Friday the 13th in the 13th month of the war: The sinking of the Royal Edward

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Friday the 13th in the 13th month of the war: The sinking of the Royal Edward

It was a Friday morning in August – the 13th month of the war - and perhaps some of the more superstitious troops on board His Majesty’s Transport (HMT) Royal Edward were concerned that it was also Friday the 13th.[1]

With it being August, the Eastern Mediterranean was hot and the morning lifeboat drill had just been completed. The soldiers – reinforcements for Gallipoli, mostly bound for the 29th Division – would have been keen to get into the open air before the heat of the day became too much. But first they had to go back to their cabins to stow away the lifebelts. It was at that point that a torpedo hit the ship.

This is the story of one of the greatest losses of life in a single incident in the Great War. It also reveals, possibly for the first time, how hundreds of men were left to drown by other ships that were in the vicinity.

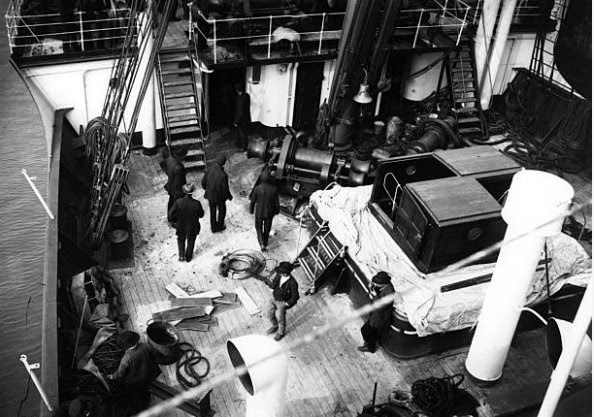

Above: Royal Edward alongside at Avonmouth

The Gallipoli campaign was, by the summer of 1915, stalling. The landings in April had failed in their primary objective of enabling the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force - under General Sir Iain Hamilton - to clear away the Turkish shore batteries, so as to allow to Royal Navy to pass through the narrows.

Further attacks had been made on the peninsula but wounds and illness had taken their toll on the troops. As a result reinforcements were desperately needed. Reinforcements meant troopships were required, and as a result a number of transatlantic liners were requisitioned for transporting these men from the UK out to the eastern Mediterranean. Cunard’s Aquitania and Mauretania as well as White Star’s Olympic were among those vessels employed in this role. However, the potential for loss of life was significant should any be intercepted by German submarines. The loss just a few weeks earlier – in May 1915 – of the Lusitania was an example of what the human toll could be should such a ship be sunk.

For the transport of reinforcements to Gallipoli one of the requisitioned vessels was the Royal Edward. The ship was owned by the Toronto-based ‘Canadian Northern Steamship Company’, a subsidiary of the Canadian Northern Railway. The Royal Edward was 526 feet in length and at 11,000 Gross Registered Tonnage was about one-third the size (using that metric) of the Lusitania (32,000 GRT).

Above: H.M.T. Royal Edward at Devonport, 14 October 1914. Credit: Library & Archives Canada

Troopship and the Crew

Normally – when operating prior to the war – the Royal Edward had capacity for some 1,114 passengers (over half of these being third class) but in order to maximize the troop capacity she was – in August 1915 – loaded to 125% of capacity, and was carrying about 1,400 soldiers. These, in addition to her 220 crew, meant she was likely to have been fairly cramped for those on board.[2]

On 30 July 1915 HMT Royal Edward departed Devenport (Plymouth) for the Eastern Mediterranean. The intention was for her to head to massive harbour at Mudros on the Island of Lemnos where the men would be transshipped or sent ashore before completing the last leg of their journey to the Gallipoli peninsula – some 50 miles to the north east of the island.

On board the Royal Edward was – not surprisingly – large numbers of men who were destined for infantry battalions. These were to reinforce the 29th Division which had been used numerous times since taking a prominent part in the initial landings. There were two large drafts destined for 1/Essex and 2/Hampshires; smaller drafts for the 1/Border, 1/KOSB, 1/Lancashire Fusiliers and 2/South Wales Borderers were also onboard.

In addition, on the Royal Edward were a significant number of RAMC personnel, being reinforcements for the 54th (East Anglian) Division’s and the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division’s Field Ambulances – many of the East Lancashire RAMC troops being from Burnley.

Another notable contingent numbering over 200 men were from the Army Service Corps’ 18th Labour Company. Approximately half of these men were from Cornwall. Probably about fifty of these men were between 40 and 49 years old, at least another nine were over 50 and one (Francis Bryan) was aged 66 according to the CWGC.[3]

The Royal Edward was commanded by Peter Wotton who had – until 1913 – been Chief Officer of the Royal Edward’s sister ship, the Royal George.

Two of the crew were just 16 years old – George Wines (an Officer’s Steward) and Ernest Bannister (an Assistant Engineer's Steward). Many of the crew were from a variety of different countries. More than a dozen were from Malta, at least five were from Greece and four Swedes were on board. There were also men from Finland, Norway, Spain, USA, Canada and even Peru.

Above: Athanassios Dedes was from Piraeus, Greece (source: WFA Pension Records). For some reason he is not recorded by the CWGC.

German Submarine Operations

Despite being, before the war, part of the ‘Triple Alliance’ with Germany and Austro-Hungary, Italy had not joined her pre-war partners on the outbreak of the conflict and chose to remain neutral. A secret treaty was signed on 26 April 1915 (coincidentally the day after the initial landings on Gallipoli) in which Italy undertook to declare war against her former Allies and join with Britain and France. War was declared by Italy on Austro-Hungary a month later, but - significantly – she delayed declaring war on Germany for another year.[4]

As the French and British navies were operating in the Mediterranean with impunity (the Turkish Navy was bottled up in the Black Sea and the Austrian Navy was largely confined to the Adriatic) Germany felt that the best way to hit back against the Gallipoli campaign at sea was via submarine warfare.

