'Roasting a sausage': Balloons, their crews, and those who shot them down

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'Roasting a sausage': Balloons, their crews, and those who shot them down

Although observation balloons had been used as early as 1794 the static nature of the conflict in the First World War provided the backdrop for the balloons to come into their own and play an important part in the war. The idiom ‘the balloon’s going up’ derives from the raising of a balloon signalling the beginning of an artillery barrage, guided by information provided by the observer in the balloon.

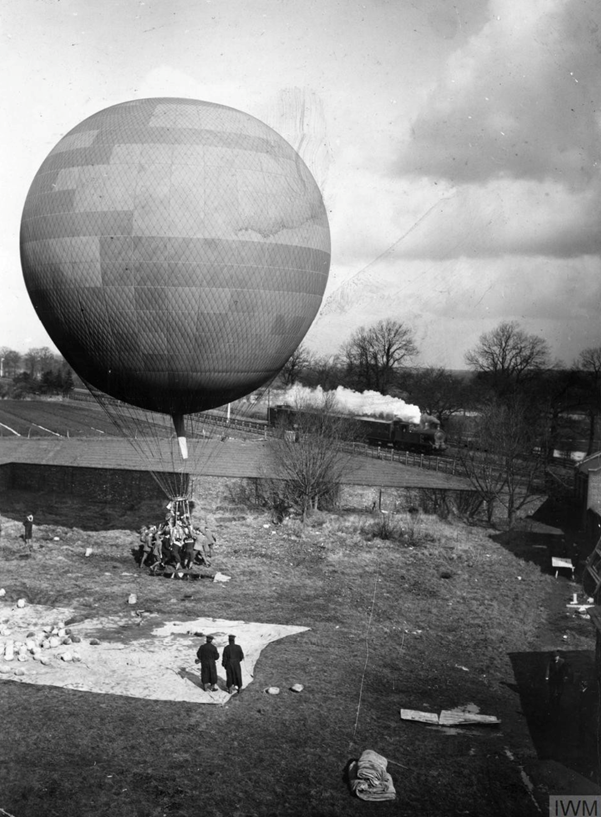

All the major protagonists in the conflict had developed their own style of balloons. At the start of the war the British were using a spherical balloon, but these were found to be unstable in high winds.

Above: Balloon ready for a flight at Farnborough Naval Wing, RFC. Photo IWM Q 73750

Meantime, in 1914 Albert Caquot designed a new sausage-shaped dirigible equipped with three air-filled lobes spaced evenly around the tail as stabilisers and moved the inner air balloonette from the rear to the underside of the nose, separate from the main gas envelope.

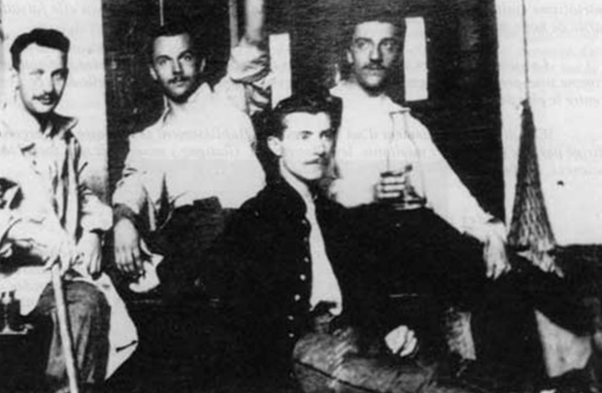

Above: Albert Caquot, the designer of the Caquot balloon

Above: A Caquot Balloon

All armies began using the kite balloons, also called captive balloons, as they were tethered to the ground. The Germans had developed the Parseval-Siegsfeld balloon – a slightly different design from the Caquot balloon – and this remained in use to the end of the war.

Above: A German observation balloon

Both the French and British called the balloons ‘sausages’ – the Germans called them ‘drachen’ (meaning dragon as well as kite) – there were also less polite words for them!

Typically, balloons were tethered to a steel cable attached to a winch that reeled the gasbag to its desired height (often above 3,000 feet) and retrieved it at the end of an observation session.

