The Unknowns Continue to Appear – the Work of the War Graves Adjudication Unit by Emma Worrall

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Unknowns Continue to Appear – the Work of the War Graves Adjudication Unit by Emma Worrall

[This article first appeared in the November 2020 Special Edition of Stand To! The Unknown Warrior: Fact, Fiction, Context and Legacy. Members received four copies of Stand To! and three copies of Bulletin every year along with any ‘Specials’ we produce. As a member you have access to the Stand To! Archive.]

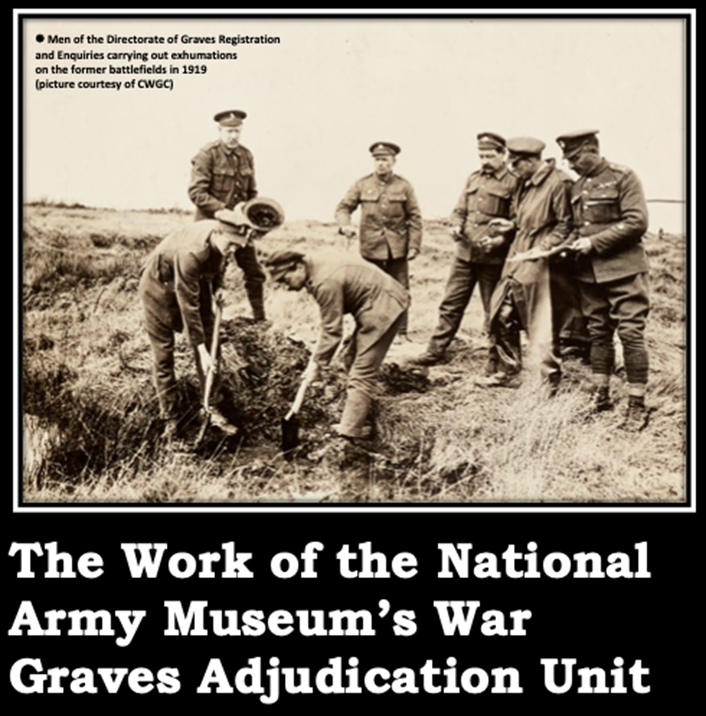

The War Graves Adjudication Unit (WGAU) was established at The National Army Museum in 2013 and works on behalf of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to fulfil its obligation to investigate the eligibility of Army personnel for commemoration by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The primary task of the Unit is to assess cases where it is believed, and evidence has been submitted, that an individual died as a result of service in the Army or in an auxiliary organisation during the First and Second World Wars.

The museum works on many different types of case, including those of individuals who are currently not commemorated, as well as the identification of service personnel buried in graves marked as 'unknown'.

In all categories, application has to be made to the CWGC in the first instance, which undertakes the initial verification of eligibility and assesses the evidence for the case. The National Army Museum only considers cases of service personnel from the British Army and Auxiliary Forces as the other service authorities (Royal Navy and Royal Air Force) have their own teams of assessors; other

Commonwealth countries enjoy their own equivalents

When a case for commemoration of an individual of the British Army is submitted to the CWGC Commemorations Team it is eventually passed by them to the WGAU as the Service Authority. All cases are first submitted to the CWGC before they move on to the next stage of the process.

Eligibility

There are a number of stages each case has to go through in order to be successful. The first is to meet the basic eligibility criteria, the first of which include two distinct time periods for commemoration for those who died as a result of service in the First and Second World Wars. They are: 4 August 1914-31 August 1921 and 3 September 1939-31 December 1947. Once these criteria have been met there are further considerations for eligibility for those who died in service or after discharge.

In reality, most of those who died on active service overseas are already commemorated either in an

individual grave or on a Memorial to the Missing. Although cases do arise where individuals who have died overseas in action or at home whilst still serving are not on the CWGC’s Debt of Honour Register, the vast majority fall into the category of those who have been discharged from service and have died before the end of the relevant commemoration period. Most cases relate to individuals who died during the First World War or in the years after the Armistice. This is no doubt partly due to the availability of records, whereas those relating to the Second World War and its immediate aftermath are less numerous, with many still being held by the MoD.

An individual can be identified as having been ‘in service’ when they died regardless of whether they were on active operations, home service, leave or furlough. The key consideration is whether or not they were subject to military discipline at the time.

