The Disappearing Gunner

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Disappearing Gunner

There are, of course, thousands of men who were killed in the Great War who have no known grave. It is quite frequently the case these men went ‘over the top’ and were killed, then buried and their graves lost. It is however less likely that graves were ‘lost’ once men entered the casualty evacuation chain.

But the 8 August 1918 was no ordinary day, however, as it marked the launch of an offensive near Amiens, spearheaded by the Canadians. With no preliminary bombardment, the attack came as a complete surprise to the Germans, with the Canadian Corps, flanked by the Australians, quickly gaining several miles of ground. The German Chief of Staff Ludendorff would later call it ‘der schwarze tag’ of the German Army – ‘the black day’.

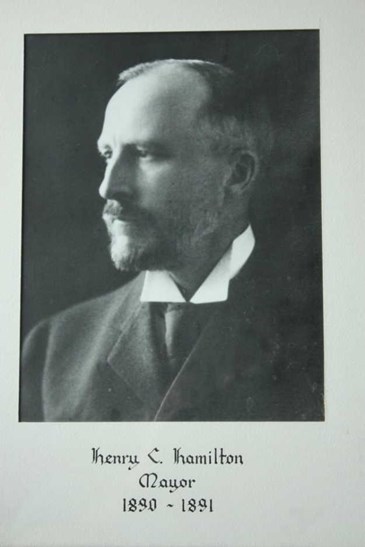

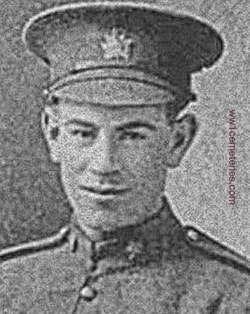

Robert Hector Hamilton was born on 26 August 1898 in Sault Ste Marie in Ontario, the son of Henry Coulthard Hamilton, a barrister and former Mayor of Sault Ste. Marie. His uncle was Major H. S Hamilton. He attended the Upper Canadian College before embarking on a career as clerk in the Imperial Bank of Canada. He enlisted on 5 February 1916 in Toronto.

Above: Robert Hector Hamilton. Photo: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Above: a newspaper report on Gunner Hamilton’s disappearance in the Toronto Star, March 1919

Robert arrived in England in November 1916. In March 1917, he proceeded to France, attached to the 1st C.D.A.C. Later that year, he transferred to the 8th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery. On 8 August 1918, Robert was in the 24th Battery - the date on which the Battle of Amiens commenced - but was wounded by a shell, which killed several men, before the commencement of the barrage at 4.20am, with the War Diary naming 5 men of the 24th Battery killed in action [1], and Corporal W. H. Morell and 14 other ranks being wounded. It also noted that Cpl Morell died of wounds at the Field Ambulance.

Walter Horace Morell was born in New Brunswick in October 1892, the son of Walter and Annie Morell. A carpenter to trade, and married to Hazel, he enlisted in April 1916.

Above: Corporal Walter Horace Morell. Photo – findagrave.com

Walter and Robert were wounded by the same shell–Walter’s service record indicates a shell wound to the head and back. It was subsequently established that Robert Hamilton has also suffered a head wound. Both men were immediately attended by the Brigade Medical officer who accompanied both men to an Advanced Dressing Station at Domart and left them there with a Cpl Dowsley. From that point, the fate of Robert Hamilton was shrouded in mystery, with the Canadian military authorities later declaring him as ‘missing’.

Above: An advanced dressing station during the First World War, where the wounded received emergency treatment. [National Library of Scotland reference: Acc.3155/Phot.C.1522]

Over the next few years, Robert’s father would carry out extensive investigations and correspondence with the Imperial War Graves Commission, The Red Cross, the Canadian Military and Canadian Medical Forces, to seek to determine the fate of his son.His search would involve the exhumation for identification purposes of over 50 graves and would also uncover a case where a soldier with a named grave had in fact survived the war.

Above: Henry Coulthard Hamilton, Robert’s father. Photo - Ancestry

The first communication from Henry Hamilton, written in December 1918, in the CWGC file [2] sets out the investigation that he had carried out and concludes that in his view “the weight of evidence appears to be that Gunner Hamilton is still living”[3] but this appears to be a conclusion solely based on there being no firm evidence regarding a grave. A much later letter in the file suggests that Henry Hamilton was “haunted by the idea that there is a bare possibility that his son is alive and might be found somewhere, possibly the victim of an aphasia”. [4]

