The Cotton-Mill Worker, the Stockbroker and the Flammenwerfer: The 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade at Hooge

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Cotton-Mill Worker, the Stockbroker and the Flammenwerfer: The 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade at Hooge

The small village of Hooge sits approximately three miles east of Ypres, and during the early stages of the Great War found itself situated squarely within the infamous salient, that which was so tenaciously held by the British throughout virtually the whole of the conflict. Following the Second Battle of Ypres, fought from 22 April to 25 May 1915, and the realignment of a new, shrunken front line as a result of the first successful deployment of poison gas by the Germans, the Hooge sector, incorporating – from north to south - Bellewaerde Ridge, Hooge village itself, Zouave Wood and Sanctuary Wood, was thrust into the firing line, now becoming the easternmost extremity of the whole salient. The forced withdrawal of the allies had left the front line running roughly north – south through the village, bisected by the Menin Road between Hooge and Zouave Wood on an east-west axis.

It was a focal point for much savage fighting that continued unabated throughout most of the war. Captain Francis Hitchcock of the 2nd Leinster Regiment noted that ‘Hooge had been continually under shellfire since the First Battle of Ypres in October, and the ridge […] had been captured and recaptured five times since April [1915]’ [1]. Ever since the end of the Second Battle of Ypres and the resulting gains made by the Germans, including the Bellewaerde Ridge and Hooge Chateau, the British were at a distinct disadvantage in this sector. The Tommies had been expelled from the redoubt that they’d been constructing in Hooge, and the Germans enjoyed a commanding view over the British line, and beyond, to Ypres itself, and it was considered vital that they were driven out.

Above: Hooge Chateau (Image: ww1cemeteries.com).

A surprise attack was planned involving a mineshaft being driven under the German line terminating in a chamber packed with ammonal. The 4th Middlesex Regiment was tasked with taking and holding the position following the blowing of the mine. There was no preparatory barrage in order that the Germans were caught unawares. On 19 July 1915, the 175th Tunnelling Company of the Royal Engineers detonated the mine, producing a crater measuring 120ft across and 20ft deep just north of the Menin Road. It worked perfectly, the 4th Middlesex rushed the crater and drove the German troops out, including the trenches immediately on either side, reinforcing the north and east-facing lip of the crater with sandbags. The Germans responded furiously, shelling the crater intensely, but the British held on doggedly. However, it was only a matter of time before a full-blown counter-attack came.

Above: Hooge Crater photographed in 1915 (Image: pinterest.com).

On the night of 29 July 1915, 2nd Lieutenant G. V. Carey of A Company, 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade (RB), had a strong sense of foreboding as his relief marched up to take over the line at Hooge:

I remember having a strong presentiment as I plodded up to the line that night that I should never come back from it alive (In the event I was the only officer in my company to survive the next twenty-four hours) [2].

It was eerily quiet as they covered the three miles from Ypres in the dark of night, and the lack of attention from the Germans that normally took the form of shelling and sniper fire was both unusual and disquieting in equal measure, especially as they couldn’t fail to have heard the approach of the 8th RB; the steady, rhythmic, tread of their boots accompanied by the clatter of rifles announcing their arrival. Once the relief had taken place and the 8th RB had made themselves comfortable, Carey ordered one of his bombers to lob a hand grenade into the German trenches. It exploded satisfactorily. When no response came, he ordered two more to be sent over, still nothing. Carey states: There was something sinister about this. It was now about half an hour before dawn and the order for the usual morning ‘stand-to’ came through from the Company Commander [3]. Carey worked his way along his section of the line, from right to left, ensuring that the men were ready with swords fixed (Rifles’ regiments traditionally refer to their bayonets as swords). As he reached the end of his sector:

There was a sudden hissing sound, and a bright crimson glare over the crater turned the whole scene red. As I looked I saw three or four distinct jets of flame, like a line of powerful fire hoses spraying fire instead of water, shoot across my fire-trench. For some moments I was utterly unable to think. Then there was a terrific explosion and almost immediately afterwards one of my men with blood running down his face stumbled into me coming from the direction of the crater. Then every noise under heaven broke out! There were trench mortars and bombs in our front trench, machine guns firing, shrapnel falling over the communication trenches and over the open ground between us and the support line in Zouave Wood and high explosive shells all round the wood itself [4].

