A Century Old 'Thank you' : Frederick Clark KIA 21 March 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Century Old 'Thank you' : Frederick Clark KIA 21 March 1918

The events of World War I have burned themselves into the national consciousness - especially during the past four years, when every battle, every incident, every death has had its 100th anniversary. With the centenary of the end of the war in sight, many are the stories that have been told and are waiting to be told. This is just one.

My father [writes Roy Bailey], Harry Bailey, and my two uncles, Fred Bailey and Frederick Percy Clark, all served on the Western Front. Harry was an Army Service Corps driver while both uncles were in the 8th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment. My maternal uncle Frederick Clark did not survive the war; he was killed near Saint Quentin in the big German offensive of March 1918, and has no known grave.

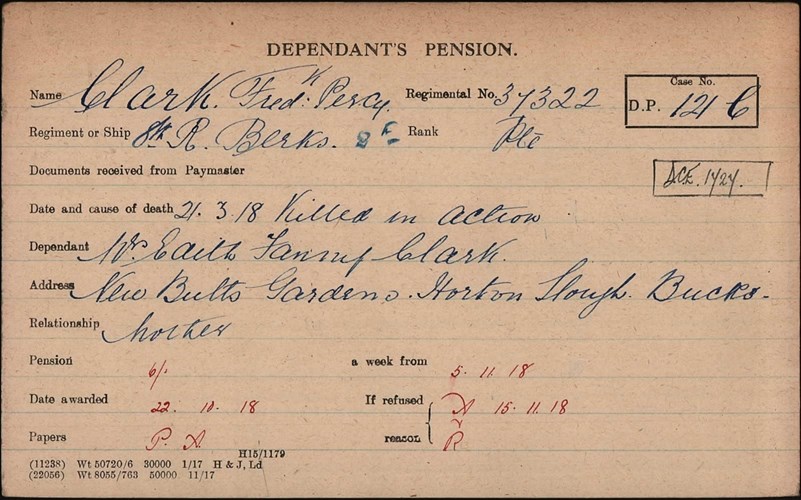

Above: The Pension Record Card for Roy's 'other' uncle, Frederick Clark

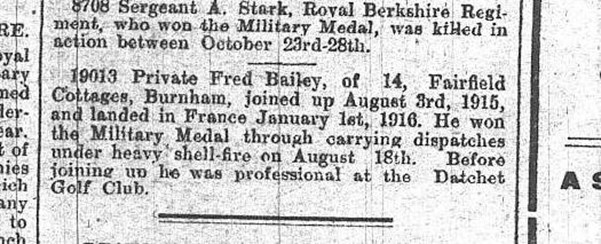

Uncle Fred Bailey, on the other hand, had a good war (if such a thing is possible), winning the Military Medal and Bar.

