‘A Worthless Scamp’: The Great War of Vincent Riley by John Bourne

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘A Worthless Scamp’: The Great War of Vincent Riley by John Bourne

During the Great War Centenaries, Stoke-on-Trent’s local newspaper, the Sentinel, published many good and interesting features, often in its popular nostalgia section, ‘The Way We Were’. But one recurring story annoyed me. The theme was summed up in a headline on 28 July 2018,‘Great War horrors turned brave soldier into the town drunk’. The ‘town drunk’ was a famous ‘character’ in the Staffordshire Potteries and beyond, Vincent Riley, who was described by the painter and poet Arthur Berry as ‘the King of the Derelicts’. Riley was found dead on 7 March 1951 after being overcome by fumes from a brick kiln on top of which he had been sleeping.

Sneyd Pipe Works, near the loop line railway bridge, off Hot Lane, in Burslem. This is where Riley died in 1951. Image courtesy www.stokesentinel.co.uk

My father was a foreman at the brickworks concerned. I was a month short of my second birthday when Riley died, but his legend outlived him and he was a real presence in my childhood. In that sense, I ‘remember’ him. (My friend and fellow Potteries’ man, Mike Taylor, was astonished to learn recently that Riley died two years before he was born. So aware was he of the name as he was growing up he thought their lives must have overlapped.)Central to the Riley legend is that he was a ‘war hero’, who had been awarded the Military Medal, and who had turned to drink because of his experiences during the war. This story has been repeated so often that it has become canonical. A lot of people in the Potteries clearly want to believe it. It is time to put the record straight.

The Legend of Vincent Riley’s War

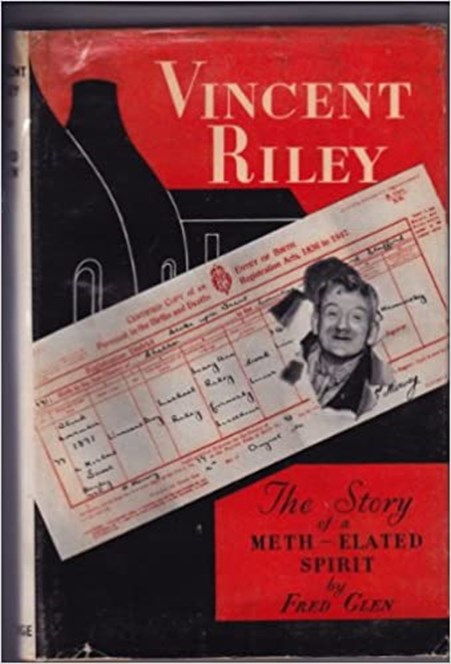

Levison Wood, historian of the 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, recently drew my attention to an article in the Sentinel published on 24 October 2016. Riley was the subject of a biography, Vincent Riley: The Story of a Meth-Elated Spirit, by Fred Glen, published in 1951, shortly after Riley’s death. Most accounts of Riley’s war take their inspiration and their ‘facts’ from Glen’s opaque and date-free account of Riley’s service. Glen tells us that Riley enlisted in the 5th North Staffordshire Regiment (later the 1/5th)almost immediately after the declaration of war, having been disappointed in his attempt to re-join the Royal Navy. (Riley’s naval ‘career’ will be dealt with later.)

Above: Cap badge, North Staffordshire Regiment (NAM. 1964-04-86-51)

We are told that Riley joined the 5th at Tidworth Camp on Salisbury Plain. Glen then goes on, somewhat disingenuously, ‘It would be difficult to say with any certainty the date[Riley] first went into action, but it appears that some time after the 5th North Staffordshire Regiment fought their valiant battle at Loos, in which they lost their heroic commander Colonel Knight, he was wounded whilst on the Menin Road. After a brief convalescence at Poperinghe he returned to the line, and was on night patrol when shrapnel from one of Jerry’s five-point-nine shells shattered his left arm and permanently paralysed his fingers. This time the wounds being more serious, he was dispatched to the Canadian General Hospital at Rouen, and later transferred to Calais.’ The Sentinel article takes this threadbare narrative and embellishes it by placing Riley in the actual history of the 5th North Staffords, so we hear nothing of Tidworth (sensible, as the 5th were never there) but learn that Riley forged a bond with his fellow soldiers at ‘Luton and Bishop’s Stortford’, before deploying to France on 4 March 1915, where he ‘would have faced the “liquid fire” attack at Hooge’ [30-31 July 1915], before ‘climbing out of the trenches alongside his brothers in arms to attack the Hohenzollern Redoubt’ [13 October 1915]. We know very little for certain about Riley’s time in the army. His service file fell victim to the Luftwaffe in September 1940, as so many did. But there is enough evidence - and lack of evidence - to show that the story related in the Sentinel is pure fiction. It is possible to state categorically that Vincent Riley did not join the army in 1914 and he did not serve abroad in 1915.

