A Comparative Analysis of the Profiles of the Officers of the 36th (Ulster) Division Between Formation and 1 July 1916

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Comparative Analysis of the Profiles of the Officers of the 36th (Ulster) Division Between Formation and 1 July 1916

Until the beginning of this century it has been very difficult for historians to analyse the profiles of the officer corps in the New Armies formed in late 1914. Consequently, it has been assumed that the newly commissioned officers were similar in background to those of the pre-war Regular Army namely public schoolboy educated members of the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) from landed upper class and professional families.

The National Archives at Kew, London contain thousands of files on the officers who served in the First World War. Examination of these files allows a much more detailed analysis to be made of their respective backgrounds. Moreover, other resources enable the backgrounds of officers whose files are not retained at Kew to be assessed.

This paper analyses and compares these data for the officers of the New Army 36th (Ulster) Division who moved to France with the division in October 1915 and joined the division between then and the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. It demonstrates clearly that, in the context of this division, previously held assumptions about the profiles of New Army officers are mistaken. Comparison is made with earlier published research to demonstrate how the officer profile evolved and changed between the formation of the division in 1914 and 1 July 1916.

Introduction

Holmes notes in reference to commissioned officers in 1914 that “the peerage, gentry, military families, the clergy and the professions provided its bulk with a minority coming from business, commercial and industrial families”.[1] He continues by saying that 67% of the officers were ex-Sandhurst with only 2% commissioned from the ranks. Of the remainder about half (15%) came from universities and public schools mostly via their respective OTCs with the other 15% entering through “the militia back door” ie the Special Reserve or the Yeomanry (Territorials).

Although Holmes was referring to the Regular Army at the outset of the war Bowman notes in a reference from 1994, that historians have long considered erroneously that the officer class in the New Army divisions did not differ that much from the Regular Army in terms of background.[2] The majority of officers were believed to have come from landed, professional and commercial backgrounds with most attending public or grammar schools with OTC detachments.

In order to demonstrate how the officers of the 36th Division compared with this stereotype the profiles of all the known officers of the 36th Division who travelled with the division to France in October 1915 as well as those who joined the division in France between October 1915 and 1 July 1916 were examined. This excludes staff officers, commanding officers and support functions such as Royal Field Artillery, RAMC et al attached to the division.

The vast majority of the information was obtained from the WO339 series of files retained by The National Archives at Kew, London. These vary in detail from very comprehensive to sparse.

Identifying the names of the officers relied on various sources including, inter alia, the Army Lists, the War Diaries, London Gazette and newspaper accounts of the time. However, the Army Lists, published monthly, were notoriously slow in updating the officer names assigned to a particular battalion and were many months out-of-date. Therefore, the list of officers is not presumed to be complete and some may have been overlooked. Nevertheless, 549 officers have been identified who satisfy the above criteria of which 438 (80%) have their files in the WO339 series at Kew available for analysis. Of the remaining 111, other sources as noted below, have provided useful data. Of these 549 officers 82 (15%) did not participate in the actions of 1 July 1916 because they had been previously killed (9), wounded and evacuated (34), had been evacuated ill (28), had been transferred (6) or had been on courses or leave (2). Two were prisoners of war and one had been court-martialled.

Bowman conducted a similar analysis of the 36th Division in which he demonstrates how previously held assumptions about the newly commissioned officer being from the public-school educated upper classes were wrong.[3] However, his focus was on the profile of officers at the division’s formation up to January 1915 and as such provides a valuable baseline for comparison on how the officer profile and composition changed in the eighteen months between then and 1 July 1916. Moreover, he considered a much smaller sample. Officers who were assigned to the 36th Division prior to the move to France but no longer served, for whatever reason, are not considered herein, Bowman having already addressed this cohort within the limitations of his sample.

Officers commissioned at the outset during the final months of 1914 for whom data are available and travelled to France in October 1915, comprised half of those who participated in the 1 July attack allowing for those who did not take part as noted above. The other half were commissioned from January 1915 onwards of which approximately 90 joined after the move to France. 56 of the 100 officers killed or died of wounds on 1 July 1916 (excluding Lt Col Bernard commanding 10/RIR) were commissioned in 1914.

Obtaining a Temporary Commission

Applying for a temporary commission with the 36th Division involved completing the official War Office application form and undergoing a medical. The form required an acceptable reference to the candidate’s moral character from someone of standing who had known him for a number of years, a reference to his standard of education, typically from his former school headmaster or university principal and finally, and most important, the signature of the commanding officer approving his application and who is “well acquainted” with him. If being commissioned from the ranks, this would be his regimental CO. If from the OTC it would be the OTC CO who would formally recommend him for a commission. However, if the candidate was applying directly he had to have the signature of a senior officer to whom he was “well-acquainted”. This could be either sent directly to 36th Division HQ in Belfast or to the War Office in London. If the former, the application would be approved and the 36th Division battalion to which the candidate was to be assigned would be stated. It was then forwarded to the War Office for formal approval.

If the application was sent directly to the War Office, the candidate could state his preference for the regiment to which he wished to be commissioned but this was often disregarded depending on whether that regiment had vacancies or there was more need for his service elsewhere. It was through this process that many officers were assigned to the 36th Division with no connections to the province.

In most cases, Ulstermen or those with close connections to the province, applied for a commission directly to the 36th Division HQ in Belfast. The records examined do not include those who applied and were rejected or commissioned elsewhere nor those who applied directly to other regiments nor those who applied directly to the War Office and were assigned to another division.

