'In the event of my death': An analysis of what can be gleaned from soldiers wills

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'In the event of my death': An analysis of what can be gleaned from soldiers wills

During 2013, David Tattersfield, a trustee of The Western Front Association, provided First World War historical advice to HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS), part of the Ministry of Justice. The reason for this advice being sought from the WFA relates to a project to make available online 277,450 wills of soldiers who were killed between the years 1860 and 1986. With 229,481 of these (which is over 80% of the total) from the First World War, the WFA was invited to provide assistance to HMCTS and their partners.

Although a number of wills of soldiers who were killed in the First World War have been available for some time, these have been for Scottish and Irish soldiers only. Some examples of wills of soldiers who survived the war are in circulation, but this new service allows access to the wills of English soldiers who were killed in the Great War. It is therefore a remarkable window into the past for family researchers and has the potential to provide previously unknown information which may add 'pieces to the jigsaw' for many genealogists.

The wills HMCTS has made available were written by NCOs and privates only: officers' wills are not part of this project,[1] nor are wills of men who served in the Royal Navy available. It is believed that sailors' and marines' wills were the responsibility of the Admiralty and were kept separate from soldiers' wills, which were the responsibility of the War Office. The location of the Admiralty wills is not known.

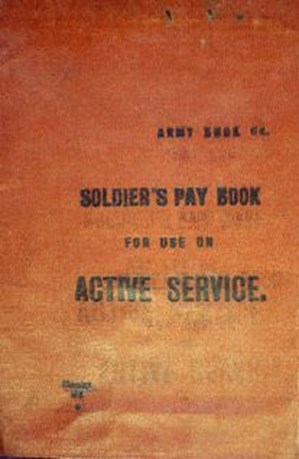

Soldier's Pay Book

On joining the army, a soldier was issued with an Army Pay Book (AB64) which had to be kept with him at all times. One of the few times he would be parted from his pay book would be if he was involved in a trench raid when all identification was removed.

The Pay Book contained details of the soldier's next of kin, some medical information as well as records of his training history. It also contained a form on which the soldier could complete his will, together with a template example to show how this should be completed.

Image: Soldier's Pay Book, AB64. Courtesy of the King's Own Museum.

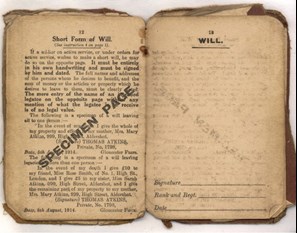

Image: Pages 12 and 13 of a Soldier's Pay Book, with instructions on how to complete the will (which in this case has not been completed). Courtesy of The Royal Anglian & Royal Lincolnshire Regimental Association, Lincoln branch.

The text of this image reads as follows:

|

If a soldier on active service, or under orders for active service, wishes to make a short will, he may do so on the opposite page. It must be entirely in his own handwriting and must be signed by him and dated. The full names and addresses of the persons whom he desires to benefit, and the sum of money and the articles of property he desires to leave to them must be clearly stated. The mere entry of the name of an intended legatee on the opposite page without any mention of what the legatee is to receive is of no legal value. The following is a specimen of a will leaving all to one person:- |

Below this template, the army provided a specimen of a will for those wishing to leave legacies to more than one person:

|

In the event of my death I give £19 to my friend, Miss Rose Smith of No 1 High Street, London and I give £5 to my sister, Miss Sarah Atkins, 999 High Street Aldershot, and I give the remaining part of my property to my mother, Mrs Mary Atkins, 999 High Street, Aldershot. (Signature) Thomas Atkins |

This 'informal' (and unwitnessed) will in a soldier's pay book was sufficient evidence of the individual's wishes to be valid in English law. A new will could be made out when a soldier was issued with a new pay book (it is not clear what the process would be if a change of beneficiary was desired prior to a new pay book being issued).

If the soldier was killed, the will would be extracted from the deceased's pay book (assuming it was found on his body) and sent back to the War Office in the UK.

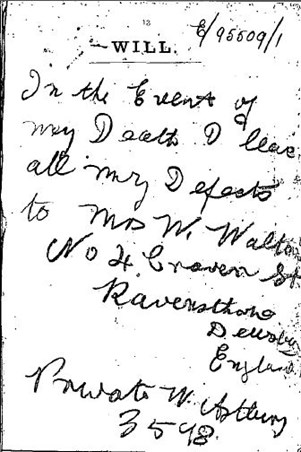

Image: The will of William Astbury who left all his "Defects" [sic] to his adoptive mother.