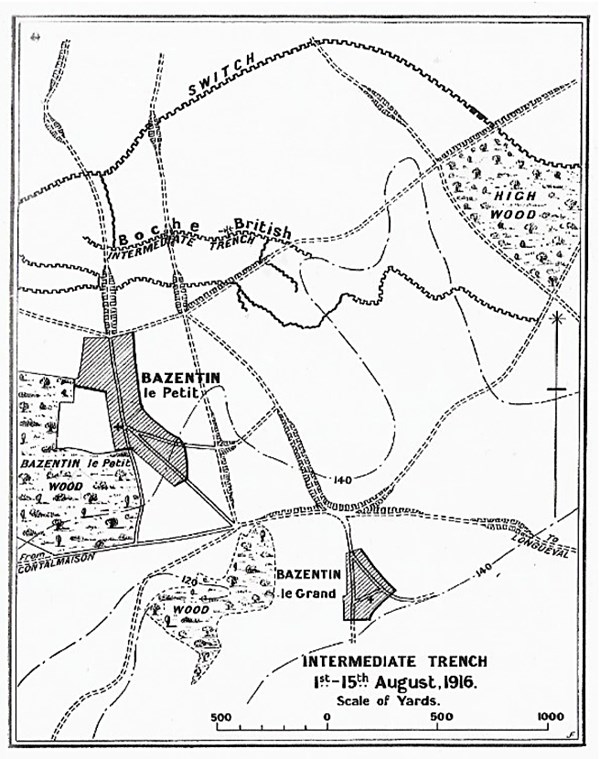

Fred (his baptismal name) joined the Royal Berkshire Regiment in August 1915 at the age of 23 and was posted to the 8th battalion in January 1916. Since his service records were destroyed by German bombing in the Second World War we have very few details of his activities, but he sprang to notice during the Battle of the Somme. The battalion War Diary records that, on 18 August 1916, they were at Bazentin-le-Petit, near Albert, about to attack the German positions. ‘At 12 noon the heavy artillery commenced a bombardment of the 'INTERMEDIATE LINE' unfortunately one gun was firing short and its shells fell on our own front line just at the time when the relief was taking place. The effect of these shells was that many of our men were buried and the trench was so badly blown in that intercommunication between one portion of the trench and another was impossible.’

Above: Intermediate Line on the Somme

Fred was a runner, charged with carrying messages around the battalion, and in this case he did it while being shot at by the enemy and shelled by his own side. For this he was awarded the Military Medal.

Above: Fred Bailey

In his memoir, War Letters to a Wife, Captain Roland Feilding lavishes praise on such runners, so the award must have been justified. It caused quite a sensation in Fred’s native village of Burnham, near Slough, where his parents received many congratulatory messages and the managers of his old school there resolved to record the honour in their minutes.

In July 1917 the 8th Royal Berkshires were confined to a secret camp near Dunkirk, training for an amphibious assault (which never took place) against the German-held coast of Belgium to the east, when a new Commanding Officer was appointed. He was Lt Col Robert Dewing DSO, a former Royal Engineers captain who had been singled out as good commander material, bumped up two ranks, and put in command of the battalion. He proved to be one of the best and most popular COs that the battalion ever had.

Above: Lt Col Robert Dewing DSO

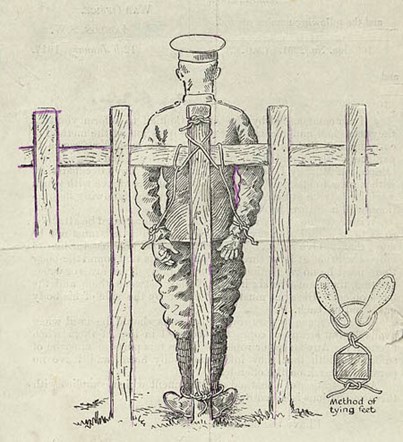

In his memoir Confessions of a Private, Frank Gray, who had refused a commission and later became an unconventional Liberal MP and world traveller, praises Dewing, stating that his ‘whole attitude was that of calling for and not demanding comradeship. He won what he asked’. Gray also remarks on Dewing’s hatred of petty offences being brought to his notice, and his refusal to allow the degrading No. 1 Field Punishment within his battalion.

Above: No. 1 Field Punishment

Gray even dedicated his memoir to Dewing, stating that he ‘possessed a fine knowledge of men, was humane, kind and courageous, and so remained to the end’.

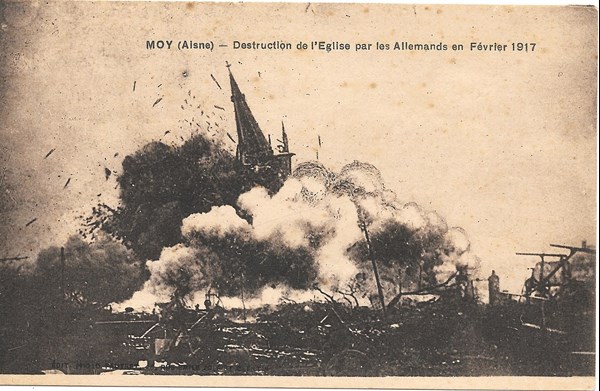

This then was the man who was in command of the 8th Royal Berkshires when they were overrun by the attacking Germans on 21 March 1918 near Moÿ de l’Aisne and pushed back 40 miles.

