The War To End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The War To End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I

The War to End All Wars, The American Military Experience in World War I by Edward M. Coffman

This work, first published in 1968, has been reprinted in 1998. The following is a transcript of interviews which took place in May and June 1998, between Dr Coffman and Paul Guthrie, exploring the elements identified by Dr. Coffman as crucial to understanding of the American Great War experience and contribution. The book consists of 430 pages, a number of maps, an essay on sources and an index. It is available from the University Press of Kentucky.

This article was first published in the Western Front Association magazine 'Stand To!' no.54 January 1999. This magazine, and its sister publication 'Bulletin' form part of a member's subscription. 'The War to End All Wars' was reviewed by Bob Wyatt for 'Stand To!' no.36 Winter 1992 edition.

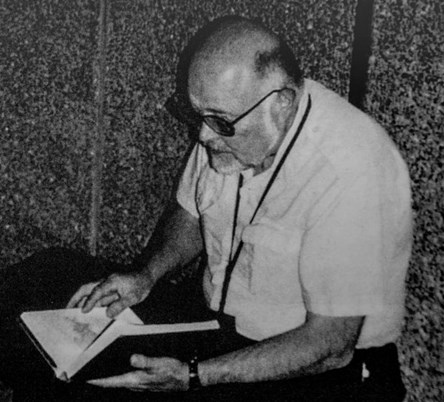

Dr. Edward Coffman

Guthrie: Dr Coffman, what's the basic theme of your book?

Coffman: Well, the title really spells it out. To War to End all Wars represents the great expectations, the idealism that the Americans had when they went into the warl. Then the subtitle really spells out exactly what the book is about. It is about the American military experience in World War I. I'm fully aware of the great contributions and tremendous involvement of the Allies, particularly the British and the French. But, I am not dealing with that. I'm really concentrating on the American experience, and this is the experience all the way from pre-war planning, to experience in the training camp, medical problems, flu epidemic, things of that sort, on up to the combat. When I discuss the campaign, I start with the top – what the generals were trying to do, what they thought they were going to do, and then carry down to a company grade officer or a soldier who is in the trenches and is saying just about 100 yards around him. In order to do that, I not only went through a lot of published material – all I could get my hands on – unit histories, the memoirs and monographs, then I went to the archives and looked up records.

Guthrie: Speaking of United States National archives?

Coffman: Yes, the National Archives, and looked at records there. And finally I went around and talked with veterans. For example, I interviewed the first American ace about what it was like for a guy actually up there flying. I interviewed a Marine was gassed at Belleau Wood. I talked with several senior officers, including several generals in a couple of the division chiefs of staff. I interviewed extensively one of Pershing’s key staff offices, his G-4 was in charge of coordination. I also interviewed people who were really down there in the midst of the fight. For example, from the first American attack in Cantigny in late May, 1918. I interviewed the commander of the regiment and two company commanders. So I've really got into their experiences – what they saw and what they thought about what was going on. I tried to make it as top to bottom as I could.

Guthrie: While you're speaking of your methodology, in case some of the readers of this interview are historians themselves, it might be useful to know a bit about your sources.

Coffman: There are lots of unit histories and those are very interesting.

Guthrie: Are all sources listed in the sources portion of the book?

Coffman: Yes. I didn't use footnotes, but I have an essay on sources where I mention these books. These unit history vary on how good they are, but even the bad ones have a lot of good raw material – reports, letters, and the like. At the time I wrote this book in 1967, I had never visited the Western Front. But the American Battles Monument Commission published a detailed guide, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe (1938), complete with extra maps, and I relied on those maps to get an idea of what was going on, where people were and so on. When I actually went over there in 1990, I was pleased that I didn't see anything much different on the train then I had learnt from these maps. I had been at infantry officer and I had extensive training in map reading at the Infantry School at Fort Benning. That really helped me out great deal when I started writing about the campaign.

Guthrie: Your book thoroughly discusses the lack of preparedness of the United States Army. Since the sinking of the Lusitania in May of 1915, it was obvious that the United States was likely to become involved in the war. We did not actually declare war until April 1917. How do you account for that lack of preparedness when we had so much warning of the likelihood of entry into the war?