It was as if the fires of hell had been unleashed. The Germans had chosen this occasion to deploy the flamethrower, or flammenwerfer; it was the first time that they’d been used against British troops. The great jets of liquid flame that were shot across the crater had momentarily created an inferno. These were real shock and awe tactics that had the Tommies reeling, there followed a hellish bombardment of all types of shell and ordnance, creating an indescribable noise, and the British were forced to relinquish the crater.

Above: The flammenwerfer in action (Image: The Daily Telegraph).

The 8th RB’s War Diary entry for 30 July 1915 read as follows:

At about 3:15am the Germans attacked. It had already been reported that they were very active in front and the whole front line was ‘standing to’ as usual at that hour. Part of the front trenches was subjected to an intense bombardment which lasted only about two or three minutes, then suddenly sheets of flame broke out all along the front and clouds of thick, black smoke. The Germans had turned on liquid fire, from hoses apparently, which had been established just in front during the night. Under cover of the flames, swarms of bombers appeared on the parapet and in rear of the line. The mass of them had broken through at the crater and then swung left and right. The fighting became very confused and the machine guns were soon all out of action. The extreme right and left hand platoons of the front line of the Battalion repulsed all attempts to bomb them out as they had not been affected by the flames; however the Germans had pushed through the whole centre in spite of most gallant fighting by officers and men and they (the Germans) were established with machine guns in the ruins of Hooge on the S. of the Menin Road commanding all the ground between there and Zouave Wood. At about between 4:00am and 5:00am B Coy counter-attacked but were beaten back by machine gun fire but established itself temporarily halfway along Old Bond Street and covered the withdrawal of Lt. McAfee and a few remnants left of two platoons of A Coy. When this counter-attack failed, the officer commanding in G10 who was then almost surrounded, fought his way back due W. along the road to the culvert. Nearly all the platoon in G4 on the right were overwhelmed and the Germans established themselves along the whole of my front and were at once strongly reinforced by the machine guns and rifles. They then attempted to bomb down the two communication trenches Old Bond Street and The Strand but these were blocked about halfway up and held throughout the day. From the beginning of the action, Zouave Wood had been subjected to violent artillery bombardment and all communication was difficult and telephones were cut. Reinforcements meanwhile had arrived from the Brigade in the shape of one Coy of the KRRC, which got up about 9:00am. The remains of the Battalion held the northern edge of the Zouave Wood.

Eventually, inevitably, another counter-attack was ordered, however as far as the 8th RB was concerned it was now a battalion in name only, such were the casualties suffered that they mustered barely a company. Brigadier-General Nugent had strongly resisted the proposal of a counter-attack, but was overruled. Knowing the futility of such a move, and with a heavy heart, he reluctantly ordered the attack against his better judgement. He later wrote:

The utilisation in the forefront of a spent battalion, that, on top of the heavy fatigue of a relief, had been fighting throughout the remainder of the night, had obtained no rest, and had been without food and water since coming into the line was, to speak mildly, a serious error of judgement – for the quality of dash, so essential in such an operation, could hardly fail to be lacking [5].

Above: The author as tour guide: Paul Blumsom speaking at Hooge Crater, September 2022 (Photos: Stephen Mulford).

The War Diary continued:

About 12 (noon) the order was received from the G.O.C for a counter attack to take place at 2:45 PM after the artillery had bombed for ¼ hour. The Battalion was to lead the attack on the left with its right on the STRAND and left on BOND STREET. The objective of the attack were G8 and G9 on the MENIN ROAD. Only one organised Coy remained in hand i.e. D Coy. C Coy was non-existent, B + A Coys had suffered heavy losses. The O.C. Battn. Gave the following verbal orders to Capt. Sheepshanks firstly that he was to attack on a front of two platoons, with two platoons in support. His right was to rest on the Strand that a bombing attack was to be made by him up the Strand at the same time. That he was to move into his position during the bombardment and get beyond our own wire, which protected the Northern edge of ZOUAVE WOOD. He was not to hope to get touch with the Coy on his left as the frontage allotted was too big, but he was to keep touch with the 7th Btn K.R.R.C on his right. The remains of A + B Coys were given practically the same verbal orders and told to attack G9 with their centre on Old Bond Street and bombers up the communication trench itself.