To demonstrate the process and eligibility criteria relating to non- commemoration cases, those cases which relate to death in service will be considered first. For an individual to be identified as having been ‘in service’ when they died, this includes soldiers who were on active operations or on home service, as well as those who were on leave or on furlough. The key consideration for such a case is whether the individual would be subject to military discipline or not. Obviously, anyone on active or home service would be, and this would extend to those on leave or furlough. However, it would not include those discharged to certain sections of the Army Reserve, especially those demobilised to Class Z after the Armistice.

If the serviceperson under investigation is identified as being in service at the time of their death, the specific cause of their death is irrelevant, and they qualify for commemoration by the CWGC. Yet for a case where the individual has been discharged from service a much more detailed examination is required, specifically relating to their cause of death and their military service, as it is necessary to show a connection between the two in order for them to be commemorated by the CWGC.

Cases Submitted

Cases are invariably submitted by members of the public, but the reasoning behind the submission and how they became aware of the individual can be quite varied. Sometimes the enquirer has a tangible relationship to the individual whose case they submit, such as a familial link. Or they might have become aware of the casualty from research into the local area – perhaps whilst investigating a war memorial or cemetery, or whilst using a specific source such as a Roll of Honour or newly released series of records (the WFA Pension Ledgers and Cards, for example). Alternatively, a potential candidate for commemoration might be derived from a more obvious source such as the Silver War Badge Roll or a Service/Pension Record where the soldier has been discharged under a medically unfit category (such as paragraph 392 xvi of King’s Regulations for First World War cases). On occasion these records can provide the basis for a case, but further evidence is often required and, even if an individual is recorded as having been discharged for a medical reason (whether sickness or injury), it does not always result in a positive adjudication. As already stated, as full an assessment as possible is necessary to ascertain the circumstances of the discharge of the individual in relation to their service and their subsequent death.

Types of Records

Whether the case is one of in-service or post-discharge death, a significant number of the records used to provide evidence in a case are the same: Soldiers’ Effects Registers (the originals are held by the National Army Museum), Service and Pension Records, Medal Index Cards, Medal Rolls, Silver War Badge Rolls as well as civil records such as Census, Probate and parish records. During some investigations, due to the specific nature of the case, other records become important, such as war diaries for overseas in-service deaths, Hospital Records (MH106 series), Widows’ Pensions (PIN82) and the surviving selected First World War Pensions Award files (PIN26). The WGAU always uses all the available sources to provide a full assessment of a case, as well as to be able to confirm other facts such as age at death, regimental particulars and, if it’s not already known, place of burial.

Assessment

When the WGAU begins working on a non-commemoration case, there are a number of processes that are carried out and, even though some cases can look similar because of the stylised wording used in official documentation, or the survival (or not) of specific types of printed forms common to all service and pension records, in reality no case is the same and each has to be taken on its own merits to ensure that a conclusion reached is based solely on the evidence relating to that individual.

‘Are we dealing with the same person?’

The first step when considering a new case is to assess the evidence submitted, including looking at what type of records have been used - whether civil or military - and what information they convey about an individual, particularly any details about their cause of death or occupation which might be necessary in order to make a link between military service and death.

It may not be an obvious part of the process but, in every case, it is of paramount importance to first make sure that the individual who is recorded on the death certificate, and whom the case is about, is the same individual who appears in any submitted military documents. Establishing whether this is in fact the case is made by finding a number of points of corroboration between the death certificate (which as a civil document does not always record a regimental number) and the military records (especially in a post-discharge case). In doing so, it is always necessary to keep in mind when carrying out any type of historical research the reason why certain types of records were created, as this helps to identify how useful they might be or if they will provide the evidence for which you are searching. More often than not, multiple records are used to make the necessary links between a civil death certificate and the individual recorded in military records.

It is not always difficult to find these links. For example, the same name and date of death given on the death certificate might appear in the Soldiers’ Effects Register or a Pension Ledger/Card. Alternatively, the fact that the name of the informant of the death matches the beneficiary of a soldiers’ effects account can provide a clear indication that the records all relate to the same individual. The same informant might also be the next of kin from the Service/Pension record, or the place of death or home address of the deceased matches that given in a military record. Moreover, the death certificate, although primarily a civil record, can sometimes record military particulars under the occupation/profession heading - including service number, battalion and regiment - which are helpful in linking the two types of documents to the same person.