Coffman: The lack of preparation was in keeping with the American idea that 1 million men would spring to arms overnight. The Americans had always been suspicious of a standing army – a regular Army. So our regular Army was really minuscule compared to the other major powers. In addition to the anti-military ethos, it costs money to maintain an army. Even at the time it looked like we might get involved of the sinking of the Lusitania, Americans just didn't want to build up the armed forces. There was, however, a preparedness movement. Some people went to training camps, but you have to remember that in 1916 Wilson ran on a campaign slogan that he kept us out of the war, and the presumption was that he would continue to do so. So there was never much hard core preparation for the war. As a result, we still had a very small army of 127,000 when we went to war in April, 1917.

National Guard Units

Guthrie: There were state units called National Guard units, many of which were called up before we entered the war to serve under Pershing in the Mexican Punitive Expedition.

Coffman: Actually they're called upon to serve on the board. George Fugate was down there.

Guthrie: He is a 104-year-old World War I veteran, alert and competent still living in Lexington, Kentucky.

Coffman: That's right. He was first sergeant of the company in the 2nd Kentucky.

Guthrie: It seems to me from reading your book and others, there was bias in the regular army against these National Guard units and that there was some preference to draft fresh men in preference to using these units. Is that true?

Coffman: Yes. The bias was for two reasons. Regulars very obviously considered themselves, and they were, better trained. They were professional soldiers. The state units were citizen soldiers who met periodically for training, including a week or two in the summer. The other reason was that the War Department didn't have that much control over these people. They were state troops and federal government – the regular army – couldn't tell them to go from point A to point B. However, the federal government could call them up.

Guthrie: Federalised them?

Coffman: They could federalised them, and this is what happened in the Mexican troubles in 1916. Pershing took only regulars across the border. The National Guard, some 120,000 or so, were called up to guard the border. Up to then, these units were state troops, so if the federal government call them up, the man had the option not to go, so when the federal government called up these troops, they would concentrate, and then each individual had the choice of going on active service. Understandably, the War Department wanted more control over citizen soldiers, hence the advocated a federal reserve so that men could not be subject to state control.

Guthrie: Dr Coffman, at the time you started writing this book in the 1960s, how many other serious historians at major universities in this country were doing research on the military aspects of the war, as opposed to the diplomatic aftermath and the consequences of the war following in the rest of the century?

Coffman: The short answer is few. Harvey De Weerd had written a dissertation on supply of artillery shells, and he was writing book which came out at approximately the same time as mine called President Wilson Fights His War. The title is misleading. It is really history of the entire war, 1914–1918. He doesn't discuss that black soldiers. He gives maybe a paragraph or less to the air war. He hardly deals with the navy either, and he doesn't go into detail about what was really happening to people. There was also a professor at the University of Cincinnati, David Beaver, would just written a book on the Secretary of War Newton Baker. I had written a book before this on the American chief of staff, Peyton C. March. Also David Trask, who had been at the University of Nebraska and went to the State University of New York in Stony Brook, had written a book about United States and the Supreme War Council.

Black Troops

Guthrie: You mentioned the back troops, referred to at period, among people who did not refer to them in disparaging terms, as negroes, what is your opinion of the treatment, including the fairest of the valuation in the performance negro troops?

Coffman: I go into this in some detail in the book. Later on there would be a very good book written about them called The Unknown Soldiers, by Arthur F. Burdeau and Florette Henri, which goes into this in much more detail. Most blacks were drafted. Only a few blacks were in the guard. The most single famous black unit was the 15th New York, of which it is said that it had more days up front than any other American unit. These units, most of them, had white offices.

Guthrie: Were there any black officers, including any black West Point graduates during that period?

Coffman: Yes, there were. At that point there were three regular army black line officers in the army officer corps of 5000. One of them, Charles Young, Lexington, was a West Pointer and a lieutenant colonel. All three had excellent service. Benjamin O. Davis, who was a captain when we went to war, became the first black general in the American Army in 1940. During World War I, however, there was an effort to keep them out of it. Young was retired and Davies spent the war in the Philippines. None of the four black regular regiments got to France. The draftee units went and some of the National Guard units. They were formed into two divisions. One division, the 92nd, had a considerable number of black officers who had gone to the officer training camps in 1917 or had been NCO’s in the regular army. Most of the company grade officers, lieutenants and captains were black and a few were field grade in the 92nd. The 93rd never existed as a division.