The German type UB I submarine was a class of small coastal u-boats designed to operate in the shallow seas off Belgium. They could be quickly constructed and because they were small (only 92 feet in length) were able to be shipped by rail to be re-assembled at their port of operation. They did not have a good reputation. Despite being small they were underpowered and slow (one commander compared his vessel to a sewing machine).[5] These submarines did not have enough power to chase surface ships and were further hampered by having poor underwater endurance. They only had two torpedoes so were severely limited in the number of vessels they could attack on any patrol.

Because of Italy’s failure to declare on Germany, but wanting to support her ally Austria, Germany decided to operate submarines in the Mediterranean under the flag of the Austro-Hungarian navy (Kaiserliche und Königliche Kriegsmarine or K.u.K. Kriegsmarine). This was the best way – the Germans believed – of disrupting reinforcements going to the Gallipoli peninsula.

German submarine UB-14 was one of four of these small u-boats that were transferred to the Austro-Hungarian navy, and after being transported overland, arrived at Pola on 12 June and was re-assembled.[6] The vessel was given the Austro-Hungarian designation of SM U-26.

On 1 July 1915, the submarine joined the Pola Flotilla under the command of 25 year old Oberleutnant zur See Heino von Heimburg and (with her all-German crew) went out on her first patrol.

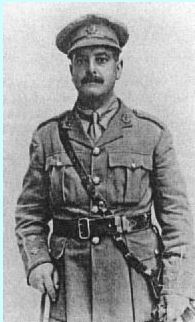

Above: Oberleutnant zur See Heino von Heimburg

On the night of 6/7 July, Italian armored cruisers that had recently been deployed to Venice undertook a reconnaissance off Pola. In the early hours of the 7th, von Heimburg was just 20 nautical miles off Venice. At dawn the German submarine captain came across the Italian armoured cruiser Amalfi and fired a torpedo.

Amalfi immediately began listing to port and, after initial damage control efforts proved ineffective, her captain ordered the ship to be abandoned. The cruiser sank less than half an hour after she was torpedoed. Fortunately loss of life was not large, with only 67 men being lost.

As a result of Amalfi's sinking, her sister ship Pisa and the other armoured cruisers at Venice rarely ventured out of port for most of the next year and were eventually transferred to Valona in April 1916. This was an early and significant victory for the German submarine operations.

Meanwhile, Enver Pasha and other Turkish leaders had requested their German and Austrian allies to send submarines to the Dardanelles to help sink the British and French warships that were attacking the Gallipoli peninsula. The Germans responded by dispatching von Heimburg’s UB-14. The submarine’s limited range meant that she had to be towed by an Austrian destroyer as far as the Turkish port of Bodrum.

Above: SM UB-14 on the surface of the Black Sea. The submarine's crew is gathered around the tower. Of note is the German flag

En-route UB-14's engine and gyrocompass broke down while nearing Crete, leaving the submarine dead in the water for a spell. However, temporary repairs by the crew enabled the boat to arrive in Bodrum on 24 July. A repair party was dispatched from Constantinople who had to make their way by train and then by camel to reach Bodrum. After repair, UB-14 was ready to resume her journey by 13 August.

Above: The route from Pola to Bodrum

“Tell[ing] mother we're going out east” (interview with Harold Barrow, RAMC)

The Royal Edward, after leaving Devenport on 30 July, headed for the Mediterranean, stopping briefly at Valletta (Malta) for coal. Continuing eastwards, Royal Edward arrived in Alexandria, some 850 nautical miles from Valletta, on 11 August.

Above: HMT Star of Victoria moored at the wharf at Alexandria, Egypt. Equipment and men of the Australian 1st Divisional Ammunition Column have just been unloaded. (AWM)

At Alexandria Captain (acting Major) Cuthbert Bromley came aboard the Royal Edward. He had stormed ashore at the famous ‘Lancashire Landing’ action on 25 April and had been awarded the VC (by ballot) for this action. Bromley had been wounded in the knee three days after the landing and evacuated to Egypt. He was now heading back to Gallipoli and was probably looking forward to a pleasant voyage on the Royal Edward.

The Royal Edward stopped less than a day in Alexandria, departing on 12 August. She headed north-west for the last leg of her voyage to Gallipoli. All being well she would arrive at Lemnos two days later.

Daybreak on Friday 13 August found Royal Edward north of Crete between the Cyclades and Dodecanese island groups. Ominously, she was now only about 100 miles west of the Turkish port of Bodrum. This was to be the last dawn that many of her crew and troops on board would behold.

UB 14 attacks

After leaving Bodrum UB-14 had passed the Greek island of Kos and was close to the island of Kandeloussa (30 to 40 miles south west of Bodrum) when von Heimburg observed several potential targets. The first ship was the British ship Soudan, heading south to Alexandria from Gallipoli. Von Heimburg, identified her as a hospital ship, and so allowed Soudan to continue without making an attack.

Above: Above: The Hospital Ship ‘Soudan’ leaving Malta.

The next vessel spotted was the Royal Edward. Von Heimburg launched one of his two torpedoes from about a mile away and hit Royal Edward in the stern, on the port side, just forward of the mainmast. Royal Edward was mortally wounded.

Above: Although from the starboard, this shows the main mast where the torpedo hit.

