The US 2nd Division at Blanc Mont Ridge by Major General by David T Zabecki

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The US 2nd Division at Blanc Mont Ridge by Major General by David T Zabecki

[This article first appeared in the October 1918 edition of Stand To! No. 113]

The US 2nd Division’s capture of the heavily– defended German positions on Blanc Mont Ridge on 3 October 1918 was arguably the most ingenious and skilfully conducted American divisional attack of the Great War. Ironically, however, Blanc Mont today is one of the least remembered of the American Great War battles for two primary reasons. First, the veteran 2nd (‘Indianhead’) Division – along with the green 36th Division – was fighting in the sector of the French Fourth Army, some 20 miles to the west of the main sector of the US First Army. The American main force was at the time heavily engaged in the Meuse–Argonne sector in what was then, and still remains, the single largest battle in American history. And second the tactics and scheme of manoeuvre devised by the 2nd Division’s innovative commander, Marine Major General John A Lejeune, departed significantly from the rigid and dogmatic tactical doctrine of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under General John J Pershing. During the course of the war, in fact, the 2nd Division was the subject of official criticism by the AEF’s Inspector General, Major General Andre W Brewster, for failure to follow approved American tactical doctrine—regardless of any actual battlefield success. David T Zabecki here argues that the battle for Blanc Mont Ridge, fought by the ‘Leathernecks’ of the 4th Marine Brigade and the Army ‘doughboys’ of the US 3rd Infantry Brigade, had a greater strategic influence on the outcome of the war than the far more famous battle in which they had been engaged at Belleau Wood the previous June.

Strategic Objectives

In the autumn of 1918 the Germans were losing the war on the battlefield. After the five massive but strategically bankrupt Ludendorff offensives from 21 March to 15 July 1918, the Allies went on the offensive on 18 July, and never again yielded the initiative.

By the third week of September they had erased all of Germany’s 1918 gains and had pushed the Kaiser’s army back to the Siegfried Line – what the Allies called the Hindenburg Line. Then on 26, 27, 28, and 29 September, the Allies launched a sequential series of four large, converging attacks from Flanders to the Meuse River which were designed to crush the Germans once and for all. Under the leadership of Allied Supreme Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch, all four prongs of the Allied General Offensive were focused on cutting Germany’s key strategic rail lines and capturing all their vital rail centres west of the line running from the River Meuse to Antwerp. The Franco–American attack, which opened the General Offensive on 26 September, had the objective of overrunning the rail center at Mézières, and in the process pushing the Germans out of the Champagne region on the left, and the Meuse–Argonne sector on the right. Attacking generally south to north, the US First Army had the difficult and compartmentalised area from the eastern edge of the Argonne Forest to the Meuse; the French Fourth Army under General Henri Gouraud had the more open sector from the city of Reims to the western edge of the Argonne.

Anchor Position

The German Army may have lost the battlefield initiative, but it was still capable of putting up a stiff fight. They were especially well dug into their positions in the Champagne, having occupied that sector in 1915 and successfully defended it ever since. The main defences of the Siegfried Line in Champagne ran about 5 miles behind the most forward German positions on 26 September. The emplacements on Blanc Mont Ridge, between Sommepy and St Etienne, were the anchor of the line. Under the overall command of the German Third Army, the position was held by the 200th and 213th divisions, supported by elements of the 17th, 195th and 203rd divisions. Both the 200th and 195th were composed of three regiments each of elite Jägers, widely regarded as some of the German Army’s toughest and most skilful fighters. From the high ground running from Blanc Mont in the west, to Schlesier Hill (Hill 210) in the centre and Médéah Hill in the east, the Germans had observation across the entire sector. Roughly 20 miles behind the Siegfried Line, the somewhat less formidable Brünhilde Line ran along the northern banks of the River Aisne. If the Germans could delay the French Fourth Army along the Siegfried Line long enough, a gap would open between the French and Americans, exposing the US First Army’s left flank. That is exactly what happened by 30 September.

