The Infamous Dutch Lady And Other Famous Espionage Agents of the Great War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Infamous Dutch Lady And Other Famous Espionage Agents of the Great War

Arguably the two most famous, or infamous, individuals engaged in espionage during the Great War were a tall exotic dancer of Dutch/Indonesian extraction and the sender of a telegram who was a German official of the highest rank. There were others who, perhaps, we would call today 'celebrity spies'. Very little is known about the details of their espionage activities, but their involvement in the secret, and not so secret, spying world during the Great War is worth recording.

Mrs Margaretha Geertruida (M'greet) McLeod nee Zeele. [English = Margaraete Gertrude]

M'greet was born on the 7th August 1876, in Leeuwarden, in northwest Holland near the Waddenzee. She was the second child of Adam and Antje Zeele.

Adam Zeele's hat business flourished and his family lived a comfortable urban life until he began to speculate on the Dutch Stock Market. M'greet was only 13-years -old when he went bankrupt and the family had to move to more modest quarters in a less salubrious part of the town. Even then Adam did not stay around to mend the family fortunes; he left alone for Amsterdam in search of work.

Mme. Zeele took the change of circumstances hard and became depressed. When M'greet was only 15-years-old, her mother died and, as was the custom in those close-knit family days, the family was dispersed amongst the caring, and not so caring, relatives. M'greet went to her godfather's house in the town of Sneek, 20kms southwest of her birthplace where he arranged for her to be boarded at a teacher training college in Leiden. M'greet studied the teaching of kindergarten children. Unfortunately, there was also a minor scandal over her attentions to the husband of the headmistress. In the manner of these things, M'greet was shown the door. Another relative took her to live with his family in The Hague. There she led a quiet industrious family life until she read an advertisement in the Personal Columns of a popular newspaper that stated a Dutch Army officer on leave from the Dutch colonies in East '?wanted to meet a girl?object matrimony'. A meeting was arranged and the 38-year-old officer and the 18-year-old, dark-haired and olive complexioned young woman were mutually attracted. Soon after, on the 11th July 1895, Rudolf McLeod (the name came from his Scots ancestry) and M'greet were married.

A son was born on the 30th January 1897. Almost immediately, McLeod was re-posted overseas and the family left for Central Java - allegedly the home-country of M'greet's mother. M'greet quickly adopted to the local ways and outwardly enjoyed life.

McLeod did not prove to be much of a husband and father, he drank heavily, chased women and when drunk was verbally and physically abusive to all around him, including M'greet.

On the 2nd May 1898, second child was born, a daughter.

McLeod was posted to Medan in Sumatra and departed leaving M'greet and family in Java. But he soon sent for her. She immediately came into her own as the wife of the Garrison Commander. Her highly successful soirées clearly demonstrated for the first time her innate abilities as an entertainer. All this social popularity in a highly social expatriate society reflected well on her husband and he became much more amenable towards M'greet and his world.

A dreadful shock was to disrupt this new aura of harmony. Both the children were poisoned, presumably by a disgruntled servant, and the son died.

Re-posted to Java, the distraught family disintegrated in mutual recriminations and, to cut a rather sordid story short, they returned to Europe where M'greet obtained a legal separation from McLeod with the custody of her daughter. However, financial difficulties meant she soon had to return her daughter to the care of her husband. To her anguish, she never regained custody of her daughter.

Several attempts followed to get herself established in the theatrical world of Paris.

M'greet's first step was to give herself a stage name. Her first choice was the name Lady McLeod, but she soon changed it to the more exotic, and appropriate, Mata Hari; Malay for 'the sun' or 'in higher Malay 'the eye of the dawn'.

On the 15th March 1903, Mata Hari obtained an engagement at the Musée Guimet (a music hall type venue) as an exotic dancer in a sari, performing Indian Hindu type dances; a sort of Indian Gipsy Rose Lee with a fantastic invented life story to match.

An immediate success, she travelled Europe performing to rapturous audiences.

Nevertheless, at Mata Hari's first performance in Paris she was already 29 years old, a bit long in the tooth to be starting a dance career where body form was all. As time passed she worried about her future and increasingly entertained men as a courtesan to boost her income and maintain her high living standards.