At 2:45 PM exactly the counter attack started, D Coy on the right advanced as if on parade. The enemies’ machine guns + rifle fire had apparently not been in any way silenced by the bombardment. The whole ground was absolutely swept by bullets. The attack was brought to a complete standstill halfway towards its objective and no reinforcements could reach it. The same thing happened on the left up Old Bond Street. The second counter-attack had failed.

The counter-attack was doomed to failure, many were mowed down by machine-gun fire, and what remained of the battalion was duly relieved and retired that night to their billets to lick their wounds. The War Diary concludes:

The remnants of the Battalion held on to the communication trench till dark + the front line of ZOUAVE WOOD was gradually taken over, first by the 7th Rifle Bde and then by the D.C.L.I. At 2:00am that morning the Battalion was taken out of action and had suffered the following casualties: - 6 officers killed, 3 officers missing almost certainly killed, 10 officers wounded. Other ranks 80 killed, 267 wounded and 132 missing, most of whom were believed to be killed, in addition to five O.R. suffering from shock.

Four machine guns out of five were lost (disabled by the enemy's fire).

The men fought without rations on water throughout the day [6].

Above: Hooge Crater Cemetery, the fourth largest CWGC cemetery in Belgium, after Tyne Cot, Lijssenthoek and Poelcappelle. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, the large stone-faced circle at the entrance to the cemetery mirrors the crater,out of shot on the other side of the Menin Road (Image: Flickr).

Two of the survivors of that fateful day were Rifleman Frederick Hamilton and Lieutenant Charles Ralph Le Blanc Smith, soldiers from opposite ends of the social spectrum, thrown together by war to fight alongside each other as brothers in arms.

Corporal 19748 Frederick Hamilton DCM, 41st Machine Gun Company, formerly Rifleman S/7625 of the 8th Rifle Brigade.

Frederick was born in Stockport, Lancashire, in 1893 to Frederick Hamilton (senior), a print worker, and Mary Ann (née Keeley). By the time of the 1901 census, the family was living at 25 Athol Street, Stockport, with Frederick’s older sister Isabella, aged 17, employed as a bobbin winder. Ten years on, the 1911 census shows the whole family – apart from Frederick senior who is listed as a letterpress printer – employed in the cotton mills, and living at 33 Penny Lane, Stockport.

Frederick, aged 18, was employed as a cop packer. He worked at R. Greg & Co., Albert Mill, Reddish, Stockport. Cop packing was a specialised job in the cotton mills; the role involved expertly winding the cops (bobbins) with spun cotton yarn whilst ensuring that the moisture content was correct preparatory to the weaving process. Many cop packers responded to the call to arms upon the outbreak of hostilities, causing a shortage of labour in the cotton mills. Frederick was one of these, and duly enlisted at Ashton-under-Lyne and subsequently posted to the 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade.

The 8th Rifle Brigade was a ‘new army’ service battalion of Kitchener men originally raised at Winchester on 21 August 1914. They embarked for France, and Frederick landed at Boulogne on 19 May 1915. They were soon deployed in the Ypres salient.

On the day in question, 30 July 1915, Frederick, in common with his fellows of the 8th RB, had a torrid time, but he rose to the occasion magnificently, distinguishing himself with his courage and coolness under fire. So much so, he was originally recommended for the Victoria Cross for his actions that day, although subsequently remitted to the award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). He was a trailblazer, the first of Kitchener’s new army to be honoured with the DCM.

Above: Artist’s impression of Rifleman Frederick Hamilton at Hooge Crater.

The citation read:

"For conspicuous gallantry and ability on 30 July 1915 at Hooge. When his own machine gun had been knocked out he mounted another, the detachment of which had been disabled, and fired it at the enemy, attacking from the rear. When the water failed, he filled the water jacket of the gun from the men's water bottles, kept the gun in action and finally stopped an enemy’s bombing attack with his fire."

The following day, he wrote to his wife Ethel:

Dear Ethel

I received your letter this morning and I thank the Lord that I am alive to read it. I will tell you about Friday, the one day we had in the firing line; dear me, it makes me shudder to think about it but I will try to tell you the thing that happened that day.