An account from Sgt George Bollinger, Number 10/1024 Wellington Regiment, NZEF

A remarkable diary entry written by Sergeant George Bollinger of the NZEF details what happened. Bollinger served with the Hawkes Bay Company of the Wellington Infantry Regiment. He had been recuperating in the New Zealand General Hospital No 2 with a case of Gastritis. He was onboard the SS Alnwick Castle.

Bollinger – in his diary - describes how the SS Alnwick Castle had a ‘submarine guard’ of 60 men.

“Friday 13 August. How often does the average trooper thank God his life has been spared. I am afraid the 600 men on board the troopship ‘Alnwick Castle’ found themselves in that position today. Early this morning the ‘Royal Edward’ a magnificent passenger liner with from 2500 to 3000 British troops on board overtook us.[7] She was lying at the same wharf as us in Alexandria and evidently steamed out the same night. This morning she steamed alongside us about six or seven miles out on the starboard side.

Above: Alnwick Castle was built in 1901 by Wm. Beardmore & Co. at Glasgow with a tonnage of 5893grt, a length of 400ft 5in, a beam of 50ft 2in and a service speed of 14 knots.

Above: Another view of the Alnwick Castle

“At 10 o’clock practically everyone was at the rails looking at her and remarking what a fine ship she was. At about this time a Hospital Ship passed quite close to her on the way to Alexandria.[8] Suddenly some of the men said they heard an explosion and all eyes were cast on the ‘Royal Edward’. She was undoubtedly settling on her stern and within three minutes she had stood right up and went completely under.

“She sank straight down from this position. Only one thought flashed across our mind. She had been torpedoed. Our course was changed, a full complement of stokers put on and we made for our lives at the best this good ship could give. We all went below and put on our lifebelts then going aft to await our turn. The Hospital ship put back to the scene of the disaster but I am afraid there would not be many souls to save. If the Royal Edward had not overtaken us this morning we undoubtedly would have stopped that torpedo.”

Above: The 'flag' is the position where Royal Edward was when hit. Highlighted by a red cross is Bodrum. Also shown (top) is Gallipoli and (bottom) Alexandria

An account from Sgt Alexander Fraser, Number 16867 Border Regiment (Liddle Collection)

Alexander Fraser was interviewed by Peter Liddle in 1976. Fraser was 18 years old and had lied about his age to join the Border Regiment. He was helping to lead a draft destined for the 1st Battalion in Gallipoli. This draft comprised three sergeants and 74 men. It would appear that this draft was proportionately the worst hit, with 60 of the 74 being killed.

Despite his youth he was one of the sergeants. Fraser was in a second class cabin with three other sergeants (presumably including at least one from a draft for another regiment). His cabin was on the deck (rather than in the bowels of the ship), a fact that was to save his life as he did not have to move far to retrieve his lifebelt.

“We had a submarine guard up on the top deck [comprising] about 100 armed men … my recollection is that a small, what we would call on the Clyde a ‘puffer’, was coming toward us [he is almost certainly talking about the Alnwick Castle] and it was, oh, probably quarter of a mile away and it sailed on and the submarine which had been screened behind it was there, and we were a sitting duck. He just plunged his torpedo and it went straight into the engine room. Just one torpedo.”

An account from Harold Barrow Number 327, RAMC

Harold Barrow (1894 -1987) was in the East Lancashire Field Ambulance. Harold – who was aged 21 at the time – is one of two survivors whose oral testimony will be extensively used, both of these being recordings preserved by the IWM.

Harold tells us…

“[It was a] very lovely day. Lovely day, very hot. Yes. Calm, sea, beautiful. It was about quarter past nine in the morning when everybody was getting ready for the major parade of the day. I was in the cabin, just getting my kit on, when one of my cabin friends, a chap named Simpson rushed in.”[9]

“I heard a bump. I thought, ‘oh, this fella's running on one of these islands or something’. He [Ernest Simpson] said, ‘We've been hit, Harold’. [I] scooted about, took all my tunic and stuff off, grabbed my life belt and made as quickly as I could to where the boat I was detailed to.

“The lifeboat was along the promenade deck, down into the well deck, up onto the boat deck…. By the time I got there and was taking my boots off, I took one boot off, and the the ship went under. But the sight was, all these soldiers streaming up from the lower decks, coming into the welldeck…. I'm sure they would be all washed back to where they came from.

Above: The forward well deck of Royal Edward.

“Anyway, as I say, I was taking my boots off, and I was engulfed in water …Fortunately, I held on to my life belt. And I must have been perhaps unconscious or something or other for a moment or two.”

“I swam away from it and there was one chap, he looked in trouble. Anyway, I held him up for a bit, but he was dead….And I went on and helped another fellow… I gathered one or two bits of wreckage about. I said ‘Can you swim?’ He said ‘No, I can't swim’. I said ‘Well, hang on to this’. I said ‘Don't panic. Just hang on’. So I left him to it, and I swam to an upturned boat, and clambered on that. And then one or two other fellas came along and they clambered on, and it righted itself, this boat.

“There was a topi there, you know, a pith helmet. We bailed out with what we had, and got it going and collected one or two men, including a sailor, who seemed to know more about it than we did. And we got going, and I think we got about thirty odd in it.

“One incident when we went rowing about, we came across an upturned boat and somebody said, I wonder if anybody's under it. We turned it right, and there was a fella under it. He was resting on the thwarts as they call them, and I must admit his face was bruised because there was a blooming old tin or something, just ebbing and flowing against him. But he hung on, he was alright.

An account from Arthur Bonney, number 19347, South Wales Borderers

A similar experience is recounted by Arthur Bonney (1895 -1987).