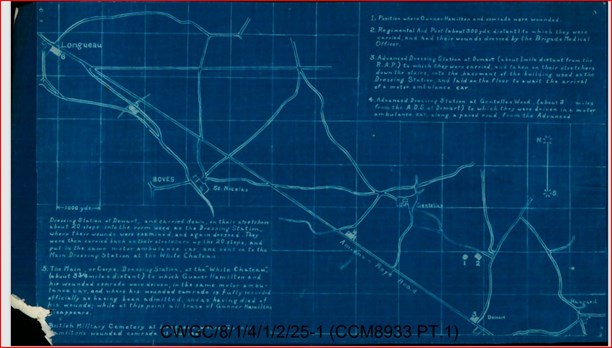

The family’s investigations involved contact with the Canadian Field Ambulance and various hospitals as it was felt that Robert may have been moved from Domart. Through these, Henry Hamilton believed that two casualties were removed from Domart to the next A.D.S. in Gentelles Wood and then moved to a main Dressing Station at White Chateau between Boves and Longueau. He later provided a hand drawn map setting out what he saw as the key stages in Robert’s journey.

Above: the map and notes provided by Henry Hamilton to the Commission – CWGC files

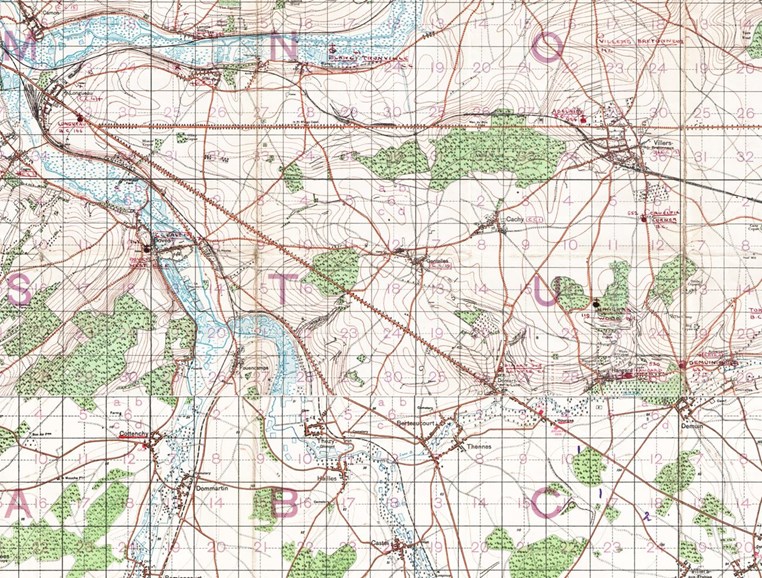

Above: Map from Mapping the Front showing the location of cemeteries and Dressing Stations in the area.

The Initial investigations

As no trace of Robert’s burial was found, Mr Hamilton’s attention moved to burials of any unidentified soldiers from Dressing Stations and Casualty Clearing Stations in the area or hospitals around the date of his disappearance.

In June 1919, correspondence in the file indicates that a lead was being pursued in Rouen. On 15 August 1918, an unidentified soldier had died and was buried in St. Sever Cemetery in the town. Henry Hamilton, although in ‘delicate health’ was in London and had made arrangements with the Canadian Forces to attend an exhumation of this body in a bid to identify whether it was his son. The exhumation was duly carried out on 12 July 1919 but with no positive identification being possible.

Above: St Sever Cemetery in Rouen. Photo –ww1cemeteries.com

By December 1919, Henry Hamilton had identified potential Casualty Clearing Stations or hospitals to which his son may have been evacuated from Domart or Gentelles Wood and then sought information on details of any unidentified Canadians buried from these. In early 1920, it appeared that there might be the potential for a breakthrough in the enquiry when it was confirmed that an unknown Canadian soldier, admitted to No. 47 C.C.S. has been buried in Crouy Cemetery. Furthermore, a photograph of the soldier had been taken, leading to the statement by the Director General of the G.R.E. that “It is probable that this Unknown Soldier is Gnr Hamilton”. [5]

Further information would flow in from Henry Hamilton in the early months of 1920, with an enquiry about the grave of a Canadian soldier who, incredibly, had been found to be alive after the war. Private Clinton Gillis was named on a grave marker in the cemetery known as Hospital Military Cemetery in Dury (the British Military Cemetery, Amiens).

Interest in this possibility was heightened by statements made by Clinton Gillis that a Canadian soldier who looked like the man in the photograph referred to above had died in the next bed to him. By August 1920, an exhumation was carried out, but it was not believed that this grave held the remains of Robert Hamilton. This would seem to be reinforced by the detail in Private Gillis’ service record which suggests that he was unconscious for three weeks after he sustained injuries on 8 August 1918. However, the grave marker was changed to indicate that an ‘Unknown British Soldier’ was buried there.

In November 1920, a further exhumation for identification purposes would follow at Mont Huon Cemetery, Le Treport where an unidentified Canadian soldier had died in hospital on 9 August 1918. Once more, this was deemed not to be Robert Hamilton.