The four infantry regiments served throughout the war with the French. It was simply attached to the French, wore French helmets, and had the French rations. They even had the French rifles, and they did very good service. They were decorated with the Croix de Guerre. Pershing, who got his name "Black Jack" because of service with the 10th cavalry, one of the black regular regiments, believed, as did virtually all whites, that black troops are good only if led by white officers. There was an incident in the Meuse Argonne where a black regiment with a 92nd version had a difficult time. They were told they were going to attack a lightly defended area that hadn't been fortified much, which was later found not to be true. This incident was always set as an example of the blacks don't fight well. The regiment did have real problems there, but I don't think you could say that was unique. Many of the white regiments had problems also. But that regiment’s experience in the Argonne was used for years, into the 1950s, to malign blacks as combat troops.

US Navy

Guthrie: You also discuss the role of the United States Navy. Was the navy able to have an immediate impact? Why was the navy so much better prepared for the army?

Coffman: The Navy was better prepared than the army for one very good reason. If you look at what the army does and you look at what the navy does in peacetime, more than 50% of what the navy does is sailing ships. That's what they do in peace or war – it's the same thing. They are apt to be at any given time more ready because they have people to know how to operate the ships. The army is not fighting anyone until they actually get into war. As soon as we got in the war we sent a flotilla of six destroyers over there to join the British and the anti-submarine campaign, which was operating out of Ireland. Incidentally, I interviewed one of the officers, a lieutenant on one of these destroyers who was one of the first man over there. I used his experiences to explain what happened. The navy did a very good job on the war. Like the army and the marine corps, they expanded tremendously. There was also a huge shipbuilding campaign, but these were not warships particularly, they were supply ships.

American Entry

Guthrie: Do you think the Germans did not believe the United States would enter the war after they resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, or that they believed that we would enter the war but have no appreciable effect on it, as they had thought about the British in 1914?

Coffman: I think the Germans assumed we would enter the war when they made the decision for unrestricted submarine warfare. Wilson had made declaration that if you do this, we are apt to go to war. But various German officers had visited and had seen the American army. I once went through a file while working on this book about this. In 1912, the American adjutant general, who is in charge of the military attachés, sent out a questionnaire to attachés over in European countries to the effect, “What does your country think about the American army?” Their responses were interesting. Most of them said that their host nation didn't think about the American army. They did not consider it as a factor. The Germans had been over here and seen the mobilisation in 1911 when we organise the division at Fort Sam Huston and they were not impressed.

Guthrie: What was the purpose of that mobilisation?

Coffman: That was another scare about Mexico. Hence the army organise this manoeuvre division in 1911. The Germans couldn't believe it. It was shocked because there was no respect for the military in that country and most of the soldiers are foreigners. They thought that it was almost like the Foreign Legion. They couldn't believe how small and inconsequential the American army was and they couldn’t conceive of this small group mobilising enough people I'm getting them across the Atlantic to make a difference in the war. But they knew that we were advancing loans and we were sending war material or manufacturing war material that the Allies were using. They thought that if the Americans go to war they will simply expand that effort. After all, the concept and the submarine war was to cut off the traffic in the Atlantic going to the Allies, and they assumed they could do it. And, of course, they came very near doing it. The great story of the wae is the development to the convoy system which eventually defeated the submarine threat.

General MacArthur

Guthrie: Dr Coffman, I know that you wrote another major book about the American military and interviewed a rather well-known person in the course of the research. Can you tell me about that?

Coffman: Yes. When I was working on a biography of the American Chief of Staff in 1918, Peyton C. March, The Hilt of the Sword (1966), I interviewed Douglas MacArthur, who had been very close to March, and I'm one of only three historians who interviewed him. He was very enthusiastic about March. He considered him, perhaps, the greatest chief of staff. Of course, you wouldn't expect MacArthur to see George Marshall was the greatest chief of staff. I think Marshall was the greatest chief of staff, but MacArthur was very enthusiastic about March. MacArthur talked about the war period.

Guthrie: When was this interview with general profit?

Coffman: 1960, at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City.

Guthrie: How long an interview was it?

Coffman: Two hours.

Guthrie: Do you remember what he had to tell you about his own experience in the Great War?