Image: William Astbury

The number of First World War wills that HMCTS has made available is only about 25 per cent of the total British and Commonwealth fatal casualties and this appears to be substantially less than the full number of wills that one may expect to see. However, some investigation into the numbers has indicated that this may in fact be the full set of English wills.

A statistical analysis

According to Statistics of British Military Effort,[2] Regular Army and Territorial Force other rank deaths (excluding 'Empire' and Royal Naval and Mercantile Marine fatalities) for the Great War period to November 1918 totalled 433,715.[3] It is not inconceivable that a small number of men who died in the CEF, AIF and NZEF may have had English wills, but this figure is a suitable starting point to estimate the number of English wills that should be available.

Using the same source (Statistics of British Military Effort) it appears that recruitment in England and Wales amounted to 86% of total UK recruitment.[4] Therefore (recognising that some men recruited in England and Wales may not have been domiciled in England for probate purposes) 86% of 433,715 gives us a figure of 372,995.

So why are there 'only' about 229,000 wills available out of nearly 373,000 that we may expect to see? This is a "will survival rate" of about 60 per cent. Explanations for this "will survival rate" include the likelihood that many soldiers may not actually have made out a will, despite being urged to do so, or their pay book may not have been recovered from their bodies.

A practical analysis

As a result of the invitation extended to the WFA to take part in the process, a 'road test' of the service has been undertaken, using a 'typical' war memorial – being the memorial commemorating the men of Ravensthorpe, in West Yorkshire.

Of the 113 positively identified individuals named on the Ravensthorpe war memorial, 13 were either officers, in the Navy, in other national contingents or did not go on active service.[5] Thus, usefully, there are exactly 100 men for whom a will could be available.

A search on the HMCTS web site (at the time of writing, this is still a beta site) has indicated that 40 wills of the Ravensthorpe men are available. This success rate is somewhat less than that which could have been expected in view of the statistical analysis above, but as this is a small sample, such variations may not be entirely unexpected.

Of the 60 missing Ravensthorpe wills, 32 are for men who are named on memorials to the missing and from whose bodies the pay book may never have been recovered.[6] (For some of these men it must be assumed that their bodies were so badly destroyed when they were killed that their pay book was also destroyed). This leaves just 28 men without a will on the HMCTS database who do have a known grave and for whom it could be reasonably expected there would have been a will. Of course, for these 60 missing wills, as mentioned above, some men may not have filled out the will form in their pay book at all.[7] (The issue of there not being wills for men whose bodies were not lost or destroyed is something that will be worth studying in greater depth and may be a suitable project for degree level students.)

Even though a proportion of the will forms were not completed, were destroyed or were unrecovered when the soldier was killed (or even lost on the way back from the front line), it does seem that a high proportion of wills have survived.

Given the practical difficulties in recovering the pay book and the reasons for the non-recovery mentioned above, it is fair to assume that the wills HMCTS have published constitute the entire set of English Wills that were recovered from the battlefields.

What is available?

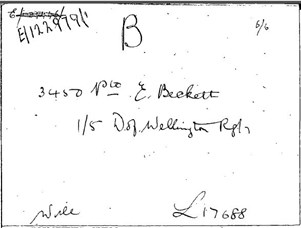

Firstly, there is a copy of the envelope in which the documents have been stored. This also contains the bar code used by the storage/scanning provider. Next comes a scan of a second (or 'inner') envelope which shows the information recorded by the clerks in the War Office.

Image: The 'Inner' envelope containing the will of Private Ernest Beckett.

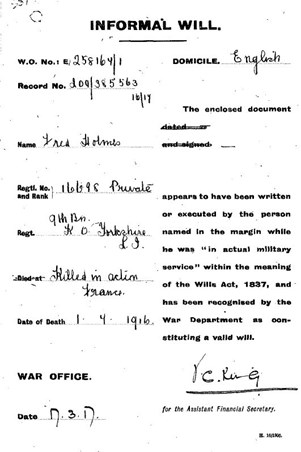

Within the inner envelope would have been two documents. The first of these is a form signed "for the Assistant Financial Secretary" stating that the enclosed document (the soldier's will) "...appears to have been written or executed by the person named [on the form]...and has been recognised by the War Department as constituting a valid will". This form would have been completed some months after the date of death of the soldier in question.