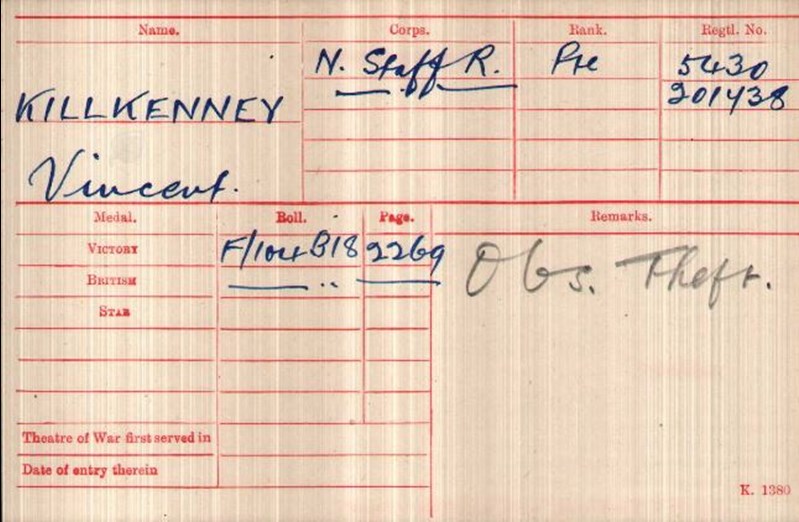

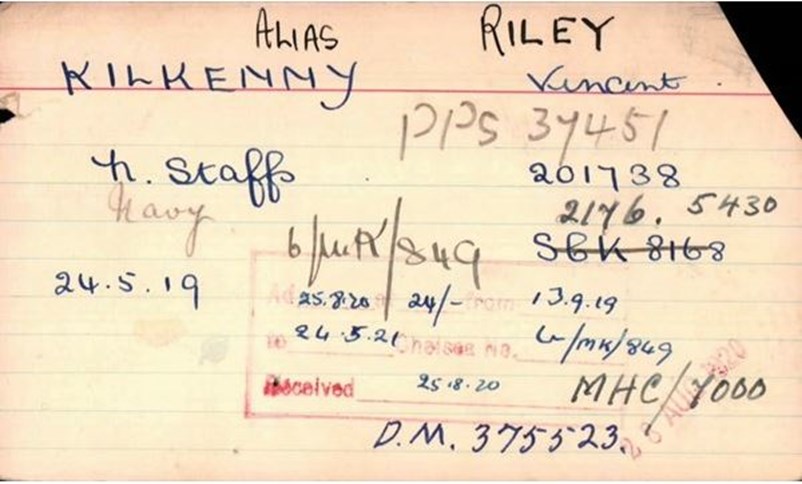

Riley’s Medal Index Card [MIC] shows that he joined the North Staffordshire Regiment under the name ‘Killkenney’, something not mentioned by his biographer. (I owe this discovery to Andy Johnson, of the Wolverhampton WFA.)

