Tackling the six biggest classroom clichés of the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Tackling the six biggest classroom clichés of the First World War

Teaching the Great War and tackling the classroom clichés

Teaching History at School

Image from 'Peace and War International Relations 1900-1939 GCSE Modern World History by Steven Waugh and John Wright for EDEXCEL

Teaching the Great War

Originally published by the Journal of the Centre for First World Studies in 2002. This was posted with permission to the old WFA website 1 July 2015.

The Context of teaching the Great War

‘Marginalised’ is a phrase that could best sum up the position of teaching the Great War. This article will set out to discuss the issues surrounding the effective teaching of the Great War in modern State Schools. I am a teacher with an obsession about the Great War. The particular context in which I teach is an inner city multi-ethnic, co-educational school. I intend to provide a backdrop to the real issues affecting Great War delivery and to discuss the wider issues and what I have tried to do about them. This is no manual stating that everything I say is correct and will therefore apply anywhere but I know what has worked where I teach. I will also imply some criticism, at teachers, society and in particularly some organisations with mission statements about educating the public but then reneging on those duties.

The Structure of Modern Teaching of the Great War

When the National Curriculum was first set up in 1988, not surprisingly under a Conservative Government they wanted everything ‘great’ about Britain’s past to be included, nothing was to be left out and so there was an overburdened teaching profession coming to grips with the ‘stuff’ of history. There was an over emphasis on what to teach, the Great War was safe here because it was ‘in’. The result for many learners however was an historical understanding on the ‘1066 And All That’ model whereby history was boiled down to a populist viewpoint, with students ‘doing’ the Tudors: “Oh yeah Henry VIII he was the bloke with the six knives or was he the one who burned them cakes”? Common sense took hold and in 1995 a slimmed down curriculum was launched following the Dearing Report. The emphasis here was more on quality of the experience of the teaching and less on the ‘stuff’. But there was a problem in so far as there was now more freedom to choose; and in 2000 a further slimmed NC was launched giving even more scope for choice. The benefits were that History Teachers could select the areas where their expertise lay however the selection of a topic is always subject to the bias of the selector so if you have a specialist Medievalist on your staff then the diet the students would get is obvious.

The National Curriculum (England and Wales) is focused on Key Stage 3 (11-14 Year olds).

is at Primary level and KS 4 GCSE (old ‘O’ Levels). GCSE modules and courses are also selectable with several main course providers OCR, EDECXEL, AQA etc. Some providers offer thematic approaches but all offer modules, which are again subject to the bias of the selectors. ‘A’ Levels (Advanced Supplementary (AS) and Advanced Second Component (A2)) are no different so a student could go for their entire academic career without any Great War ‘stuff’ at all. As it happens the Great War does prove to be very popular but some of the quality of the delivery is open to question. So there is our first issue as teaching the Great War has its own structural problems; there has to be a teaching commitment to it in order for it to even be a topic in the first place.

Teaching the ‘Stuff’

The next key issue is the way in which the ‘stuff’ is taught. Question: “How do you teach students to be real historians”? Answer: “Give them some real history to do”. This all seems to be very obvious however teaching is subject to the same political pressures as any other public service and there is now a political raft of statutory and inspectable inclusions to accompany the ‘stuff’ for example: students with special education needs including the ‘gifted’, ethnic diversity, literacy, numeracy, ‘awe and wonder’ (doctrine of including a moment of a & w to engage the pupils with some fascinating disclosure to generate a love of learning), three part lessons, citizenship etc. So not only is a structural issue there is also political interference about what else should be included in each lesson.

