A Policeman on board : When Lord Kitchener drowned 6 June 1916

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Policeman on board : When Lord Kitchener drowned 6 June 1916

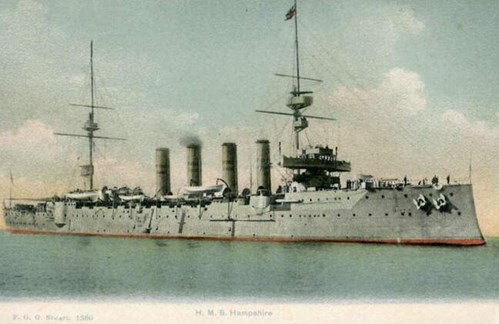

Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, was drowned in HMS Hampshire on 5 June 1916, when it sank just west of the Orkney Islands in Scotland. Kitchener was on his way to a secret meeting with the Russians at Petrograd. This loss was seen as a serious setback to the British war effort. Most people, therefore, failed to notice that amongst the thirteen members of Kitchener's staff who died with him that day was a Detective Sergeant of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, named Matthew McLoughlin.

McLoughlin was born on 6 February 1879 in the parish of Kilcommon near Tipperary to Michael, a farmer, and Bridget McLoughlin. He was the seventh of 14 children and lived in a small house on the side of a hill near the hamlet of Foilnadrough, about a mile to the west of Kilcommon.

He arrived in London in the early part of 1900 and obtained work as a labourer with H P Lee, a building contractor in Fulham; he lived for a short time at 48 Rectory Road, Fulham. He was a single man. He applied for, and was accepted into, the Metropolitan Police on 17 September 1900, as PC 161D Marylebone Police Station. He appears to have served there until 1909, when as a Detective Sergeant, he transferred to the Special Branch, progressing through the ranks to become a First Class Sergeant on 6 March 1915.

During his service with the Special Branch he gained a reputation for being a discreet and extremely capable officer, with a fluent knowledge of the French language and, in the years leading to the Great War, he was involved in many important and sensitive enquiries. One of these cases involved the investigation of a dangerous Indian seditious group which was active in London at that time. The Secretary of State for India was Sir Curzon Wylie and there was great concern for his safety. Sgt McLoughlin in particular had warned the authorities of the threat but was ignored. Soon afterwards an Indian extremist walked up to the Secretary in the Imperial Institute and shot him dead.

Sgt McLoughlin also served as a protection officer to Edward VII and to George V. Prior to his last assignment, he was serving with Lord Kitchener at General Headquarters, St Omer in France. When he boarded HMS Hampshire with Lord Kitchener on that fateful day in early June 1916, it is not known whether or not he was in uniform. Some of Kitchener's staff were senior officers and were in uniform, as was Kitchener himself. Other members of staff were senior civil servants and were wearing civilian clothes.

The Hampshire set sail from the Orkney Islands at about 4.45 pm in the afternoon of 5 June with 655 on board. It originally had an escort of two destroyers but soon lost them due to very poor weather conditions and high seas, which developed into a gale measuring storm force nine.

At about 7.45 pm in the evening a loud explosion was heard and a large hole was reported in the bottom of the ship. Kitchener who had been resting and reading in his cabin, was immediately escorted to the bridge by a naval officer, whose instruction 'Make way for Lord Kitchener' entered the folklore of the war. On the bridge Kitchener was joined by some uniformed members of his staff and was urged to take to the lifeboats by the Commander of the ship, Captain Herbert Savill. It appears he refused.

Eye-witness accounts indicate that there were four uniformed Army officers near Lord Kitchener and he was last seen talking to two of them as the ship was sinking. None of the witnesses saw any of his civilian members of staff, therefore without knowing if Sergeant McLoughlin was in uniform or not, it is impossible at this late stage to ascertain if he was with Kitchener when he died. One suspects that given his reputation as a loyal and devoted protection officer, he would either have been close to him, or at least on his way to him when the ship sank.

There were only twelve survivors. Although many bodies were recovered, including a senior member of the staff, the bodies of Lord Kitchener and Sgt McLoughlin were never seen again. The ship sank in only forty feet of water and remains in its final resting place to this day.

There were several theories at the time as to how she was sunk, ranging from IRA terrorists planting a bomb inside the hull, to torpedoing by submarine. It was eventually established that she was in fact sunk by a mine.

Although the trip to Russia was conducted under the greatest secrecy in Britain, it has been suggested that security may have been breached in Petrograd by German agents there. It is possible that they were aware of the date and route of this small convoy, and that they had time to lay mines in the general location of the ship's most likely route.

Police orders for 7 June 1916 record the death of this brave officer with the usual cold, bureaucratic phraseology: 'Pay to 5th instant.' Sgt McLoughlin left a wife and child who received a lump sum of £53 and 1shilling, plus £10 and 12 shillings per year as a pension.

A memorial to the victims of this tragedy was erected at Marwick Head off Orkney by the local community, with no assistance from the Government.

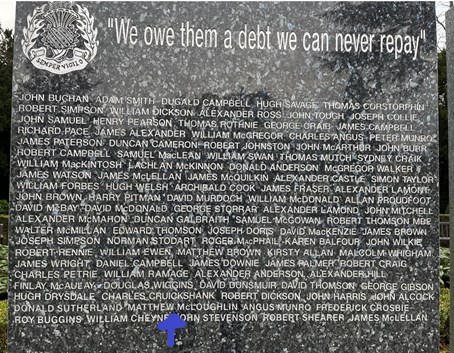

Above: One of the panels at the memorial at Marwick Head

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, whilst having records of all servicemen aboard this ship, do not have one of Sgt McLoughlin, as he was not a member of the armed forces on active service. He remains an unsung hero of the Police Service.

Above and below. Sgt Matthew McLoughlin is named on the Scottish Police Memorial at Police Scotland HQ, Tulliallan Castle in Fife. His name appears on the image below, on the row second from the bottom. (Images courtesy of Stu McAllister, FSA Scot. Trustee and Co-founder Scottish Police Memorial Trust)

Article extracted from the WFA's Journal "Stand To!" No 50 (September 1997), page 16 by R McAdam.

Further reading

Did Kitchener's Decision to Raise the New Armies Wreck Pre-War Plans?