One of her many admirers was a German spymaster named Traugott von Jagow.

He, it is claimed, introduced her to espionage and got her enrolled at a school for spies located in Antwerp, Belgium. Graduating from the school she was given the code number H 21.

Mata Hari left France shortly after war broke out and travelled around Europe. Finally she ended up in Paris where the anti-espionage police viewed her with some suspicion.

In Paris, she met a young officer of Russian origin, Vladimir Masloff, and they became lovers. All too soon, Masloff was called to duty and was seriously wounded. He was evacuated to a hospital at Vittel, a small town south of Nancy, France. As Vittel was located in the War Zone, Mata Hari had to get permission to travel there to visit Masloff.

Above: Mata Hari and Vladimir Masloff

This involved meeting a French Army Captain Georges Ladoux, an expert in counter espionage. She applied for travelling permission as a neutral Dutch national and a Francophile. Ladoux thought her to be excellent material for a spy for France against Germany and Mata Hari got her visit to see Masloff.

Badly in need of funds for the long-term medical care of her badly wounded lover, Mata Hari eventually agreed to spy for France. She was aiming at a 'big time, once only'; spying coup that would set her and Masloff up for life.

The 'mark' was General Moritz Ferdinand von Bissing, the German 'Overlord' of occupied Belgium.

Above: General Moritz Ferdinand von Bissing

If possible, through him she was hoping for an even bigger prize, an old 'friend' of hers, Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany.

In order to get to Belgium, Mata Hari had to take a circuitous route through Britain where she was arrested on landing, mistaken for another German spy. Mata Hari immediately quoted Major Ladoux as her guarantor and he got her freed and sent on to Spain. She arrived there highly frustrated, short of money and no nearer to either of her German targets, von Bissing and Wilhelm.

Whatever else happened next, it is known that she did ensnare another German, Major Arnold Kalle and attempted to extract from him information about German espionage plans, so she had something important to pass onto the French. Kalle, suspicious of her motives, gave her out-of-date information about German and Turkish intentions to use submarines to insert agents into French Morocco. He then waited to see if she passed it on. This she did, communicating with Ladoux in Belgium.

In return, Mata Hari gave Kalle gossip she had heard about the Allies' intention to stage new offensives and French attitudes vis à vis the Anglo-French alliance.

At their next rendezvous, Kalle passed on deliberately false information. Mata Hari relayed it to Ladoux in all expectation of having achieved the much needed coup.

Returning to France to collect her dues, she was shunned by Ladoux, who condemned her information as entirely bogus, saying he would not pay her anything until she gave him something really seriously important and reliable.

Unabashed at her obvious deficiency in the skills of espionage, Mata Hari continued to seek another star German target. Ernest Augustus, the heir to the dukedom of Cumberland in England and Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg in Germany, has been identified as her new target. But Ladoux and Co. became increasingly alarmed when her name became associated with the German agent U 21. The French now seriously considered her to be a double agent.

Coincidentally, the German espionage commanders thought the same thing, and wished to somehow get rid of Mata Hari. It probably occurred to them that matters could be arranged so the French did the dirty deed. Whether it was the German Army Intelligence or the British MI5/MI6 that set Mata Hari up is debatable, but it seems highly probable one of them informed the French about her dabbling in espionage.

By chance, in early 1917, the French espionage agency was under pressure to show some progress in dealing with German spies. Mata Hari was to hand, so they arrested her. Her interrogator was Captain Pierre Bouchardon of the French Army.

During the extended interrogation, Mata Hari was pressed to admit she was a double agent and spying for the Germans. She insisted she had only worked for the benefit of France.

She was kept in virtual isolation under very poor conditions. Only her lawyer, M. Edouard Clunet had access to her. Then in his 70's, he was her personal lawyer and a former lover; but not best professionally qualified to deal with her international espionage case.

Mata Hari's trial began at the Palais de Justice on the 24th July 1917, before a highly excited audience. The prosecution was led by Lieutenant André Mornet and the Presiding Judge was Lieutenant-Colonel Albert Ernest Somprou. It was in every sense a Military Court conducted by military officers with the rather restrictive limits of personal rights that that imposed.