Above: German troops inflating an observation balloon. IWM Q54452

Above: A Caquot kite balloon ready to ascend. Note a motor winch and infantrymen hauling on ropes to hold the balloon down. Near Metz, 25 January 1918. IWM Q11892

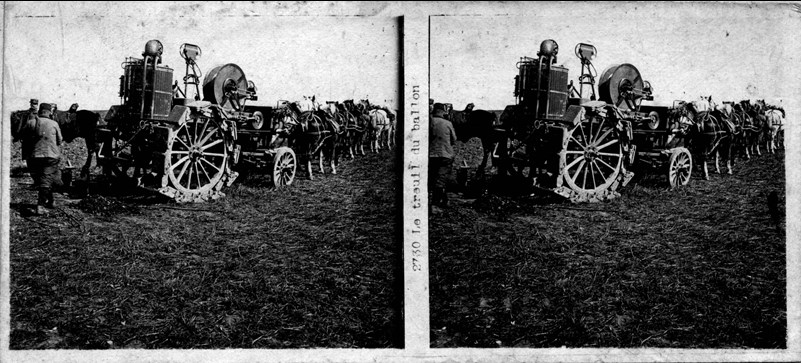

Above: A balloon winch. WFA stereoscope 2730. Note: There are numerous images of Balloons available in Stereoscopic format on The Western Front Association's website > Stereoscopic Images

Because of their importance as observation platforms, balloons were defended by anti-aircraft guns, groups of machine guns for low altitude defence and patrolling fighter aircraft.Balloons were highly valued for several reasons. They could hover at high altitudes and monitor enemy behaviour, spotting troop movements, new supply and munitions dumps, whether the enemy were stockpiling supplies and munitions, and if they were moving fresh troops forward to defend against an upcoming offensive or mount one of their own. Their other standard purpose was artillery spotting. Gunners often lacked a direct view of the enemy due to distance, weather conditions and geographical factors like ridge lines and hills. To accurately shell enemy targets they needed balloons to literally ‘call the shots’ by spotting where shells landed and directing gunners accurately on to important targets. Balloons were immensely valuable for intelligence gathering and artillery spotting. Protecting friendly balloons while destroying enemy balloons became increasingly important as the war ground on.

Above: Observers from a Balloon Company in the observation basket of a balloon ready to ascend. IWM Q12502

Working in pairs, the work of a balloon observer was far from glamorous as they stood in a wicker basket for hours at a time. They were in direct contact with headquarters and artillery batteries, so could direct changes in artillery fire as well as reporting on moves made by the enemy, even miles beyond the enemy line. Unlike pilots, balloon observers had parachutes.

Caption - Kite balloon observer descending by parachute IWM Q27522

One such observer was Captain Basil Hallam Radford, known more widely as Basil Hallam, who played Gilbert the Filbert the Knut with a K, alongside the American revue star, Elsie Janis in The Passing Show which played to packed houses throughout 1914 and into 1915. Cecil Beaton would later remember him as having “an attraction that was devastating to all ages and sexes”.

Above: Basil Hallam ‘Gilbert the Filbert’. Photo: The National Portrait Gallery, London

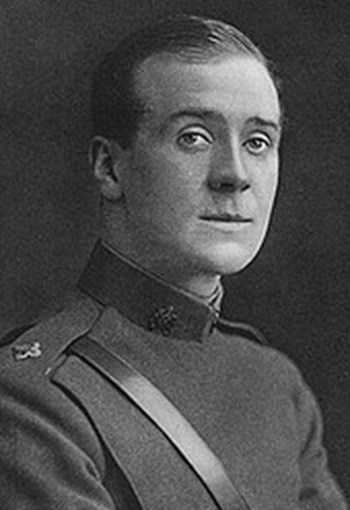

Above: Captain Basil Hallam Radford, No 1 Kite Balloon Section

In 1915, Radford left the show to enlist in the Royal Flying Corps. Serving in the Somme area, he was killed a year later when he fell from his balloon. Initially it was reported that his parachute had snagged on the balloon wires but this was later found to be incorrect. On 20 August 1916 Hallam was due to make an ascent with 2Lt P B Moxon. Unusually, a third man, Lt Geoffrey McCall. McCall, whose brother was a school chum of Hallam, had been invited along as a guest.