Having seen a large number of death certificates, I can attest that some of the most helpful are those from Scotland. Scottish Death Certificates potentially provide numerous points of corroboration as they not only record whether the deceased individual was married - this is recorded under their name, along with their occupation - but also give their parents’ names, including the maiden name of the mother, as well as recording the informant of the death.

In some circumstances an individual might not die at their home address - they may be in a local hospital or perhaps much further away from home receiving treatment - and, in such instances, although the informant is still sometimes a member of the family, more often than not the informant is a member of the institution’s staff. This can mean that the usual ways used to link the civil and military documents (matching the place of death to an address in a service record, or the name of the informant of death matching the beneficiary of the Soldiers’ Effects register) are absent and other records have to be used, entailing a more drawn out investigative process. In a recent case in which the informant of death was the brother-in-law and only minimal links could be made between the civil and military documents. Otherwise, it came down to discovering a link through this brother-in-law.

First, it was necessary to identify that the deceased only had two sisters, one of whom it transpired would have been too young to have married by the time her brother had died, and then finding the corresponding marriage to match the names. Unfortunately, in this example, the name of the remaining sister – ascertainable from census records – didn’t correspond with the name of the woman who married the brother-in-law (the reason being that, in the marriage index, the first and middle names were the opposite way around to how they were written in the census records).

In order to try and establish a connection, the service record of the brother-in-law was found and confirmed his marriage (as he had been in service at the time it took place) together with the wife’s home address, an address which matched the deceased’s (her brother’s) from the death certificate. Although the case’s resolution was a little more drawn out than other cases can be, the necessity to show that the records relate to the same individual is a prerequisite stage the WGAU goes through before eligibility is considered.

Do the military records substantiate a case?

Once the link between the civil and military records has been made, consideration is given to the military service of the individual, including all aspects which would be relevant for commemoration, including rank, unit (regiment and battalion), dates of service, age on attestation and discharge, and any eligibility for campaign medals.

Information regarding an individual’s discharge, and the cause of it, can vary from a full and detailed set of medical inspection reports and pension award forms to a single entry on a pension card or silver war badge roll. The WGAU assembles all the information, both that submitted and that which it can identify from its own efforts, in order to create the biggest picture possible and to make an informed assessment of the evidence. Sometimes the links between service and death are very clear, either because the recorded cause of discharge of an individual is the same as recorded on a later death certificate, or because the cause of death derives from an injury which is undoubtedly the result of war service. In other cases, the certifying doctor has sometimes commented on the relationship of the cause of death to war service.

Sometimes the case requires a more detailed review, entailing research in the collections of other organisations to try and find the evidence necessary.

The sources the WGAU will consider range far wider than just military ones and include electoral registers, asylum records, hospital records, workhouse and parish records, and school registers.

Although many of the cases appear very similar, they all provide a unique challenge, not only in trying to trace the military service of an individual, with all the problems inherent when dealing with incomplete, sample and partially destroyed records, but also when adjudicating post-discharge cases. These often only commence following a soldier’s leaving the army, it is necessary to follow the individual into civilian life.

As with many types of research, one thing leads to another, and there have been some interesting opportunities to gain further knowledge about, and a greater understanding of, some of the drivers of Contemporary decision-making, such as the Royal Warrant on Pensions, an essential aid in translating the meaning behind the various articles recorded on pension records. Certain names also recur in the pension records, and the signature of William Sanger, the Controller at the Soldiers’ Awards Branch – which was situated at Burton Court, just on the opposite side of the road from the Museum today – is an especially familiar sight.

Corporal Brown and Lance Corporal Kellow

After discussing some of the procedures that the WGAU has in regard to non- commemoration cases, it is pertinent to provide a few examples of their implementation. Two very poignant cases put forward for death in service commemoration were those of Corporal Harry Brown and Lance Corporal William Henry Kellow, both of the 1st Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers, and both of whom died on 22 December 1920 at Crownhill Barracks in Devon.

