The Centenary of the lone English oak at Gallipoli

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Centenary of the lone English oak at Gallipoli

In the Spring of 1922, as part of a unique act of commemoration, the parents of a teenager killed at Gallipoli took the sapling of an English oak tree in a bucket of water across the Mediterranean. One hundred years on and the sapling has grown into an enduring memorial to the sacrifices of hundreds of men from a close-knit group of old Lancashire mill towns.

Above: Picture of the tree 'then and now'

Second Lieutenant Eric Duckworth had not long since celebrated his 19th birthday when he fell during the battle of the Krithia Vineyard on 7th August 1915. Like many, his body was never recovered – but unlike most, his parents were wealthy and well-connected: and James and Mary Duckworth would use their influence to find out far more about the death of their loved one than the majority of those in a similar position could ever hope to discover.

Above: Second Lieutenant Eric Duckworth

Eric Duckworth had studied at Rugby School and was being prepared for a career overseeing the family’s thriving chain of grocery businesses when war broke out. He was immediately parachuted into his hometown Territorial Army battalion (the 1/6th Lancashire Fusiliers) as a junior officer.

Part of the East Lancashire Territorial Army Division (soon to be renamed the 42nd Division), the 1/6th recruited from the mill towns of Rochdale, Middleton and Todmorden. The officers’ mess was a tight-knit and socially interconnected group made up of ‘the great and good’ of these three neighbouring communities, and it was this interconnection that would ultimately facilitate Eric’s parents’ act of pilgrimage to the Dardanelles.

Above: Picture of 1/6th officers at Gallipoli

For within days of hearing of their child’s death, James Duckworth had managed to open a direct line of communication with the officers’ mess at Gallipoli. Within weeks, and with the help of the battalion chaplain, he had received a written first-hand account from one of his son’s wounded comrades(recuperating in a hospital bed in Malta) about Eric’s final moments.

Private Norman Howarth told them: “At 9.45am (on the 7th August) Lieutenant Duckworth led our platoon towards the vineyard, Many of the men were green reinforcements and halted at the first trench. About 20 men led by Duckworth kept charging the second trench. Only three men made it to the Turkish parapet: Private Porter, myself and Lieutenant Duckworth. Private Porter was about 20 yards to my left and he and I were busy shooting Turks. Private Porter crawled nearer to me and told me that Lieutenant Duckworth had been shot.”

When the smoke had lifted, Howarth said that he could see Duckworth 30 or 40 yards to his left, “sat on the parapet with his head on his chest”. The battalion chaplain later added that Duckworth had apparently been shot in the chest.

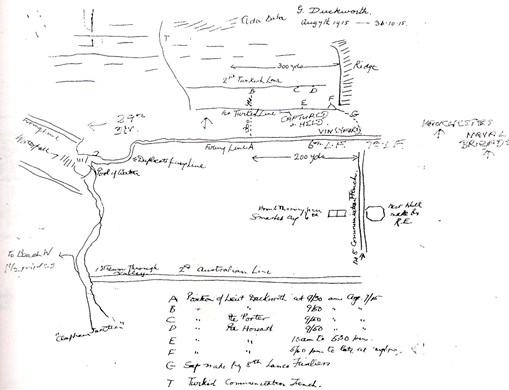

Duckworth’s parents asked Private Howarth to draw them a map of the spot where Eric had last been seen slumped in the Turkish wire, and it was this map that they took with them on their trip to the Dardanelles in March 1922. They set off on the 18th of the month, and although we do not know the exact date they arrived (their boat stopped at numerous countries en-route), it is estimated that they would have been on the peninsula in the last week of March or first week of April. We know that they were definitely home in Rochdale by April 15, when they made public the details of their pilgrimage in a self-penned item published in the Rochdale Observer newspaper.

Above: Picture of Duckworth Map

The intention of Mary and James Duckworth appears to have been to plant the tree sapling in the spot where Eric had fallen, but when they arrived at the site they found that it was being reclaimed for agriculture. Visiting a nearby Imperial War Graves (IWGC) cemetery they were deeply moved to discover that it contained men from Eric’s platoon – and furthermore, there were a couple of graves in the Redoubt Cemetery marked as ‘An officer of the Lancashire Fusiliers: Known unto God’. Could one of these be their child?

The parents decided to plant the tree sapling in this cemetery and attached a name plaque to it in memory of their son. They then gave money to the Turkish gardener employed by the IWGC to look after the tree, and in the ensuing years Eric’s younger brothers (who had been too young to take part in the war) went out to check on its progress and provide further financial support for the local gardeners.

James Duckworth explained on arriving home in Rochdale early April 1922: “We travelled by the coast and then turned inland… and Krithia village appeared on the right, a deserted pile of ruins. A few hundred yards further we turned right and stopped at the graveyard known as Redoubt Cemetery.

“We had no grave of our own to visit, having numbered with those whose boys fell in advanced positions, face to the foe and under such conditions that recovery was impossible. We found graves of a dozen or more of the men in our boy’s platoon – his (Eric’s) name would stand alongside those with whom he fought and for whom he so sincerely cared.”

Above: Picture of James Duckworth on a donkey at Gallipoli with Turkish guide and the sapling as he took in 1922

It is a testimony to the skills of the Turkish gardeners that the tree has continued to survive the same kind of challenges faced by the men who fought there in 1915: an oft-hostile environment typified by searing summer temperatures and below-zero winters.

Over the years the tree would grow in importance to the veterans of Eric’s battalion, and they would look forward to updates from his brothers about how it was faring.

After a reunion in 1935, the veterans were shown pictures of the tree, and one wrote: “In the Redoubt Cemetery (how peaceful it looks!) our comrades lie sleeping, and we were shown a fast-growing tree in memory of Eric Duckworth. Its leaves were a rich green and it looks so strong, as young Duckworth was. Ah yes, we must forget those days, but we cannot forget men like Duckworth and many more. We shall go on remembering them until the sun goes down for us.”

Article contributed Dr Martin Purdy

Martin co-wrote the book The Gallipoli Oak (Moonraker Books, 2013).