When was this? We know that on 6 July 1915 Riley had been sentenced to a month’s imprisonment by Burslem Police Court for ‘attempting to steal’ and so was not only in England but also in gaol at the time of the Hooge ‘liquid fire attack’. The MIC shows his original service number as 5430. The block of numbers containing ‘5430’ was not issued until the end of August 1915. Information recently discovered by Su Handford of the West Midlands Police Military History Society in the Police Gazette absentee and deserter records shows that Vincent Kilkenny [sic] enlisted on 3 September 1915 in the 3/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. This was a third-line Territorial unit that did not form until May/June 1915.Did this date of enlistment leave enough time for him to move to the 1/5th Battalion and take part in the Hohenzollern attack? The answer is ‘no’. The 3/5th North Staffords was a Home Service unit. Its members were not liable to overseas service in 1915 unless they had signed the Imperial Service obligation and even if Vincent had been prepared to serve abroad he would had to have undergone a period of training at home, probably six months, before being drafted. I looked at the service numbers of 221 men of the 1/5th who were killed at the Hohenzollern Redoubt on 13 October 1915. None had a service number beginning with ‘5’. There is also the inconvenient fact that on 3 November 1915, twenty-one days after he was supposedly taking part in the ‘deadly charge’ at the Hohenzollern, Riley was arrested in the Potteries, along with his mother, Mary Ann, for stealing clothes from the house of Mary Ann’s daughter – and Vincent’s sister – Bridget. During the trial, which took place on 12 November 1915, he admitted in court that the purpose of the theft was to obtain civilian clothes to allow him to desert from the army. Mary Ann was sentenced to a month in prison, Vincent to a month with hard labour and it was ordered that on his release he should be returned to his unit, the 3/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment [my emphasis]. He was still in this battalion on 16 March 1916 when he was sentenced to a further two months in prison, with hard labour, on a charge of criminal damage. It is clear from the evidence at this trial that he already had a serious drink problem. Inspector Middleton described him as a ‘worthless scamp who had received several terms of imprisonment for theft’ and been absent from his battalion for five weeks. If you are still in any doubt, Riley/Killkenney’s name does not appear on the North Staffordshire Regiment’s Medal Roll for the 1914-15 Star, which it would have done had he been in France with the battalion in 1915.

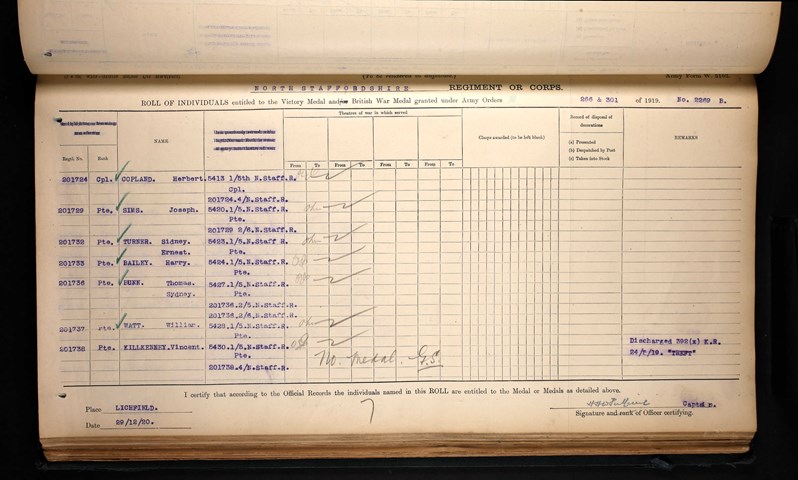

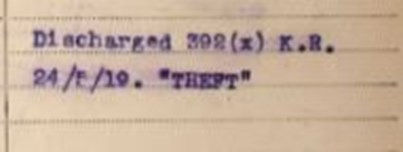

The North Staffordshire Regiment’s Medal Roll does show that Vincent Killkenney was entitled to the British War Medal and Victory Medal, though he was denied both for ‘theft’.