After more than four years of war the French Army was in a state of near exhaustion. The horrendous blood lettings of the failed French Champagne Offensive of 1915, the meat– grinder defence against the German attack at Verdun in 1916 and the disastrous Nivelle Offensive against the Chemin des Dames in 1917 had bled the French Army white. Then the 1917 mutinies sapped whatever was left of French morale. When General Philippe Pétain was brought in as commander of the French Army after the mutinies, he spent more than a year patiently and methodically rebuilding and restoring his force. What Pétain had accomplished was next to miraculous, but even by the autumn of 1918 the French Army was still the Allies’ weakest reed. Gouraud’s Fourth Army tried repeatedly, but after four days of fierce fighting his troops were stalled a little more than 2 miles south of the Blanc Mont Ridge.

Gouraud was forced to ask Pershing for the temporary loan of some fresh American forces to help take the ridge. Once Blanc Mont fell, ran the thinking, then the rest of the Siegfried Line in Champagne would go with it and the Germans would have little alternative but to withdraw north to the Aisne. Understanding the importance of keeping the French closed up on his own left flank, Pershing reluctantly agreed to detail two American divisions to Gouraud. On 1 October AEF Headquarters issued the orders attaching the US 2nd and 36th divisions to the French Fourth Army’s XXI Corps. On paper it was a significant force of almost 54,000 troops, because an American division of 1918 was roughly twice the size of either a French or German division of the time. The veteran 2nd Division was one of the best and most battle– hardened outfits in the AEF. The totally green 36th Division was an entirely different matter. The troops from Texas and Oklahoma had been in France for only two months. They had not yet been under fire, and the division had not even completed its initial cycle of training.

Doctrine and Disdain

America entered the Great War after the other belligerents had been at it for almost three years. AEF commander Pershing arrived in France in May 1917 with a complete disdain for the trench warfare that had characterised the fighting so far. He was convinced that neither the German generals nor his Allied counterparts understood how to fight a battle of ‘open warfare’, what we today would call manoeuvre warfare. Pershing had an unstinting faith in America’s national exceptionalism and a near religious belief in the superiority of American rifle marksmanship and the traditional psychological power of the bayonet. He fervently believed that the tired and dispirited Europeans, hunkering down in their trenches, could never stand up against his strapping and vigorous American doughboys. Pershing especially blamed an over–reliance on artillery support for the stagnation of trench warfare, and he discounted the concepts of combined–arms warfare that integrated the effects of new weapons like machine guns, trench mortars, rapid–firing artillery, and aircraft. Ignoring all the lessons of the past three years, Pershing right to the end of the war advocated ‘self–reliant infantry’. As a result, the AEF’s doctrine pushed American troops forward in relentless frontal attacks, ever trying to achieve that magical break–through that would lead to ‘open warfare’. But after three years of trying the same thing and failing miserably, the other Allied generals had finally come to accept that the still primitive battlefield mobility technology of the Great War period made such tactics impossible in the face of massive modern firepower.

Unity

Major General John Lejeune assumed command of the US 4 Marine Brigade on 24 July 1918, and four days later he was assigned command of the 2nd Division. He was the first Marine to command an American division in combat, although not to command a division – that honour belonged to Brigadier General Charles A Doyen, who had commanded the 2nd Division for two weeks in 1917. Considered the father of the modern Marine Corps, Lejeune later served as its 13th Commandant from 1920 to 1929. Although he had not been part of the 2nd Division during the Battle of Belleau Wood from 6–26 June 1918 or the Battle of Soissons from 18–22 July, he had studied those actions closely and had drawn lessons that were very different from the AEF’s official doctrine. As he later wrote:

‘The key to combat effectiveness is unity – an esprit that characterises itself in complete, irrevocable, mutual trust. Now my infantry trusts my artillery and engineers, and my artillery and engineers know this so they will go through hell itself before they let down the infantry. My infantry believes that with such support they are invincible – and they are.’

He first tested and refined his tactical theories on a large scale during the Battle of Saint– Mihiel (12–15 September 1918).

Lejeune also had the benefit of a solid senior command team, who agreed with his tactical thinking. Actually, all three of his brigadier generals had more direct combat experience than he had acquired by that time. The commander of 3rd Infantry Brigade was Brigadier General Hanson E Ely, who as the commander of the 28th Infantry Regiment had led America’s first offensive battle of the war to capture Cantigny on 28 May 1918. By the time of the Blanc Mont battle Ely had already earned the Distinguished Service Cross and three Silver Stars. A week after Blanc Mont he assumed command of the 5th Division. He retired from the army in 1931 as a major general in command of II Corps.