Before the war Arthur lived in Hackney. He was part of the reinforcements destined for the 2/South Wales Borderers. Arthur is the other survivor whose oral testimony is preserved by the IWM.

Arthur recounted:

“Well, when it was hit, it exploded inside, and the decks…they all came up and they began to part. I climbed up the outside of the boat, up to the top deck, on the outside.

He then explains what happened to his friends….

“They all ran down for their life belts. So I said to them ‘You haven't got much time to go down there’ because you could see the boat was parted [he then explains it was breaking in two].

“When I got up on the deck I saw this officer, a young lieutenant, he was the only one by the lifeboat, he said to me, ‘You don't stand much chance without a life belt’. It had started to tilt then and the lifeboats well, they all went upside down…nothing could be launched.

“It sank in four minutes…. Just gave you time to climb up there and when I was talking to him all the seats were rolling down the deck and we saw one half [of the Royal Edward] go down.

“By the time I got in the water there was two halves, and I watched them go down, and I was swimming as hard as I could, thinking I might go down with that boat. But I saw the last of it go down, and then I saw all the debris on the other side of it and upturned life boats and chaps and everybody in the water.

“I swam and swam, thinking I was going to be drawn down with it… I could see other people jumping off, with lifebelts on. And when I got in the water, there was any amount of them floating away with their heads underwater …we heard afterwards they got broken necks, jumping from the deck.

“I could swim... I thought, ‘well, something's bound to come along’. But the boat had passed us in the morning was the hospital ship ‘Sudan’. That was the boat that came back and picked us up. But then a lot of other boats by then were picking other chaps up, you know.

Arthur managed to climb on board an up-turned life boat.

“There was about twenty on it…Every now and again it'd turn over and, and they'd have to clamber back on. And those chaps were singing ‘It's a Long Way to Tipperary’…. Every now and again you'd see a couple of bodies float by, you know.”

Sgt Alexander Fraser of 1/Border Regiment again:

(The following is merged from his oral testimony and a letter in his hand writing. Both give the same details, but in slightly different words).

“About noon, a small steamer came in amongst us. Another of these like a coasting puffer and he shouted down. Well, he sort of fiddled his way in amongst us and shouted down, what has happened here? And some of our chaps shouted back what it was, it was the Royal Edward. ….He rang his engine room telegraph full steam ahead and of course, the chaps in the water shouted curses at him. What about picking us up? He said, ‘I couldn’t pick you lot up. I couldn’t possibly. Anyway I am full of high explosive for Lemnos. If that bugger comes back we will all go up’. He said that he’d send a signal.”

(Peter Liddle, the interviewer, asked if he actually heard this conversation)

“No I saw it though. I saw the small ship. Those of who were still afloat were spread. We were scattered.”

Arthur Bonney of the 2/SWB again

Asked how long it was before he was rescued, Arthur said:

“I think that was about four hours. The, Sudan turned and came back, got a signal…on its way to Alexandria and turned back and picks us up.

Above: Hospital Ship 'Soudan'

“I only had a pair of trousers on. I'd stripped my boots off and coat on board. You could see [the Soudan] from a long way off…you could see the steam, then you could see the funnels, and then you could see the boat.”

Arthur was asked about his friends:

“I don't know. I never saw them again. No, none, of them survived. …They never had time to get down, I shouldn't think. “

Arthur explained out of the 130 in his draft (in the 2/South Wales Borderers) only seven made it to the Hospital Ship Soudan. However, this is (understandably) inaccurate. There seems to be around 56 men of the 2/SWB who were killed in the sinking.

Arthur was asked about the officer from the Royal Edward who had spoken to him.

“Oh yes, well, I went into Alexandria and walking down this street, and who should come along was this young officer I saw on the boat!

“He said ‘I never thought of ever seeing you again’ and then he told me about how he felt he'd just got time to get this waistcoat on that he had and lifejacket and he went down with the boat. Well, he said he never thought he was ever coming to the top. And he said, ‘I reckon I was traveling at a hundred miles an hour’.”

Harold Barrow of the East Lancashire Field Ambulance RAMC continues his story:

The IWM interviewer says “I was going to ask you, because this is remarkable, that you actually had a set of photographs of the shipwreck. Could you tell me about how you came to acquire these?”

“I don't know how I did, except it was that friend of mine, Billy Cullen. He was the man [I met] when I was rescued. This chap came walking along the deck and I recognised him pretty well at once. It was this Billy Cullen, a boy older than I was, he'd be perhaps 22 or 23 Billy, who was a serving in the Merchant Navy, and was something like an assistant purser on this hospital ship.

“Of course, we greeted each other, we were surprised. He took me down into his cabin, but I was alright, there was nothing wrong with me. He gave me a drink of brandy and I went to sleep, I should think, for a couple of hours. Then he said, well, when we get to Alex, we'll have a night out. Which we did!

“He fixed me up with a sailor’s uniform, white peeked hat and double breaster. We just strolled off the, off the Sudan.... And went to Alexandria, had a bit of a meal, and I sent this cable home to Mother. And that was it.”

The IWM interviewer asks: “You were telling me about the photographs, how Billy Cullen came into this.”

“Well, I never could remember where they came from. And it would be when I came home from the army when I was discharged in March 1919, I'd rather fancied these photographs where at home and I think there must have been a splendid photographer on this boat that rescued us, and Billy Cullen had told them about me and they were probably sent to my home.”

The IWM interviewer says: “And of course you have kindly donated those photographs to the Imperial War Museum.”