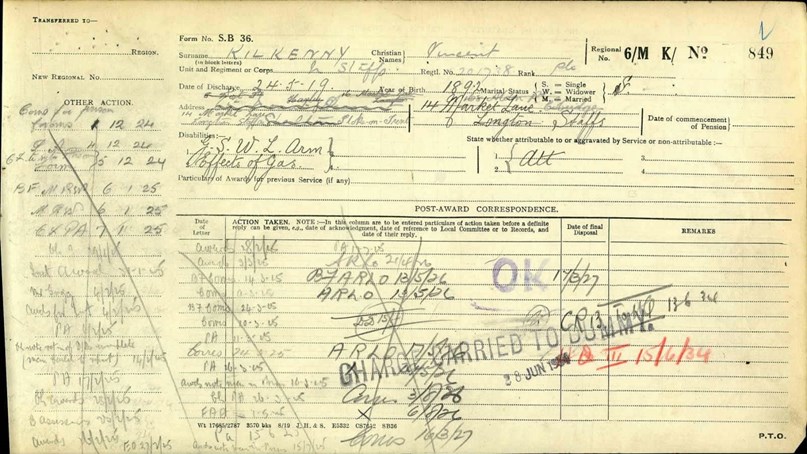

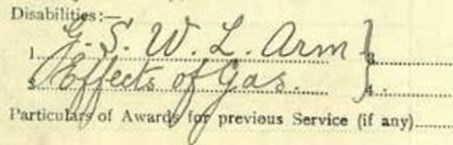

This means that he must have served abroad in a Theatre of War, something confirmed by his Pension Ledger, which lists his wounds as ‘GSW [gunshot wound] left arm’ and ‘effects of gas’.

But pinning down exactly when he was abroad is difficult, if not impossible. 1915 has already been ruled out. The evidence of his criminal record confirms that he was in England at least until some point in May 1916. During another court appearance in July 1918, Detective-Sergeant Longmore said that Riley had served in France from ‘May to December 1916’, though he also said that Riley had volunteered in August 1914, which is incorrect. The Sentinel appears to be ‘Vincent-free’ after his conviction in March 1916, which may indicate that he was out of the country. He was rarely out of the local papers and of the courts when he was at home. The passing into law of the Military Service Act in January 1916 introduced conscription for single men aged 18-41. It came into force on 2 March 1916. This put an end to ‘Home Service’ units. Soldiers in the 3/5th North Staffords were now available for drafting. The soldier with the service number immediately before ‘Killkenney’s’, 5429 Private C.W. Chorlton, had also enlisted in the 3/5th on 3 September 1915. He transferred (or was transferred) to the 1/5th on 4 April 1916, joined “C” Coy on 23 April 1916 and was killed at Gommecourt on 1 July 1916. There were 43 men of the 1/5th killed that day, seven of whom had a number beginning ‘54’. The highest number is 5499. As Dr Bill Mitchinson points out, ‘although men were not always drafted according to their numbers/dates of enlistment, this does suggest that a reasonably sized draft of men who enlisted at about the same time as Chorlton and Riley was despatched to France’. Riley might have been one of them, at least after his release from prison in mid-May. There may be further support for service abroad in 1916 in Glen’s claim that Riley was awarded the Military Medal for bravery ‘at Ransart’. (I will come back to the Military Medal later.) This is an obscure place. It suggests that only someone who had actually been there would have heard of it. The 1/5th spent a lot of time in and around Ransart in July 1916 after their disastrous attack at Gommecourt. They never really went away from the area for the rest of 1916. They moved in and out of the line and for a lot of the time were in the trenches near Monchy-au-Bois. There were a number of trench raids in the area of Ransart on 8-9 September, 20 September, 3 October and 26 October. The 1/5th also made an attack on 13-14 March 1917 at Rossignol Wood, about four miles from Ransart, for which several Military Medals were awarded, though none to Riley/Killkenney.

Service abroad in 1916 must remain a possibility, though there are problems with it. If Sergeant Longmore’s statement about ‘May to December 1916’ is correct, what was the reason for Riley’s return home? The pensionable wound he sustained was a serious one. Had he sustained it in 1916 he would surely have been discharged as ‘no longer fit for military service’ and granted a Silver War Badge.

Had he returned home on leave and deserted, he would surely have been rounded up and sent back. Riley was definitely in England for most of 1917. He was implicated in a house breaking at the Down Banks, Stone, on 25 May and a warrant was issued for his arrest. The other perpetrator was described as a ‘young, married woman’ called Winifred Lockett. Riley was tried and found guilty at Stafford Sessions (Stone) on 16 October 1917 of ‘receiving’ the goods stolen on 25 May. He was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, which were spent in Shrewsbury Gaol. He was released on 1 January 1918. His intended address on ‘liberation’ was 168 Elder Road, Cobridge, his sister Bridget’s house. His occupation is stated as ‘collier’. We lose track of Riley between 1 January 1918 and July 1918, when he reappears again in court in the Potteries, charged with stealing a silver watch. The headline at his first court appearance on 5 July 1918 reads ‘Wounded Soldier in Trouble’. When he was sentenced, the report’s headline was ‘Light sentence for wounded soldier’. He got one month, again spent in Shrewsbury Gaol. He was released on 9 August 1918. This time his intended address on liberation was ‘Army, Ripon’, occupation ‘soldier’. July 1918 was the first time that Riley was described in court as being wounded. Detective-Sergeant Longmore specifically stated in his evidence that Riley was not entitled to be wearing a medal ribbon (presumably that of the M.M.). Riley replied that he had only received the medal just before returning from France, where he had been ‘engaged in the Secret Service’. This implies that his ‘return from France’ was earlier in 1918.

