The Heilsberg 39: A New British First World War Cemetery in Poland

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Heilsberg 39: A New British First World War Cemetery in Poland

Between August and December 1918 a number of British Prisoners of War died at Heilsberg Prisoner of War camp in the east of Germany. It is likely their deaths were a result of insufficient food, overwork or one of the diseases that often swept through these overcrowded and insanitary camps. Conditions in Germany at this time were harsh. Food was scarce due to the blockade enforced by the Royal Navy, with the German Army and Navy having priority above the civil population, which suffered from the effects of malnutrition. Inevitably, rations for prisoners came even lower down the list of priorities for the German authorities.

Heilsberg was one of the Mannschaftslager, these were the soldiers' (as opposed to officers') camps. Normally these comprised wooden barracks about 150 feet in length (each housing 250 POWs), although it is believed that in Heilsberg camp the barrack blocks were partly underground to preserve heat. Most prisoners were required to work, despite the insufficient rations. The Heilsberg camp contained mainly Russian and Rumanian prisoners, with British and Commonwealth POWs only a small proportion of the camp population. (It is believed that in October 1918, there were about 1,000 British POWs at the camp at its satellite or sub-camps, out of a total of 95000 prisoners).

Food parcels were sent to the camps by relatives and groups (such as the Red Cross) from the UK and commonwealth. These food parcels were not only good for morale, but were probably instrumental in saving many prisoners from starvation. The contents of these parcels often included tea, condensed milk, jam, dried fruit, meat and cheese, as well as cigarettes and pipe tobacco.

Image: Great War Red Cross Poster. Source Wikipedia

Letters from home! Who can imagine what it meant to us? For fifteen weary months we had been forced by starvation and hardship to submit to humiliation and indignities, allowed barely sufficient food to keep body and soul together, and forced to gather weeds and herbs for sustenance; gaunt, unwashed, unshaven and devoured by vermin; knowing practically nothing of what was going on beyond our barbed wire enclosures; seemingly dead to the world, and, for all we knew, mourned as dead; would we ever see our loved ones again?

...And at last to see the old familiar handwriting; to be brought into touch with the outer world. At sight of those letters I broke down completely.

Tommy Taylor (captured 1917), Heilsberg prisoner-of-war camp (courtesy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Australia).

One of the British prisoners was 19 year old Frank Bower from the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Frank had been born in Huddersfield on 30 March 1899 to John and Mary Ellen Bower. His parents lived at 54 New Street, Paddock, his father working on the railway. In the following years, the family moved from Paddock to Ravensthorpe, taking up residence at 4 Netherfield Road.

Image: Netherfield Road, Ravensthorpe. Frank lived in the middle house (courtesy author's collection).

Until he joined the army on 13 April 1917, Frank worked as a clerk in the goods department of the London and North West Railway Company in Dewsbury. He also attended Dewsbury Technical School. Like so many of his generation, Frank attended the Parish Church: St. Saviour's Church was just around the corner from his home.

IMAGE: Frank Bower

After joining the army, he had a prolonged period of training (partly due to the policy of not sending soldiers to France until they were 19 years old) - he was eventually posted overseas just after his 19th birthday in April 1918, joining the 22nd Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers, which was in the Houplines sector, near Armentieres.

Supposedly a quiet part of the front, this state of affairs was about to change as the Germans launched a massive onslaught on the British lines on 9 April. The fighting here became known as the Battle of the Lys. Frank was destined to see no fighting. He was admitted to hospital (possibly a casualty clearing station) on 9 April, suffering from a poisoned stomach. He was taken prisoner, probably when the casualty clearing station was over-run.

Although his parents had received a letter from him dated 6 April 1918, saying he was in the trenches, the next they heard was a report stating that he was missing "...as between April 11th and April 14th".

Image: British and Portuguese POWs, probably captured during the Battle of the Lys, April 1918. Source German Bundesarchiv

A further letter came to them on 4 May from one of Frank's comrades, giving them the news that Frank had been in hospital at the time of the German offensive. Desperate for information, they wrote to both this correspondent and to his commanding officer, but without receiving any reply. It was not until early June that they received a field postcard from him to say that he had been made a prisoner and he was at Limburg on the Lahn in Germany. Although no doubt worried about their son, Frank's parents were no doubt relieved that he was alive, and would have been confident that he would eventually return home. Unfortunately this was not to be the case.

