The 'Engineering' Scottish Rugby international

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The 'Engineering' Scottish Rugby international

George Lamond is one of the many thousands of officers who lost their lives in the Great War. Before his war service, he had excelled at sport (being a Scottish Rugby international) and also been heavily involved in raising the height of the original Aswan ('Low') Dam in Egypt. This engineering skill meant he was - during the war - involved in much important work in Mesopotamia.

George Alexander Walker Lamond was born on 23 July 1878 at 6 Rosslyn Terrace, Kelvinside, the fourth son of Robert Peel Lamond, and his wife Isabella Jaap.

Above: George Alexander Walker Lamond

The other children of Robert and Isabella were Robert Jnr., Henry, John M., Douglas, Isabella M.G., Camilla M., Jane W., and Catherine W.

The family lived at Rosslyn Terrace for some years, at least until 1891, but in 1901 the family were at Marchmont Terrace, although while most of the children were in residence, George was abroad. Robert Peel Lamond died on 20 November 1909.

George was educated at Kelvinside Academy, which was founded the year he was born.

Above: Kelvinside Academy

His education was completed at Glasgow University where he studied to become a Civil Engineer and he then served an apprenticeship with Formans and McCall. This firm was based at 160 Hope Street in Glasgow and specialised in Railway Engineering but also built some architectural bridges.

George then took a position with the firm of Sir John Aird. This was a business respected internationally for the huge projects it undertook, and which included the Tilbury, Royal Albert, East and West India Docks in London and the Manchester Ship Canal. The firm also handled major projects in Denmark, Russia, France, Italy and Brazil. The most challenging and memorable ongoing project was in Egypt damming the River Nile at Assuan when John Aird & Co was the main contractor. John Aird himself acted as engineer with Sir Benjamin Baker working to the design of Sir William Willcocks and the firm contracted to complete the huge project in 5 years being paid £76,648. Every 6 months for 30 years. This was a huge opportunity for any engineer, and for George, in his 20s it was the chance of a lifetime. Preliminary operations were commenced at the site of the dam in April, 1898, and in the early summer of 1899 the number of men employed on the undertaking reached a total of 13,000. This first dam was finished in 1902. The dam was 2,200 yards long, with 180 sluice-gates, and its maximum height from the foundation is about 130 feet. The total amount of granite masonry its construction involved was about 1 million tons. The work altered the Nile above Assuan into an immense reservoir, which, when full, held about 38,000 million cubic feet of water. The Assiut Barrage was carried out at the same time.

Above and below: Construction work on the Nile

George’s sporting ability had become evident when he was in his teens, and he played for the Kelvinside Academicals team at the age of 16. He played centre three-quarter in inter-city matches and in Glasgow City team against the Rest of Scotland team in 1896, playing throughout the following few years. His skill was recognised and in 1899 he was chosen to play for his country, earning his first International Cap in the team playing Wales.

Scotland Team 4 March 1899. (Scotland 21, Wales 10). G.A.W.Lamond is on the right of the front row

He was known for his ability to drop-kick with either foot when running at speed, for making openings and then feeding players on his wings. His second cap came with the match with England the same year, but his international career was halted when he left the country to work in Egypt.

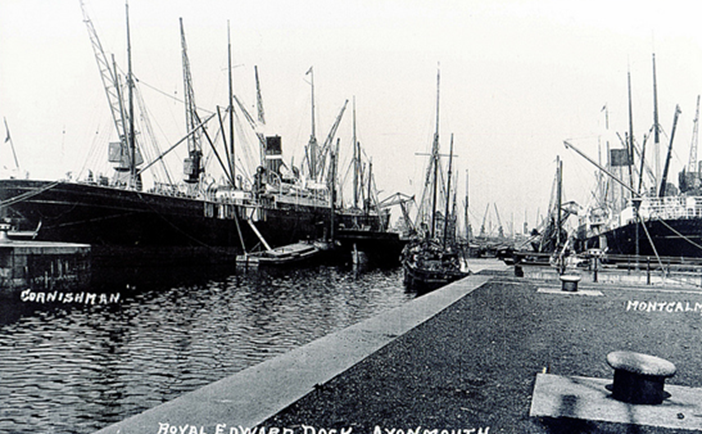

George returned from Egypt in 1902, and was sent to Avonmouth, where work on the Royal Edward Dock was to start during March. The Prince of Wales cut the first sod, The works at Avonmouth were to increase the deep-water area of the port by 30 acres, and reclaim from the sea a large tract of land at the same time tipping the excavated material onto the mud slopes of the Severn, raising them above sea level. The complex was opened by his Edward VII in 1908.