This practice was not unusual. Holmes tells of the formation of the Accrington Pals (11th East Lancashire) where in the early weeks of the war, officers were nominated by the mayor with a local mill-owner with no military experience being made commanding officer. Most of the officers were sons of prominent local citizens.[4]

Of the 438 officers for whom data exist at Kew, 196 (45%) were commissioned from the ranks. This is radically different from the 2% typical of the pre-War regular army. Bowman records that 66 of the 231 officers he examined were commissioned from the ranks or 29%. The marked increase over the following eighteen months reflected the greater number of experienced soldiers deemed suitable for a commission along with the losses to the existing officer corps that had to be replaced. A number of the men who enlisted at the outset were almost immediately commissioned with no experience whatsoever. One example is Lt James Douglas from Limavady, Co. Derry. A lowly draper’s assistant with no formal education, he enlisted in 10/RIF in September 1914 and a week later successfully applied for a commission as a second lieutenant. Even in these early days status and education were not a definitive requirement.

Several Scottish regiments actively recruited in Belfast at the outbreak of the war such as the Black Watch. Consequently a number of officers later commissioned from the ranks were Ulstermen serving with 6th Black Watch.

One consequence of the surge in officers being commissioned from the ranks as the war progressed was that many were not from Ulster. Some were serving soldiers in the British Army as well as the Canadian Expeditionary Force and Australian/New Zealand forces and hence had valuable military experience. One example is Englishman Stanley Miller, an experienced NCO with Royal Horseguards who was commissioned into 11/RIF ignoring his preference for a Cavalry regiment.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force provided ten commissioned officers to the 36th four of whom had originally been from Ulster. An eleventh, Lt Ernest Hine, originally from Kent, had been commissioned into 1st East Lancashire from CEF and was transferred to 9/RIR as Adjutant. This excludes those who returned from Canada to enlist and were later commissioned into the 36th.

Examples of non-Ulstermen who were commissioned into the 36th Division are Lt John Findlay, from Kent, a student at Clare College, Cambridge and ex-Glenalmond public school where he had been a member of the OTC. He was commissioned into 13/RIR endorsed by the CO Lt Col Savage with no obvious connections.

On the other hand Dr William Tait Sewell from Co. Durham was commissioned into 11/RIF on the recommendation of the CO, Lt Col Hessey. They knew each other well because they had served together in the University of Durham OTC where Hessey had been Adjutant.

Albert Kemp from a Wolverhampton brewing family was commissioned into 10/RIF on the recommendation of Brig Gen Hickman, the local MP and CO 109th Brigade.

Lt Hugh Foster Chillingworth from Bedford was a medical student at the University of London when he enlisted in the Honourable Artillery Company at the outbreak of the war. After service in France he was commissioned into 10/RIF in May 1915 on the recommendation of the then Adjutant Captain Robert Edward Toker and endorsed by the CO Lt Col Ross Smyth. Toker was also from Bedford and the two families knew each other; Toker’s father was an Army general and Chillingworth’s a surgeon.

Others had family connections with Ulster and applied directly to the 36th Division. The most famous of these was Londoner Lt Geoffrey Cather later awarded a posthumous VC, whose uncle and cousin were serving with 9/RIFu to which he successfully applied for a commission. Similarly, Capt Maxwell Alexander Robertson and his brother 2Lt Frank Leslie Robertson were born in Glasgow and living in England, but because their mother was from a well-known Co. Derry family they successfully applied for commissions in 10/RIF.

2Lt Reginald Lambert Lack from London and his brother-in-law 2Lt Geoffrey Kam Radcliffe from Kendall, Westmoreland were both commissioned into 14/RIR, the Young Citizen Volunteers, and almost exclusively comprising men from Belfast, the former returning from the US to enlist. While Lack’s father did business in Belfast, neither had any obvious Ulster connections.

Alfred Frederick Cook was a London accountant with six years’ experience with the Territorials (1st Surrey Rifles) but enlisted in Belfast into 10/RIF from which he was rapidly commissioned and promoted. Within one year he was Captain and Adjutant.

Welshman Charles George Francis Waring enlisted with 11th Welsh at the outbreak of the war and sought a commission in any Welsh regiment. He was assigned by the War Office to 11/RIF in April 1915 as a 2Lt.

Countless men travelled from overseas to enlist being either émigrés or working overseas. Some with Ulster connections applied direct; others with no such connections were arbitrarily assigned by the War Office. Civil engineer 2Lt Robert Charles Kinniburgh was born in New York and living in Newark, NJ, when he travelled to Lurgan, Armagh to enlist in 16/RIR being commissioned shortly afterwards – his uncle lived in Lurgan. Malcolm Douglas McNeill and his friend Augustus Henry Hall both of whom returned from Ceylon to enlist were commissioned into 12/RIR. McNeill was from Larne, Co. Antrim and Hall from Oxfordshire but both had attended Campbell College together. John Pollit Hampshire was born in Brazil and returned to London at the outbreak of the war. He was selected for training at the Inns of Court OTC training camp in Hertfordshire and then commissioned into the 9/RIF. American Percy Noel Lancaster was working in Trinidad as a civil engineer when war broke out and travelled to London to enlist joining Inns of Court OTC for training. He was commissioned into 10/RIR.

2Lt Gilbert Evelyn Barcroft was an Ulster émigré and naturalized US citizen who returned from Houston, Texas to be commissioned into 9/RIFu. He was from a long established, wealthy Armagh family. Capt Arthur Dawson Allen, originally from Armagh, emigrated to Alberta, Canada and returned to be commissioned into 9/RIFu. Lt Edgar Montague Smyth was born and brought up in Lima, Peru from where he travelled to the UK to be commissioned into 9/RIFu, his family being from Donegal.

The son of the Archdeacon of Raphoe, Capt George Christophilus Garstin, a veteran of the British South African militia, emigrated to Sasketchewan where he worked in ranching. He returned to be commissioned into 9/RIF. Lt Samuel James Hamilton Verner, originally from Tyrone, was working as a clerk in Toronto when he returned to be commissioned into 9/RIF.