Unable to cross-examine the witnesses of either side, the Defence was strictly limited as to what it could do. However, one witness, and former lover, M. Henry de Marguérie, did make a statement in Mata Hari's defence, denying emphatically that there had ever been any discussions between them on military matters.

The outcome was not hard to foresee. The judge and the six assessors unanimously condemned Mata Hari to death and fined her court costs.

One statement that Mata Hari made during her trial is often quoted as 'Harlot. Yes. But traitoress? Never!' The anticipated reprieve did not come and a decidedly ageing M'greet met her fate on the 15th October 1917.

She had not been informed of the date of her execution and it was a distraught and disbelieving prisoner who was led from her cell. However, she quickly regained her composure and faced the 12-member firing squad head high and without the customary blindfold. It is said she blew a kiss to the firing squad, but the other extraordinary gestures she is said to have made are most unlikely to be true.

The shots were lethal - to the heart - and the coup de grâce a formality.

Mata Hari awaiting death by firing squad. Almost certainly a reconstruction for the 1920 film, with Asta Nielsen in the title role

As no relatives claimed her body, it was given to a medical school for dissection.

Mata Hari was probably a victim of her own naiveté, egotism and of 'being in the wrong place at the wrong time'. That she was responsible for the deaths of thousands of Allied troops is highly unlikely. She was just a very erotic and exotic Oriental dancer who got involved with wrong men at the wrong time and, accordingly, by the way of her life and death, became the most celebrated female spy of all time.

The Zimmerman Telegram

Arthur Zimmermann, born 5th October 1864, was the German Foreign Secretary from 1916 to 1917.

Germany conducted covert communications with Mexico - an ally of the United States - with a sensational proposal that Mexico should enter an alliance with Germany against the United States during the Great War. The principle was that in return Germany would help Mexico recover territory lost to the United States in the 19th Century.

By any measure, this was espionage at the very highest level, as the United States was a self-declared neutral country at that time.

Zimmermann had realised that a resumption of unconditional submarine warfare by Germany could well incite the United States to retaliate for the sinking of United States' ships by at last intervening in the land war on the Western Front in favour of Britain and France.

The modus operandi of the Zimmermann Plan was to divert the United States away from the Western Front by forcing them to concentrate their military forces in the United States to meet a threat in the south from Mexico. An unsettling dispute was already taking place on America's southern borders with the Mexican bandit Pancho Villa.

Additionally, Germany wanted the President of Mexico to use his influence to convince the Japanese Government that an alliance with Germany would be in Japan's long-term interest and thus further unsettle the Americans.

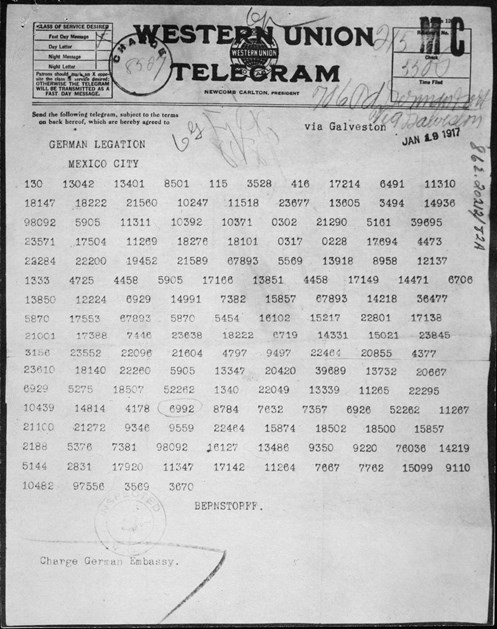

On the 16th January 1917, Zimmermann chose to communicate with the Mexican President - Venustiano Carranza - by a coded telegram. It was sent first to Ambassador Count Bernstorff at the Washington Embassy and then on to German Ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. The telegram also asked the Mexican President to act as an intermediary and to request Japan to join the alliance of Germany and Mexico. (Eventually, on the 14th April 1917, President Carranza formally declined Germany's proposals, but by then the USA was at war with Germany).