Asked how long he was in the boat before he was picked up by the rescue ship, Harold said:

Oh, I should think within two or three hours, I should think. One or two of the fellas were, you know, a bit hysterical when we dragged them into the boat. For myself, I was quite calm, really.

He was asked if he knew which direction to row in:

No, I don't think so. We just rowed amongst the wreckage, picking people up who were hanging on to spars and oddments and things like that.

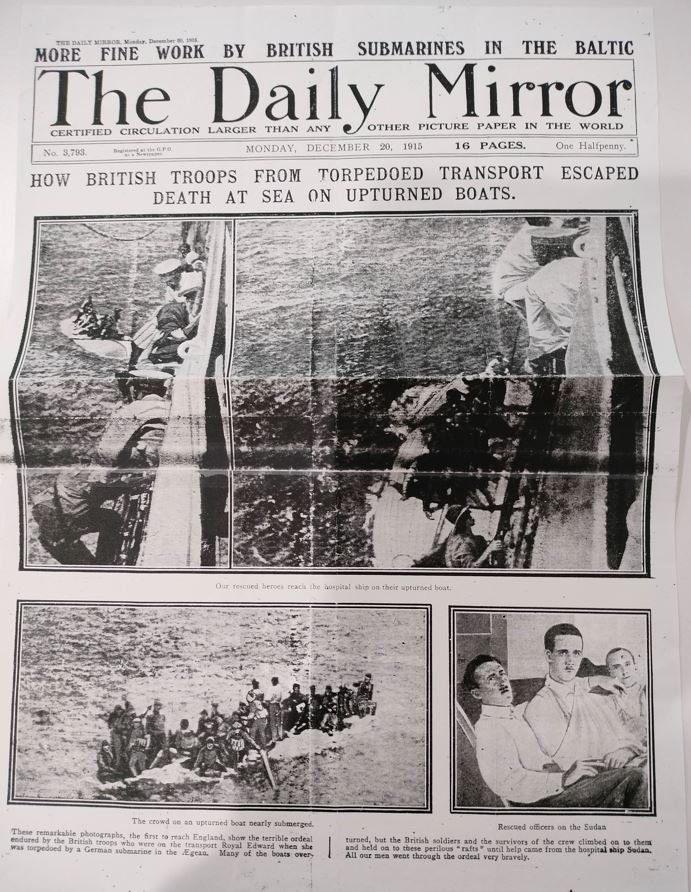

Above: Two boats of the Royal Edward as sighted by the Soudan

Above: Waiting to be taken off. Survivors of HMT Royal Edward on an upturned boat

Harold was asked if he was still picking people up at the end of those two hours:

“No, I think we were just, we'd just about come to the end of it all. Probably after an hour perhaps, really. We [were] just rowing about to see if there was anybody. We didn't pick any [bodies] up. I didn't think there'd be a lot [of bodies], except those that floated up, I'd expect they would float up. There was a tremendous lot that'd go down with the boat and never come up, I should think. I don't think there was a great lot rescued.

“It was calm. I asked this sailor fella, ‘Where's the nearest land?’ ‘Crete’ [he answered] I said ‘How long will it take us to get there?’ I think he said ‘Well about a fortnight!!!’

He was then asked about the moment he was rescued by the Hospital Ship the Soudan:

“No, I never saw it [the Soudan] until it came up [to] us. We must have been looking the other way, I should think. And so we rode to it, and just clambered up the side, and, I think they might have put a boat or two down to go round and pick up any oddments.

Above: Survivors of Royal Edward coming on board H. Ship Soudan. Nearly all lifeboats were upturned.

Above: Boat from Hospital Ship “Soudan” looking for survivors

“You'll get a better idea when you see these photographs of the people on, the Soudan that had been rescued.”

Above: Survivors climbing rope ladder from upturned boat.

Above: Survivors of the Royal Edward in hospital gowns.

An account of the rescue comes from Arthur Sanders (RAMC) who was on board the Hospital Ship ‘Soudan’

Friday August 13th 1915 at about 9.30am we passed H.M.T. “Royal Edward” and at 9.45 am we received a message by wireless to say that she had been torpedoed, so we put back to her assistance arriving on the scene about 11 am where we remained until 3 pm picking up the survivors.

What a scene it was there were boats right way, wrong way up rafts, wreckage of all kinds, barrels, hatch covers, etc, some even clinging to oars, some swimming. Poor mortals they had not much chance to prepare to leave their ship as she went down well inside five minutes.

In one case we got about seven or eight men off a boat which had floated keel uppermost and when we got them alongside, they said they were two men underneath, we thought their wits had left them as they seemed scared. Well we got a line attached and with the help of a crane lifted one end of the boat, which was a steel one by the way, up a little out of the water, and sure enough we got two poor R.A.M.C. chaps from under. They had managed to get a little air through the plug hole in the bottom to keep them alive. They could not have lasted much longer for the poor fellows were almost collapsed when got aboard which was a difficult job.

We only lost two by death after bringing them on board. One we had performed artificial respiration on for over an hour, but it was too late.

About 3pm. we continued on our way to Alexandria with all speed. It will be noticed it was a Friday, 13th day of the 13th month of the War.[10]

The statement by Arthur Sanders stating that only two men died aboard the Soudan is supported by an inspection of the cemetery register for Alexandria (Chatby) Military and War Memorial Cemetery and the WFA’s Pension Record Cards. Buried at Alexandria are two men both of whom ‘died at sea’. One is Private Joseph Woodcherry (SS/14008) and the other was Charles Henry Norman (SS/13849) both of the 18th Labour Company, ASC.