The commander of 4 Marine Brigade was Brigadier General Wendell Neville, who had earned the Marine Corps Brevet Medal during the Spanish American War, and the Medal of Honor at Vera Cruz in 1914. He was one of only three Marine officers (along with Smedley D Butler and David D Porter) to hold both the Medal of Honor and the Brevet Medal. Neville commanded the 5th Marines at Belleau Wood, and he knew first–hand the brutal lethality of modern firepower. In 1929 Neville succeeded Lejeune as Commandant of the Marine Corps. The commander of the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade (2nd F A Brigade) was Brigadier General Albert J Bowley, who had commanded the brigade’s 17th Field Artillery during the Belleau Wood fight. Bowley ended the war as commander of US VI Corps Artillery and he retired from the Army in 1938 as a lieutenant general and the commander of Fourth Army.

A Promise

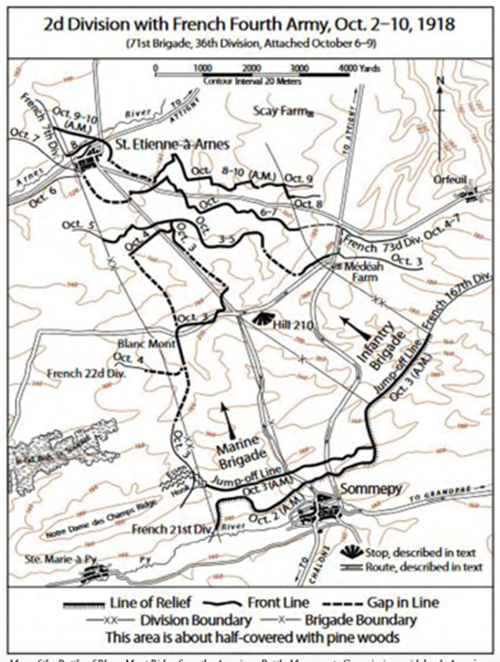

As his troops were moving up, Lejeune learned that the French intended to split his division up and use his units piecemeal to reinforce the French divisions that were already in the line. In order to head that off, Lejeune promised Gouraud that if he put the 2nd Division into the line on a narrow front and gave him adequate support on the flanks, then the Americans would take the ridge and hold it. Gouraud agreed. On the night of 1–2 October, Neville’s Marine Brigade relieved in place the French 21st Division on the left, and occupied a line roughly a mile long running from the Sommepy–St Etienne Road on the right to the German–held Essen Hook trench system on the left. The following day Ely’s infantry brigade relieved the French 167th Division on the right, and assumed a line a little more than one mile in length to the northeast of Sommepy. The two American brigades, however, were not directly adjacent to each other. There was a gap of a good mile–and–a–quarter between them. The Marine brigade faced north by northwest; while the infantry brigade faced northwest. The 2nd F A Brigade, meanwhile, put its guns into positions to cover both brigade sectors. Reinforced with French heavy guns, 2nd F A Brigade had control of 120 light and 72 heavy guns. Each manoeuvre brigade was also reinforced with a battalion of French light tanks; a total of 48 machines.

Dispensing with Doctrine

The attack was originally scheduled for 2 October, but the day before Lejeune requested a 24–hour postponement, which the French command granted with great reluctance. Lejeune had good reasons for wanting the delay. For one, Neville used 2 October to clear many of the Germans out of the Essen Hook trenches on his left, which would have threatened his flank once the assault started. Lejeune also wanted more time for his guns to get into position; but more importantly, the extra 24 hours would give his gunners the opportunity to coordinate their fire planning with the infantry commanders, and also allow reconnaissance of the ground and target areas in daylight. Lejeune was clearly planning a methodical, limited objective, set–piece attack in contravention of the AEF’s ‘open warfare’ doctrine.

The scheme called for the two brigades to make converging attacks toward the top of the ridge that would pinch out the triangle of open space between their inner flanks. It was a bold but risky manoeuvre by Great War standards. The point of convergence was roughly about Hill 210. Once the primary objective was secure, follow–up reserves would mop up any German positions that had been cut–off in the triangle. Advancing in column of regiments, the 6th Marines were to lead the attack on the left, with the 5th Marines following in support. On the right, the 9th Infantry would lead, followed by the 23d Infantry. Each of the four regiments deployed in column of battalions. Thus, the attack was deeply echeloned. On the Americans’ outer flanks French units would attack in support, but the Indianhead Division was the main effort.