Entrenched Assumptions

I am of course aware that I do need to talk about the Great War in this article and I do not want to come across as a moaning teacher but I do need to contextualise the historiography of history teaching. I attended a revision session for the most able students that I teach (some are ‘Oxbridge’ standard). A nearby ‘good’ school ran the session. I arrived with my students and we all had a good day although I was struck with one of the sessions when the Head of Department of the ‘good school’ said at the Great War revision workshop: “…and of course it was very clever of the German High Command to ask for an armistice before they were beaten”. This point was presented to the students as axiomatic! So this I hope illustrates my next point namely the difficulty of populist perceptions about the nature of the war that are ingrained in the fabric of ‘good learning institutions’. I have other anecdotes about leading universities presenting the Great War poets as some sort of predestined martyr clan. When surely they were soldiers first. John Bourne has gone on record many times about the state of journalism in certain newspapers with their coverage of the Great War and the ‘Donkeys’ etc. And it seems every year the same assumptions are trotted out by what I call the ‘futility’ school; the most recent public converts being none other than Richard and Judy. These populist views underpin the popular ‘disaster’ notion of the war. It was a disaster but in disaster the true qualities of leadership are shown. Britain was able to supply and sustain four types of army in the War (regular, territorial, volunteer and conscript) where is the credit?

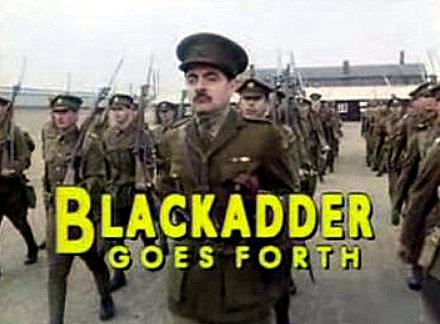

We are treated to a mass of Blackadder notions and misunderstandings.

I do not want to be misleading here as the ‘futility’ school is not a homogenous group, indeed it is a more a synergy of mis-conclusions held by a group of disparate factions including the left, the ignorant, some journalists and other self appointed authorities. Where do all these assumptions come from? It is down to several factors. Firstly some prejudicial press coverage, reliving the ‘1st July’ over and over again by supposedly educated people who are incapable of taking their thinking from a preconceived ‘futility’ comfort zone.

Why these views originated in the first place.

The basis of the ‘futility’ school is associated with the historiography of the War itself. The bandwagon of the 1930s has gathered allies through time. The story of history is governed by the time in which it is studied and the available evidence (or the evidence anyone is bothered to look at). It appears that since the end of the War the ‘futility’ school initially lead by Lloyd George et al. took hold of the debate, this was reinforced by the ‘Appeasement’ years further reinforced by documentaries such as Forgotten Men and the notion of the ‘Bomber always gets through’ coupled with the depression and the reflection of ‘what was it all for?’ The 1960s seemed to pour scorn on the army Commanders in their black and white photographs with their absurd facial hair. The arrival of Covenant with Death and Oh! What a lovely War being the populist icons of the 1960s ‘futility’ school.

Were our journalists brought up in this tradition?

Was the teacher in the ‘good’ school subject to the fashionable thinking of the day (the teacher was old enough)? In short there are structural problems with the teaching of the Great War but also, and more importantly revisionists are battling against a tide of prejudiced public opinion reinforced by a blinkered group of para-professionals and journalists who seek to tell the story of history without actually looking at any of the evidence. Which incidentally is now so overwhelming against the charges levelled at the British High Command as to be a national scandal. The ‘futility’ school has eroded much understanding of the War and now we have myth upon myth pedalled as truth.

What can teachers do about it?

Well for some nothing, comfort zones are good places to be as you can have a very clear view of the world where your assumptions and intellect are unchallenged and with initiative overload from central government I understand, to an extent, this view. However, historians should pursue truth so should see orthodoxies as versions of truth in fact we should not even use the term ‘orthodoxy’ as there is something static about the thinking behind that word. If we fail to educate our young to be able to challenge and do not give them ‘real history’ to do then we ourselves are pandering to the ‘futility’ school and untruth. The modern world for Britain is going to be a knowledge-based economy, we need people who can adapt, think and evaluate. The thinking is the key so it is imperative that we give the young real science to study and real history to consider. Therefore we must at least present both sides of the case; Terraine versus Laffin must be fought out in the classroom. In this way we at least generate thinkers even if they are not convinced by the arguments. They have to think about them in order to dismiss them.