Image: The War Office's Validation Certificate relating to Fred Holmes' will. The form's official name and exact rules relating to this being issued are currently not known.

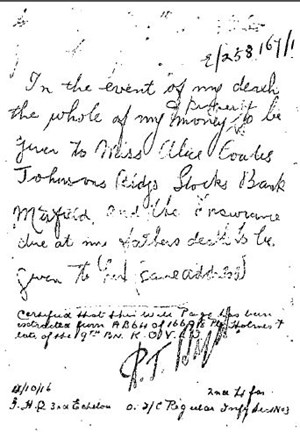

Next comes the actual will, extracted from the Army Pay book. Although many of these are based on the template suggested by the Army "I leave the whole of my property and effects to my mother" these wills do provide clues such as the level of literacy (via the quality of handwriting). They can also provide details of the soldier's unit, possibly provide a new regimental number, as well as the obvious matter of to whom he wished to leave his property.

Looking at the will of Fred Holmes (who died on 1 July 1916), had the will not been located it could be assumed (because he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial) that no trace had been found of Fred's body. The existence of the will does make the location and burial of his body immediately after his death a possibility, but – for reasons which will be discussed shortly – this will's existence does not prove that his body was recovered immediately after his death.

Image: The undated will of Fred Holmes

"In the event of my death the whole of my money (and property) to be given to Miss Alice Coates [of] Johnsons Buildings, Stocks Bank, Mirfield and the Insurance due at my father's death be given [to her ?] same address."

Image: Fred Holmes

Fred Holmes was educated at Wheelwright Grammar School in Dewsbury. Fred's father died less than a year later.

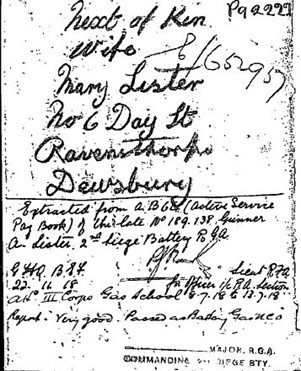

In a large number of cases, but not all, there is a final piece of paper which HMCTS provides. This is the confirmation that the will has been extracted from the particular soldier's pay book. In the case of Fred Holmes above, this (unusually) was added to the bottom of the will, but it is normally a separate document. Occasionally this confirmation provides tantalising insights, such as the example for Arthur Lister (below).

Image: Confirmation document with Arthur Lister's will

"Att[ended] III Corps Gas School 8.7.18 to 13.7.18. Report – Very good. Passed as Battery Gas NCO"

Image: Confirmation document pertaining to the will of Private John Schofield.

Evidence of Pay Book being removed from the body

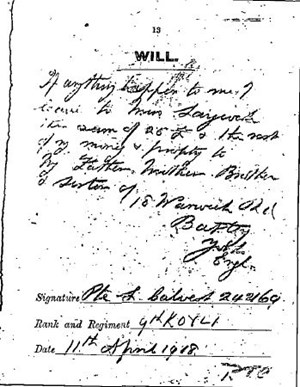

As with Fred Holmes, above, Leonard Calvert has no known grave. Leonard is therefore commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing. Having been sent to France on 1 April 1918, Leonard completed his will on 11 April (possibly the news of the German offensive prompted him to undertake this action). He was killed on 29 April during a bombardment near Mount Kemmel.

A brief article published in the Dewsbury Reporter on 25 May 1918 indicated that Leonard initially had an identified grave and that, immediately following his death, his possessions were returned home. His obituary states that Miss Laycock of Eastfield Road, Northorpe, who was Leonard's fiancée, received a letter from Private G Metcalfe. Private Metcalfe told how "...Leonard had been left out of the line to stay with the transport where he had the misfortune to be killed." He went on to say that he had helped to bury Leonard, and had "...taken possession of Leonard's pocket wallet from which I got your address and also a letter which you had sent to him. I will get his personal belongings and send them to his home as soon as I can."

It can be assumed that it was during the process of removing the personal effects from Leonard's pockets that his pay book was obtained and handed in, presumably to a company officer or the battalion adjutant. Miss Laycock is mentioned in the will and in the obituary, which is a useful confirmation of their relationship.