Lt Robert Victor Gracey from Donegal, was a banker in Montevideo, Uruguay from where he returned to enlist in 14/RIR.

2Lt Harold Tronson Ozzard was born and raised in British Guiana where his father was a government official. He was a student in Aberdeen in 1914 and enlisted in the 3rd Gordon Highlanders but was discharged “as not being likely to become an efficient soldier”. He re-enlisted in 2/King Edward’s Horse and successfully applied for a commission being assigned to 9/RIFu.

2Lt William Mackenzie Campbell, a chartered accountant also from Cheshire, returned from Buenos Aires, Argentina to be commissioned into 9/RIR. As with Ozzard, there is no obvious Ulster connection.

An estimated 46 men (8%) from overseas were commissioned into the 36th Division either directly or via another regiment through transfer such as Hine and those from the CEF. Rather than be commissioned directly into the 36th, men instead could be commissioned into one of the reserve battalions such as 3/RIR, 17/RIR, 18/RIR, 19/RIR or 20/RIR. From there they would be assigned, once trained, to a 36th battalion in the field.

Analysis

The characteristics of the officers are assessed based on the following criteria where known for each officer :

- Occupation

- Service with the UVF

- Education

- Service with the Officers’ Training Corps (closely related to Education)

- Birthplace, residence and nationality

- Age

Occupation

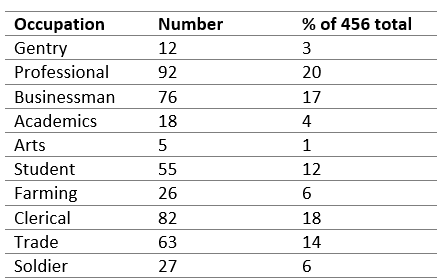

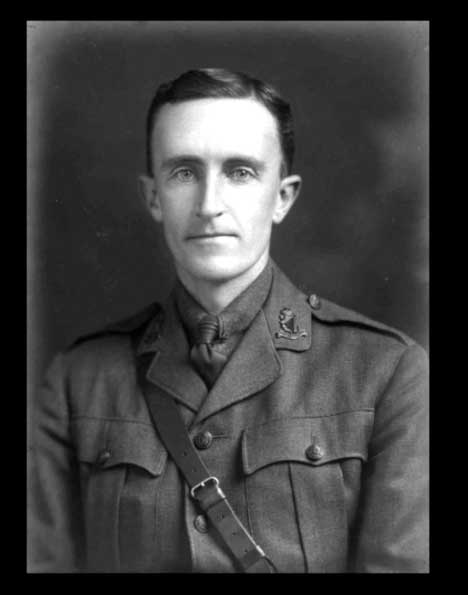

The attestation papers for enlistment in the ranks and the applications for a temporary commission usually give the applicant’s occupation but not always. Moreover, some of the files are missing the applications. Information can also be gained from newspapers and other sources, as noted. Of the 549 officers identified, occupations have been determined for 456 of them (83%) and have been grouped into ten categories, as shown in Table 1.

Professionals are lawyers, bankers, politicians, accountants et al. They are mostly public school educated and come from upper class or wealthy families. Businessman have similar backgrounds many associated with the Ulster linen business which, at that time, was world leading and a major export.

Examples of this “Linen Aristocracy”, wealthy Co. Down families closely associated with the linen business, are the Ewarts (Major William Basil and Capt Cedric Frederick Kelso), Major Adam Primrose Jenkins, the Smyths (Capt William John Haughton and his cousin Capt Edmund Fitzgerald), Capt Charles Henry Murland, Major George Horner Gaffikin, and Capt Arthur Cochran Herdman. Other prominent local businessmen were Major Albert Henry Uprichard, managing director of Forster Green, a major tea and coffee import business established by his late grandfather.

Capt James Samuel Davidson, a director of Davidson & Co. Ltd. owners of the huge Sirocco Engineering Works in Belfast and his friend and fellow director Capt Gerard Walter Matthew, the son of the Bishop of Lahore, India, moved in the same social circles with membership of prestigious sporting associations such as Royal Co. Down Golf Club, Royal North of Ireland Yacht Club and North of Ireland Cricket Club. Most were educated at English public schools (Gaffikin and Matthew attended Uppingham and Clare College, Cambridge and Haileybury and Trinity College, Oxford respectively) and all received immediate commissions at the outset because of their education and social standing.

Bowman quotes Starrett, batman to Lt Col Frank Crozier commanding 9/RIR, observing that most of the officers of the 9th Rifles were Belfast businessmen. None of the officers of the 9th Rifles whose occupation is known were Belfast businessmen on 1 July 1916. Whether this is further evidence of the dramatic changes in the officer corps during the 18 months to July 1916 or an example of Starrett’s typically inaccurate recollections is unclear. Given Bowman’s later comment about Lt Col Omerod, Crozier’s predecessor as CO 9/RIR, and Crozier himself actively seeking officers from outside Ulster favours the latter.

Students were attending university when they enlisted or received a commission and many, but not all, would have come from middle and upper class families. Academics are, by definition, university educated and were mostly school teachers.

Farming were mixed. A number were involved in tea planting in India and Ceylon returning to enlist. Several were ranchers in Canada; others land agents and ordinary farmers.

Soldiers comprise professionals with pre-war service as distinct from enlisted men commissioned from the ranks. It is more surprising how few soldiers were commissioned into the division given that this would have been considered an asset. One example is 2Lt Henry Lee, one of the few Roman Catholic officers, who joined the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons in 1899, served in the Boer War and was awarded a field commission into 11/RIF in March 1916.

Trade and clerical covers the working class occupations who were labourers, apprentices, shipyard workers, mill workers, banking and insurance clerks, shopkeepers et al.

Grouping these together broadly into “Working Class” ie Trade and Clerical, one third of the commissioned officers were so defined with basic education and from families without wealth or influence. Some, such as 2Lt Frank Douglas Gunning, a labourer from Fermanagh enlisted with 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, was wounded at Gallipoli and, upon recovery, was commissioned into 11/RIF, his military experience compensating for his lowly background. A number of the soldiers were from working class backgrounds which is not accounted for here. For example, 2Lt George Henry Webb, formerly a welder from Glasgow, had 18 years’ service with Scottish regiments when he successfully applied for a commission to 11/RIF in December 1914.

Capt William Moore originally from Fermanagh, served for 25 years in the ranks, including six with a Chinese regiment becoming fluent in Mandarin. He successfully applied for a commission in October 1914 into 11/RIF with Lt Col Ricardo CO 9/RIF, acting as reference in his capacity as a JP. No commanding officer formally recommended the applicant and since he was almost immediately promoted to Captain and made battalion adjutant he was obviously known to Ricardo or recommended to him though family connections.

Major Robert Craig Gardiner enlisted in the 5/RIR (Royal South Downs) as a 20 year old bugler in 1884, was awarded the DCM in the Boer War and was commissioned as a Captain in 16/RIR in late 1914. Another Scottish-born enlisted soldier with Royal Scots Fusiliers and Boer War veteran was Lt Alexander Ferguson DCM who was commissioned into 9/RIFu.

Others had military experience in the Boer War, Indian Army and elsewhere but were in other occupations when commissioned. 42 officers had seen active service either receiving field commissions or having served overseas prior to being commissioned eg in the Boer War.

While Bowman had insufficient data to draw definitive conclusions he does note that there were a number of officers commissioned at the outset with working class backgrounds.[5]

Education

On the application form for a commission, the applicant had to provide evidence of having attained a good standard of education. Typically, their school headmaster or university principal would attest to this enabling the school which the candidate attended to be determined. Based on these data, where provided, 106 attended a public school and 129 attended university. Not all public school attendees went up to university and not all the university students had attended public school. However, in that era, there was a close correlation with all such officers consequently coming from wealthy, influential families.

19% of the 549 officers identified were ex-public school and 24% university educated, including the 55 who were students at time of commission. These are not additive, not all public schoolboys going up to university and not all university students coming from public schools. This does not include those educated at Ulster grammar schools including, inter alia, RBAI (Royal Belfast Academical Institution, universally known as “Inst”), Methodist College, Portora Royal, Royal Dungannon, Rainey Endowed and Foyle College. It does include Campbell College, the nearest Ulster had to a public school and since data are incomplete on 111 of these officers these percentages should be considered minima. Or, considering the corollary, over three quarters were not public school or university educated. Bowman records only 47 officers with a university or other tertiary education in late 1914. However, given his much smaller sample, the proportion is comparable being 20%.

Bowman states that “the educational backgrounds of most of the officers in the 36th (Ulster) Division …. remain obscure”. He continues with the contradictory view that “most of the officers in the 36th (Ulster) Division had attended Ulster grammar schools but did not, in some cases, wish to parade this fact, hoping that they would be assumed to be public school products”. This analysis shows that most Ulstermen referenced grammar schools as noted above on their applications and others trade and technical colleges such as 2Lt Matthew John Wright (14/RIR) who attended Belfast Mercantile College. Some attended more basic establishments. One example is 2Lt Gerard Duncan Houston commissioned into 17/RIR and transferred to 10/RIR. He attended Hall St. School, a primary school in Maghera, Co. Derry.

Frank Gunning, noted above, who enlisted in 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers as a “Labourer” appears to have attended Portora Royal, a well-regarded grammar school. On the other hand, 2Lt Robert Taylor Montgomery, a grocer from Portadown serving in 9/RIFu was commissioned into the same battalion in May 1915 with his education attested to by a professor at TCD. There is no evidence that he ever attended the university.

However, this was not always the case as shown by Lt John Pollock, 13/RIR. The education section of his application is signed off by “Clarence Craig, JP Co. Down” something that was not uncommon and typified the somewhat laissez-faire approach to approving candidates by the 36th Division HQ in Belfast in the division’s early days of late 1914.

Officers’ Training Corps

Many public schools and a number of universities had OTC detachments, the former Junior Division and the latter Senior Division. Although the OTC only formally came into existence after the Boer War, universities and public schools had various forms of cadet corps and other quasi-military volunteer units since the 1860s. By 1914 there were 23 universities and tertiary education institutions with OTC senior division contingents. In Ireland, these included the Queen’s University of Belfast, Dublin University (Trinity College), Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and the Royal Veterinary College of Ireland.

There were 146 OTC junior division contingents including Campbell College, Cork Grammar School and St Columba’s College, Dublin, the only three in Ireland. Many were grammar schools although almost all public schools had one by 1914.

119 officers had an OTC background either Junior or Senior division or in some cases both. This represents 22% of the total and compares closely with the numbers with a public school and/or university education. As above, data are incomplete on 111 officers so this is a minimum percentage. Not all students would have been members of their respective institution’s OTC but most would have been. The majority were from Queen’s University, Dublin University (Trinity College) and Campbell College. This is a comparable percentage to the data quoted by Bowman for 1914 albeit based on a much smaller sample. However, Bowman also notes that “there were only two OTC units in Ulster… thus limiting the opportunities”. He neglects that many of the Ulster officers were educated in England at schools and universities with OTC detachments as well as elsewhere in Ireland especially Trinity College. Only about one third of the officers with OTC backgrounds were affiliated to the two Ulster OTC detachments.

In the WO339 file for 40 year old Dublin barrister William Magee Crozier, Brig Gen Hickman DSO commanding 109th Brigade wrote on his application for a commission that he would “distinctly prefer him to a boy from the O.T.C.” despite his age and lack of military experience.[6] Yet by the time of Hickman’s departure from the 36th Division in May 1916, 28 of the officers in the four 109th battalions were former OTC.

Similarly, Bowman notes how Capt John Dunwoodie Martin McCallum’s influence as a former Adjutant of Queen’s University OTC resulted in a high concentration of OTC members in 8/RIR. This study showed that 18 months later only two officers of the 8th Rifles were ex-Queen’s OTC one of which was McCallum.

Whether the increase in OTC officers reflects a change in attitude insofar as OTC membership was considered an advantage later on as opposed to the origins of the division in late 1914 or simply more OTC members were applying for commissions is uncertain. By March 1915, over 20,000 commissioned officers in the British Army were former OTC members.[7]

Queen’s University OTC was used to train freshly commissioned officers from early 1916 They are not included here nor are those similarly trained at the Inns of Court OTC in Hertfordshire.

Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

A unique characteristic of the 36th Division was its supposed links to the pre-war Ulster Volunteer Force, an armed Protestant militia formed to combat the imposition of Home Rule on Ulster. One of the most common myths perpetrated by authors writing about the 36th Division and a popular theme today in Ulster protestant and unionist iconography is that the 36th Division and the UVF were one and the same. Certainly, at the outset in September and October 1914, a large number of UVF members joined the 36th Division. However, this had changed by mid-1916.

Examining the officer files there are three categories with regard to UVF membership. Firstly, those who state on their application for a commission under previous military experience that they were members of the UVF which would have been seen as an advantage. Secondly, those who were definitely not members of the UVF principally because they were resident outside Ulster. Finally, there are the unknowns; those Ulster residents who do not state such membership or their applications are missing from the files.

Of the 549 officers identified, the three categories amount to the following :

- Known UVF Membership : 141 (26%)

- Known non-UVF membership : 242 (44%)

- Unknown UVF membership : 166 (30%)

This is not precise since a number of Englishmen are known to have served with the UVF such as Henry Chevers Maclean, an English barrister. His application for a commission was endorsed by Lt Col Ricardo, CO, 9/RIF noting that Maclean turned up at the 9/RIF enlisting office in Omagh with 32 UVF volunteers, this despite his address being in Birkenhead. Similarly, Major Philip Laurence Kington Blair-Oliphant, from an old Perthshire aristocratic family was closely connected with the UVF in Lisburn. Nonetheless, even if a large proportion of the latter category were UVF members, and this neglects that files exist for only 438 officers, the general conclusion with regard to officers, was that at least half and probably nearer two thirds were non-UVF by mid-summer 1916. This is consistent with the studies conducted by Fitzgerald and Jeffrey.[8] Again, this reflects the division CO Major General Nugent’s influence as well as the increasing number of officers being commissioned from outside Ulster.

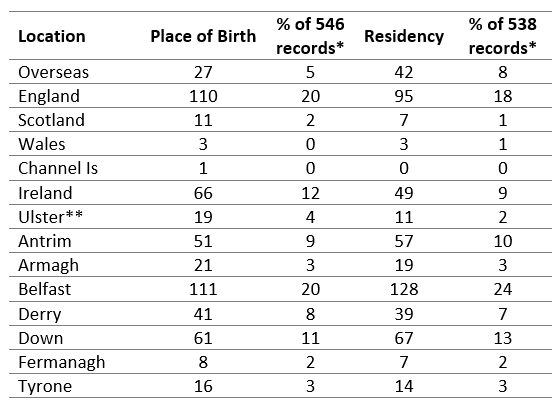

Birth and residency

The place of birth and date of birth of almost all officers has been determined from a variety of sources. These are stated on their applications for a commission and where these data are missing, other sources have been used to obtain the data. Residency at time of commission is more difficult to determine but usually an address is given which provides useful information.

Place of birth can be deceptive as to the officer’s residence and citizenship. For example, a number were born in India to officers serving in the Indian Army but returned to UK. One, 2Lt Maurice Leslie Adamson was born in Burma, the son of Sir Harvey Adamson, the Lieutenant Governor. He was educated at Haileybury where he was a member of their OTC, and emigrated to Canada where he enlisted in the CEF from which he was commissioned into Royal Scots Fusiliers and attached to 10/RIR. He is considered Canadian. Others were born in the US to emigrant parents but returned to Ireland as children. One example is Lt Edmund Arthur Trouton born in West Orange, New Jersey to an American mother and an Irish father. His mother died in child birth and he returned to Ireland as an infant subsequently being educated at Winchester and Trinity, Cambridge. He is considered Irish.

Captain Edward William Collison Griffith was born in Kandy, Ceylon and educated at Bedford School from where he served in South Africa before emigrating to the US and becoming a US citizen. He enlisted in the US 12th Infantry and fought in the Philippine American War. He remained in the Philippines until 1915 when he returned to England and was commissioned into 10/RIR. He has no known Ulster connections and is considered American.

A number of officers born in England and Scotland moved to Ireland for work. Examples are Capt Philip Cruikshank, editor of the Tyrone Constitution, born and raised in Aberdeen. Essex-born Lt Dyker Stanton Priestley, MGC, attended Trinity College Dublin and remained in Dublin as a schoolmaster after graduating. Capt John Griffiths, 12/RIR, born in Chester and educated at University of N. Wales was a schoolmaster at Larne Grammar. Capt Henry Hurst Hooton, 14/RIR, was from Nottingham but moved to Belfast as an apprentice in the shipyards. Gloucester-born Lt Arthur Aston Luce, 12/RIR, attended Trinity College, Dublin where he remained after graduation.

One officer, Lt James Boyd Kennedy Morrow, 13/RIR, was born on a ship, SS Dorunda, in the Red Sea off Aden returning to UK from Queensland, Australia.

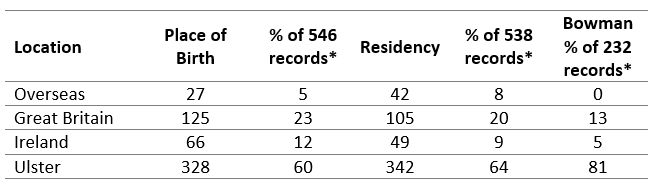

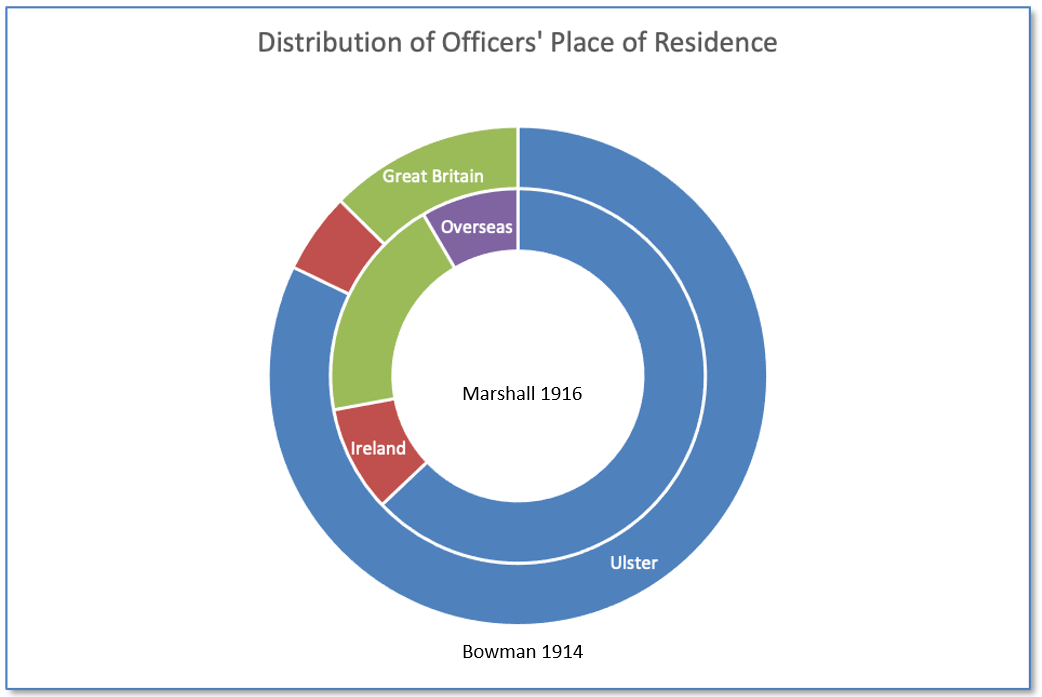

In order to manage the inconsistencies between place of birth and principal residency and citizenship both have been analysed for each officer for whom records exist. These data are included in Tables 2 and 3.

* Rounded to nearest whole number

** Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan. “Ulster” in the group table comprises all nine counties of the province

Whether place of birth is considered or residency, slightly under two thirds of the officers were from Ulster, the majority of these from Belfast. More significantly, almost 40% were not. It is important to recognise that of the 64% of officers resident in Ulster, a number were not Ulstermen but incomers who were working in Ulster. Similarly, of Ulstermen by birth, a number were resident outside Ulster.

Bowman notes that in 1914 all 14 officers of 9/RIFu for which he had records, resided in Co. Armagh. By 1 July 1916, of the 35 records examined and from other information available on a total of 44 officers from the battalion, only 15 or one third resided in Armagh.[9]

Bowman considered 232 officers of which only two were from overseas (Bowman’s Table 4 totals 232 officers while his text refers to 231). 12 were from Ireland, 29 from Great Britain and the remaining 179 from Ulster or 81%. Nevertheless it is evident that the nature of the officer corps between January 1915 and 1 July 1916 changed significantly in terms of their residence with a much greater proportion being from outside Ulster. Again this is to be expected as the influence of the UVF and Carson’s Ulster Unionist Council waned to be replace by Nugent’s more pragmatic approach and the impact of the War Office which encouraged non-Ulster officers.

Age

Of all the factors that determined whether someone obtained a commission, age seems to have been the least important, at least at the outset. The oldest officer in the division on 1 July 1916 was Lt Andrew McQuiston from Ballymena, Co. Antrim, Transport Officer with 15/RIR at 61 years of age. The youngest was 2Lt Cecil Robert Walter McCammond, 14/RIR, from Co. Down at 17 years old born in February 1899. Lt Thomas Graham Shillington from Co. Armagh, 9/RIFu, was four months older.

The relatively low priority given to the applicant’s age is shown by the laxity in requiring proof of age resulting in a number of applicants for commissions lying about their age. Lt Hugh Mulcaster Allom, from a well-known family of London artists, enlisted in 10/RIF in September 1914 giving his age as 39 years. A month later he successfully applied for a commission giving his date of birth as 23 November 1875. His actual date of birth was 23 November 1866. It is unclear why he travelled to Belfast to enlist in the Inniskillings in the first place at his age and with no military experience nor was accepted. Capt. William James Allen, a linen businessman and magistrate from Armagh was commissioned into 16/RIR (Pioneers) in December 1914 giving his birthdate as 15 October 1876, ten years younger than his actual date of birth.