Royal Edward Dock, Avonmouth

During his time in the West Country, George was quick to join the local Bristol City Rugby Club, and he played three-quarters for the team for three years. He was Captain of the team and also of the Gloucestershire County Team, The teams played against all the leading Welsh teams. George also played for the Anglo-Scots against the South of Scotland, for the Cities against the Rest of Scotland, as he had in 1896, and he gained his third Scottish Cap in 1905 when after a poor season, Scotland defeated England at Richmond. This was to be the last match as he returned to Egypt and retired from the game. It was clear that George loved sport and was not only a good tennis player but was good enough at golf to take part in the heats for the Amateur Golf Championship at St. Andrews. Fishing was another of the outdoor pursuits he enjoyed, and his brothers envied his ability with a fishing rod.

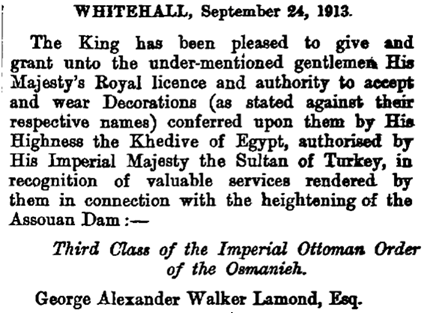

The next stage of the work on the Nile was to iron out some ongoing problems by the heightening of Assuan and the completion of a barrage at Esneh and the Menufieh Regulator and George was sent to work on the project. He must have played a major role as he was decorated with the Orders of Medjidieh and Osmanieh by the Khedive of Egypt and the Sultan of Turkey.

He was only able to manage a few visits home, but in 1912 he married Jean Cavan Leishman, and of course managed to play a few games of rugby.

When war broke out in 1914 George returned home, and was put to work by the Government at Salisbury Plain. He was then given a commission in the Royal Engineers and sent to the Western Front, where he was involved in the strenuous efforts made by the Engineers.

The Inland Water Transport and Docks Section of the Royal Engineers were originally formed in December of 1914 to deal with and to develop transport on canals and waterways of France and Belgium. The Section operated under the Director of Railways, but, owing to the rapid development of Inland Water Transport, a special directorate was formed in October of 1915. In the summer of 1916 all non-transport work in Mesopotamia became a responsibility of the I.W.T and during 1917 this was extended to work in Egypt, Salonika, and other theatres of war. The shortage of adequate and dependable water transport was affecting the military effort in the area, (such as the relief of Kut) due to the difficulty of getting men and equipment to the area they was needed. While there is familiarity with the Western Front the struggle against the Turkish Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) is relatively obscure. Then, even more than today, control of the country depended on keeping the twin great rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates open. So successful were they that, by the end of the war, the river system, backed up by railways, was taking nearly 3,000 tons a day in a fleet of 2,000 craft up to 500 miles upriver from the port of Basra - then as now the main British base in the region. As a result of this miracle of organisation, the enemy was driven from Kut to Baghdad to Mosul.

The extended responsibilities of I.W.T. entailed large increases in establishments. Up to December of 1917, some 1,100 officers and nearly 30,000 men transferred to or enlisted in the Inland Water Transport Section. During 1917 over 465 officers and 1,394 men were drafted to Mesopotamia. The European personnel were supplemented by over 42,000 native personnel from India, Egypt, West Africa and China.

On arrival in Mesopotamia the I.W.T. formed its own construction department and George was in charge of the construction and organisation of the new port and works from September 1916. His promotions had been rapid, but not unexpected. He was well qualified and had extensive experience both in the construction of ports and railway engineering, as well as experience working in the Middle East. He was sent to Mesopotamia with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Above: Work on a slipway at Basra

Plans on a very large scale were made to extend and improve the facility to enable repair work to vessels. The area was extended to 40 acres, there were new wharves and jetties and to facilitate the work specialist machinery was sent from England. Associated with these extensions were new workshops and buildings, a boat yard, building shed, hospital, post office, ration store, cookhouse, dining room, and other buildings. The dockyard was quite self-contained. George was mentioned in despatches by Sir Stanley Maud.

Mesopotamia was notorious as an unhealthy area, and working beside water often meant catching a fever. George unfortunately became very ill after succumbing and was sent to the Hospital in Columbo (Sri Lanka) to recover. His condition unfortunately worsened and he suffered an attack of Pneumonia, and as he was already very weak his body was unable to recover, and he died there on 25 February 1918. George Alexander Walker Lamond was buried at the Colombo (Kanatte) General Cemetery (see below).

