A training exercise goes horribly wrong: The tragedy at Gainsborough, 19 February 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A training exercise goes horribly wrong: The tragedy at Gainsborough, 19 February 1915

At the turn of the last century the Heavy Woollen area of the West Riding of Yorkshire, centred around Dewsbury, was a hive of industrial activity, specialising in the production of heavyweight cloth. One of the main activities in the town was the production of Shoddy and Mungo - this involved the recycling of wool from rags. In 1860, the adjoining town of Batley produced nearly two million pounds of shoddy.

Above: One of the few surviving Warehouses in Dewsbury. Machell Brothers Ltd. Author's collection

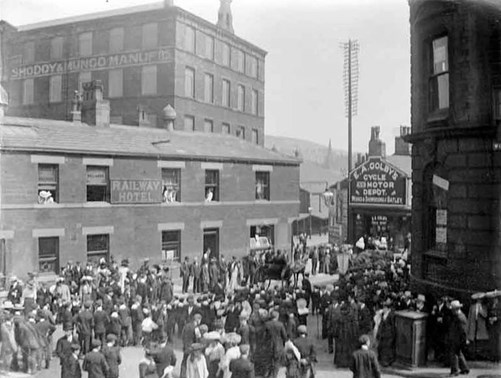

Above: Parade outside Railway Hotel, Bradford Road, Dewsbury, 1910. Machell Brothers Warehouse is in the background. Image copyright and courtesy of Kirklees Image Archive Ref S/C054/1498.

Above: Batley, unknown date. Image courtesy of maggieblanck.com

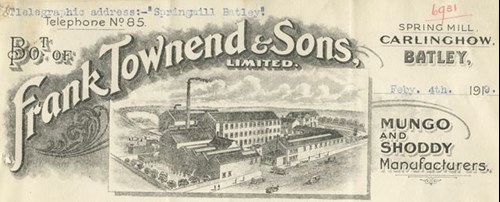

Above: A Billhead of Frank Townend and Sons Ltd from 1919. They were one of the hundreds of firms operating in the woollen industry in the area. Image courtesy of maggieblanck.com

Dewsbury had strong links with the local territorial battalion - the 4th King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Two of the battalion's eight companies were based in the town and had their drill hall in Bath Street.

The 4th KOYLI's catchment area was Wakefield ('A' and 'B' Companies), Normanton ('C'), Ossett ('D'), Dewsbury ('E' and 'F'), Batley ('G') and Morley ('H' Company).

Above: The Drill Hall of 'D' Company, 4th KOYLI at Ossett. Note the stonework above the arch gives a clue to its former use. Part of the building is now a dance studio and the other part is occupied by a gun club. Author's collection

This article relates a disaster that was to affect this battalion before they even set foot outside England.

On Saturday, 2 August 1914, the 4th KOYLI set off, with other local territorial battalions, to their annual camp; it was to be held at Whitby. Many of the men worked long hours, earning poor rates of pay in the local mills, and would therefore have had little opportunity of going to the coast; the annual camp was therefore seen by many as the highlight of the year. The following day, as it became clearer that there was going to be a war with Germany, naval activity could be seen out at sea (the Royal Navy had mobilised already). On Monday, 4 August orders were received for the battalion to return to Wakefield in order to be mobilised.

After returning to Wakefield (which proved more difficult than anticipated due to the rushed arrangements and the fact that the country was in turmoil), the battalion moved to Doncaster. In September the battalion was on the move again, this time to Sandbeck Park, east of Rotherham - the seat of the 10th Earl of Scarborough.[1]

In November the battalion again moved, this time to Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, where it was to undertake coastal defence duties, in case the Germans tried to invade. It was whilst the battalion was stationed at Gainsborough that a tragic accident occurred on Friday, 19 February 1915.

At Morton near Gainsborough there were four gymes or deep pools (described by George Eliot in the book 'The Mill on the Floss'). These pools adjoined the embankment of the River Trent. As part of an exercise to gain experience in bridge building it was decided it would be worthwhile to practice the construction of rafts; 'D' Company, under Captain Hirst, was selected to undertake this exercise.