If there is a kernel of fact in Glen’s account of Riley being wounded while serving with the 5th North Staffords ‘on the Menin Road’ and convalescing ‘at Poperinghe’, before being more seriously wounded and evacuated to a Canadian hospital at Rouen and then to Calais, this could only have occurred in April 1918.The 1/5th North Staffords ceased to exist on 30 January 1918, during a major reconstitution of the BEF. Part of the battalion amalgamated with the 2/5th in 176 Brigade, 59th Division, the newly-amalgamated battalion being designated the 5th North Staffords. 59th Division suffered badly in the German offensive launched on the Somme on 21 March. On 1 April it entrained for the Ypres Salient, being concentrated in the vicinity of Poperinghe. It absorbed a draft of reinforcements on 5 April and moved up to the Lys sector on 13 April, where the Germans had launched another major attack. The battalion took part in the Battle of Bailleul (14-15 April) and the First Battle of Kemmel Ridge (17-18 April). It was withdrawn with the rest of the division on 26 April and charged with digging a new defensive position near Poperinghe. No. 7 Canadian Stationary [not General] Hospital was established at Rouen on 24 May 1918. Rouen is some distance from the Salient. There were hospitals much closer, though Rouen was the base for the Territorial Force in France. If Riley was hospitalized in Rouen he could have been evacuated from there. Moving him to Calais makes little sense. There is, however, a further possibility. The Sentinel reports of Riley’s court appearances in April 1919 describe him as being in the 4th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, which was in the Ypres area, including Poperinghe, as part of 105 Brigade, 35th Division, from January 1918 until mid-March when it moved south to the Somme. If he had been wounded in April 1918 with the 5th North Staffords why would he be with 4th, in April 1919, unless he was wounded while with that unit. We may never know. Riley/Killkenney, along with all other TF soldiers, was issued with a new six digit number, in his case 201738, early in 1917. It meant that from then on Riley/Killkenney would retain this service number even if he was transferred to a non-TF unit, such as the 4th North Staffords. 4th North Staffords were still in France, though demobilizing, in April 1919, and so not acting as a ‘holding unit’ for wounded soldiers in England.

The signing of the Armistice did not bring Vincent Riley’s army career to an end. His last appearance in the pages of the Sentinel as a soldier was in April 1919, in an account headlined ‘SOLDIER’S MEAN THEFT’: ‘Vincent Riley, a soldier in hospital uniform was charged with stealing a handbag containing various articles of the value of £5 2s., the property of Mrs Rosa Clarke of 14 Albert Terrace, Hanley, on 28 March. It was stated that he went to the house and asked if he could have a wash and brush-up as he did not want to return to Stoke War Hospital in dirty condition.’ While Mrs Clarke was making him some tea, he effected the robbery. This was the same scam he had used in July 1918. He was sentenced to six months in prison on 12 April 1919, the Chairman of the court describing his actions as a ‘mean and despicable action to trade on the sympathy of an old lady’. This meant that he was in prison when he was discharged from the army on 24 May 1919. It also illuminates the statement on his Pension Card that his pension, to which he was ‘admitted’ on 13 September 1919, should not be paid while he was in prison.

Vincent Riley died, rather unexpectedly, despite his lifestyle, a month after Fred Glen handed his typescript over to the printer’s.

Glen added an epilogue, entitled ‘FINIS’, the last sentence of which reads ‘Sleep well, Vincent Riley, M.M.!’ I was not clear until I read the Glen book recently whether people presumed that Riley had been awarded the M.M. and he failed to disabuse them of the fact or that he claimed to have been awarded it. It was certainly the latter. