The Prince and the Pilot

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Prince and the Pilot

On a windswept hill overlooking the Yorkshire mill town of Halifax stands the area's most visible landmark: the Wainhouse tower. This is a Victorian-era construction and a 'folly'. It was, theoretically, built as a chimney for a local industrialist's factory, but it was never used as such.

Above: The Wainhouse Tower at dusk.

Adjacent to the Wainhouse tower is a former Methodist chapel. This Victorian building, like so many other chapels has seen better days, having closed as a place of worship in 2007 but at least it is still intact, and has been re-purposed for a local community support service organisation.

Above: The former Methodist Chapel at King Cross, Halifax, The Wainhouse Tower can be seen to the left.

Alongside the Wainhouse tower and the chapel is the Methodist graveyard, where are buried nineteen First World War servicemen. Among these is Lt JH Whitham of the Royal Air Force. There are no family details on his CWGC entry, but there is an intriguing reference on his headstone to a 'flying accident'.

Above: The Churchyard adjacent to the former Methodist Chapel at King Cross, Halifax

The family grave which includes Lt John Harold Whitham

What connects this family headstone in an unkempt churchyard on a bleak hillside in the West Riding of Yorkshire to the pomp and splendour of the Royal Chapel at Dreux, some 70kms west of Paris? This is the brief story of a connection which has been recently pieced together.

Bizarrely enough, the story starts in 1848 when the last Bourbon King of France, Louis Philippe, abdicated. He left France and spent the last two years of his life living in England. Although the title of 'King' passed down to his oldest son, the so called 'spare to the heir' was the King's second son (also called Louis) - the 'Duke of Nemours'. Moving a further generation down, we come to the Duke of Nemour's son - Gaston - who was titled Count of Eu. Gaston left France and married a Brazilian princess, Isabel in 1864. Between their marriage and 1889 when there was a coup in Brazil, two of their three sons were born. Following the coup the family were forced into exile and fled to France, where the two infant sons, Prince Pedro and Prince Luis, were followed by a third son who was named Prince Antônio.[1] They lived at the royal residence in the town of Eu.[2]

Above: The Chateau at Eu

With no country to rule, and no chance of reclaiming the French throne, the decision was made for the three sons to follow military careers. However, a law prevented members of the former French Royal family joining the military, so Pedro - followed later by Luis and Antônio enrolled in the Austro-Hungarian military school outside Vienna. From here they qualified but only Antônio seems to make a long-term career out of the army. He was still serving (aged 33) as a Hussar lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian army when war broke out. Clearly not prepared to wage war against the land of his birth and his ancestors, he looked to join the French Army, but the law preventing this course of action still applied.

* * *

Meanwhile, on 16th June 1915 John Harold Whitham had enlisted in the Canadian Field Artillery in Toronto, Ontario. On his Canadian enlistment papers, the 23 year old described himself as a bookkeeper and stenographer who had previously served in the 9th Lancers and Royal Engineers. He had bought himself out of the army by paying £18 in June 1913 and the following month left Liverpool on board the 'Victorian' landing in Canada on 24 July 1913. The manifest for the vessel lists him as a 'surveyor'.

On enlisting in June 1915 he stated his next of kin as being his father John Edwin Whitham of 6 Hanson Road, Halifax, in Yorkshire.

Less than two months after enlisting, John Whitham was sent overseas, as part 30th Battery (which was in the 8th Brigade CFA). Surprisingly, despite being physically fit and a pre-war regular, he was not destined for a combat role. This is almost certainly because during his pre-war service in the 9th Lancers (with whom he enlisted in 1910) and later the Royal Engineers he became a 'skilled clerk'.