Above: Pension Record Card of Charles Norman

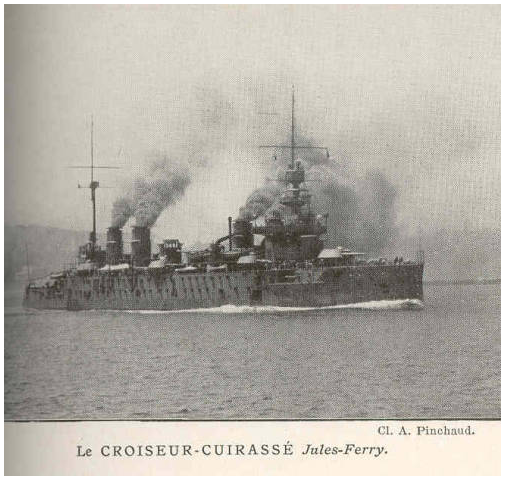

Besides the Soudan, other ships eventually arrived, including the French armoured cruiser the Jules Ferry

Above: French cruiser, the Jules Ferry

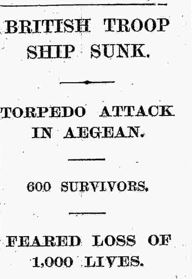

Newspapers pick up the story

Despite the sinking having an impact on morale, it seems there was no news blackout. News reached home and Canadian newspapers ran major headlines. The Times detailed, on 18 August ‘British Troop Ship Sunk. Torpedo Attack in Aegean. 600 Survivors. Feared loss of 1,000 lives.’

In Canada, the news was splashed on the front page of the Victoria Daily Times (the significance of this is that the Royal Edward was Canadian owned).

Local newspapers also speculated about losses, with details unclear about who may have left the ship at Alexandria. Such stories were obviously reported in places where the losses were localized, such as in Cornwall. This in the Cornish Guardian on 20 August 1915.

Some months later, the images that Harold Barrow referred to made it into the Daily Mirror.

Fatalities among the 1/Lancs Fus, 1/KOSB and 1/Essex

Meanwhile, letters were sent home which also made their way into newspapers. This is the extract of a letter from Private R Burton, of the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers. It is likely that this was the smallest contingent of the infantry reinforcements as ‘only’28 men from the draft of men to this battalion were lost

“Just a few lines to let you know that I am one of the saved. The ship went down in five minutes. I had just time to go into a cabin and get a lifebelt and jump overboard. When she went down the suction of the ship drew me in towards her, but the explosion blew us clean out of the water away from the sunken ship. I was among hundreds of struggling soldiers battling for dear life.

“I swam about and floated until I came across a kind of milk-can which I clung to for about an hour, treading the water until it began to fill, so I had to abandon it. I swam about until I came across some wreckage. I managed to get hold of three planks, deck planks, and clung to these for dear life until picked up by the lifeboat of a hospital ship that came to our rescue, after being five hours in the water. It was blessing that the water was warm, or we would have perished...”[11]

One of those killed in the draft destined for the KOSB was a former professional footballer, William Lee Mcallister Miller. Sergeant Miller’s wife, who lived in Dumfries received a letter which read:

“It is my painful duty to inform you that in the list of survivors from the transport Royal Edward lately lost in the Aegean Sea, which has to-day been received from the War Office, the name of No. 16337 Sergeant W.L. Miller, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, who is believed to have been on board, is not included. If any further information is received it will be immediately communicated to you.

“Prior to enlisting Sergeant Miller was a picture framer. He was had played for the Dumfries Hibernians and afterwards played as a professional for St. Bernard’s and Grimsby Town. Having returned to Dumfries he frequently officiated as a referee at the local matches.”

(Dumfries and Galloway Standard: September 1, 1915) [12]

The KOSB draft lost 59 men in the sinking.

A ‘last postcard’ arrived at the home of Edward Tuttle’s parents. Edward was in a draft for the 1/Essex. This was one of the largest drafts of men on the Royal Edward and consequently a large number of men from this unit were to be drowned. A total of three officers and 174 men from this draft were killed in the sinking, Edward Tuttle being among this number

The postcard, with a postmark 'Devonport' and dated 31st July 1915, 9.45am and with half-penny stamp was addressed to Mrs E. Tuttle, Norwich Road, Mattishall, East Dereham, Norfolk . The card was probably delivered some days before news of the sinking. The postcard read: ‘Dear Father & Mother, Am sending a photo of ship have only an hour longer here as we sail tonight at 8 o/c Friday, Much love Ted Don't expect letter just yet. Farewell’. [13]

Above: Edward James Tuttle

2/Hampshires: Heaviest losses and four pairs of brothers

Although the losses to the 1/Essex were heavy, those in the draft for the 2/Hants were even worse – the deaths among this draft totalled 212 and included three officers who had been transferred to from the 9th Somerset Light Infantry. These were 2/Lt James Foster aged 24 who had only been married in four months earlier (his wife was to give birth to their daughter in April 1916), 2/Lt Richard Spurway (aged 25) and Lt Edward Thompson (aged 36).

Above: 2/Lt Richard Spurway and Lt Edward Thompson

Remarkably, within this draft were four pairs of brothers who were all killed:

Herbert and George Toogood were possibly quite close, as suggested by their consecutive army numbers.

Victor (aged 17) and Edwin (aged 23) Hillary both seem to have added a couple of years to their ages as the CWGC record them as 19 and 25 respectively.

Walter and Albert (Bertie) Light of 5 New Road, West End, Southampton.

Also from the ‘West End’ area of Southampton came Frederick and George Curtis. Tragically, a third Curtis brother had been killed just three days prior to Frederick and George’s death. Leslie - aged 17 – and serving in the 10/Hants - was killed on 10 August 1915.