The National Army Museum has the enlistment books for the Royal Munster Fusiliers, as well as those of the other Irish Regiments that were disbanded in 1922, the Connaught Rangers, Leinster Regiment, Royal Dublin Fusiliers and Royal Irish Regiment. These very informative registers, which are digitised and available on the Museum’s website at https://www.nam.ac.uk/soldiers- records/persons contain details of those soldiers who enlisted during the period 1920-22, including those still serving who had fought in the First World War but were notionally deemed to have re- enlisted after receiving their new army service numbers. The enlistment books summarise, where applicable, previous service, including any First World War service and medal entitlement, as well as original enlistment dates, age, next of kin and home address.

Fortunately, Corporal Brown and Lance Corporal Kellow are both recorded in the Royal Munster Fusiliers’ enlistment book. Harry Brown’s entry records that he attested on 4 February 1914 when he was 18 years and four days old. His trade on enlistment was ‘beer bottler’ and he was born in St James, Grimsby, Lincolnshire. It also states that he had served with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1915 and 1918 and the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MF) 1915-1918, and that he was eligible for the 1914-15 Star and the British War and Victory Medals. The record also gives his place of death as Crownhill Barracks, which matches the place of death recorded on his death certificate. The Soldiers’ Effects Register also records the same place and date of death as noted in the enlistment book.

The enlistment book entry for William Henry Kellow, meanwhile, records that he had originally attested on 11 December 1908 at when he was 15 year and 283 days old.

His trade on enlistment was ‘shop boy’ and, like Corporal Brown, he had served in the First World War, albeit that he was a Prisoner of War from 1914 until 1918. It was therefore possible to follow this new information through and discover further details of William Kellow’s time as a prisoner. This took a while because his name was recorded on his International Committee of the Red Cross Index Card under the misspelt name ‘Callow’. However, the other regimental particulars matched, so it became clear that it was the same individual, and it eventually transpired that although the name on the card was misspelt, the name on the actual German register entry was spelt correctly. What we were dealing with was a mis-transcription of the original, something which can often cause researchers a number of problems!

An inquest was held on 23 December 1920 into the deaths of Harry and William and, the following day, a newspaper reported that the gas had been found fully on in the room where the two men had had their bunks; a verdict of accidental suffocation by an escape of gas was returned. Thanks to the submission of their cases by a member of the public, these two men are now commemorated by the CWGC.

Identification Cases

The WGAU also provides historical investigation into cases of burials where the casualty is currently remembered only as an ‘unknown soldier’ or is

somehow only partially identified. These cases can be presented in a variety of forms and be based on a similar variety of evidence as one finds with non- commemoration cases. However, in one respect they are completely different. The main focus of investigation is on the precise location of those specific unit(s) which traversed the ground from which the unidentified burial had originally been recovered. Otherwise, the specifics of each case vary in terms of information about both the grave itself as well as the number of candidates, type of unit, etc.

Some graves, despite having no identification, often have some fairly specific attributions which allow cases to be made as to whom the grave may belong, for example, date of death, rank, regiment, and battalion; sometimes all of the above are present or a mixture. Once again these cases are submitted by a wide range of people, from family members to research groups and unrelated individuals. Depending on the specific circumstances of the grave under consideration, the number of potential candidates can be from one to many dozens.

Obviously, the more candidates, the longer it takes a case to be fully researched. Each candidate must be sufficiently discounted - an undertaking which includes a lot of biographical research drawing upon sources such as medal records, Soldiers’ Effects, rolls of honour, service records and casualty lists. The circumstances of a candidate’s death are also required, which entails the investigation of a number of different sources spanning regimental histories, personal accounts, battalion, brigade, and division war diaries, Adjutant and Quartermaster diaries, Assistant Director of Medical Services and Field Ambulance diaries, as well as prisoner of war records, missing personnel files and many more. The WGAU is often in contact with the relevant regimental archive/museum in order to make sure every base has been covered. The collections held by the National Army Museum are also important, encompassing not just the books, journals and archive collection but the uniform collection and the specialist knowledge of colleagues across departments within the Museum, all of which adds to the great wealth of guidance and expertise which the WGAU is able to utilise.

These types of cases provide a different challenge compared to the non- commemoration cases as the context of the location of the burial, and the events which took place in the lead up to the internment - and also often a long time afterwards (especially when a regiment may have fought over the same area more than once) - are key in order to establish a link between the burial and the candidate. Once again, each case is different and may require a different approach or a different reliance on certain sources, but clear and convincing evidence must be found in order to prove the identification of the grave. The adjudication of the WGAU is then returned to the CWGC and Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC) as, in this instance, the MoD makes the final decision.