Tackling the Clichés

There are always historical clichés. I have no doubt that a Tudor specialist would catch me talking about Henry VIII and his ‘six knives’ or telling some exaggerated story about religious genocide. Some clichés are more potent than others and whether it’s me being just too sensitive there appears to be some well established ones with the regard to Great War.

Classroom Cliché 1: Blackadder - shown in all classrooms in Secondary Schools. Classroom

Classroom Cliché 2: Gallipoli - (last 5 minutes) shown in nearly all Secondary Schools. Classroom

Classroom Cliché 3: Mud - taught in most classrooms under the assumption that the rain began on 4 August 1914 and did not stop until 11 November 1918.

Classroom Cliché 4: Tommy - having lied about his age is trying to come to terms with not only the weight of his equipment but also the weight of having been duped into becoming a ‘victim’.

Classroom Cliché 5: Machine Guns - which only the Germans had, perfect instruments for skittling ‘Tommies’ who walked very slowly towards the enemy, most machine guns being used, of course, on 1 July 1916.

Classroom Cliché 6: Officers - all public school, and all stupid! (For historical validity clichés 5 and 6 are of course cross-referenced to Cliché 1).

These clichés are the product of the longstanding work of the ‘futility’ school and are very difficult to break down. If we want to create real historians who are in search of truth then we must give them ‘real history’. On this point the skill of Inquiry is the key. Why not give the students a hypothesis ‘Was Lloyd George a liar?’ Of course you would not give them his ‘Memoirs’ and ask for a synopsis- they are children. But there are ways and means of doing this. Another could be why did ‘Tommy join the War?’ Providing evidence of a range of ‘push pull’ factors- this avoids the over simplistic ‘Why did Tommy die in the horror of the Somme after walking very slowly towards the enemy?’

Why not put Haig on trial?

He understood accountability what did he have to be scared of? As long as the evidence is balanced what does it matter if a child finds the case for the ‘butcher’ most convincing at least they may be more receptive to balanced answers in the future than the dreaded alternative… ‘Haig was a butcher and here is the evidence’…. play Blackadder, ‘Look at how he sweeps up his soldiers!’ Why not in A' Level lessons using S.S 143 as evidence of tactics or is it that only purchased textbooks meet the criteria as evidence? Why not be provocative? Why not engage young minds in ‘A’ level English with ‘Was Great War poetry Rubbish?’ It is a failing in my view that some poetry is taught devoid of any historical context. Poetry is often deployed by the ‘futility’ school It is used as conclusive evidence and this is often subliminally deployed by unconscious converts to the ‘futility’ assumptions in a sort of ‘institutional ‘futilitarianism’. Journalists have often studied History and English Literature. Is there a link?

The greatest of all the teaching aids are the places themselves.

Properly arranged battlefield visits are the ultimate vehicle for a life long association. On my next school visit there will be students who are returning for the fourth time and some ex-students on their sixth (not including ones that they have arranged themselves). But there is a balancing act regarding the tone of the visit and the expectations you have from the students. If they perceive it as ‘work’ then they will not come, especially if the French Department are offering five days at EuroDisney - work not included! I am dismayed at the sight of some of the resources students have to carry and are forced to fill in at these greatest of places. It must be recognised that some students will never have been abroad before and the real motivating factor might be the thought of buying Belgian chocolates. The first rule in teaching is that you have to start at the level of the audience, which maybe very basic indeed, not because they are stupid but because of the fact they may have a very marginalised experience. Do not be too quick to judge.