As mentioned above, the fact that a will has been found may be taken as evidence that the soldier's body was found after his death. With the case of Leonard Calvert, this evidence was always available via the obituary in the newspaper. Had the newspaper obituary not been available, the existence of the will dated only a few days before his date of death is overwhelming evidence of the body being recovered. However, caution needs to be exercised here. Had the will been executed a long time prior to the date of death (or as in the case of Fred Holmes above the will is undated) there remains the possibility that the will was from an earlier pay book (which was not carried by the soldier). Therefore, it cannot be definitely stated that the existence of an informal will is absolute proof of the soldier's body being located: examination of the date of the will being executed needs to be considered before making such assumptions.

Image: Leonard Calvert's will

"If anything happens to me I leave to Miss Laycock the sum of 25£ [sic] and the rest of my money and property to my Father, Mother, Brother and Sister of 18 Warwick Road, Batley, Yorks, Eng."

Image: Leonard Calvert

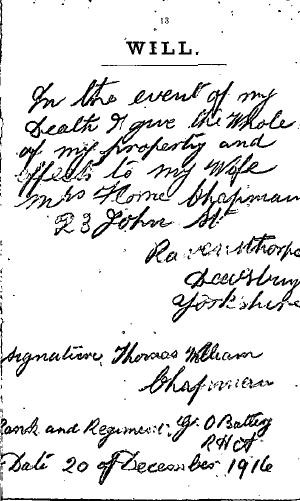

Identifying a particular unit

Useful information can be extracted from these wills in terms of a soldier's unit. In the case of Tom Chapman, the will tells us that he was with O Battery (XIV Brigade) RHA. Whilst it had always been known that he was with XIV Brigade, his battery was previously unknown. This level of extra detail is highly valuable as it enables a deeper level of research to be undertaken. It is possible that this kind of extra information will be particularly useful for artillerymen and engineers where the soldier concerned made a careful note of his unit.

Image: Thomas William Chapman's will

Image: Tom Chapman

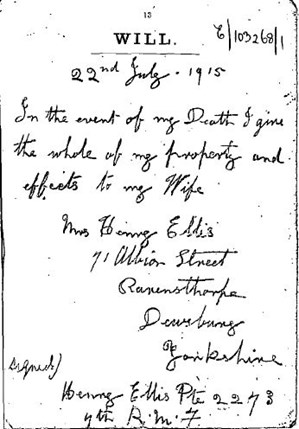

Other Theatres

The wills, not surprisingly, include men killed in other theatres of war besides France and Flanders. The example below (dated 22 July 1915) was written by Harry Ellis of the 7th Royal Munster Fusiliers just over two weeks before his unit was involved in the Suvla Bay landings at Gallipoli. It is known that Harry died from wounds on 17 August 1915 and he was buried at sea from a hospital ship. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial.

Image: The will of Henry Ellis

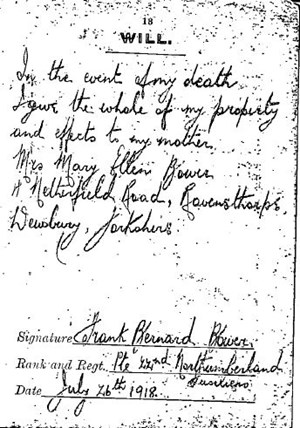

Prisoners of War

From the will of Frank Bower, we see evidence that men did not complete their wills until it was almost too late.

Frank was in hospital with a stomach ailment when the German Georgette offensive overran his CCS in April 1918. He had only just joined his battalion a few days before the attack. Taken prisoner, he wrote cheerful letters home and seemed likely to survive the war. He remained in possession of his Army Pay book and he made out his will on 26 July 1918 whilst in a PoW camp.

This also provides an example of a soldier going on active service without having completed the will in his pay book.

Image: Frank Bower

Private Frank Bower died, aged just 19, on Tuesday, 29 October 1918 and was originally buried at Heilsberg Prisoner of War Cemetery. Despite the imminent collapse of Germany, it seems that the authorities obtained his pay book and sent it to the UK, which is remarkable evidence that administrative functions still operated effectively within Germany even in the last weeks of the war.