Above: Mont Huon Cemetery, Le Treport. Photo - CWGC

In July 1921 Henry Hamilton requested that an unidentified man exhumed from Bois des Gentelles Cemetery and reburied in Bouchoir New British Cemetery be exhumed for identification purposes. The Commission agreed to this request as it was the only likely ‘unknown’ grave in the vicinity of where Robert Hamilton had last been seen and there had been some suggestion made that this was a grave of a man who had been in the 24th Battery of the CEF. Henry Hamilton’s nephew, who had sailed from Canada to England, attended the exhumation but the body was not deemed to be that of Robert Hamilton.

Above: Bouchoir New British Cemetery. Photo - CWGC

A later request was made for the exhumation of an Unknown British Soldier buried in Demuin British Cemetery. Whilst all communications between the Commission and Mr Hamilton had hitherto and continued to be conducted with the utmost politeness, notes in the Commission’s files suggest that by this point, there was some exasperation with the continuing requests for exhumations with one file note indicating “I suppose if enough graves are opened we might light on his [son’s] body?” [6]

A continuing focus on Longueau British Cemetery

1921 commenced with further requests for exhumations arising from Henry Hamilton’s enquiries. The first of these involved the grave of Cpl Walter Horace Morell, buried in Longueau Military Cemetery who had been wounded at the same time as Robert Hamilton, and who died on 8 August 1918 at No 1 Field Ambulance. Based on information from the Chaplains who were on duty at that time, Henry Hamilton believed that there may be some doubt about those buried in two graves at this time. By this time, Henry Hamilton had engaged the services of a Revd Henry Cooper, from the Folkestone Congregational Church who also requested the exhumation of Cpl Morell’s grave.

Henry Hamilton however was obviously still conducting enquiries and continued to seek information from the Commission on unidentified Canadian burials in a number of cemeteries, but it appeared that the Commission’s patience was wearing thin. Permission to exhume the grave of Cpl Morell was refused but later correspondence in 1924 indicates that an exhumation had indeed been carried out in 1921, although unauthorised by the Commission, and that the man buried in that grave had a head wound [7], although there is no record of the exhumation report in the Commission’s files. The presence of a head wound was an important point for Henry Hamilton as he believed that Cpl Morell was not wounded in the head, whereas his son had been.

A further letter from Henry Hamilton was sent in March 1921 which indicates that his view that, if his son had died, then there were only two possibilities – the first was that he was buried in the name of another man or, more unlikely, that in a frenzy of delirium, he had eluded his custodians and subsequently died in a secluded spot where his remains had not been found. [8]

By the end of 1921, Henry Hamilton’s attention turned to burials of Germans at Longueau British Cemetery, querying the numbering of rows and graves. In July 1922, he wrote once more to the Commission to argue that it was possible that his son had been buried as an unknown German, particularly as he had ascertained that a German soldier wounded in the forehead had arrived at the Main Dressing Station at the White Chateau for No 1. Canadian Field Ambulance. This letter was shortly followed up by a further communication from him indicating that his nephew had again sailed for England with the intention of attending these exhumations.

Above: from an article in a Canadian Newspaper in March 1922.

The refusal of the Commission to authorise further exhumations prompted a long letter from Henry Hamilton at the end of August 1922, fully setting out his arguments for these, strongly arguing that both his son and Cpl Morell had reached the main Dressing Station at White Chateau and as burials of those who died at White Chateau were made in Longueau Cemetery, his son may have been buried as one of the unidentified Germans buried in the cemetery. [9] His letter clearly swayed the Commission who then sought authority for the exhumation of 9 unknown German graves in Longueau British Cemetery. Although Henry Hamilton was informed that his attendance was not necessary, in September 1922 he cabled the Commission to indicate that he would attend. The exhumations were carried out in 1922, as a letter from Henry Hamilton in July 1923 indicates that two of the graves exhumed were found to be graves of British soldiers. This fact led Mr Hamilton to request the exhumation of all German graves in Longueau British Cemetery (there were 39 in total). These further exhumations were finally scheduled to take place in January 1924, with the German bodies being removed from the cemetery. No trace of any body that may have been Robert Hector Hamilton was found.

Above: Longueau British Cemetery. Photo – ww1cemeteries.com

By July 1924, Henry Hamilton was pressing the Commission for further exhumations to be carried out in Longueau British Cemetery, again focusing on Cpl W.H. Morell’s grave and those of the other graves in the same row. The rationale for this request was set out in a 15 page letter [10]and largely focused on anomalies in the Dressing Station’s record keeping and information that Henry had obtained from the Chaplain who carried out the burials of the men in that particular row of graves.

Once again, the detail and clarity of Henry Hamilton’s arguments swayed the Commission and a further 11 exhumations were carried out on 13 August 1924. None of the bodies examined were considered to be Robert Hamilton. [10]

Nonetheless, Henry Hamilton and Revd Cooper continued to focus on the grave of Cpl W.H. Morell in Longueau Cemetery in correspondence throughout 1925.