Above and below: Moÿ de l’Aisne then and now... and a plaque to the action fought in Guinguette Wood which was unveiled on 21 March 2018

Robert Dewing handled the dire situation well, and was put in charge of the composite battalion to which the three regiments of the brigade had been reduced. By the beginning of April the 8th Bn had been more or less reorganised as such and were in the front line near Gentelles, a few miles east of Amiens. Fred Bailey had by now become the Colonel’s batman or soldier-servant; an appointment that may have been inspired by Dewing’s discovery that Fred had been the professional at Datchet Golf Club, near Windsor, before the war. Dewing was a keen golfer and cricketer, so this would have been a bond between them.

Above: Berkshire Chronicle 1 December 1916

At 10 am on 4 April the battalion was ordered to take up a position at Hangard Wood, east of Gentelles. At 5pm the enemy were seen to be approaching the battalion’s position.

Above: An aerial of Hangard Wood today. The orange dot is approximately where Col Dewing was killed.

The War Diary reports:

‘Heavy Lewis Gun and rifle fire was opened upon the enemy, By this fire very severe casualties were inflicted upon them, as the enemy, at that stage, were attacking in force and advancing in waves. At this juncture of the Battle the Commanding Officer LT COLONEL R.E. DEWING DSO, was wounded, necessitating his leaving Batt Head Qrs. Whilst doing so, assisted by 19013 PTE F. BAILEY MM, he was shot through the head, being killed instantaneously. The very able and gallant manner in which Col Dewing was conducting the operation in progress, and the tactful and fine way that he commanded and personally led the Battalion during the period 21st-27th March commended itself to and was a great stimulus for all ranks’.

Some reports state that Fred was also wounded but not seriously; apparently by a bullet hitting a tin of bully beef in his knapsack. He was later seen helping 2/Lt Wallis to safety. For his conduct that day he was awarded a Bar to his Military Medal, which was presented at a ceremony on 3 May by the Corps Commander, Lt General Sir Richard Butler, K.C.M.G, C.B.

Above: Lt General Sir Richard Butler, K.C.M.G, C.B

I was not able to find out anything more about this incident, and nothing exists concerning this in Fred’s family archives. However, in June 2015 I subscribed to The Great War Forum, an online archive of everything to do with World War I populated by hundreds of subscribers posting questions and answers. As a part of my research into a book about the exploits of my father and uncles during the war, I posted number of queries, and received some useful information, but nothing further about Fred Bailey. Then in May of this year a posting appeared addressed to me from a woman subscriber which read:

‘Having just joined the forum I’m so glad to have found here a relative of 19013 Pte Fred Bailey. He was with my grandfather, Lieut Col Robert Dewing RE, when he was killed near Villers-Bretonneux on 4 April 1918. I have a letter from Fred Bailey to my grandmother Ruby telling her how it happened (I can send you a copy), and before her own death in the flu epidemic a year later she tried to contact him again, but without success’.

E-mail contact revealed the correspondent to be Mrs Sally Jeffery who lives in Hackney and is writing a book about her grandfather. As promised, she sent me (among a number of other documents) a scan of my uncle’s letter and a transcript – and fascinating reading it makes, too.

There had already been a considerable amount of correspondence with Ruby Dewing before Fred Bailey became involved. She would probably have received an official telegram informing her of her husband’s death, and on 11 April the Divisional commander, Major-General Higginson, wrote to her. He was unable to tell her very much other than what he had gleaned from official reports, and neither was the battalion’s second-in-command, Major Morony, who had remained in Gentelles. On 12 April Morony wrote suggesting that she write to 2/Lt Wallis, ‘who was with your husband to the last’, and was now in hospital back in England.

On 4 May Morony sent Wallis’s address to Ruby, and she and Dewing’s sister Phoebe both wrote to Wallis asking for details. Although he doesn’t mention my uncle in either reply, somehow Ruby learned of his part and wrote to him.