Image: Frank Bower's will

Typed copies of Wills

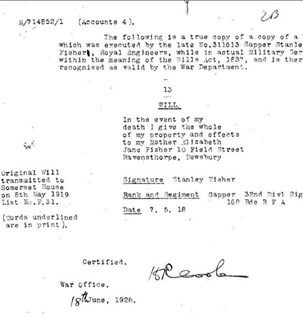

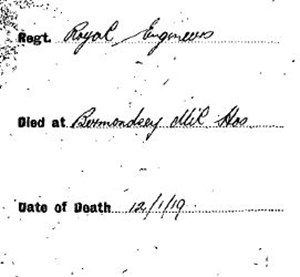

The example below, for Sapper Stanley Fisher, is a typed copy of his will rather than the original. The reason for this typed copy, rather than the original handwritten will, being provided is not known. One explanation may be to do with the fact that Stanley died of wounds in the UK in 1919. The date of the typed copy (1928) is surprisingly late. The place of his death (Bermondsey Hill Hospital) is detailed on the Validation Certificate enclosed with the will.

Image: The typed will of Stanley Fisher

Image: Stanley Fisher

Image: Extract from the Validation Certificate indicating the place of death, which could be valuable new information to genealogists.

Over-completed and under-completed wills

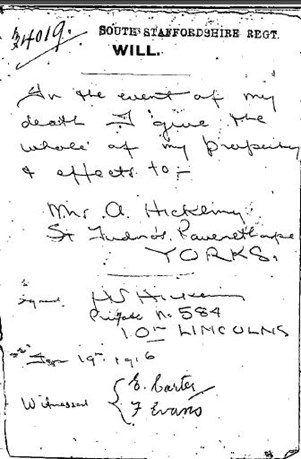

The will of Harold Vivien Hickling was unnecessarily witnessed. Hickling was a well educated man, so perhaps he believed that the will should be witnessed in accordance with non-Army / English Law. The "South Staffordshire Regiment" on the top of the will seems to have been stamped on the will when it was passed through the system back to the War Office.

Image: Harold Vivien Hickling

Image: Hickling's will

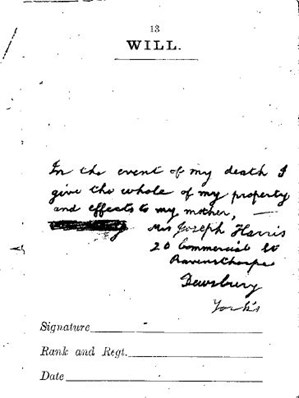

Conversely, Joe Harris, a veteran of the 1916 Battle of the Somme who was killed in September 1918, neither signed nor dated his will. It was still accepted as being valid.

Image: Joseph Harris

Image: The unsigned and undated will of Joseph Harris

Dating transfers between units

In other cases, information contained in the will can enable us to fix a soldier in a unit at a particular moment in time.

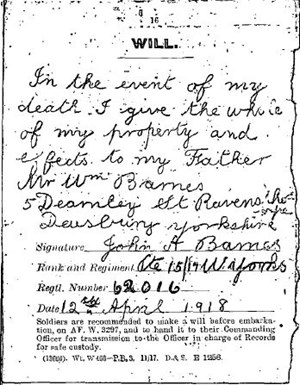

In the case of John Barnes, the timing of his transfer from the 15th/17th West Yorkshires to the 8th (Leeds Rifles) battalion of the regiment was not previously known but, from the will, we now know he was in the 15th/17th battalion on 12 April 1918. John was killed on 20 July 1918 and he is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial to the Missing so, once again, it may be assumed his body was initially located but subsequently lost.

Image: The will of John Barnes.

Image: John Barnes

Touching Bequests

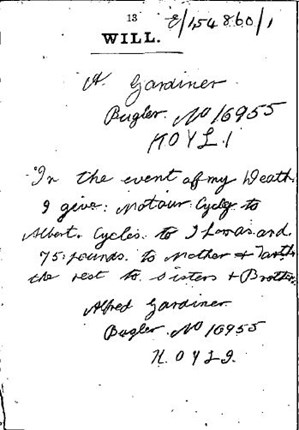

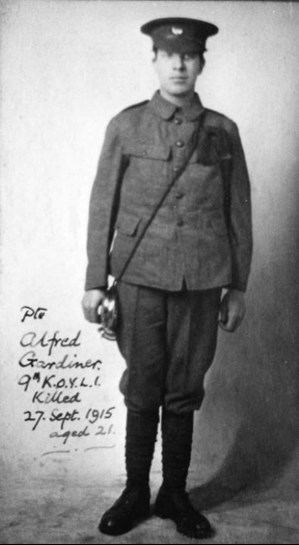

There are sometimes personal touches to the wills, such as this thoughtful bequest by Alfred Gardiner to his brothers.