Opting for surprise over any attempts to destroy the German defences, the artillery preparation was scheduled for only 5 minutes of very intensive fire, what was called at the time a ‘hurricane bombardment’. The lighter guns would then switch to fire a creeping barrage to screen the advancing infantry, while the heavies would lay a heavy standing barrage on the enemy’s main defensive line along the ridge, timed to lift as the assaulting troops arrived. At that point the fire plan then departed drastically from AEF doctrine, which called for the 75mm light guns to be dispersed piecemeal among the infantry units as accompanying artillery to support what was hoped would be a rapid forward advance from the initial objective – supposed to be the start of the ever–elusive open warfare. Lejeune, on the other hand, ordered selected gun battalions to start deploying forward early as whole firing units, so they could get into position to support with massed and coordinated fire a deliberate advance of the infantry after the latter had consolidated on the initial objective. This was another element of the set–piece approach, rather than the immediate exploitation that Pershing so ardently believed was the solution to the problem of trench warfare.

Salient

The American barrage opened up at 5.50am on 3 October. Supported by the French 167th Division on his right, Ely’s troops reached the top of the ridge by 8.40am. Once on the initial objective, they provided supporting fire to the Marines on their left. Nivelle’s brigade, which had a longer distance to advance, also reached its objective on schedule, despite the fact that the French unit on its left stalled, exposing the Marines’ flank. While the 6th Marines continued to push forward, the lead battalion of the supporting 5th Marines immediately deployed a strong force supported by machine guns, tanks, and 37mm infantry guns against the German machine–gun emplacements that were firing from the French side of the boundary. That quick action helped the 6th Marines to maintain their forward momentum.

Once Lejeune’s troops consolidated on their initial objectives and an adequate number of guns had been brought up, the Americans sent patrols forward. Then the 5th Marines passed through the 6th, the 23rd Infantry passed through the 9th, and the new lead echelons continued the advance preceded by another intense creeping barrage and supported by standing barrages on the flanks. By late afternoon the Americans had taken all their final objectives, having driven a 3–mile deep salient into the German lines. But the French 167th Division on the right and especially the 22nd Division on the left lagged far behind, exposing the American flanks to enfilading fire from German artillery and machine guns.

Second Day

The French commanders heaped praise on the 2nd Division, but they also demanded immediate exploitation. XXI Corps commander, General Stanislaus Naulin, ordered Lejeune to continue advancing to the town of Machault, which was a good 6 miles from the present American lines. Citing his dangerously exposed flanks, Lejeune refused until the French units closed up. He also wanted to give all of his artillery the necessary time to get as far forward as possible, and he demanded a robust resupply of ammunition for his guns. Naulin insisted, but Lejeune stood his ground, also pointing out that Machault was far too deep an objective to take with a single attack. Naulin finally backed down and agreed to let Lejeune conduct a shallower attack the next day.

On 4 October the 5th Marines advanced to the high ground about a mile south of St Etienne, all the while taking heavy casualties from the German flanking fire. On the right, however, the attack of the 23rd Infantry stalled, and Ely finally had to order his brigade to fall back to its starting positions. That left the 4th Marine Brigade dangerously exposed on both flanks. The Germans launched a relentless series of counterattacks and the Americans suffered far heavier casualties that day than they had on the first day of the operation. The deadliest fire came from strong German machine–gun positions to the immediate west of Blanc Mont, where the French were still lagging far behind. That night Bowley’s gunners pounded those positions relentlessly. On the morning of 5 October, the American guns fired an intense hour–long preparation, and then the Marines attacked behind a creeping barrage. Without losing a single man, they took the position and captured 200 German troops and 75 machine guns. Ely’s brigade, however, was still held up by intense German fire from its open right flank.

Protest

Naulin continued to demand that the Americans push forward regardless of the costs, but Lejeune refused to be bullied into mounting unsupported attacks. Lejeune moved all his artillery as far forward as possible. Starting at 5:30am on 6 October, Bowley’s guns fired a one–hour preparation and then each brigade moved out under a creeping barrage. Within three hours both American brigades had closed up to the south side of the St Etienne–Orfeuil Road.