‘ Dear Madam,’ Fred replied on 24 May, ‘I have just received your letter of 17 May enquiring about Col Dewing. I am very sorry you have not been informed before as our Padre said he would write and tell you full particulars, that is why I never wrote myself’. Obviously the Padre had neglected his duties.

Fred goes on to describe the traumatic events of that day; how the ground was quickly overrun by the enemy so that it was impossible to recover the body of the Colonel and other officers, and how when the area was again in British hands a few days later no bodies could be found; the assumption being that the Germans had buried them.

Above: Lt Col Robert Edward Dewing. He is commemorated on the Pozieres Memorial.

‘I am sure it must have been a great blow to you when you heard the sad news of his death’, Fred concluded. ‘It was a great loss to the Batt as he was the finest officer we have ever had and he was loved by all his officers and men, and if it had not been for his fine leadership and bravery there would not have been any of us left at the present moment. So please accept mine and the rest of the Batt (sic) deepest sympathy in your great loss, I cannot describe how much we have missed him’.

Above: a photo postcard sent by Fred Bailey and dated 13 November 1916. Fred is the right-hand figure.

Sally and I met at the Youth Hostel at Rotherhithe in September to talk about our mutual interest and to exchange documents and photos. She believes that her grandmother wanted to meet Fred in person to thank him for his actions and get more details of her husband’s death. She gave birth to her second daughter in October 1918, and, with the end of the war, may have assumed that Fred was now back in England. In January she again wrote to Morony asking for Fred’s address, but as Morony had been demobilised for some time he advised her to write to Infantry Records Office in Warwick, which she did.

They replied in March, ‘I cannot trace Pte. Bailey under the number given by you; no. 12015 is held by another man’.

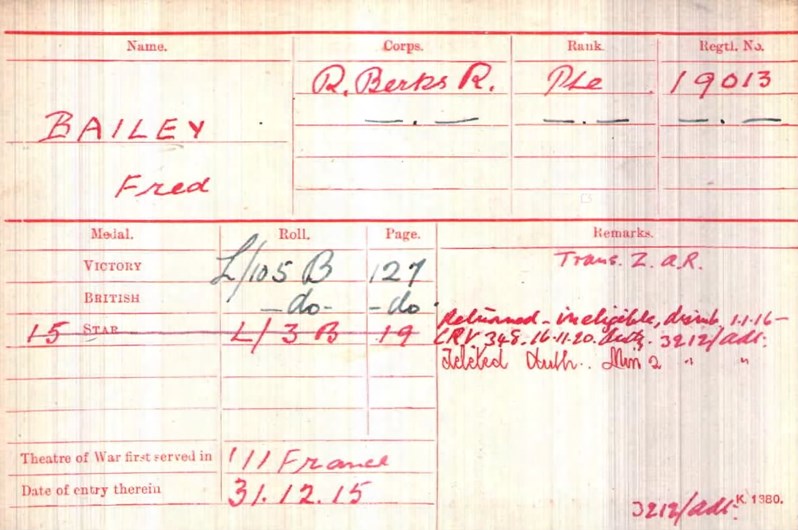

Above: Fred Bailey's Medal Index Card showing the correct regimental number

Sally believes that her grandmother had difficulty in reading Fred’s regimental number, and mistook the 9 for a 2 and the 3 for a 5 – a look at the original suggests it was an easy mistake to make – and somehow the mistake was compounded to produce entirely the wrong number.

By then the 8th Battalion had been disbanded and Fred was somewhere in limbo. He had gone on 14 days leave to the UK on 3 February 1919, then apparently returned to France. He was finally demobbed on 4 July, but there is no record of where he spent those last weeks and months.

Ruby Dewing died of influenza on 21 April 1919, with her wish unfulfilled. It is sad that my uncle was never able to receive the personal thanks of the widow of the man who had died in his arms, but fate and time have produced some compensation. As we sat drinking coffee in the lounge of the Youth Hostel, Sally said that, on behalf of her grandmother, she wanted to thank me, on behalf of my uncle, for his letter – a century late.

Article by Roy Bailey