We had been in the support trenches seven days when on Thursday afternoon we had orders to pack up and get ready to move into the firing line. We got ready but it was nine o'clock at night before we moved off and we were told that we were going into the firing line for ten days. We arrived in the firing line about one o'clock Friday morning and relieved the 7th Rifle Brigade and the 8th King’s Royal Rifles. For a little while we were busy unpacking and getting guns ready for firing, then between two and three o'clock there appeared just in front of our trenches a large fire of yellow flames and a dense cloud of smoke.

We were perplexed for the moment wondering what game the Germans were up to and then they started shelling us and sending liquid fire into our trenches.

Dear, Dear, Dear, what a terrible moment that was, we got the guns firing on them when a shout went up that the Germans were advancing and that one of our platoons were retreating, we saw then that the Germans were coming and we let them have it for all we were worth with the machine guns. Suddenly one of the men on one gun rushed up and shouted that his gun was blown up and also his men but we could do nothing, only stick to our guns and keep firing and all the while they were spraying the trenches with this liquid fire. Then our gun got blown up and out of seven men on the gun, only two of us never got hit.

Well it was no use stopping there now, the gun was blown up, so I started moving down the trench with the others and it was horrible to see the dead and wounded in the trench being trampled on. I got a tidy way down the trench when I come across a machine gun turned over and the men dead under it. I looked round and saw two of our machine gun men and going to them, I said 'come on lads, let us get this gun and have a pop at the b……s. We got the gun off its tripod and put it on top of the trench, telling them to get some ammunition. I got behind the gun and simply slaughtered the Germans that were advancing and between us we killed between two and three hundred of the devils. At last they got in one part of the trench and killed a great many of our men by throwing bombs.

About the same time as they got in the trench, our gun got blown up and three men got killed by the same shell, so we retreated and then came a duel between our bombers and theirs and what a sight, it was awful, terrible and then came a calm and we could get no further.

All this took place till about eleven o'clock and out of a battalion of men, we had about two hundred and fifty left, that makes our loss over seven hundred men and all in nine hours. After that, I with a few more men went to help the 7th K.R.R.'s and in the same afternoon we had a charge and I saw men go mad with the shock of the shells.

I cannot write any more, but we got relieved at night and went back to the rest camp. We have lost all our officers besides those men and we will have a long rest now.

I lost everything, Rifle, haversack, valise and every damn thing that had been sent me.

I will close now with love to all

I remain, Yours, Lovingly

Fred XXXXX

P.S. Please show this letter to my mother and Bella because I cannot write about the horrible thing again.

Frederick’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Charles Le Blanc Smith of the Machine Gun Section, 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, wrote a fulsome letter to Frederick’s mother singing her son’s praises.

Dear Mrs Hamilton,

I expect you have already heard of all the wonderful things that your son did during the awful attack we had at Hooge and he fired one of the machine guns over the back of the trench, killing a tremendous number of Germans - at one time there were Germans in the trench on each side of him, only being kept off by one of our bombing parties. How any of them got clear, I cannot imagine; but he did and I am very pleased to say that he is the first man in the battalion to receive the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which he most nobly deserves.

I must say I am most awfully proud of the way the machine gun section behaved; they really did most exceptionally well, especially as most of those round were cowed by the awfulness of the liquid fire.

Your son is so modest; he never says anything about himself and it is all the nicer therefore, to feel that he will now go through life with one of the most coveted things in the world - a medal for outstanding bravery.

Frederick’s prowess with the machine gun earned him a transfer to the 41st Machine Gun Company. The 41st MGC eventually took part in the Battle of the Somme, and it was whilst serving there that Frederick died of wounds on 20 September 1916. He is buried at Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, Mericourt-L’Abbe, where the 36th Casualty Clearing Station had been established in April 1916.

Above: Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, Mericourt-L’Abbe, Frederick’s resting place (Image: ww1cemeteries.com).