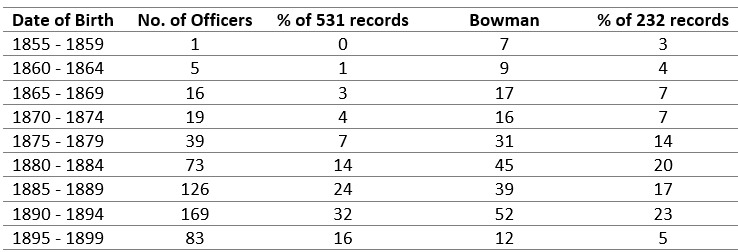

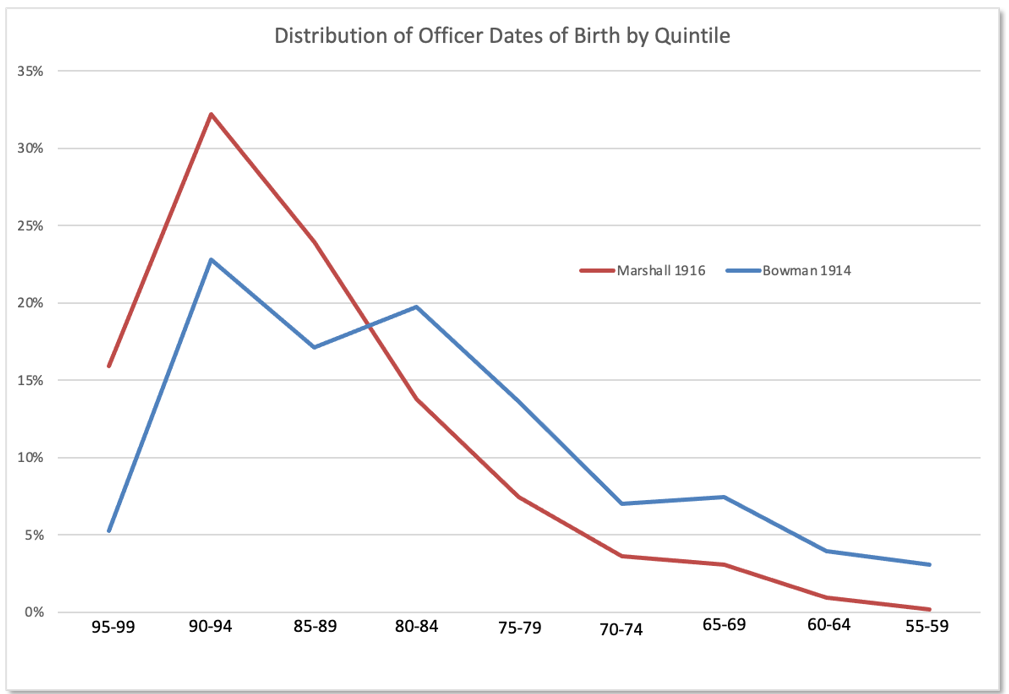

Table 4 summarises the ages of officers by quintile, excluding commanding officers.

Comparing with Bowman’s smaller sample demonstrates how the officer corps changed in the intervening time between late 1914 and mid 1916. The original cohort was much older, on average, reflecting the nature of the recruiting policies at that time as described by Bowman. Nugent’s arrival and the clearing out of the old, unsuited officers bringing in much younger ones is very evident. By 1916, almost three quarters of the officers were no older than thirty as shown in Fig. 3.

Survivability

An enduring myth of the First World war was the supposed brief lifespan of the young subaltern or second lieutenant, the most junior officer. They led from the front and were the first to die. Lewis-Stempel even misleadingly entitled his examination of these junior officers as “Six Weeks - The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War”.[10]

By examining the officer data for the 36th Division this can be shown to be exactly that; a myth. Of the 109 officers killed between arriving in France and the 3 July 1916 including those who later died of wounds, 52 or 47% were subalterns. However, the majority of officers were subalterns so this is statistically more likely. Examining the Army Lists, a typical 36th Division battalion officer contingent comprised approximately 50% second lieutenants.

Of those officers of all ranks who survived 1 July, including those who, for whatever reason did not take part and returned afterwards, 70 were killed before the end of the war representing 16% of the 440 officers in the dataset (549 less the 109 killed or died of wounds up to 3 July). This excludes the many officers who joined the division after 1 July and were later killed. Some were second lieutenants, others had survived long enough to be promoted, some were wounded or ill and evacuated home. Nevertheless, on the basis of the data for the 36th Division, a young subaltern was statistically much more likely to survive than be killed.

Unfortunately, there were exceptions. 2Lt Albert Henry Gibson, 9/RIF and 2Lt Ernest George Boas, 13/RIR both arrived in mid-June on their 19th birthdays and were dead by midday on 1 July. So too was 18 year old 2Lt Richard William Topp, 11/RIF and who had just arrived.

This ignores the many who were wounded or became ill, often severely. Injuries and illnesses that today would be considered relatively minor could be deadly 100 years ago.

Other Ranks

Unlike the Officer files compiled by the War Office and now archived at Kew, most of the files of the enlisted men were destroyed during the London Blitz in 1940. Consequently comparable analysis is impossible given that only very limited data are available. However, data for those men killed and died of wounds or from illness are more extensive enabling basic data comparison to be made.

Examining these data for 1 July 1916 and assuming that the origins of those who were killed are reasonable proxies for all men in each battalion conclusions can be drawn.