Above: Harold Hirst courtesy of Yorkshire Indexers. The Original Image from the Medici Co. "Memorials of Rugbeians, who fell in the Great War Vol 1-7". Printed for Rugby School by Philip Lee Warner (O.R.) of the Medici Society Ltd.

Harold Hirst was the 24 year old son of Joseph Hirst, a director of the family firm GH Hirst & Co Ltd. The firm was expanding, and was in the process of building a new factory, which was to be completed in 1916..

Above: Alexandra Mills, Batley. Completed in 1916, this became the new premises of GH Hirst & Co Ltd. Author's collection

Harold, who had been a territorial officer since 1911, took 'D' Company to one of the gymes and started to make a raft (instructions of how this should be done being contained in a manual).[2] Two waterproof tarpaulin sheets were filled with straw and hay, they were each folded over and sealed with rope: these were the two floats for the raft. Planks were then placed on top as a platform. Captain Hirst boarded the raft and instructed a number of men to follow him. According to Captain Hirst's later testimony, the number of men that he allowed on board was between sixteen and twenty. A Lance Corporal who had some sea faring experience was given charge of the punting pole, and at about 12 noon the craft was pushed off from the bank. The raft drifted away from the banking and after about five minutes, being confident that it worked satisfactorily, Captain Hirst ordered that they should be punted back.

Unfortunately, despite being only a little way from the banking (possibly as little as the raft's length away) the punting pole would not touch the bottom - the pole being twelve to fourteen feet long. At this point the raft tilted slightly to one side; despite Captain Hirst shouting to the men to stand still, there was a movement to the other side of the raft. This sudden movement caused the raft to tilt in the other direction, in the words of one of the men "shooting everyone into the water".

Pandemonium broke out; although the men did not have packs on, their boots were heavy and they were out of their depth, a number of non-swimmers panicked and dragged other men under. Some men managed to scramble back onto the raft, others swam to the bank. Captain Hirst, despite being possibly the most heavily burdened man, made it to the shore where he gave orders for someone to go to the nearby village of Morton to summon help. By this time the activity had subsided, and he ordered a roll call to be held. To his horror he discovered that seven men were missing; at this point the battalion's Commanding Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Haslegrave arrived, and ordered Captain Hirst to return to Morton to change. The water was dragged and eventually the bodies of the seven missing men were recovered.

Above: Lt Col Henry John Haslegrave who commanded the 1/4th KOYLI until December 1915. Author's collection.

The inquest into the deaths was heard the following afternoon. Captain Hirst was questioned at length. During the hearing there was some contradictory evidence over the number of men who boarded the raft, it was suggested that it may have been as many as twenty-five. It was explained that the army handbook Captain Hirst was using did not specify the capacity of the raft and it was also suggested that the raft was in fact much further from the shore than Captain Hirst thought. All the men were inexperienced at bridge building, and the coroner reminded the jury that Captain Hirst had been carrying out the instructions of his superior officer. It was the first time he and his men had been engaged in doing such work and had never seen it done before.

The coroner said the gyme was a well-known danger spot and it was a terrible tragedy that they had gone there to carry out the exercise. Whether the men could swim or not, it seemed to him an extraordinary thing that work like this should be attempted in such a dangerous place. He added:

"However, I cannot see the officer in charge of this body of men (Captain Hirst) can in any way whatever be held culpable for what happened. It was his duty to carry out his instructions, and I have no doubt his superior officers were only doing what they had been instructed to do and what had been done by other comrades frequently."

The jury returned a verdict of accidental death on all seven men, adding a rider that it was very regrettable Captain Hirst and his men had been inexperienced and they considered the raft to be inadequate to carry such a large number of men. They also considered the life-saving equipment (one lifebelt) to be inadequate but fully appreciated the duties of the military were dangerous and hazardous, even in training, and recognised the difficulties of those in charge.

Colonel Haselgrave, the commanding officer, told the jury he felt the loss of these young men a great deal more than they could think.

The coroner said the young men may not have died on the battlefield, but they had died the death of soldiers, in the service of their country.

Above: The gyme at Morton, near Gainsborough courtesy of The Unofficial Mamod and Other Model Steam forum

Above: The gyme today courtesy of The Unofficial Mamod and Other Model Steam forum

Above: The area today. Image from Google.