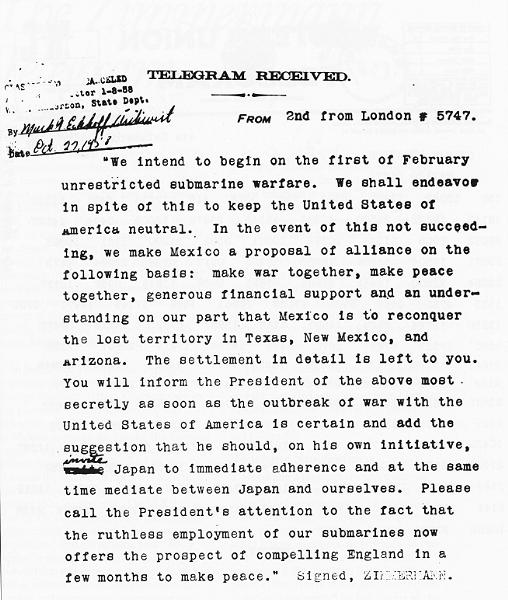

The Zimmermann Note stated '?an offer on our part that Mexico is to recover her lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona?' (i.e. 16.3 % of the land surface of then USA). 'Germany and Mexico would "Make war together, make peace together"'. The telegram also promised 'financial assistance'.

The message was sent in the German diplomatic code through three established channels. The first of these was a wireless receiving station on Long Island, New York, USA, specifically kept operational for the Germans by the U.S. The second through the Stockholm foreign ministry which, as a neutral country, routinely on-forwarded German Government official telegrams to the Americas. And the third through the American's own diplomatic cable service - one of President Wilson's 'sweeteners' to encourage German co-operation with the U.S. The telegram was perfidy exemplified.

One of three messages was intercepted by the British Admiralty Intelligence Branch - via the transatlantic link, which passed through Britain - and it was substantially decoded, but not completely. To complete the British Naval Intelligence Branch's coup, an actual word for word copy of the message was obtained from the public telegram system in Mexico, which, as the British had foreseen, would be the route the German Embassy in Washington would use to pass on messages from Berlin.

The Washington German Embassy used an old cipher code different from the one used by the German Government in Berlin to send the telegram to Washington (the German Code #0075). So the full content of the Zimmermann telegram could be revealed to the Americans without the British having to admit either to the unethical wiretapping of the American sources, or to the ability of British Intelligence to break the new German #0075 code. An incomplete, or incorrect, interpretation of the Zimmermann telegram would have indicated it was the new German code as yet not fully broken by the British.

The contents of the message were personally conveyed to President Wilson on the 24th February 1917 by the British Foreign Secretary. Arthur Balfour was chosen to present it as he was thought to be well trusted by the Americans. A very unhappy President Wilson released the contents of the Zimmermann telegram to the international press on the 1st March 1917.

Both Japan and Mexico immediately denied any complicity in the Zimmermann Plan.

On the 3rd March 1917, whilst condemning Allied wiretapping techniques - techniques which the American then strongly disproved of - Zimmermann admitted to the authenticity of the document. The British coup was complete.

Public opinion in the United States was already exercised about Germany's resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare as of the 31st January 1917, and the conflict that was raging with the Pancho Villa's Villistas in cross-border raids on the southern border with Mexico. Now, deeply worried by the ruthless activities of the German submarines, and uncertain of the mendacity of Mexico in the now authenticated Zimmermann Plan, the sentiment of the American public swung behind American participation in the war against Germany. Even in the areas where ethnic German populations were concentrated, only a minority deferred, whilst many preferred to remain silent on the issue.

On the 4th and 6th April 1917, the U.S. Senate and Congress respectively approved the intention of President Wilson to go to war against the German Government (but not the German people). The United States formally declared war on Germany and became an independent 'Associate Power' of the Allies. After much agonising and debate, Wilson had decided on his own criteria that the Allies were right and the German Government '? must be humbled and seen to be humbled'. Most importantly, Wilson foresaw America's role in the ensuing post-war Peace Conference as a dominant one. In the end, the United States was sucked into the cauldron of the Great War like all the others belligerents, and it became a fight to the finish.