Image: Alfred Gardiner's will

"In the event of my death I give: Motour [sic] cycle to Albert. Cycles to Thomas and 75 pounds to Mother and Father the rest to sisters + brothers"

Image: Alfred Gardiner

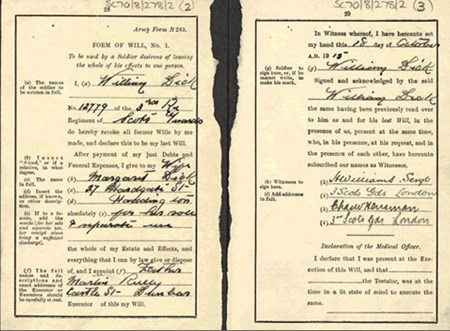

Formal Wills

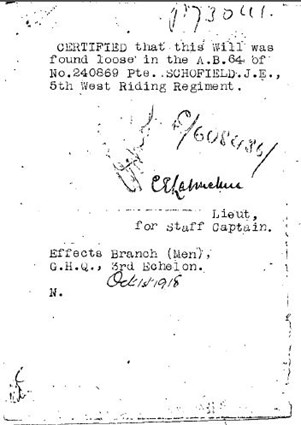

A small number of the wills are 'formal' wills, rather than the 'informal' wills so far discussed. These tended to use Army form B243 (for naming a sole beneficiary) or B244 (for more than one beneficiary). These formal wills would not be part of the soldier's pay book and would not routinely be carried by the soldier.

Image: An example of a formal (witnessed) will, written and signed by the soldier on Army Form B.243 (Image courtesy of National Archives of Scotland NAS ref SC70/8/278/2)

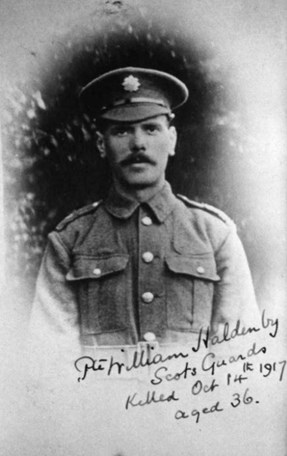

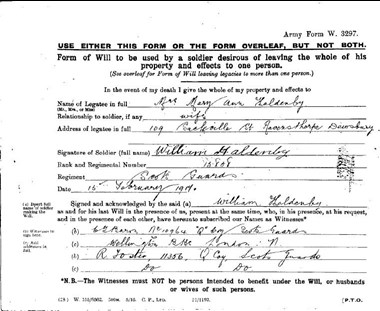

A rarer type of formal will is the one that used Army form W3297, written and signed by the soldier, for naming one or more beneficiaries. Private William Haldenby, who was killed at Third Ypres, has left us an example of this formal will using form W3297.

Image: William Haldenby

Image: William Haldenby's formal will on Form W3297.

A second example of form W3297 is provided within the sample wills examined for this article. In this case, the soldier in question completed two informal wills in December 1915 and April 1917 but also a formal will on form W3297 in March 1917. Unlike the example for William Haldenby above, in this subsequent example, the form W3297 seems to have been completed at home (as the witnesses are civilians), thus giving a degree of knowledge about the soldier's home leave

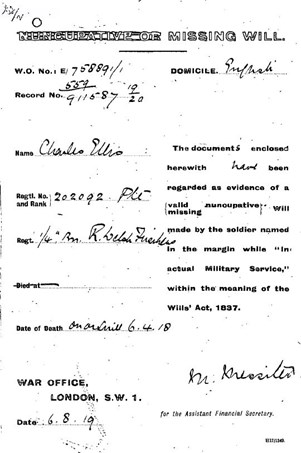

Nuncupative or Missing Wills

It would appear that if a will was missing, the War Office accepted statements obtained from a soldier's family regarding information the soldier may have stated verbally concerning his last wishes. The War Office also accepted such statements from his family if they had seen the missing will, for example the soldier may have shown his family the relevant page of his pay book with his completed will, prior to leaving for the front.