Sadly, and owing to a high wind, the balloon broke away from its moorings and began to drift towards enemy lines. The crew then proceeded to throw out their instruments and maps before planning to save themselves. Unfortunately, there were only two parachutes in the balloon and Hallam instructed Moxon and McCall to jump. This, of course, left him with the decision of either drifting out of control into enemy lines or to jump and hope.

For a short period, he was seen sitting on the edge of the basket before making his leap. The height was between three and six thousand feet and, not surprisingly, he didn't survive. His body was found on the Acheux-en-Amienois Road. In a letter to Lady Diana Cooper, Raymond Asquith, one of hundreds of witnesses to the tragedy, reported that Hallam's body was found dreadfully foreshortened and he was only identified by his cigarette case. Hallam’s grave is to be found in Couin British Cemetery.

Above and below: The headstone of Captain Basil Hallam Radford and Couin British Cemetery. Photo CWGC

Given the relatively unglamorous, although dangerous, nature of an observer’s work, it is unsurprising that those who sought to bring down the observation balloons were more feted. In 1915, aircraft began attacking enemy balloons – or “roasting sausages” as this was referred to. This was no easy task as they had to fly into enemy territory and take on a target protected by machine guns, artillery and aircraft. Many pilots who succeeded in ‘roasting a sausage’ were shot down in the process. Some were caught in the blast of the burning hydrogen.

The most prolific ‘balloon buster’ was Willy Coppens (image below) of Belgium, with a score of 34 balloons and 8 aircraft.

Above: A painting courtesy of Cranston Fine Arts entitled 'Balloon Buster Extraordinaire' by Stan Stokes. This shows Coppens approaching a German balloon.

Above: Again courtesy Cranston Fine Arts. This painting is entitled 'Last Kill of the Day' by Ivan Berryman. Coppens is shown here in Hanriot HD.1 No24 destroying a German Drachen balloon in the closing minutes of the day near Houthulst.

Above: The end of an observation balloon brought down in flames. Boyelles, 3 February 1918. IWM Q6492

Coppens survived the war, unlike the American pilot ace, Frank Luke, who had a score of 14 balloons and 4 aircraft.

Above: 2 Lieutenant Frank Luke

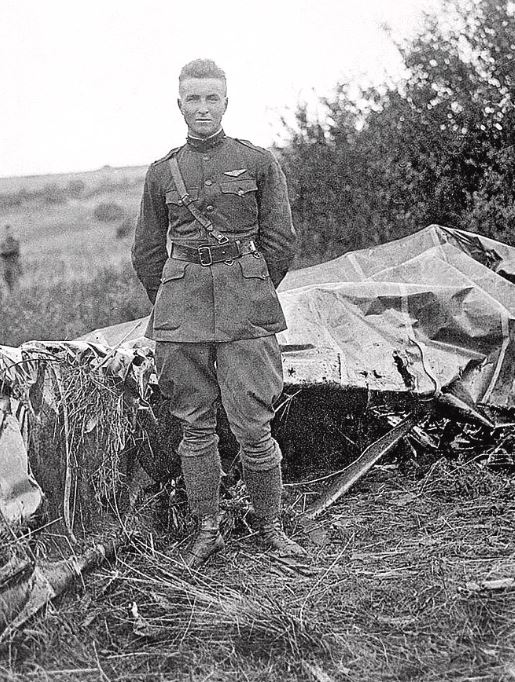

Above: Frank Luke on the occasion of his 13th kill on 18 September 1918

Just ten days after the above photograph was taken, Frank Luke was attacking an enemy balloon in the vicinity of Dun-sur-Meuse. Wounded by a machine gun bullet, he managed to land behind enemy lines but was killed by German infantry. He was buried by the Germans in Murvaux Cemetery but his grave was later relocated to the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. He was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Caption – Frank Luke’s gravestone

Article by Jill Stewart. Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Further reading:

The first French observation balloon of the Great War shot down