In April 1916, just eight months after enlisting, he was promoted to acting Staff Sergeant. It seems he was transferred to the Canadian Army Service Corps in May 1916. His British service papers tell us he applied for a commission in the Artillery in July 1916, but this seems to have been turned down.[3] The papers again confirm his employment in civil life as 'surveyor' and also (like his father) an accountant. A further set of papers tell us that he served 2½ years at the Canadian Headquarters in London, in the directory of Supply and Transport.[4]

For some reason (perhaps he was bored) he applied for a commission again, this time in the Royal Flying Corps. By this time he seems to have been married, with his house being on Little Chester Street, Belgravia. It seems doubtful that a sergeant clerk would have been able to afford living in such an area on his pay, so it must be assumed this was a property that a number of clerks were billeted, so as to be close to their place of work.

The application was successful. He was discharged from the Canadian Army on 25 October 1917 in order to take up a commission in the RFC. On the western front, Prince Antônio was having a far more interesting war...

* * *

Somehow or other Prince Antônio had 'joined' the British Army in August 1914. How this came about is unknown and it may never have been formalised. From clues in the Prince's service records,[5] he seems to have served at the Headquarters of II Corps. In January 1916 Prince Antônio contacted Brigadier-General JEB Seely.[6] Seely allowed the prince to transfer to the Royal Canadian Dragoons with the rank of captain on 20 June 1916. He became the Canadian Cavalry Brigade's intelligence officer. [7] The appointment may have been easier due to the Prince being fluent in several languages.

Above: Prince Antônio photographed outside an unknown location. The author believes this location to be the Chateau d'Eu - look at the enlarged photograph from the front view of the chateau and the similarities to the background to the photo of Antônio. It is likely he was standing behind the bush in the photo taken during the war.

It seems the paperwork for this move only caught up on 2 December 1916 when Antônio signed his 'Officers' Declaration Paper'.[8] On this document his 'profession or occupation' was recorded as 'officer'. The fact that this had been an officer in the army of the enemy was not detailed, but perhaps it was a better option than stating he was waiting for a vacancy in the Royal houses of France or Brazil !

In mid-April 1917, supposedly as Seely’s principal brigade intelligence officer, Prince Antônio volunteered to crawl out at night into no man’s land and spent nearly 20 hours in daylight lying there unobserved: ‘watching, counting, drawing’. By 11 pm he had crawled back to the British line with ‘an exact account of the numbers of the enemy, the number of sentries, where they were placed, the exact position of the trench mortar and the machine guns, the number of dugouts with the number of men occupying each, the exact position of the wire … all portrayed on a beautifully drawn little map. When he took the place we found that this map and his description were accurate in every detail.’ [9]

It is in doubt that this incident took place on the date described, or if it did, Prince Antônio was not Brigade Intelligence Officer, because On 22 February 1917 Prince Antônio had been appointed Aide-de-camp to the GOC Canadian Cavalry Brigade, Brig General JEB Seely.

The citation of the MC, however, does back up the quotation above, it reads:

"For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. As intelligence officer he observed the enemy position at close range. Finally he got within 400 yards of the enemy in daylight, and though under heavy fire, continued his observation and obtained information which was of the utmost value."

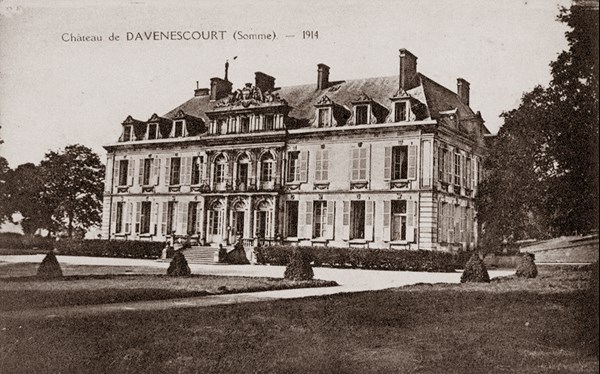

In March 1918 the Headquarters of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade was installed at the Château de Davenescourt, near Montdidier. The chateau was owned by a friend of the Prince Antônio – the Marquis de Bargemont. Attached to the brigade was war artist Sir Alfred Munnings,[10] and also at the chateau was William Orpen.[11]