The 2nd Division had accomplished its mission and more, but by that point it was exhausted. Lejeune was given operational control of the 36thDivision’s 71st Infantry Brigade, and during the night of 6–7 October the raw troops relieved the veterans in the front line. The 142nd Infantry Regiment relieved the 4th Marine Brigade, and the 141st Infantry Regiment relieved the 3rd Infantry Brigade. Knowing full well, however, that the replacements would need all the stiffening they could get, Lejeune left one battalion from each brigade and most of his machine guns and mortars in place. Lejeune also wanted to give the new troops a couple of days of training in the front lines. Naulin, making no allowances for green troops, ordered a full–scale attack on the morning of 8 October. Lejeune protested; Naulin insisted. The defenders anticipated the attack. The Germans all along the sector were already preparing to withdraw north to the Aisne. The only place they were continuing to counterattack was against the 2nd Division, with spoiling actions to cover the withdrawal preparations. The defenders were ready for a fight on 8 October.

As soon as the American guns started their initial preparation fire that morning, the German artillery opened up with a massive counter–preparation, firing toxic gas rounds mixed with HE. Coordination between the 141st and 142nd Infantry broke down immediately, and the main attack stalled in the centre after only about 500m. The two veteran 2nd Division battalions, which were on the American outer flanks, did manage to continue advancing. The Marine battalion on the left flank passed through St Etienne and dug in on the north side of the town, which allowed the 142nd Infantry to move up. Meanwhile, the 2nd Division’s veteran infantry battalion on the right launched a fierce counter–attack into the German flank and pushed the American line several hundred metres north of the St Etienne–Orfeuil Road. The fighting ebbed and flowed throughout the remainder of the day, with the 71st Infantry Brigade troops suffering more than 1,300 casualties on 8 October alone.

The Americans spent the following day consolidating the line and moving ammunition and supplies up. On the night of 9–10 October, the 36th Division’s 72nd Infantry Brigade moved forward and relieved the remainder of the 2nd Division’s troops that were still in the line. On the morning of 10 October the Germans began their general withdrawal to the Aisne. The Siegfried Line in Champagne was broken, although for the time being it still held in the American sector between the Argonne and the Meuse. During the Battle for Blanc Mont Ridge the 2nd Division had suffered 4,821 casualties, roughly half the total losses at Belleau Wood; but in seven days of fighting as opposed to twenty. But also, as opposed to Belleau Wood, Blanc Mont was fought with intensive artillery support and skilful combined arms warfare. Strategically, Blanc Mont was the 2nd Division’s most significant contribution to winning the war.

After the war the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) constructed a number of impressive monuments on many of the AEF’s battlefields, including at Blanc Mont. They remain, beautifully maintained, more that 100 years after those battles were fought. Yet the monument at Blanc Mont today is also a rather lonely place. Most visitors, both American and non–American, tend to concentrate on the monuments in the Marne sector, or on those between the Argonne and the Meuse. A visitor to Blanc Mont today might well have the entire place to him or herself but it is important that a visit be made nonetheless for it is a battle that deserves to be better remembered.

After the war the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) constructed a number of impressive monuments on many of the AEF’s battlefields, including at Blanc Mont. They remain, beautifully maintained, more that 100 years after those battles were fought. Yet the monument at Blanc Mont today is also a rather lonely place. Most visitors, both American and non–American, tend to concentrate on the monuments in the Marne sector, or on those between the Argonne and the Meuse. A visitor to Blanc Mont today might well have the entire place to him or herself but it is important that a visit be made nonetheless for it is a battle that deserves to be better remembered.

Major General David T Zabecki served in Vietnam as an enlisted rifleman in the 47th Infantry in 1967–68. In 2003 he served in Israel as the senior security advisor on the US Coordinating and Monitoring Mission, charged with managing the Roadmap to Peace in the Middle East initiative. In 2004 he commanded all US troops in support of the D–Day, Market– Garden, and Battle of the Bulge 60th anniversary observances. In 2012 he held the Shifrin Distinguished Chair in Military History at the US Naval Academy. He holds a PhD in Military History from Britain’s Royal Military College of Science, Cranfield University. He is the author of the recently published The Generals’ War: Operational Level Command on the Western Front