Like most men who went to war, George had prepared for the eventuality of being killed, and had drawn up a will. His moveable Estate amounted to £652.19.8.

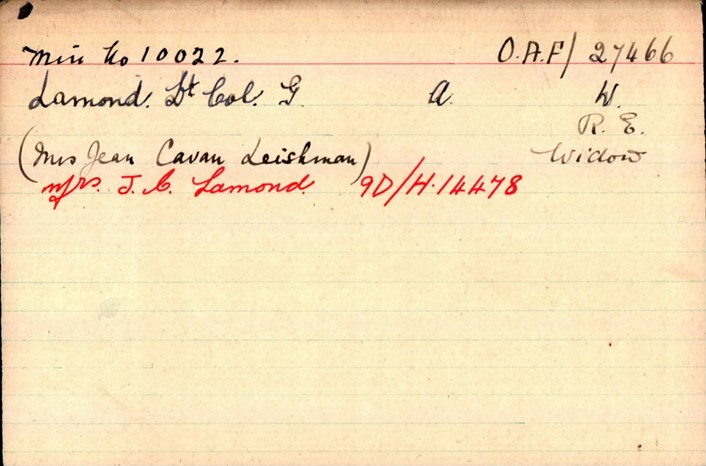

There was also a pension claim, the evidence of this being shown in the WFA's Pension Record archive

Above: The Pension Record Card which has recently been made available via the WFA's access to Fold3.

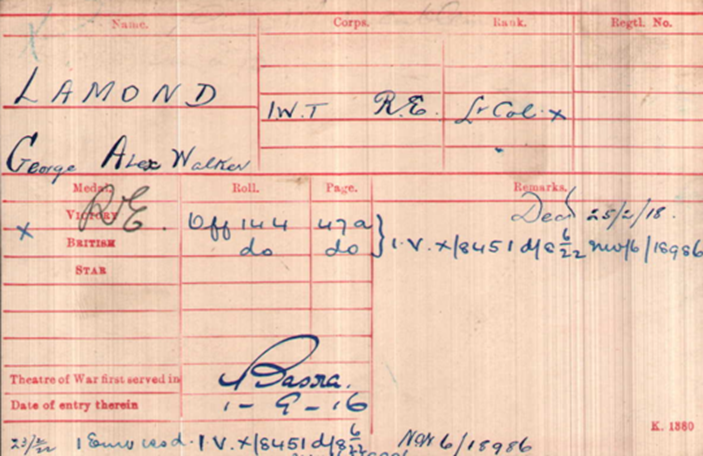

Above: The Medal Index Card, again from the WFA's archive.

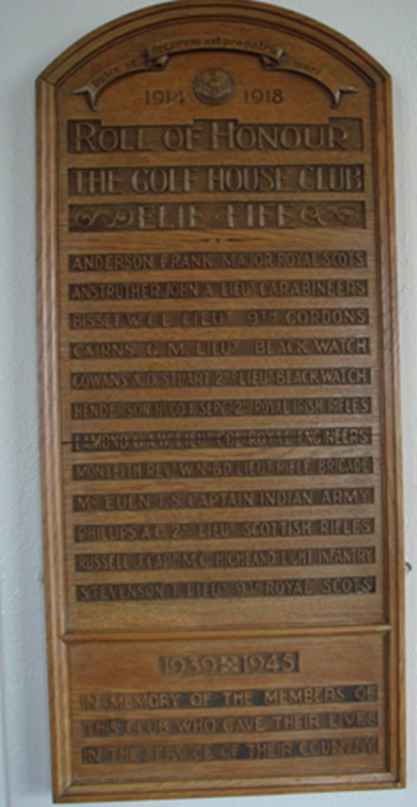

As well as his place on the Kilmun War Memorial, George Alexander Walker Lamond is remembered at Kelvinside Academy and at the Golf Club House at Elie in Fife.

In 1918 George’s wife Jean was living in Dowanhill, at 28 Highburgh Road but shortly afterwards was living at Hopehill in Kilmun.

In Old Cathcart Cemetery is the family plot. George’s name appears on the gravestone, with his parents and two of his brothers

Robert Peel Lamond B Oct 28th 1841 D Nov 20th 1909.

Wife, Isabella Jaap B April 10th 1846 D Oct 1st 1921.

Charles Ernest B Aug 25th 1880 D Oct 16th 1881.

Robert Jan 31st 1868 -Jan 31st 1931

George Alexander Walker Lt Col R.E. B July 23rd 1878 Died at Colombo (on sick leave from Mesopotamia) Feb 25th 1918

Article by Ann Galliard

Further resources:

The Inland water transport in Mesopotamia (takes you to an external website)