With the exception of Alfred Bruce from Harrogate, all the men who were drowned plus Captain Harold Hirst lived within a four mile radius. The seven men who died were:

- William Atheron (20) son of the late Harry & Elizabeth Atheron of Stanley Road, Wakefield. Buried in Wakefield Cemetery. Regimental number 2434;

- Edmund Battye (22) son of John Battye of Ward's Hill, Batley. Buried in Batley Cemetery. Regimental number 2067;

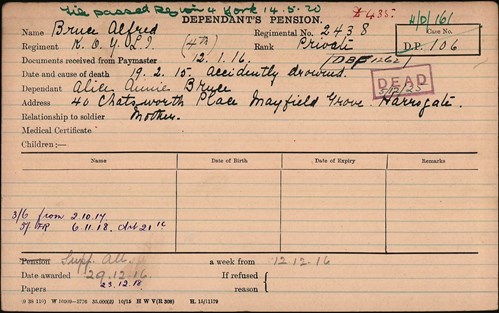

- Alfred Bruce (21) of Chatsworth Place, Harrogate. Buried in Harrogate Cemetery. Regimental number 2438;

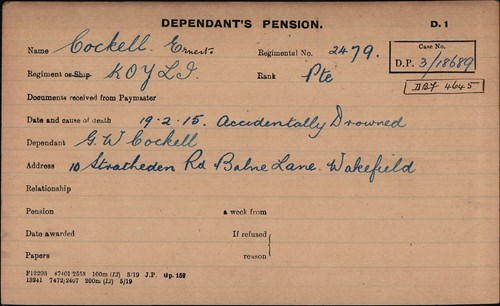

- Ernest Cockell (20) son of Mr & Mrs George Cockell of 10 Stratheden Road, Wakefield. Buried in Wakefield Cemetery. Regimental number 2479;

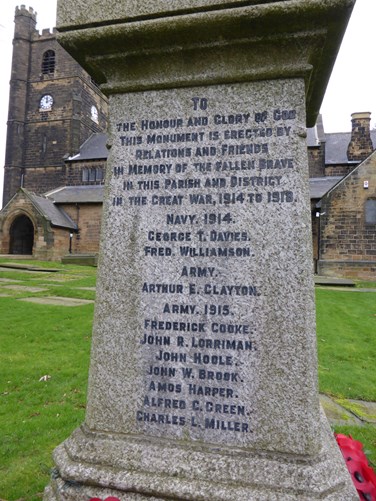

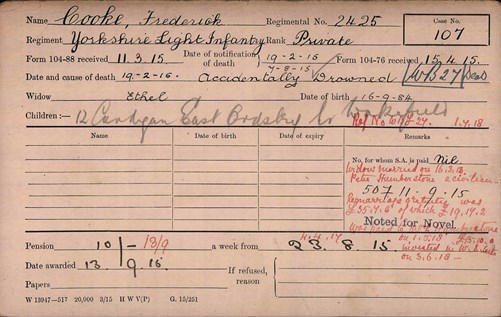

- Frederick Cooke (34) Cardigan Terrace, East Ardsley. Buried at East Ardsley Parish Church. Regimental number 2425;

- William Dent (21) South View, Churwell. Buried in Morley Cemetery. Regimental number 1637;

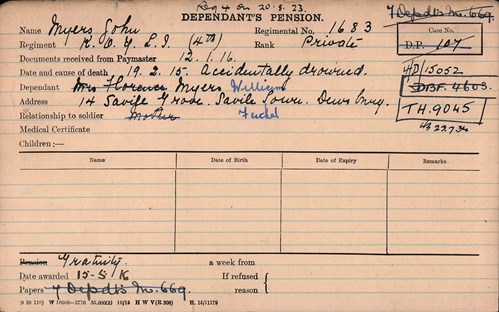

- John Myers, (aged 24) son of William & Florence Myers of 14 Savile Grove, Savile Town, Dewsbury. Buried in Dewsbury Cemetery. Regimental number 1683.