Frederick’s obituary appeared in a local newspaper on 20 October 1916:

HAMILTON of Stockport (Died of Wounds). News has been received that Lance-Corporal Frederick Hamilton, Machine Gun Corp, died of wounds on the 20th September 1916. He enlisted in December, 1914, in the Rifle Brigade, and was awarded the D.C.M. for conspicuous bravery in France under the following circumstances: “During the attack at Hooge he fired one of the machine guns over the back of the trench, killing many Germans. At one time there were Germans in the trench, on each side of him, only being kept off by bombing parties". His officer, writing home, said: [the aforementioned letter from Lt. Le Blanc Smith appears here verbatim].Later Lance Corporal Hamilton was hit in action, and died of wounds as stated. Several days later Mrs Hamilton had a letter from his officer, who had heard that he was wounded, and asking -"How is he going on? Your husband was the very life and soul of the section, and there was none more gallant than he." Before enlisting Lance-Corporal Hamilton, who was 24 years of age, was employed at Messrs Greg’s, Albert Mill, South Reddish. He leaves a widow, who resides at 52, Freemantle Street, Edgeley, Stockport [7].

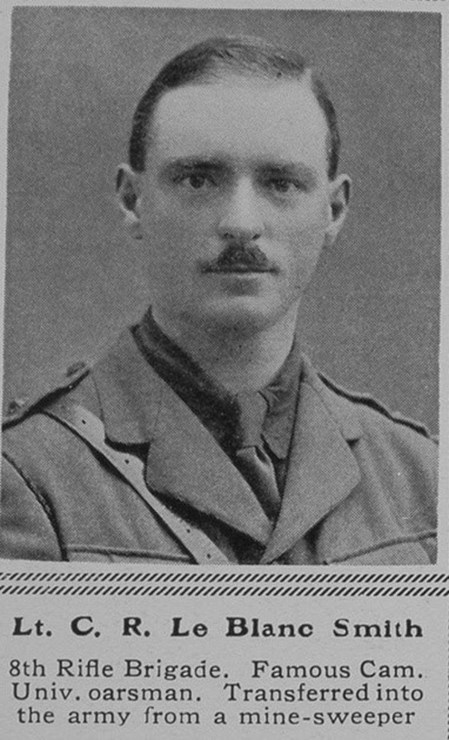

Lieutenant Charles Ralph Le Blanc Smith, 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade.

Charles Ralph Le Blanc-Smith was born in Paddington, London, on 3 March 1890, to Herbert and Gertrude Mary Beatrice Le Blanc-Smith, and baptised on the 04/05/1890 at St Mary’s Church, Standon, Hertfordshire. The family lived at Standon Lordship, a grand country house dating back to 1546 that sits on the west bank of the River Rib. Herbert was very well-to-do, having made his fortune on the Stock Exchange.

Charles had a privileged upbringing, attending Eton and completing his education at Trinity College Cambridge. A keen sportsman, he rowed for the Eton eight in 1908 and 1909 and held the record in the pairs (with E. E. Lloyd) in 1909. He went on to excel at Cambridge; he was a crewmember of the winning coxless fours in 1910, 1911 and 1912, as well as rowing for the Cambridge eight. In 1912 and 1913 he won the Colquhoun sculls and the Magdalen pairs (with C. E. V. Buxton) respectively. He was president of the Cambridge University Boat Club in 1912-13.

Above: Charles Ralph Le Blanc-Smith (Image: roll-of-honour.org).

His fledgling military career included spells as a cadet officer with the Eton Officers’ Training Corps and he commanded the Cambridge RFA in 1912, which was also when he took his degree in the autumn. Charles went on to follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming a member of the Stock Exchange. When war broke out, Charles enlisted with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 19 August 1914 as a Leading Seaman, and had been heavily involved in raising subscriptions and recruiting volunteers for a Cambridge University Hospital Ship. Briefly he served on the HMS Zarepha, earmarked for minesweeping operations in the North Sea, but realised his seven years military training with the OTC and the RFA would serve him better in the army and he managed to obtain a discharge on 10 September 1914; his RNVR record states the reason as ‘Shore to take up commission in the army’. He secured a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 8th RB and, along with Frederick, disembarked in France on 19 May 1915.

Above: Lieutenant Charles Ralph Le Blanc-Smith, 8th Rifle Brigade (Image: ww1photos.com).

On the day of the flammenwerfer attack, Charles was seriously wounded, and was out of action for nearly a month. The Battalion War Diary entry for 25 August 1915 records his return to duty: ’2 Lt. Le Blanc Smith, MG officer (wounded) returned to duty’ [8]. In August 1915, now a full Lieutenant, Charles was appointed Machine Gun Officer of the 41st Brigade (Rifles) of the 14th Division. It was whilst serving in this role that he met his end on a cold and frosty day, the 27 November 1915. He was shot by a sniper, having volunteered to reconnoitre potential machine gun emplacements at Turco Farm, an advanced position on the Ypres salient. His men, under the cover of darkness, brought his body back and he was buried the following day, the War Diary records that the interment was attended by the GOC and his staff [9].

Above: Charles’s headstone, Essex Farm CWGC Cemetery (Photo: Paul Blumsom).

His fellow officers and the machine gunners under his command formed an impromptu guard of honour. His own commanding officers – the General, Colonel, and Major – all paid tribute to him, but perhaps the most telling is that paid by his sergeant: “The loss that the whole machine gun [company] have suffered by losing him, is one that can never be replaced, a cheery word, a helping hand and one who was most respected in the whole battalion, although only a non-commissioned officer myself, I feel I have lost my brother, he was so good & kind to me & us all."

But for the war, men like Charles would not have had the intense, intimate, contact with these manual workers, labourers and artisans that they did. The sons of the upper-middle classes, of the landed gentry, of the aristocracy even, were living cheek by jowl with the working man for the first, and possibly only time, in their lives. In some cases, for four long years. These relationships could take different forms. Straight out of public school or Oxbridge, many were younger than the men they commanded. The most inexperienced of these junior officers would be taken under the wing of a seasoned working class NCO, who would teach them the dark arts of trench warfare: a crash course in becoming a soldier, and a man. Those older and more mature subalterns would take a fatherly interest in their men, especially those still in their teens, going to great lengths to ensure their welfare; effectively in loco parentis.

Many of these relationships, friendships even, continued after the war. As one of Siegfried Sassoon’s biographers observes: ‘Many middle-class, public-school-educated young men who had served as officers carried forward their concern for the servicemen they had commanded into peacetime’ [10]. Sassoon himself kept in touch with his batman, John Law, an ex-miner from south Wales, coming to his aid financially on a number of occasions in the twenties [11]. Sassoon’s fellow officer, the poet and writer Robert Graves, mentored Private Frank Richards, a stalwart of the regiment, throughout the latter’s successful post-war writing career [12].

And so it might have been for Corporal Hamilton and Lieutenant Le Blanc Smith, if their lives hadn’t been so cruelly cut short. The cop packer from the dark satanic mills of the industrial north, and the stockbroker from leafy Hertfordshire in the Home Counties. Perhaps somewhere, out there on the western front, between Flanders and Picardy, Frederick and Charles meet still, their spirit selves enjoying the camaraderie and mutual respect forged, literally, in the fire of war.

Above: The author speaking at Charles’s graveside, Essex Farm CWGC Cemetery, September 2022 (Photo: Stephen Mulford).

Article by Paul Blumsom

References

- Hitchcock, F. C., Captain, Stand To: A Diary of the Trenches 1915-1918, Naval and Military Press, Uckfield, 2009, p.66.

- Macdonald, Lyn, 1915: The Death of Innocence, Headline Book Publishing, London, 1993, p.421.

- Macdonald, p.422.

- Macdonald, p.422.

- Macdonald, p.425.

- WO/95/1895/1/2 War Diary 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, 28/05/1915 to 28/09/1915, The National Archives.

- Alderley and Wilmslow Advertiser dated Friday 20th October 1916, p.2.

- WO/95/1895/1/2 War Diary 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, 28/05/1915 to 28/09/1915, The National Archives.

- WO/95/1895/1/3 War Diary 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, 29/09/1915 to 21/12/1915, The National Archives.

- Stuart Roberts, John, Siegfried Sassoon: 1886-1967, Metro Publishing Limited, London, 2005, p.137.

- Moorcroft Wilson, Jean, Siegfried Sassoon: The Journey from the Trenches, A Biography 1918-1967, Duckworth, London, 2003, p.35

- Moorcroft Wilson, Jean, Robert Graves: From Great War Poet to Good-bye to All That (1895-1929), Bloomsbury, London, 2018, p.8.