The U.S. Declaration of War against Germany's Allies, Austria and Hungary only took place on the 7th December 1917.

Above and Below: The Zimmermann Telegram as coded and as de-coded

There have been many important documents in ancient and modern wars, but seldom can any single document have had more import than did the Zimmermann telegram in the Great War. It is most improbable that the Allies could have won the Great War under such favourable conditions without the intervention of the Americans that the telegram certainly expedited. And, above all, there was the potential threat that the resultant commitment of American industry and manpower posed for The Great Powers in 1919, had they not capitulated in November 1918.

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell

Not really spy in the normal sense, Gertrude Bell was a highly valued intelligence gatherer and analyst in the Great War.

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell (1868–1926) by unknown photographer, c. 1900

Born on the 14th July 1868, she was the grand daughter of a famous Iron Master and industrialist, Isaac Lothian Bell. She graduated with a First in Modern History from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford at the extraordinary young age of 19-years.

Her first foray to the Middle East came in May 1892 as a 24-year-old when she visited Iran. After that she began an almost continuous cycle of travel backed by her family's great wealth, all the while studying languages - Arabic. French, German, Italian, Persian and Turkish - as well as applying herself to archaeology.

In 1900, she travelled to Jerusalem and met the King of the Druzes, Yahya Beg. During 1905, she travelled extensively in Arabia meeting many of the tribal leaders and writing an acclaimed book entitled 'The Desert and the Sown'. By 1907, she was in Turkey where she undertook important archaeological studies and co-authored a book with Sir William Ramsey.

At the beginning of 1909, she travelled to Mesopotamia (now modern Iraq) where she instigated exciting new archaeological studies and, in the course of her work, met T. E. Lawrence, soon to be the famous 'Lawrence of Arabia'.

Gertrude Bell in 1909, visiting archaeological excavations

Back in England at the outbreak of the Great War, Bell volunteered her services to the Government for the Middle East but was refused. Disappointed but undismayed, she expended her great energies usefully. First she ran the Red Cross organisation's office in Boulogne, France and later transferred to London to dynamically run its offices there.

By the end of 1915, the Powers-That-Be finally overcame their reluctance in favour of her linguistic abilities and her almost unique knowledge of the Middle East; she was asked to join the Arab Bureau in Cairo. There she prepared dossiers on putative Arab leaders and their allies who might be prepared to join the British in their fight against the Ottoman Empire. The British Army found her reports exceedingly helpful, as did Lawrence himself later on.

This task completed Bell moved to Al Basrah on the 3rd March 1916 where she was seconded to the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force (MEF) as adviser to the Chief Political Officer, Percy Cox. Her own title was Liaison Officer, Correspondent to Cairo. Her principle job there was the production of maps that would guide the MEF advance on Baghdad. After the fall of Baghdad on 10th March 1917, Cox called her to there and appointed her to the post Oriental Secretary, which formally made her the only female Political Agent in the British Army.

Later she served in Persia (now Iran), where she was struck down by a serious attack of malaria. This effectively put her out of action until the end of the war. For her services in the Great War she was awarded the CBE and given accolades in the British Parliament.

After the War she continued to be active in Arab affairs and earned the sobriquet, 'The Uncrowned Queen of Iraq'. Gertrude Bell died in Al Basrah, aged 58, unmarried and childless, from an overdose of sleeping pills. Gertrude Bell, CBE, was not only the first female Arabist of her day, she was probably the finest Arabist of either sex.

Her eventually unproductive involvement in the post-war pursuit of the Arab Nationalist cause was indubitably a source of great disappointment to her in an otherwise highly successful academic and professional life. Perhaps, it was this failure, allied to her misfortunes in love and other family matters, that precipitated her early death.

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir, Governor General of Canada.

Born in Perth, Scotland, on the 26th August 1875, John Buchan was the son of a Scottish minister of the Free Church, and as such had a conventional upbringing. He was educated at Glasgow University and Brasenose College, Oxford making many friends whom in later years held important positions in Government and British society.