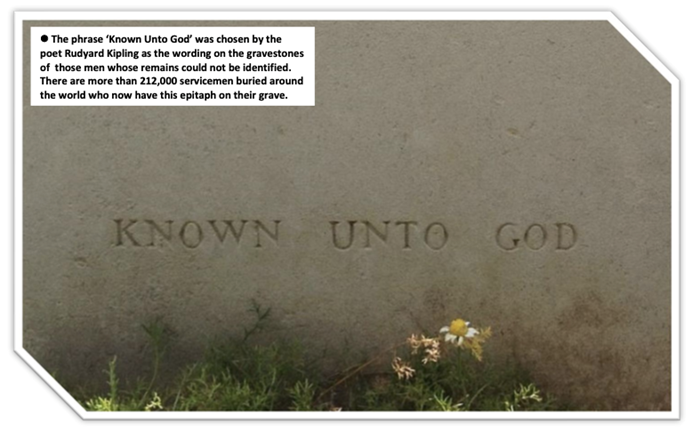

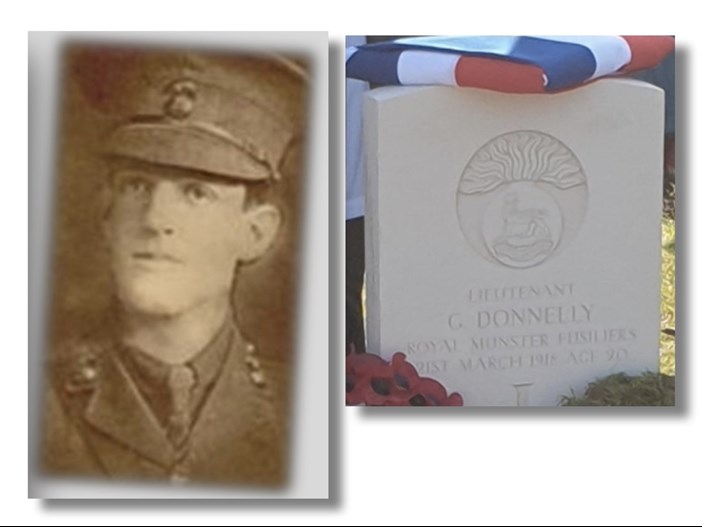

The Grave Rededication of Lieutenant Donnelly

When an identification is confirmed by the MoD it is possible for the CWGC to replace the headstone with one identifying the individual buried there, often with an epitaph chosen by the family. The JCCC organises a service of remembrance which brings together those involved with the case, family and military representatives. These services are arranged with great attention to detail and, judging from the few at which the WGAU has been present, they provide an opportunity for personal and group reflection on the individual whose identity has been reclaimed and his sacrifice. They also reflect the continuity between the work started more than a century ago beginning with the early battlefield cemeteries, the wholescale clearance of the battlefield after the First World War, and the reorganisation and order bestowed by the IWGC, to the work that goes on to this day in identifying those who lost their lives in both World Wars.

One of the services the WGAU was present at took place on 21 March 2019, when the grave of an officer who died during the First World War was rededicated on the 101st anniversary of his death. Lieutenant Gilbert Donnelly was killed on 21 March 1918. The morning of his grave rededication service was foggy, just like the morning of 21 March 1918 had been, which made the day all the more fitting. There was a large gathering at St Emilie Valley Cemetery for a service which was conducted by the chaplain of the 1st Battalion, The Royal Irish Regiment. The family of Lieutenant Donnelly were heavily involved in the service, adding music and readings alongside the always moving recitation of the Kohima Epitaph, the sounding of the Last Post and of Reveille, and a minute’s silence.

For me, standing to the side of the grave of Lieutenant Donnelly, as a wreath bearer, meant that I was opposite the majority of the Donnelly family. It would have been impossible to miss how poignant not only identifying the final resting place of their relation was but the importance to them of the opportunity to be able to participate in a service of remembrance. The inscription of Lieutenant Donnelly’s headstone reads ‘Son of John and Jemima, Glastonbury Ave, Belfast. He was lost and is found’.