Above: Château de Davenescourt

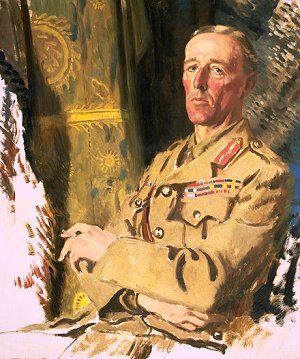

Orpen painted Brigadier-General Seely in ‘a large upstairs bedroom’ while Munnings painted Prince Antônio outside ‘on a black horse in the sunlight’.

Above: Brigadier-General The Rt Hon J E B Seely, CB, DSO, MP, 1918 by Sir William Orpen, IWM:ART 2982

Portrait of Captain Prince Antônio of Orleans and Braganza, 1918 by Sir Alfred Munnings, via 'Alfred Munnings Memory, The War Horse and the Canadians in 1918'

Munnings later recalled the situation was dreamlike as the brigade’s band played a selection of light classics in the château’s ‘outer hall’ while its officers dined luxuriously in the château’s main hall.

With the simultaneous and highly entertaining presence of Munnings and Orpen, both renowned raconteurs, Seely referred proudly to the château as his very own ‘École des Beaux Arts’.[12]

On 19 March 1918, the Marquis de Bargemont invited the brigade’s officers and Munnings to dinner at his château; Prince Antônio played the piano, Munnings sang one of his inimitable ballads and the officers of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade boisterously toasted the marquis. It was during this dinner that General Harman GOC of the Third Cavalry Division to which the Canadian Cavalry Brigade belonged, casually informed Seely, as the hors d’oeuvres were being removed, that deserters had recently revealed to him that the great German offensive would begin on 21 March.

During the famous Battle for Moreuil Wood on 30 March 1918, Seely realised he had to get a message to the British in Villers-Bretonneux to the left of the wood. He gave identical messages to Prince Antônio and Colonel Young of the Royal Canadian Dragoons. Young galloped off to the west of the village of Hangard while Prince Antônio was to try to reach Villers-Bretonneux direct. The prince had only gone 300 yards when his horse was killed beneath him. Seely’s orderly, Corporal King, promptly gave the prince a fresh, fast horse and he elegantly swung himself into the saddle and galloped away. Prince Antônio reached Villers-Bretonneux to deliver his message; Maréchal Foch later awarded the prince the Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur.[13]

Above: Prince Antônio d'Orleans et Braganza, MC by Sir William Orpen (signed: Orpen / France / March 1918)

On 21 May Antônio was detached for duty with the Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Munitions and on 18 July 1918 was seconded for duty with the War Office (in the Ministry of Munitions).

The above facts and timing of this is not surprising when it is realised that Seely had been relieved of command of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade on 20 May (having been gassed some months earlier). Brigadier General Seely (who was a serving Member of Parliament) was appointed the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Munitions on 10 July. The Minister of Munitions at the time being non-other than Winston Churchill. It is without doubt that the Prince Antônio would have come into contact with Churchill during his time at the ministry.