‘J`Accuse’

There are those organisations that claim to want to educate the public but where is the evidence? Where is the support for teachers? Where are the downloadable resources off the Internet? Where are the offers of free courier/guides to accompany a school trip? Where are the offers to help construct an itinerary without taking over? Where are the branch education officers? Where are the artefact boxes for use in the classroom? I have seen some valiant efforts on the part of the Royal British Legion with the free education packs but this is more to do with fundraising and a clear ex-serviceman’s support agenda than challenging misconceptions of the War. I have also been the direct beneficiary of a Great War organisation sponsoring an essay competition for one of my visits but this is down to the energy displayed at the local branch level whilst the rest of the organisation shows no central leadership on their own mission statement. ‘Remembrance’ is something that is key to the survival of the memory of that generation. The truth about their endeavours needs to be told and retold to do nothing is to be complicit with the ‘futilitarians’ and their agenda of fraud.

Modern Learners. Students will not have met veterans of the Great War.

Therefore the formative influences regarding the power of that conflict are much lessened in the twenty-first century. There is now a generational distance. The veterans that remain are now so few and at least 102 years old so that it is not inaccurate to say that the war is beyond living memory. Something else that must be borne in mind is that students are different from the last generation. In fact it is a generational cliché to assume that every succeeding generation is somehow worse than the last one. I disagree, they are not worse they are just different. The modern learner has a shorter attention span – the average boy just 3 minutes, students laugh more than adults, on average an adult will laugh 30 times a day where as a child will laugh 300. So think about that when you are on the battlefields and assume that respect is not being shown when you see ‘high spirits’. I have written work from some this generation of students about ‘Remembrance’ that would make you cry. They ‘respect’ alright but they do not always conform to an adult’s sombre style (this is not an apology for bad behaviour, but there is quite a difference). Respect is something that is earned so why assume given the context above that the students know anything? Perhaps they don’t, isn’t that why they are there? The attitudes are quite different post visit. Effective learning is enhanced through experience, as we associate the learning to the experience. And we experience most effectively through participation. Therefore ‘Remembrance’ and the Great War cannot be an imposed experience-as a sort of ‘remembrance through proxy’. I have seen some pretty dire attempts at this at Thiepval etc when a well-meaning teacher is, in essence, conveying: ‘This is what I feel so you have to as well’. It simply does not work that way. It is all about tone, balance, preparation and realistic expectations, we will not nor should seek to develop a mind set of third generation veterans who stick forks in their legs on 11 November ‘to feel their pain’. There are also issues regarding the ‘imperial’ nature of the War that need to be contextualised this very important when you are coming from a multi ethnic school. There is much scope for this on the Western Front. The whole experience of teaching the Great War is a great leveller as all levels of understanding and cultural experience can be sensibly and sensitively catered for.

The Thiepval Visitor Centre and the theme park approach to the Western Front.

I notice that even Newfoundland Park has roped off areas and visitor Centre, even an un official ice cream hut at the side. Some of the most opposed to this ‘Disney-isation’ are the same ones who sit in Ulster Tower and the Hill 62 and 60 cafes, which were set up with the same commercialism in mind in the 1920s. It also seems to me that there are some who are self-satisfied in their piety about in the ‘good old days’ when you never saw anyone all day on the battlefields and rudely call casual visitors or school parties ‘tourists’. The Western Front is not theirs and I would defy them to call one of my 12 year old Year 8 boys a tourist when he lays a wreath on the grave of his great uncle in Arras and then that night reads the Exhortation under the Menin Gate in April.

Conclusion

The new generation need to remember but they cannot do it as we have done. There maybe is a need for a visitor centre on the battlefields of the Somme, and this will ensure that there is memory – it will provide a focus and a service, even if it is just some toilets. In fact, on reflection, I hope it gets packed; I hope they have to queue down the D929 to get to it because I would rather we (collectively) remembered in a modern and perhaps flawed way than not at all. After all it says on the memorial scroll given to the next of kin of the fallen: “Let those who come after see to it that his name be not forgotten”. Well this is like any statement if it is to be actionable it needs to have a process to accompany it, we need to ‘remember’ but we also need the young to do it.