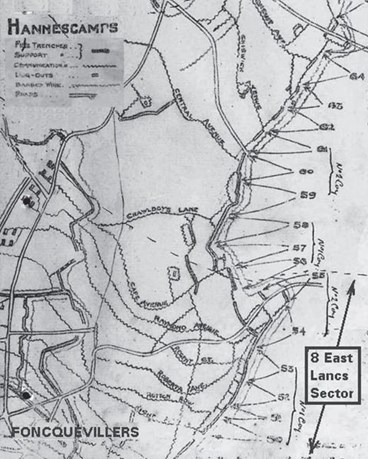

Above: A map showing the area in which the 8th Battalion were based in the winter of 1915.

Above: The Major who is mentioned in James’ account was Major Beauchamp McGrath, who was famous for this photograph of him struggling through a water-logged trench. He was killed in action in June 1916.

‘Cheerful homesteads, bright fires, tables laden with good food, sparkling wines, good old Dickens-and we had bread and pozzy and tea strongly reminiscent of the old story of the three men who argued as to the identity of a certain brew they were partaking of: one claiming it was tea, another coco, and the other coffee. So, the cook was appealed to - who indignantly declared that it was “bon soup”.

‘At six o clock I was ordered to proceed to the Btn HQ for an interview with the second in command. I left the front line trenches wondering what mischief was afoot, for our Major by no means belied the man who said that “All Majors are mad”.

‘On arrival at HQ in the village I was told that the Major was at dinner and would see me afterwards. In the meantime, I must wait in the Mess cookhouse - an order promptly obeyed, for the cookhouses are pleasant places to cold and hungry men. There I was regaled with dinner and rum - the Major’s orders – so the cook informed me. Thoughtful man!

‘Later on, I was shown into the Major, who was in command in the absence of the Colonel. He gave me a message of congratulation to convey to the men of my platoon for good work done a few days before: also an order to my OC Platoon that each man should receive a double issue of the wine “that cheers”.

‘As I made my way back through the village and into an orchard that led by a short cut to the communication trench, I was brought up sharp as a Jerry gunner began his strafe, and as I lay behind the trunk of a tree I heard a cry of pain and cursing voices from the village behind. Half an hour later, after a weary plod through heavy, clinging mud, I heard again the bellowing voice of the Jerry

humorist over the way, with his one-line hymn of hate, ”Johnny Bull, Bully Bif”, and a British voice in mocking reply, ”Ho, ho, puta sock in it”.

‘I gave my message to the indifferent men who listened unmoved as I related the Major’s words of praise-but they gave way to approving shouts of “Good old Mac” as I told them of the liquid happiness in store.

‘We drank to each other and the “Folks at Home” and called for a toast from little Bobby C, a wet, mud-caked figure, who had been on patrol between the lines. Bobby held the cup aloft, looked around the circle of grinning faces and said, “Sloppy Days”.

‘We “Stood To” at midnight as the shells whistled and screamed overhead. As I look back through the years I picture the scene as we “Stood To” in the dawn of Christmas Day, and I cherish the memory of the men with whom I stood and am tempted to say: “May the spirit of peace teach the heedless men

the folly of strife, by shining sword or malignant pen, breeding hatred, denying life, to warring hosts. And when men and women throughout the civilised world shall fully realise the bitter futility of war, they will surely rally to and support a League of Nations bringing Peace on Earth”.’

The good work that had earned the men extra rum rations had taken place on 22nd December and resulted in Private William Young being awarded the VC.

Above: The cover of the edition of the Bulletin (issue 103) in which the story first appeared.

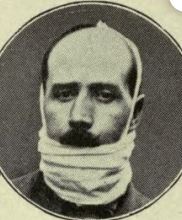

Above: William Young VC with his face bandaged after being shot through the jaw.

Young, a Scotsman and reservist had been a member of the British Expeditionary Force that had arrived in France in September 1914. Badly gassed, he had been sent home and only been for a short time (as part of a draft for the 8th East Lancs) when – as part of our writer’s platoon - he saved an NCO near Foncquevillers.

Young had been looking over the parapet of the platoon’s trench on the morning of 22nd December when he saw a Sergeant Allan stranded in no-man’s land. Allan had been wounded the night before on a patrol and, despite heavy enemy fire, Young did not hesitate in going out through the wire to help him. Ignoring Allan’s orders to leave him be, Young dragged the NCO back to safety - being hit twice in the process; one bullet shattering his jaw and another lodging in his chest.

Having got Allan back safely, Young walked close to half a mile to a clearing station near Foncquevillers to get his own wounds treated.)

Sergeant Fleming would be wounded himself the following year, on 26th June, in trenches north-east of Hannescamps: the Germans were bombarding the British line with artillery and rifle grenades when James spotted a shower of grenades land in his traverse and successfully averted injury to his men. He was wounded in the side and foot and evacuated.

Returning to his battalion in early 1917, and now promoted to Company Sergeant Major, on 31st May James was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his action in an attack near Monchy le Preux. His citation reads:

“He led his company with great courage, and when finally a withdrawal was ordered he remained till the last to see that it was properly carried out. He was three times wounded.”

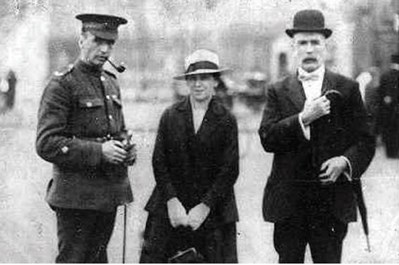

Above: James Fleming with his wife Emily and father William outside Buckingham Palace in 1918.

Above: James as an older man at a Remembrance Sunday event at Atherton, Lancs.

James was again returned to the front after hospitalisation– this time with the 11th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment - and in June 1918, near Vieux Berquin, disregarded his own severe wounds to shellfire, as well as the loss of his officers, to successfully lead two platoons to their objectives. As an acting Warrant Officer at the time, he was awarded the Military Cross and subsequently had it presented to him by the King at Buckingham Palace.

After the war James returned to the colliery where he had worked since the age of 16 and was employed as a chauffeur until his retirement in 1938. The following year, James was part of the British Legion Task Force and re-enlisted with the East Lancashire Regiment. After the Second World War he worked for the Admiralty prior to retiring and residing in Atherton, Lancashire.

James often led the procession to Atherton’s Cenotaph on Armistice Sunday. He died tragically in 1967 after breaking his neck in a fall at home.

Original research Christopher Boardman. Edited Dr Martin Purdy