East Anglia Field Ambulance

Other drafts also suffered grievously. The 54th (1st/1st East Anglian) Casualty Clearing Station and Field Ambulance lost nearly 70 officers and men. Harry Hall was one of the lucky ones.

In a letter to his mother, posted in Port Said and printed in the Kettering Leader of 17 September 1915, Harry described the sinking and his rescue.

“I had a terrible experience, she sank in four minutes. I stayed on the ship till the water came up to the second deck and then I jumped into the sea. When she finally sank we were all drawn under by the suction and I thought I was never coming up again. But at last I did and saw a sight that I shall never forget. All sign of the ship was gone, but the sea was covered with wreckage and men yelling like mad.

As soon as I came up I grabbed hold of a door that came floating by. I lay on this for about half an hour, when I was picked up by one of the ship’s collapsible boats that had got off somehow.”

Others of the 54th CCS and Field Ambulance were not so lucky. The Commanding Officer of the 54th CCS and the most senior officer on board the Royal Edward to lose his life was Lt Col John Henry Dauber who was aged 56.

Above: John Henry Dauber

Another senior officer in the 54th CCS was also lost. James Mowat served as a Surgeon in the Royal Navy from 1894 and retired in May 1914, after 20 years service. He was recalled for active service on the 4th August 1914 and was appointed Principal Medical Officer on H.M.S. Hermes. However, following the sinking of this cruiser in October 1914, he was invalided out of the Navy. Due to the shortage of military doctors, James volunteered and joined the East Anglican Casualty Clearing Station, being granted the rank of Major.

Above: James Mowat

One of the other ranks from the 54th Casualty Clearing Station draft was Private Arthur Haslop aged 27. Arthur (a domestic gardener) was the son of Henry John and Ellen Joanna Haslop of 47 Alpha Terrace, Trumpington, Cambridge.

Above: Arthur Haslop

East Lancashire Field Ambulance

Other significant RAMC fatalities were incurred in the East Lancashire Field Ambulance which lost 61 officers and men. Captain Charles Bertam Marshall was the senior officer lost in this unit.

A high proportion of men from this unit were from Burnley with nearly 40 men either from or born in the town lost. The local newspaper reported two weeks later:

Though it is a fortnight this morning that the troopship the Royal Edward was torpedoed in the Aegean Sea, on its way to the Dardanelles, no official list of survivors and victims has yet been issued. It was estimated that about 600 men of a total of 1,500 on board were saved, the troops consisting mainly, according to the Admiralty notification of reinforcements for the 29th Division and detachments of the R.A.M.C. The latter was known to include a batch of about 70 men from this district from the 2/1st and 2/2nd East Lancashire Field Ambulance (Territorials), and the fate of these men has occasioned much anxiety in Burnley and Padiham whence the men were chiefly recruited. [14]

Those lost included 17 year old Private George Altham.

Above: George Altham

George was the son of Alfred Edwin and Annie Altham, of 28 Cromwell Street, Stoneyholme, Burnley.

But George was – despite being 17 –not the youngest from the unit or the town to be killed. Nelson Kilburn was just 16 years old.

Nelson was living with his sister, Mrs Dodgson of 8 Railway Terrace, Padiham, when he enlisted. He was a member of the Padiham Ambulance Brigade and was employed by Jackson’s, furniture dealers in Accrington.

Above: Nelson Kilburn

Another teenager who was also lost was 19 year old Frank Whalley

Above: Frank Whalley

Cornwall’s 18th Labour Company, ASC

Another very significant draft of men was heading for the Army Service Corps’ 18th Labour Company. Approximately 124 men from this unit were lost when the Royal Edward was sunk, including two officers, Lieutenants Edward Burtt and William Lund.

Above: Edward Burtt

Lieutenant Edward ‘Teddy’ Burtt was 46 years old and unmarried, from Eden Bridge, Kent. William Bullen Lund was a 50 year old stockbroker who was married with two children.

A description of Lt. Lund's end is given by a private in his Company:

“About ten minutes after the ship went down I was clinging to a raft and all at once I saw someone appear above water. I got on the raft and caught hold of Lieutenant Lund by the shirt and pulled him on to the raft as well as I could.... I kept him on the raft with just his legs hanging in the water for more than an hour, but I'm sorry to say he never spoke after... A wicked sea capsized the raft and I lost him altogether. I've heard since that his body was picked up and taken to Lemnos Island and buried there....”[15]

Above: William Lund

A significant proportion of the company’s ‘other ranks’ were from Cornwall. The local newspaper in Falmouth reported the local losses.

Above: Lake's Falmouth Packet and Cornwall Advertiser 3 September 1915

Not on the newspaper report, but still a Cornishman living in Falmouth was 47 year old William Hare. Married in 1893 to Florence Annie they had two daughters, Beatrice (who was 20 when her father died) and Rhoda who came along much later, being born in 1912.

Above: William Hare

Helles Memorial

The vast majority of those who lost their lives are commemorated on the Helles Memorial to the Missing at Gallipoli. The walls surrounding this memorial detail (by regiment) the men lost in the campaign. There is listed just short of 850 officers and men who were lost on the Royal Edward.

Above: Helles Memorial (CWGC)

Tower Hill Memorial

The other main place of commemoration of those lost in the sinking is the Tower Hill Memorial in London. This lists the crew on board the Royal Edward who were lost. A total of 127 are named on this Memorial, including the ships Master. Out of a crew list of what would seem to be 220, it would seem that about 58% perished. This - perhaps surprisingly - is better a survival rate than overall (see below).