* * *

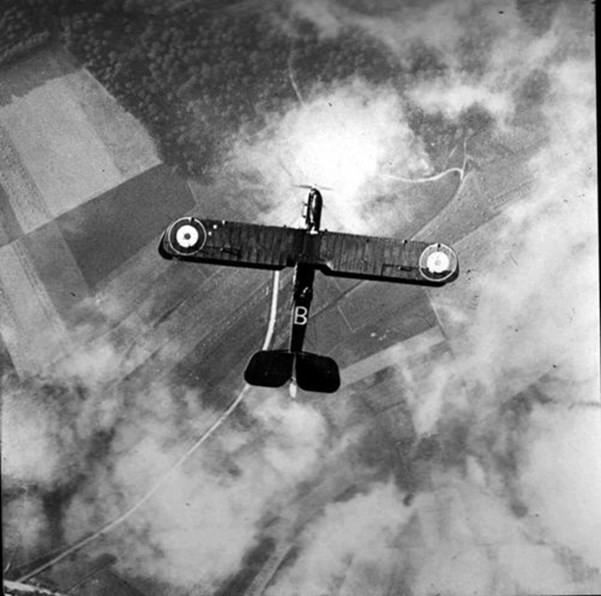

Meanwhile, John Whitham, having been discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force had gained both his commission and his pilot's wings. The indications are that he qualified in March 1918. It is not clear when he went overseas.[14] It seems that he served with 103 Squadron,[15] which flew DH9 bombers from its arrival in France in May 1918. They were based at Serny and Fourneuil, The Squadron moved to a new base at Floringhem on the 21st October 1918 and moved again to Ronchin on the 26th October 1918.

Above. A group of officers of 103 Squadron. Whitham would not have been part of this group, as it was probably taken at the beginning of 1919. It was certainly taken at the Hospital at Ronchin Lille where the Squadron was billeted. The building is still there and used as a specialist hospital and treatment centre for people with speech and hearing issues.

Above: An aerial view of the airfield at Ronchin

Above: A DH9 of 103 Squadron. The above photos are courtesy of the 103 Squadron website

In the last days of the war the Squadron was heavily engaged in attacking German airfields, railway stations, transport, and retreating troop columns with little or no opposition.[16]

A splendid photograph of a 103 Squadron DH9 in flight. Image courtesy of the 103 Squadron website.

After the end of the war, John was tasked with flying a DH4 from Marquise (No 1 Aircraft Supply Depot) back to the Central Despatch Pool at Southgate in UK.[17]

There is no record of how the paths of Prince Antônio and John Whitham crossed. It seems unlikely that they knew each other from the time they were working in Government offices as in October 1917 Whitham had been commissioned into the RFC and was certainly undergoing pilot training, and Prince Antônio only returned from France in May 1918.

The 'Canadian Expeditionary Force' connection is also likely to be a coincidence. Again, Whitham had relinquished this upon his being accepted for a commission, and it is unlikely Whitham - who would have had a Yorkshire accent would have 'connected' with the Prince who - although regimentally Canadian would have circulated routinely with RAF ferry pilots.

The most likely explanation is that Prince Antônio was visiting his family immediately after the war, and needed to return to his desk in London. The fact that he had visited the Chateau at Eu is mentioned above, so it is not impossible that this is where he was, immediately before he returned to London. The Chateau is located not far from the French coastal town of Le Treport. It is likely that the easiest way back to London was to hitch a lift in an RAF aeroplane. The Aircraft Supply Depot at Marquise is not far from the Chateau at Eu, and possibly Whitham was piloting the first available flight that was going back to the UK

Whatever the circumstances, the Prince seems to have hitched a lift on 26 November 1918, with what turned out to be fatal consequences.

Little is known of what happened on 26 November 1918. The facts are that a DH4 numbered F6078 was flying from No 1 Aircraft Supply Depot at Marquise in France back to the Central Despatch Pool at Southgate in UK, when they crashed in fog, with fatal results, at Old Soughgate, Middlesex. The pilot was Lt JH Whitham, and the passenger was Prince Antônio.[18]

John Whitham died on the same day, but Antônio - although badly injured - survived and was sent to the nearby Edmonton hospital. Unfortunately Prince Antônio died there two days later.

Above: Wounded soldiers outside the Hospital at Edmonton.

An enquiry was set up and it is recorded...