Coffman: The most dramatic thing he said was about a picture taken in the summer of 1918. In it he stands with a riding crop on the steps of the stone building. He explained that there had been a conference right at that time. He was chief of staff of the 42nd Infantry Division. The corps commander, Hunter Liggett, had come down checking on the Division. He talked to MacArthur about the brigade commanders – one in particular. MacArthur was very pensive when he said that this general always thought that MacArthur had criticised him, but instead MacArthur claimed that he tried to put the best face you could on the general’s work. He also talked about the scene of the picture. The photographer took the picture never saw it because he was killed not long after that.

The American Contribution

Guthrie: What is your opinion of the American military contribution on the Western Front?

Coffman: I think what the American contribution to the war was in providing the sheer weight of manpower at a time when the Allies, the French and the British, had been able to hold the Western Front stalemate for three years even though they outnumbered the Germans.

In 1918 the Germans transferred A large number of troops from the Eastern Front that had closed out, then the Germans had the numerical superiority on the Western Front and the Germans started making breakthroughs with the great offences on the Western Front. That shear strength of American manpower made a big difference. I write about this in the book. For example, after the last advanced made by the German army, in the second Battle of the Marne, they launched that offensive and, of course, it was stopped cold partly by the French, but also by several American divisions. Guthrie: You're talking about Chateau-Thierry?

Coffman: Yes, July, 1918. After that the Germans are pulling back or they are on the defensive. Now Ludendorff, of course, says his black day was August 8th when he realised, now we don't have people to bring up there. The point I try to make in this book is that the tide had turned after Soissons when the Americans and French make the counter attack in mid-July. That is one of the major things because the Americans are there in great numbers. By the end of the war they have as much front, I think, more than…

Guthrie: Your book says a tiny bit more than the British.

Coffman: That's right. Still less than the French, and, of course, if they had gone into 1919, they would've had more. Pershing’s last surviving staff officer, George vanHorn Moseley, told me in an interview that Pershing, in talking about the war, said at a certain point we would have more of the front than anyone else. We will have more people over here, and at that time I will be the supreme commander. And he was probably right.

Guthrie: Didn't he mean that Foch was going to be cashiered?

Coffman: No. He meant that he (Pershing) would be, as the national representative of the country making the most effort, the one calling the shots rather than Foch. Now Foch, of course, never had the power of a supreme commander in World War II such as Eisenhower, MacArthur or Mountbatten. They could order people to do things. Actually, they hacked to take into consideration the nationalities and it was a very touchy political thing. All Foch could do was make recommendations. Any of those national commanders, including Petain, the French commander, if he didn’t want to do it, he couldn’t say I'm not going to do it because I don't really think that's really fair to France I’ll take it up with the French government. Pershing could do it with the Americans. Haig could do it with the British. But I think the fact that the Americans were there in such great numbers was putting so much pressure on the Germans. I mean, my goodness, the French were just hanging in there by their teeth after the failure of the offensive in early 1917. Incidentally, there was an American corps, the American Second Corps with the. I think it was the New York National Guard, 27th division, and a southern National Guard – I think the 31st.

Guthrie: By the time of the Germans really started getting rolled back by August 8, 1918, it seems Haig and the British were making more rapid progress than the Americans and French. Do you believe they had a better army, or they had more favourable terrain?

Coffman: A bit of both. Once the Americans got in the Meuse Argonne that was a very difficult sector as far as terrain was concerned. There is no question about it. I pored over the maps and later went over the Meuse Argonne carefully, and there is no question about the difficulties. The plan was that they would make a breakthrough the first day, which they didn't do, and they struggled up there for weeks, they had a tremendous problem. Part of the problem was they really didn't have experienced commanders, staff and troops. Many of those units that went in today where in the first action. It did strike me, as I was going through all of this material, that near the end, by the time you get into late October, the officers and men really know what they are doing. In mid-October Hunter Liggett, one of my heroes, took over the First Army. He calms the army now gets ready for the final part of the offensive. Among other things, Liggett is the one American commander I know of who really used gas affectively.

Guthrie: What's this artillery or the old cannister method?

Coffman: Artillery. What he did was use gas to suppress a force. A German unit was up in this woodland and it took them out of action. As a rule, there is a fear of using gas offensive because you'd have to go into it. But he gassed those poor guys and moved on past them. Liggett took charge of the army, calmed things down, got them re-organised and in shape to go ahead.

Guthrie: Who was Liggett?