As well as those crew who were killed, we know from an examination of the Pension Records that the WFA saved, many of the crew who survived suffered injuries varying from amputations and gashes to nervousness and ‘defective eyesight’.

Above: The Pension Record Card for Edward Dyer

Not all of the crew are listed at Tower Hill. Four of the missing are commemorated on the Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth Naval Memorials as they were Royal Naval personnel.[16]

Bodies washed ashore

As mentioned above, one officer (William Bullen Lund) was said to have been buried at Mudros, but there is no evidence of this. Also detailed above were the two graves at Alexandria (the men having died on board the Hospital Ship Soudan). However, research has revealed that three identifiable bodies came ashore; two of these seemingly were washed up on the Greek Island of Scarpentos (now known as Karpathos). These two men are now commemorated at the Syra New British Cemetery. They are Privates Edward George McCrossen, aged 25 of the 2/Hampshires and Albert Benjamin James Thirtle aged 41 of the 1/Essex. They are commemorated with headstones detailing they were originally buried on the Island of Scarpentos but their graves subsequently were lost. [17]

Above: Syra New British Cemetery (cs_cooper: Great War Forum)

The third identifiable grave is that of 2/Lt John Weeks of the Devons, (attached to the 2/Hants). Like McCrossen and Thirtle, his headstone is in Syra New British Cemetery, but is not a ‘memorial for a grave lost’. He is buried in grave II.A.5

Above: John Weeks

The reckoning

With total fatalities of 846 commemorated at Helles, and 132 named at Tower Hill and four named on Royal Naval Memorials in the UK. There are 982 lost with no known grave. In addition, known graves total five (two in Alexandria and three at Syra) which gives a total fatality count of 987. This out of a total ships complement of between 1400 and 1600 (depending on the source) which suggests 65% of those on board were lost. This is a slightly higher percentage than those lost on the Lusitania, which also went beneath the waves in a short time-frame. It is possible that the numbers surviving the Royal Edward were due to the warm waters and the fitness of many of those on board (compared with the cold waters and less physical fitness of those on board Lusitania).

Losses by Regiment

1/Lancashire Fusiliers lost 28 officers and men

2/South Wales Borderers lost 56 officers and men

1/KOSB lost 59 officers and men

1/Border lost 60 officers and men (this is a high proportion of the 74 in the draft).

East Lancashire Field Ambulance lost 61 officers and men.

The 54th (1st/1st East Anglian) Casualty Clearing Station and Field Ambulance lost 69 officers and men

The 18th Labour Company lost 126 officers and men (including two buried in Egypt)

1/Essex lost 177 officers and men (including one buried on the island of Syra)

2/Hampshires lost 213 officers and men (including two buried on the island of Syra)

In addition losses to the crew (including Royal Naval personnel) amounted to 131

Total 982

It is without doubt that the rapid sinking cost the majority of those who were killed their lives. Had the lifeboat drill not just taken place, perhaps most men would have been on deck and not trapped below. It is also without doubt that those who tried to return to their cabins for their lifebelts paid for this decision with their life.

Could the Alnwick Castle have stopped to rescue survivors? Possibly, but to have done so would have put many more men at risk. Should the other vessel referred to in the account of Sgt Alexander Fraser stopped? The decision to sail on was probably sensible if, as the account suggested, the ship was loaded with explosives. In any case, it is highly likely that the vast majority of the deaths occurred immediately the Royal Edward went down, with probably hundreds of men trapped below deck having returned to their cabins immediately after the lifeboat drill.

Article by David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Further reading:

An excellent website created by Kathryn Atkin is dedicated to the sinking of the Royal Edward. See www.royaledward.net

Notes:

[1] It is possible that the publication in 1907 of T. W. Lawson's popular novel Friday, the Thirteenth, contributed to popularizing the superstition. In the novel, an unscrupulous broker takes advantage of the superstition to create a Wall Street panic on a Friday the 13th

[2] The numbers on board the Royal Edward differ depending on the source, but The Times reported the loss on 18 August stating she was carrying 32 military officers, 1350 troops and a crew of 220 – a total of 1602

[3] His true age may have been 64. The CWGC records 26 men between 40 and 49 years but half of the men don’t have their ages recorded, so statistically it would be likely that the figure of 26 ‘older men’ can be more than doubled.

[4] Italy declared war on Germany on 28 August 1916.

[5] Gibson, R. H. & Prendergast,Maurice: The German Submarine War, 1914–1918 pp. 38–39

[6] Pola is now Pula in modern day Croatia

[7] He overstates the numbers on board by a significant margin.

[8] He does not name the ship, but this was the Soudan.

[9] This was almost certainly Ernest Simpson also aged 21

[10] www.gm1914.wordpress.com/2014/04/17/arthur-sanders-and-the-sinking-of-the-royal-edward-an-eyewitness-account/

[11] Hull Daily Mail, Wednesday, 15 September 1915

[12] www.playupliverpool.com/1915/08/31/ex-grimsby-town-player-missing-in-action/

[13] www.paulinedodd.com/from-norfolk-to-gallipoli.html

[14] www.burnleyinthegreatwar.info/royaledwardbook.htm

[15] There is no evidence of Lt Lund being buried at Lemnos. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial at Gallipoli

[16] Stokers John Stewart, Llewellyn Pritchard, Patrick Fitzgerland and Charles Sadler.

[17] The graves record the following:

McCrossen: Buried at the time at Cafealo (on the) island of Scarpentos but whose grave is now lost.

Thirtle: Buried at the time near the Gurgunda Salt Works (on the) island Scarpentos but whose grave is now lost