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (1875-1940), Novelist and Governor-General of Canada.

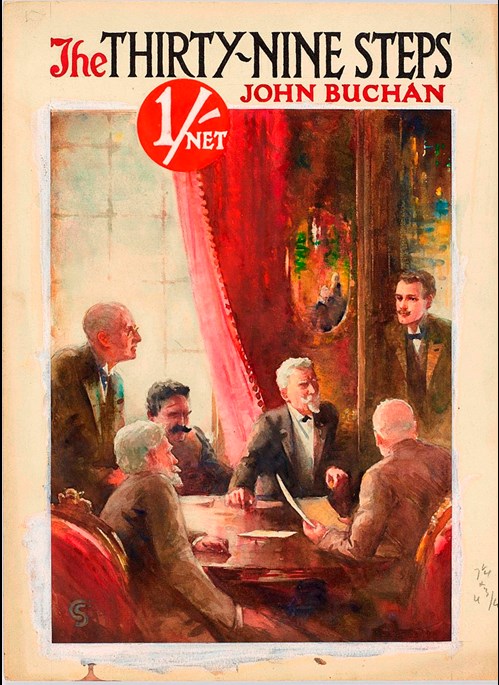

He studied law but turned to politics, no doubt influenced by his political friends, and served in South Africa as the private secretary of Lord Milner, the High Commissioner. Whilst in South Africa he began to write his first novel. His acclaimed espionage novel - The Thirty-Nine Steps - was in serialisation as the Great War threatened. It was published in book form in 1915 and Alfred Hitchcock later made it into a film definitive of the genre.

Above: The cover of the first edition of The Thirty Nine Steps

As a result of the wide readership of his espionage novel, and the knowledge he clearly demonstrated of the subject from his time in South Africa, he came to the notice of the Head of the British Government's top secret War Propaganda Bureau - Charles Masterman.

Above: Charles Masterman (circa 1906)

Buchan's first project was to write pro-British reports on the progress of the war. His grasp of the material impressed the Bureau and he was sent out to the Western Front as one of only five official War Correspondents. His work found the approval of the military hierarchy and he was posted the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF) HQ. There he produced official BEF communiqués. Throughout the War he continued to write books, mainly about the Great War, of which his 'Battle of the Somme, First Phase' (1916) and 'Battle of the Somme, Second Phase' (1917), were particularly well received.

In February 1917, Buchan returned to London to the appointment as Director of the new Department of Information. This department was primarily concerned with propaganda, but also had a role in civil and military intelligence.

After the war he continued his writing and at least 10 of his over 80 published books dealt with the role of the British forces in the Great War. Some sources maintain that post-war he still continued with his work in British Intelligence.

In 1935 he was appointed Governor General of Canada, a post he held until his death on the 11th February1940 aged 64-years.

John Buchan was a distinguished Scotsman who faithfully served his country in any capacity he was asked to undertake. Industrious, honest, discreet and intensely loyal, he and his kind left their mark on their country's history and, indeed, the whole world.

Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming

Born in 1859, to a middle-class family with the very common surname Smith, Mansfield, as he preferred to be known, had a conventional upbringing and won a place at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, England. In 1878 he graduated and was commissioned as a sub-Lieutenant. His first ship was HMS Belleraphon aboard which he spent seven years on duty in the Far East. Unfortunately, he continually suffered from seasickness. In 1885 he was classified as 'unfit for service' and put on the retired list.

For reasons that have not been fully explained, he was recalled to duty to serve with British Naval Intelligence, at that time a rather rudimentary organisation. However, in this capacity he made many journeys in the Germany and the Balkan States in the guise of a German businessman, which is surprising since it is said he did not speak German! Accordingly, he must have had enormous self-confidence to carry out the role of spy with the degree of competence he apparently exhibited.

Success in this role earned him promotion to the post of Director of the Foreign Section of the British Secret Service Bureau (SSB). During this period Mansfield Smith married and changed his name to Smith-Cumming by adding his wife's name.