Above: the headstone for Corporal Walter Horace Morell in Longueau British Cemetery. Photo – findagrave.com

Robert Hamilton’s father, Henry Hamilton, died on 7 November 1925.

Above: the obituary for Henry Hamilton which appeared in ‘The Globe, Toronto’ on 9 November 1925. Photo - Ancestry

Following his death, his widow continued to press for the re-opening of the grave of Cpl Morell. In January 1926, the Commission agreed to the request. Fora number of reasons, the re-opening of the grave did not take place until 14 October 1926 but failed to identify Robert Hamilton.

Another possibility?

A further twist in the search for Gunner Hamilton came in September 1924 in a report prepared by one of the Commission’s staff. This identified that there were three burials carried out on 8 August 1918 which could not be traced. One of these was of an unidentified Canadian noted as having suffered a head wound. The two named men were Ptes Charles William Hackshaw and Frederick Robert Maitland, both of whom are stated to have died at No 8 Canadian Field Ambulance on 8 August 1918.

The Burial report indicated that these were buried in Domart Military Cemetery although there was not a cemetery of this name in the vicinity. However it was thought that this might refer to Hourges Orchard Cemetery, situated about 2,000 yards from the Domart A.D.S. The report also noted that burials in this cemetery appeared somewhat irregular and that “…there would seem no doubt that Hourges Cemetery does in fact contain more bodies than is shewn by the Certified Report…”[11] In addition, a special cross had been erected as ‘buried in this cemetery actual grave unknown’ for a Pte A. Walker of the 116th Canadians who also died on 8 August 1918.

Above: Private Albert Walker. Photo – ww1cemeteries.com

The information regarding Hourges Orchard cemetery was viewed as a fresh line of enquirybut the question was posed as to whether it should be taken any further at this point or await Henry Hamilton raising it. In the event, it was not raised with Henry Hamilton.

By the end of December 1924, a report indicated that it was not thought possible that there were unrecorded burials in this cemetery. Additionally, the map reference given for Domart Military Cemetery was also searched with no results. Also, there were no reports of concentrations from that location. It was also thought that the unknown burial may have been PteGeorge Williams of the 16th Battalion but the evidence for this was insufficient, and Pte Williams is also commemorated on the Vimy Memorial.

The end point

Despite all the efforts of Robert Hamilton’s family and the Commission, the mystery of what happened to Gunner Hamilton remains to this day, with his name recorded on the Vimy Memorial in France. The burials of both named men (Hackshaw and Maitland) thought to have been buried in Hourges Orchard Cemetery were also to remain untraced and they are also commemorated on the Vimy Memorial.

Above: the Vimy Memorial in France. Photo - CWGC

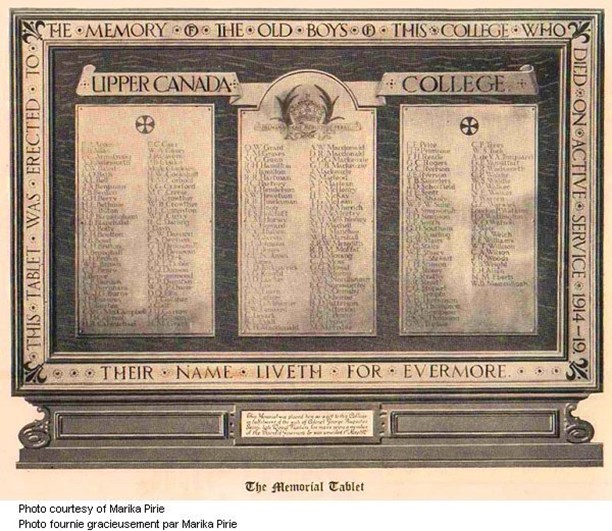

Robert is also commemorated on the Upper Canada College War Memorial

Article contributed by Jill Stewart, Hon. Secretary, The Western Front Association

References:

[1]These were Gnr Hunt, W.; Gnr Hogg, I.W.; Gnr McCabe, E.F.; Gnr Olsen, O. and Saddler Sapsworth, T.J. Of these, Gnr Hunt’s, Hogg’s and Saddler Sapsworth’s graves were concentrated to Caix New British Cemetery. Gnr Olsen and McCabe’s graves were concentrated to Bouchoir New British Cemetery.

[2] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933

[3] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 1 page 5

[4] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 2 - 2nd part page 4

[5] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 1 page 86

[6] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 1 page 364

[7] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 2 page 98

[8] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 1 page 246

[9] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 1 page 394 -400

[10] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 2 pages 95 -109

[11] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 2 page 163-165

[12] CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/25-1 File CCM 8933 Pt 2 - 2nd part page 23