Further work needs to be undertaken on nuncupative wills which, in the sample studied, provides just two examples. There is a much smaller number than the number of "missing" wills in the sample reviewed here which suggests that this process was applied (or successfully concluded) only occasionally.

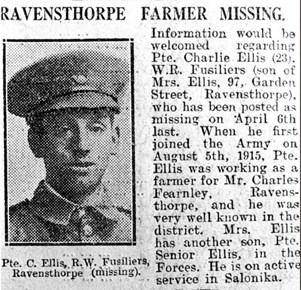

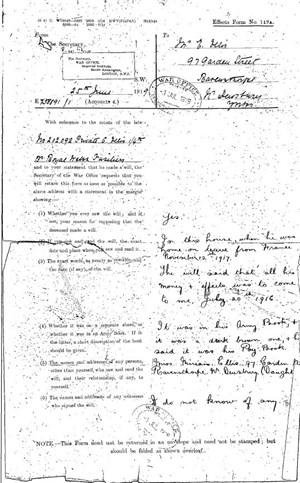

Image: Variation on the standard War Office form confirming the document enclosed is regarded as evidence of a valid missing / nuncupative will.

Image: Charles Ellis

Image: The documentation sent to Mrs Ellis using the nuncupative wills process regarding her son (who is commemorated on the Pozières Memorial to the Missing).

Testamentary Wish Letters

Letters from soldiers who expressed some form of final wish could be accepted instead of a will. These letters are occasionally found within the documents made available by HMCTS.

An example of this is the letter from Driver John Davill. The letter was dated 6 September 1914 and, in this letter, he tells of his training on the East Yorkshire coast and how he will be back 'some day'.

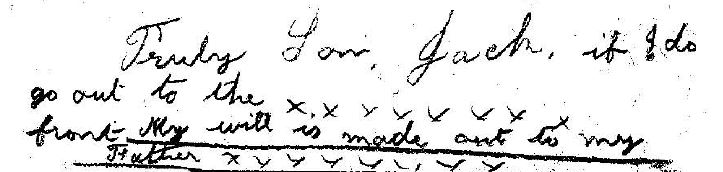

Image: The first page of John's letter dated 6 September 1914, written whilst based in Hull.

Image: John Henry Davill

Image: The last sentence of John Davill's letter which reads "....if I do go out to the front my will is made out to my father". It is likely that someone in the War Office underlined the last part of the sentence and these few words were enough for this to be considered a valid will.

The 'some day' referred to at the start of his letter never arrived, John Davill died in France less than one year after writing this letter.

HMCTS is to be applauded for making these wills available. Not only do the documents provide valuable clues for researchers, but they also provide a link to forbears and being able to see their handwriting is a tangible connection to those who we seek to remember.

© David Tattersfield, 2013

[1] Although none has turned up yet (this is a brand new service which will benefit from further study) it is possible that some wills may exist for officers who were commissioned from the ranks, as a small number of this type exist within the equivalent service provided by the National Archives of Scotland.

[2] Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-20 (London, 1922)

[3] This excludes in excess of 50,000 other post war fatalities commemorated by the CWGC.

[4] Scotland recruited 11% of the total and Ireland 3%. For Scotland, the 11% of UK recruitment represents nearly 48,000 men. The National Archives of Scotland holds "approximately 26,000 wills" for Scottish soldiers which is about 54% of the total number of men recruited, a figure not too dissimilar to the 60% survival rate of English wills. The 9,000 Irish wills which are available represents only 26% of the total number of Irishmen who made up the British Army. The reasons for this disparity are not known.

[5] Soldiers were encouraged to complete the will when they were sent on active service; it is therefore reasonable to assume that many did not consider completing the form until this juncture.

[6] However, this is not something that can be taken for granted as a proportion of the Ravensthorpe men commemorated on memorials to the missing (rather than buried in known graves) do have their wills held by HMCTS.

[7] Further analysis has shown that of the 40 wills made available, 30% are for men who are now commemorated on memorials to the missing (as opposed to over 50% of the wills being missing for those commemorated on memorials to the missing). The conclusion from this seems to be that the recovery of a soldier's body leads to a greater likelihood of there being a surviving will. Of course, the reasons for the non-survival of a pay book and will when there is a known grave are numerous; for instance, men may have been buried in haste and the pay book may not have subsequently survived when they were exhumed and buried in permanent cemeteries. Additionally, bodies recovered by Germans would probably have had identification removed for intelligence purposes.