In 1909, the British Government created the Secret Intelligence Bureau (SIB) to deal with public concern that there were active German spies in the country. In 1911 the whole security apparatus in the country was reorganised and Mansfield Smith-Cumming's SSB unit became the Foreign Section (MI6) of the new Secret (or Special Intelligence Service (SIS). It, as its name indicates, was given the responsibility for all secret work outside the UK.

Due to his habit of using the letter 'C' in green ink to initial the documents that passed across his desk, he became known throughout the service as 'C'. He also lost a leg in a car accident and thereafter sported a wooden leg.

Although Mansfield Smith-Cumming had a restricted budget before the outbreak of war, he managed to develop good basic surveillance system, particularly through his contacts in Russia.

Once the war started, more funds became available, and he greatly expanded the espionage network of his department. One of the most successful of his known operations was the collaboration of his Foreign Section with the Home Section (MI5) of SIS in the rounding up of 22 German spies in England, eleven of whom were hanged.

Other major espionage and intelligence successes were the reproduction of the German Order of Battle; the establishment of POW and agent escape routes; sabotage operations; the creation of a network of espionage agents in the occupied countries and a campaign of misinformation concerning British intentions.

Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming died in 1923 aged 64.

Mansfield Smith-Cumming became perhaps the best known of the British spymasters of the Great War. He was the classic British eccentric. At times he would startle his visitors by stabbing himself in his false (cork covered) leg with a knife, or scissors, and put at risk the life and limb of all at MI6 by careering through the corridors on a child's scooter. He also told very tall stories about his exploits, both real and imagined.

However, perhaps his greatest source of lasting fame is that the writer of the James Bond books, Ian Fleming, who was himself a member of Naval Intelligence in WW2, used him as the model for his 'M' - Sir Miles Messervy, Fleming's fictional Director of MI6. Apparently, over a billion people have seen 'C' portrayed as 'M' on the cinema screens across the world.

William Somerset Maugham

Indicative of the international life he would lead, Somerset Maugham, as he was always known in later life, was born in the British Embassy in Paris on the 25th January 1874. His father was a solicitor who worked for the British Embassy in France.

Both of his parents died before his teens and he went to live with his uncle, a parish priest, in Whitstable Kent.

Educated at King's School Canterbury, England and at Heidelburg University, Germany, where he studied literature and philosophy, he went on to study medicine at St. Thomas Hospital, London and qualified as doctor of medicine (surgeon) in 1897.

When he was 23 years old, his first book, 'Lisa of Lambeth', based on his medical experiences in the slums of London, was published to some success. His plays became popular on the London stage over the next ten years and he decided to give up medicine for the literary life.

At the outbreak of the Great War, the then 40-years-old Somerset Maugham volunteered for service with the Red Cross in France and worked with an ambulance unit whilst continuing his writing; perhaps his most famous book, Of Human Bondage, was published 1915.

In France, following the strange personal recruitment procedures of the time, Somerset Maugham was approached by the Head of British Military Intelligence in France, Sir John Wallinger, and asked to join the Service in the capacity of a contact between M16 in London and its espionage agents in Europe. No doubt Somerset Maugham's fluency in French was one of the prime reasons for his recruitment.

For a couple of years he successfully fulfilled this function in France and then Geneva in Switzerland. In 1917, he was sent to Russia (Petrograd) with the extraordinary mission of attempting to prevent the Russian Revolution by keeping the Menshevik Provisional Government in power and the Bolsheviks out. Self evidently, he was not successful in this endeavour.

Of the spies discussed here, Somerset Maugham's record is the most ephemeral. Certainly, he never dwelt on it, apart from his semi-autographical 1928 book, Ashendon: Or the British Agent. The interest of the general public was mainly concentrated on his literary success with his renowned short stories, books, plays, and later, his salacious public life. He married in 1917 and fathered a daughter, but since his Red Cross days in France he had had homosexual lovers and later, after his divorce, lived with them quite openly.

Accordingly, it is difficult to assess his success in espionage, but as for his own assessment of his literary career it was a self-deprecatory '?in the very first row of second-raters.' So, it is unlikely that he would have over-estimated his espionage work.

Further Reading

Carl Lody - the failed German spy - shot in the Tower of London