Mapping the ground in Delville Wood

Another more recent case related to the original communal grave of four men who were found in Delville Wood on the Somme after the war and were reburied at London Cemetery Extension, High Wood. Two were identified at the time and the other two, apart from their regiment and in one case, their rank, were unknown. One of these was a Corporal of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Because he was found with two identified members of the 10th Royal Welsh Fusiliers it was suggested that he was likely to have been from the same battalion and to have died on the same day. This is a good place from which to start and, in light of what is known of the whereabouts of the 10th Battalion towards the end of July 1916, there was context to the claim.

It was then the WGAU’s role to carry out additional research, which included discounting all other potential candidates from other battalions and other periods of the war. Eventually all of the necessary steps described above had been taken and it was possible to pronounce that the grave belonged to Corporal Robert Owen Davies of the 10th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

Reflections

Throughout the WGAU’s work it is always important to be able to verify any claim put forward in a case and, where possible, to add additional weight to the hypothesis advanced. This allows us to demonstrate that we have contributed to the historical knowledge surrounding the case but also that we have tested the durability of the theory, acting in effect as devil’s advocate in order to provide a full assessment. While it is true that not all cases pass, because sometimes the evidence uncovered introduces too much doubt to allow such an outcome, the overriding determination of the WGAU remains to arrive at a decision, whether positive or negative, consistent with the available facts.

In conclusion, the work done by the National Army Museum’s War Graves Adjudication Unit forms a part of a much larger process which is contributed to by many organisations, the JCCC, CWGC, other service authorities as well as by members of the public, all of whom have the same aim - to commemorate those of the First and Second World Wars whose death resulted from their service. For the museum’s part, it is a role which requires a lot of mosaic-like research in order to piece everything together, with sometimes the tiniest tessera of information helping contribute to a greater understanding of an individual, their life and their death. I have always felt that research never really comes to an end, that there is always another angle or another repository to try. While this might seem exhausting work it is the embarking on this type of endeavour, groping for the possibility that there could be something in the next archive which will make (or break) a case, that supplies all the motivation one needs.

None of this work would be possible without the public- spirited individuals who seek out these potentially identifiable graves or those soldiers who died and are currently uncommemorated, putting so much hard work and effort into building cases and submitting them to the CWGC. Not all the cases pass - they never could when one considers the reality and limitations of the sources available with their inherent problems, exclusions, mistakes, different viewpoints and, crucially, the fact that the records were not created for the reasons for which we are now trying to use them. But this has never discouraged those who submit cases, which is admirable.

On a more personal note, I’ve spent many years going to the battlefields and visiting those cemeteries which are the final resting places of my own relatives. I have always treated the cemeteries with respect and reverence, but it is fair to say that since starting my present job three years ago they have now taken on a completely different personal meaning for me. In my mind they had appeared to be stationary, fixed somewhere in the past but now I know that’s not the case. They are in flux, with amendments to them being made all the time; they are living, not static, and I find it very humbling to have the opportunity to be a small cog in the large machine which keeps this cycle moving.

There is an importance today, just as there always has been, to the task of being able to identify and locate as many of the fallen as possible, and that feeling still abounds within those carrying on this work. No matter what part of the process one fulfils, big or small, there is a feeling of carrying on the work that began more than 100 years ago and of continuing to do the very best for those

of our army who died. One of the prevailing thoughts I have is of the individuals, whose names are brought forward as possible candidates for a grave identification. If the case passes, that is a fantastic outcome for everyone involved, most especially the soldier in question and also their descendants, but I often find myself thinking of all those individuals who were investigated and who were discounted. In one sense I feel sadness at not being able to identify their grave but in another way I feel glad that they have been considered, whether through digitally available sources, by seeing their original service record at The National Archives, reading about their last actions in the regimental history, reading an obituary or finding their name on a war memorial, because it is still a form of remembrance, simply by the act of thinking about and researching that individual, which shows that they have not been forgotten.

Article by Emma Worrall

Emma Worrall has worked at the National Army Museum since 2017. Her specialisms are across the history of the First World War, the commemoration of the First and Second World Wars, and in the role of animals during the First World War. She holds an MA in British First World War Studies from the University of Birmingham and is currently studying for her PhD in the military employment of dogs in the First World War, at the University of Chichester.