News of the incident made the regional as well as local newspapers, the Yorkshire Evening Post reported the accident the following day:

YORKSHIRE SOLDIERS IN PONTOON ACCIDENT

FORTY MEN CROWDED ON LIGHT RAFT

LEEDS SOLICITOR'S SHARE IN BRAVE RESCUES

No official explanation has been given of the disaster to a pontoon-building party of the 4th Battalion of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (Territorials) at Gainsborough, by which, as was reported in the later editions of "The Yorkshire Evening Post" last night, seven men lost their lives, but from stories of the men engaged in the work it seems as if it were due to the pontoon being badly overcrowded by the forty or more men who were crowded upon it...

...Foremost amongst the rescuers was Lance Corporal Arthur Reginald Chorley,[3] a Leeds solicitor, partner in the well-known firm of Barr, Nelson and Co., of 4 South Parade. Mr Chorley, being anxious, like other Leeds gentlemen, to have a hand in the defence of his country, enlisted as a private in September and was given his stripe at the New Year. He it was who was responsible for saving the lives of Private Creighton, a Batley lad. He plunged into the water, and managed to get Creighton, who was then sinking, to the side.

Sergeant Charles Hemingway, of Dewsbury, one of the youngest sergeants in the battalion, also rendered notable service in the work of rescue, after having the greatest possible difficulty himself to struggle ashore.

The R.A.M.C. men were rapidly upon the scene, and as the bodies were recovered, applied artificial respiration, but in each case the task was hopeless.

Local newspapers reported the funerals in some detail, suggesting that two thousand people attended the funeral of Frederick Cooke in East Ardsley.

Above: Private Frederick Cooke's grave at St Michael's Parish Church, East Ardsley. Author's collection

Above: The War Memorial in East Ardsley church grounds naming Frederick Cooke. Author's Collection.

Despite the accident, the battalion's training continued, and on the 12th April 1915, goodbyes were said as the men were despatched to France as part of the West Riding Division.[4] Within a week the battalion had moved up to the front line and was being introduced to trench warfare in the Bois-Grenier sector.

Above: Grande Flamengrie Farm, Bois-Grenier. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Q48935

Above: Grande Flamengrie Farm, Bois-Grenier. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Q48936

Above: Bois-Grenier sector, August 1915. Part of First Army Panorama 27B. Image courtesy of Peter Barton and the Imperial War Museum, from The Battlefields of the First World War: The Unseen Panoramas of the Western Front (London: Constable, 2005)

The Bois-Grenier sector was a flat, featureless part of the front and prone to flooding. It was a relatively quiet sector and suitable for introducing new troops to the routine of trench warfare.

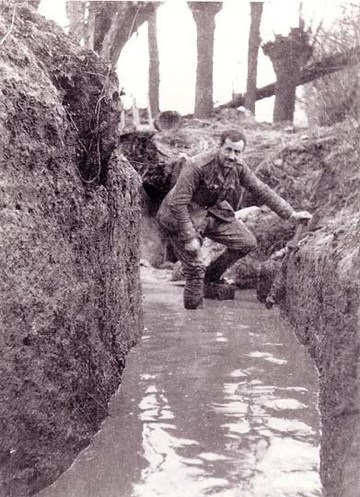

Above: Colonel Philip R Robertson, commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) returning from a tour of his unit's positions in waterlogged trenches at Bois-Grenier in January 1915. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Q51569

(Compare the above photograph to the photograph below: it is clearly taken from the same place).

Above: Cameronian officer Robin Morley negotiates a flooded trench at Bois Grenier in January 1915, after the pumps provided by the Royal Engineers had failed to persuade 'French water to run uphill'. Image courtesy of johndclare.net

Small groups of men were, on successive days, sent to the front line trenches where they learned the do's and don'ts from the more experienced troops. They moved into the front line as an entire battalion on 28th April. Within a few days, the first fatality was suffered when Private John Welsh (aged 19) was killed. He is now buried in Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery.

Above: Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery. Author's collection

After the death of Private Welsh, other casualties followed. The first officers from the battalion to be killed were 2/Lt Roderick Gwynne of Filey (23 May) and Lt Christopher Sugden of Wakefield (25 May). On 24th June the battalion's first middle ranking officer was killed: none other than Captain Harold Hirst who was involved in the rafting accident four months earlier.

It seems that on the day he was killed the battalion was in a newly dug advanced trench adjoining and on the left of the Bridoux Road (Chemin du Vieux Bridoux) and being troubled by German sniper fire.

Above: Chemin du Vieux Bridoux, Bois-Grenier. Image from Google. The cairn (on the right) is to the 2/10th (Scottish) Battalion, Liverpool Regiment.

At 5.30am Captain Hirst, who was said to be a good shot, had picked up an ordinary rifle (as opposed to a periscoped one) and was trying to locate the German sniper when he was shot through the head and killed instantly.

Above: Sniping. 2nd Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Bois-Grenier Sector, March-June 1915 courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Q48960.

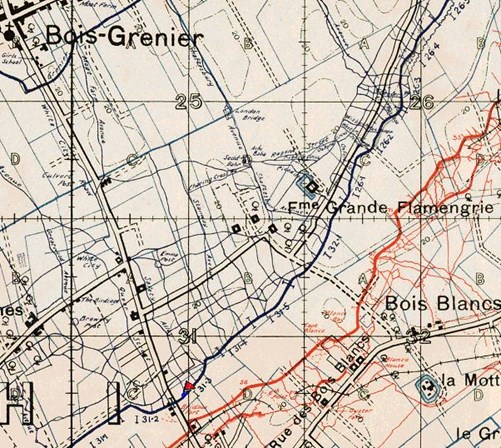

Above: From map 10-36NW4 edition 6 dated 5 December 1915. Courtesy of Great War Digital. The red flag shown in the 'c' square of 31 is the approximate position of the incident as far as the author can ascertain.

Above: The field on the left is the position shown on the above map. Image from Google

An obituary for Captain Hirst appeared in the Dewsbury Reporter two weeks later on Saturday 3 July 1915:

Late last Friday evening the sorrowful news reached Dewsbury that Captain Harold Hirst of the 4th KOYLI had been killed in action.

The telegram, which conveyed Lord Kitchener's sympathy was addressed and delivered at Ravensleigh, Oxford Road, Dewsbury, the residence of Mr & Mrs Joseph Hirst, the parents of the gallant young officer who had passed away. The sincerest sympathy of all will go out to them in their deep distress, and especially to Mrs Harold Hirst, his young widow, and her infant daughter whom Captain Hirst had never seen. It adds deep poignancy to the tragedy that Captain & Mrs Hirst had only been married a year. Normally they would have celebrated the first anniversary of their wedding day on Wednesday last. Almost as soon as their honeymoon was over, war broke out and Captain Hirst was called upon to join his regiment, the First 4th KOYLI, in which he had held a commission for the previous four years. He had since continuously been on military service with his regiment at Sandbeck Park, Gainsborough, and York, and he proceeded to the front ten weeks ago with his regiment.

It is one of the saddest phases of the tragedy that the course of what promised to be a bright and happy wedded life was so early broken by the outbreak of war.

Image: 'Ravensleigh', the home of Harold Hirst's parents. Author's collection.

Captain Harold Hirst is buried in Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery. The cemetery contains nineteen officers and men from the 1/4th KOYLI who were killed in the first weeks of the battalion's service in France and Flanders.

Image: Harold Hirst's headstone at Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery. Author's collection

Image: Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery. Captain Hirst's headstone is the one nearest the camera. Author's collection.

Image: Bois-Grenier Communal Cemetery courtesy of Google.

Further tributes were paid to Harold Hirst:

Harold Hirst was the only son of Joseph Hirst, Woollen Manufacturer of Ravensleigh, Dewsbury, and of Anne his wife. He entered [Rugby] school in 1905, and left in 1909.On leaving Rugby he joined his father's firm, and took a Commission in the Territorial Force. He proved himself to be a most keen and able young Officer, and one who was determined to make his men fit for service abroad when the time arrived. Soon after War broke out his services were rewarded by promotion to a Captaincy, and he was one of the first to volunteer to go to the Front.