Coffman: He was a lieutenant general and commander of the First Army. He had been a corps commander. Up to mid-October Pershing was the commander in chief of the AEF, as well as the first army commander. Now, in effect, what this meant was Hugh Drum, the 38-year-old chief of staff of First Army, was running it most of the time, as General MacArthur told me, because Pershing was doing various other things. Once Liggett came in, he took charge and settled the thing down and got them going. Now the American argument, and there is some validity to that, is that they were fighting a battle of attrition in the Meuse Argonne. The Germans had to hold that area because, if we made a breakthrough, we would break their main supply route for the entire Western Front and, therefore, they had to hold. There is some validity to that, but I think the main thing about the Germans is they could see the handwriting on the wall, they certainly suffered a great deal from the British blockade. The German army was getting in a bind, so I think this pressure on them and the knowledge that a great many more Americans were coming was too much.

I tell two stories in the book, one came from the man was the American Embassy representative checking on the welfare of the German prisoners of war – Lee Meriwether. Mr Meriwether, when I interviewed him he was 95 or so, was at one of the ports where POWs were stevedores. One of these big convoys was coming in as the doughboys streamed down gangplanks. This German asked Meriwether if those were Americans. Meriwether said ‘yes’. The POW asked if this happens very often, and Meriwether said it happens every day. The German said ‘My God in Heaven’.

And I also tell the story in the book. George Seldes, a war correspondent in World War I, was the first American to get an interview with Hindenburg after the war. He asked Hindenburg, “Who won the War?’ Hindenburg said, ‘The American infantry’. Now what he meant was not that the American infantry was so well trained or they were so well officered, but that there were a lot of them. They were coming over and there was a lot more. It was simply that vast pool of replacements that were available.

Guthrie: You mentioned that some American said, at Meuse Argonne in particular, we were fighting a battle of attrition, meaning we were killing a lot of Germans. Wasn't the original intention to make a breakthrough which we could not make?

Coffman: Yes. It's a rationalisation. But I went through a lot of this correspondence. Fox Connor was Pershing’s G-3. There is the correspondence and the Pershing papers and I forget what else I ran into, but I am sure they were rationalising it.

Guthrie: Is it true that we did not learn lessons that were there to be learnt? By the time we entered the war in April 1917, and certainly by the time we got into some serious combat by June 1918, it was very clear that this was a war of machine guns, barbed wire and artillery. Yet, apparently in looking at ourselves in some kind of backwards frontiersman image, we believed that we could go over there and win battles with massive and accurate rifle fire and develop open warfare. What do you think counts for that what it all true that we could? Coffman: Well, we certainly couldn't. I think Pershing wanted to put his individual stamp on the AEF and make sure these people with different and build up their morale and all of that. In the summer of 1917 Summerall got into trouble when he was over there on an advisory group and they were talking about how much artillery they were going to have, and he advocated a much larger artillery component. Later, this artillery was certainly needed.

Guthrie: Who was Summerall?

Coffman: C.P. Summerall later was a corps commander. He later commanded the First Division and Fifth Corps. He was famous for being an artillery commander. Summerall really a character. In the Boxer Rebellion he was a battery commander. When they came to a walled city, Summerall went out with chalk and marked on the gate of the city where he wanted his artillery to shoot, then ran back. That is the type of guy he was. He was very famous at The Citadel. (After he retired, he was President of The Citadel, a military college in South Carolina.)

Guthrie: Do you think that we were taking inordinate casualties even by Great Wall standards?

Coffman: No, I don't think so. Look at the tremendous casualties the British took at Passchendaele. Look at the French. They also did. Look at the Germans. It wasn't until they came in with new Von Hutier tactics, that there was a sensible way of breaking up this type of line.

Guthrie: Are you talking about the Michael offensive in 1918?

Coffman: Yes, later. The idea was that instead of attacking and ordering troops over the top after lengthy bombardments, to have a short and quick bombardment and then attack. If they were going to jump off at 6:00, the barrage started at 5:59, and it's a creeping barrage that moves right ahead of them and instead of attacking in long lines, big units, they were attacking in small combat groups. They were ordered to bypass strong points and exploit the weak points. And, of course, if you do that, you start making breakthroughs. However, there is a defence against it. The defence does not fortified the front so much and have it sort of thin and have them develop their attack before you can have a second line or something that will stop them.

End of Interview

IMAGE: With thanks to the Pritzker Military Museum & Library.