"The court hearing having duly considered the evidence are of the opinion that the accident occurred through the pilot being unable to see the ground owing to an extremely thick ground mist - apparently through no engine failure but in order to see the ground and find his bearings. The machine was completely wrecked and should be written off as a charge against the public."[19]

Under normal wartime conditions, there would not have been a repatriation of the Prince's body but the war was over the family obviously pulled strings and he his body was returned to France, where he was given the burial of a Royal Prince at Dreux

Above: The Royal Chapel at Dreux and the Mausoleum where Prince Antônio is now buried.

[1] Some sources refer to the third son as "Antione" but to be consistent, Antônio will be used in this article

[2] In 1964, the city of Eu acquired the château, in which, in 1973, it installed its City Hall and created the Musée Louis-Philippe

[3] The National Archives WO374/73949

[4] The National Archives AIR 76/545/4

[5] Library and Archives of Canada RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 1008 - 18

[6] The former Secretary of State for War who had resigned from Government following the Curragh incident in 1914

[7] At the time the brigade was part of the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division - it was to become the 5th Cavalry Division on 26 November.

[8] Library and Archives of Canada RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 1008 - 18

[9] 'Alfred Munnings Memory, The War Horse and the Canadians in 1918' edited by Brough Scott and Dr Jonathan Black (National Army Museum, London 2018) ISBN: 978-1-5272-2609-8 possibly quoting J.E.B. Seely, Adventure (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1930)

[10] Munnings's was employed as a war artist to the Canadian Cavalry Brigade, in the latter part of the war. During the war he painted many scenes, including in 1918 a portrait of General Jack Seely mounted on his horse Warrior

[11] Orpen was the most prolific of the official war artists he produced drawings and paintings of ordinary soldiers, and German prisoners of war, as well as portraits of generals and politicians.

[12] 'Alfred Munnings Memory, The War Horse and the Canadians in 1918'

[13] 'Alfred Munnings Memory, The War Horse and the Canadians in 1918'

[14] The fact there is no medal index card for Whitham initially led me to believe that he did not serve as an officer in an active theatre of war, however the fact that officers (and next of kin of officers) had to apply for British War and Victory medals suggests that these medals were not applied for, rather than him not serving in a war zone. My thanks to Tom Tulloch-Marshall for pointing this out to me

[15] The squadron was formed September 1917 as part of a large expansion of the RFC

[16] Losses for 103 Squadron for the period from May 1918 to the armistice amounted to

Killed – 23 - including 3 ground crew from unknown cause

Missing – 7 – Commemorated on Arras Flying Services Memorial

Died of injuries or possibly illness – 1 – Buried in UK.

POW/Died of wounds – 1 – Buried in Germany

POW - 7

POW/Wounded - 5

Wounded but safe – 6

[17] The 1 Aeroplane Supply Depot Marquise had some connection with a Pilots Pool. Whitham had probably left 103 Sqn and was held there prior to reposting. My thanks to David Fell (103 Squadron web site) for this suggestion.

[18] F6078 only arrived in France on 1 October 1918, and wasn't allocated to a squadron; it looks like it was used to ferry pilots and others between France and the UK. However, the aeroplane had been to France before, but as B2144, which arrived on 5 March 1918 and was allocated to No 27 Sqn on 22 April. It crashed just after take off for a bombing raid on 8 May (Lt Charles Henry Gannaway and Sgt W E A Brooks were not injured); the wreckage was rebuilt as F6078. Both crew members from B2144 were killed in action on 16 June 1918 when the aircraft they were flying that day (a DH4 numbered A7597) went down in flames after an encounter with enemy fighters during a bombing raid on Roye. My thanks to Gareth Morgan for this information.

[19] Source: http://www.rafmuseumstoryvault.org.uk/archive/whitham-j.h My thanks to 'Matlock' (Great War Forum) for this information.

David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Other media: A video of the Wainhouse tower:

Acknowledgements - my sincere thanks to the following individuals

Nigel Stevens

Tom Tulloch-Marshall

Gareth Morgan

'Matlock' (Pseudonym, GWF)

David Fell