He went to France in April, 1915, and, being a good shot, he had killed two or three German snipers, and was in the act of locating others, whose presence was reported as troubling some neighbouring French troops, when he was killed by a shot through the head, in the trenches at Bois-Grenier, on June 24th, 1915. Age 24. Many letters from Officers and men alike bear fitness to his high qualities as a soldier, his fearlessness and high spirits, his charm as a companion, and his staunchness as a friend. He married, 30 June 1914 Gladys Lilian, daughter of Charles Brooke Crawshaw, of Rufford Lodge, Dewsbury, and left a daughter born on April 24th, 1915.[5]

Extract from "Memorials of Rugbeians, who fell in the Great War Vol. 1-7" Printed for Rugby School by Philip Lee Warner (O.R.) of the Medici Society Ltd. Courtesy of Yorkshire Indexers

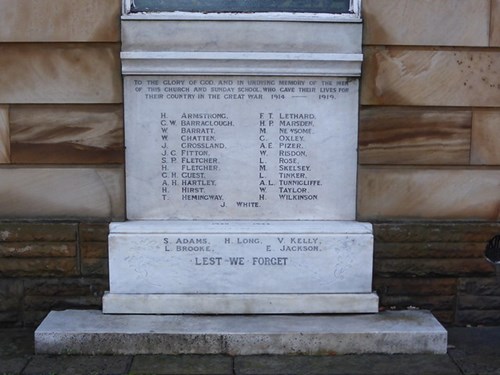

Image: The Memorial outside Dewsbury Central Methodist Church listing Harold Hirst. Author's collection.

Within two days of Captain Hirst's death, the battalion was moved up to Ypres in Belgium. By the end of 1915 the battalion had suffered over 130 fatalities, about a quarter of these being incurred a week before Christmas when the Germans launched a major gas attack on the British trenches.

The battalion served for the rest of the war as part of the 49th (West Riding) Division, incurring over 50 officer fatalities and 760 'other rank' fatalities.

We will never know how many of the men who survived the 43 months of trench warfare remembered the accident at Gainsborough. But the men who drowned in the accident on 19 February 1915 were just as much casualties of the war as those who were killed in France and Belgium.

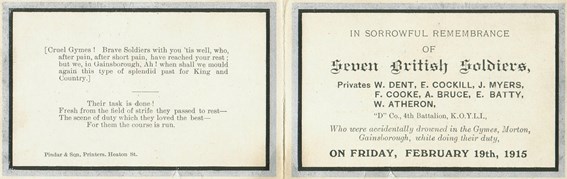

Image: A postcard commemorating the death of the seven men from the KOYLI at Gainsborough courtesy of Andrew Malcolm

Harold's widow, Gladys Lilian Hirst lived until 1972. She died aged 85 in Woking, Surrey. Leila, Harold and Gladys's daughter, was born after Harold was posted to France, and he therefore never set eyes on her.

Notes

[1] The move was apparently to enable the St Leger meeting to take place at Doncaster racecourse. The 10th Earl of Scarborough, Major-General Aldred Lumley, was Commander, Yorkshire Mounted Bde, Territorial Force 1908-1912 and Director General, Territorial and Volunteer Forces 1917-1921.

[2] The eight company system was abolished before the war in favour of a four company system. The (former) 'E' and 'F' Companies had now become the new 'D' Company.

[3] Lance Corporal Chorley was later promoted to sergeant and commissioned in October 1915. He continued to serve in the 1/4th KOYLI, and was promoted to Captain. Arthur Chorley died of wounds in April 1918.

[4] The West Riding Division become the 49th (West Riding) Division on 12 May 1915.

[5] Charles Crawshaw, Harold's father-in-law was a colliery owner and a JP. Rufford Lodge, the home of Harold's wife's parents, was less than 100 yards from 'Ravensleigh', the large mansion where Harold had been brought up. The Bath Street Drill hall of the 4th KOYLI was only half a mile from 'Ravensleigh'.

Article by David Tattersfield with additional material supplied by Peter Bradshaw and Stuart Richmond.

Above: Four of the Pension Record Cards of those who were drowned at the Gyme on February 1915

Further Reading

Malcolm Johnson, Saturday Soldiers (Doncaster: Doncaster Museum Service, 2004) ISBN 0-903524-30-9

Peter Barton and the Imperial War Museum, The Battlefields of the First World War: The Unseen Panoramas of the Western Front (London: Constable, 2005) ISBN 1-84119-745-9