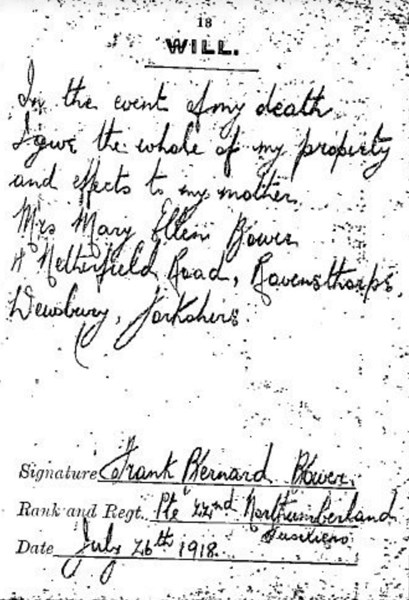

In July Frank completed the will in his Army pay book, leaving everything to his mother.

In mid-October Frank's parents received a letter from him (he was now at Friedrichsfeld) to say that he was 'in the pink' (ie in good health). He went on to say that amongst the soldiers in his hut was George Hargreaves of 25 Back North Road, Ravensthorpe and Harry Gibson of 17 Anroyd Street, Westborough, Dewsbury. It is possible that this was his last letter home.

Sometime between writing this letter and the end of October, Frank was moved from Friedrichsfeld to Heilsberg Prisoner of War camp, about 80 miles east of the city of Dantzig (now Gdansk). It was here that on Tuesday 29 October, Private Frank Bernard Bower died, aged just 19.

Image: The burial of a POW at Schweidnitz POW camp. Image courtesy of the BBC.

Frank was buried at Heilsberg Prisoner of War Cemetery in Germany (the region was ceded to Poland after the Second World War; Heilsberg became Lidzbark Warminski). The cemetery contained several thousand burials, mainly of Russians and other eastern Europeans who had died as prisoners of war. The number of British prisoners (39) was a very small proportion of the total burials, which were made in a series of mass graves.

Image: Lidzbark Warminski Camp Cemetery. This contains over 2800 war graves. Nearly 2100 are of Russian POWs, there are also 500 Romanians, with other nationalities (British, French, Belgian, Italian and Serbs) making up less than 200 of the burials. Courtesy Wikipedia

The Imperial War Graves Commission (as it then was) realised in the 1930's that the 39 British burials could not be located amongst the mass graves. However, the men were commemorated on the site. This situation continued until the 1960's when it became apparent that the cemetery could no longer be adequately maintained. As part of the Commission's policy of ensuring all soldiers are commemorated, the 39 men were named on a small memorial at Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery (75 miles away, to the west).

Image: the Memorial at Malbork which, from the 1960s, was how the 39 were commemorated.

New Project

Recently, as a result of improved accessibility and maintenance at the cemetery, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has sought and obtained approval from local authorities for a project to erect 39 headstones to commemorate the casualties buried within the Heilsberg / Lidzbark Warminski cemetery. Official clearance to proceed was received in August 2013 and work on the project commenced shortly after.

The 39 headstones are grouped in a special memorial plot, in the vicinity of a marker stone, known as a Duhallow Block (so called because the first such memorials were erected in Duhallow A.D.S. Cemetery, near Ypres in Belgium.) The block has been engraved with the inscription seen below:

THE MEN IN WHOSE MEMORY THE HEADSTONES IN THIS GROUP HAVE BEEN ERECTED DIED IN CAPTIVITY DURING THE 1914-1919 WAR AND ARE BURIED ELSEWHERE IN THIS CEMETERY

The headstones are numbered 1 – 39 and have been assigned to each casualty in alphabetical order. The new Lidzbark Warminski War Cemetery (located here) was completed in 2014 and an inauguration ceremony took place on Friday, 16 May 2014.

Image: The entrance to the Lidzbark Warminski cemetery.

David Tattersfield

WFA Development Trustee

Further reading:

British Prisoner of War Deaths - a case study from one PoW camp