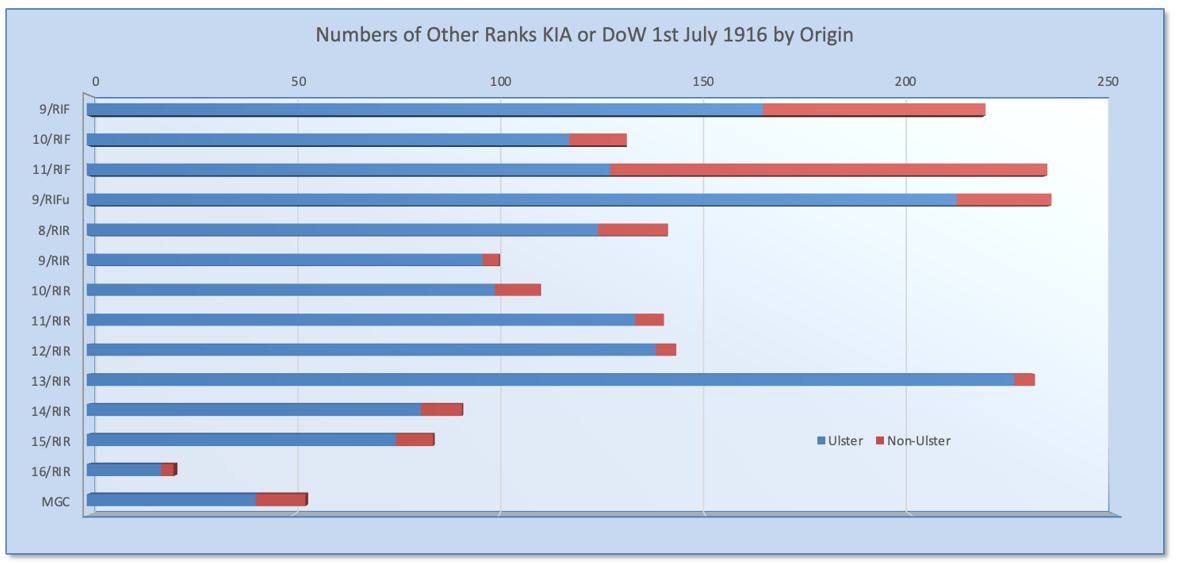

An estimated 1,935 men were killed on 1 July or died of wounds thereafter. Of these 86% were from Ulster, a far higher proportion than the officers. The proportion, however, varies greatly by battalion as shown below.

9/RIF and 11/RIF originating in the rural communities of western Ulster had significant difficulties recruiting locally at the outset and actively recruited in northern England and Scotland. Moreover, the Ulster component is the most diverse in terms of origin across the province. All the other battalions were similar to the “Pals” Battalions of England insofar as they heavily recruited in the local area. 13/RIR is not only almost exclusively comprised of Ulstermen the vast majority are from Co. Down. 9/RIFu are mostly from Co. Armagh and 10/RIF from Co. Derry. The Belfast battalions (8/RIR, 9/RIR, 10/RIR, 14/RIR and 15/RIR) are largely comprised of men from Belfast and Co. Antrim.

Conclusions

This analysis supports Bowman’s conclusions that the officers of the 36th (Ulster) Division were much less associated with the UVF and a public school educated elite than is often believed. Military experience was still a minority asset but becoming more relevant insofar as an increasing proportion of the officers had received field commissions based on their fighting experience in France, Belgium and Gallipoli.

The origin of the officers by 1 July 1916 was much less likely to be Ulster than at the outset examined by Bowman as Nugent actively sought non-Ulster officers and cleared out the “old-guard”. OTC membership was more prevalent than in 1914. The age profile was much younger and the social background more varied with one third being from working class backgrounds.

The War Office played a much more significant role in selecting officers for the 36th Division than in the beginning as noted by Bowman since many officers were commissioned into the division or transferred there with no connection with Ulster.

Bowman notes the excellent performance of the officers in terms of the very few who were court-martialled or otherwise dismissed from the Army. This is further shown by this analysis where only eleven officers from this dataset of 549 were dismissed mostly for inefficiency and unsuitability as an officer rather than criminal actions.

No comparison has been made with other New Army divisions in this study but unquestionably the nature of the officer corps within the 36th Division evolved and changed quite markedly for the better in the 21 months between the division’s inception and 1 July 1916.

Abbreviations

- RIR : Royal Irish Rifles. The number before e.g. 13/RIR is the battalion designation

- RIF : Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

- RIFu : Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria’s)

- MGC : Machine Gun Corps

- RAMC : Royal Army Medical Corps

- CWGC : Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- TCD : University of Dublin (Trinity College)

- OTC : Officers’ Training Corps

Sources of Data

- WO339 Series; The National Archives, Kew

- The Monthly Army List, HMSO; National Library of Scotland

- The London Gazette

- CWGC Database

- Contemporary newspapers especially Belfast Evening Telegraph, Belfast Weekly Telegraph, Belfast News-Letter, Northern Whig and Londonderry Sentinel

- ancestry.com, www.fold3.com along with additional random sources via internet search engines

References

[1] Holmes, R. : “Tommy: The British Soldier on the Western Front 1914-1918”; Harper Collins, 2004

[2] Bowman, T. : “Officering Kitchener’s Armies: A Case Study of the 36th (Ulster) Division”; War in History, Vol 16, 2009

[3] Bowman; Ibid

[4] Holmes; Ibid

[5] Bowman; Ibid

[6] Crozier, W.M.; WO339/403

[7] Haig-Brown, A. R. : “The O.T.C and the Great War”; Country Life Military Histories, 1915

[8] Fitzpatrick, D. : “The Logic of Collective Sacrifice: Ireland and the British Army 1914 – 1918”; The Historical Journal, Vol 38, No. 4, 1995

Jeffrey, K.: “ Ireland and the Great War”; Cambridge University Press, 2011

[9] Bowman, T. : “The Ulster Volunteer Force and the formation of the 36th (Ulster) Division”; Irish Historical Studies, 128, Nov 2001

[10] Lewis-Stempel J. :” Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War”; Orion, 2011

© Copyright 2024. David Walter Marshall.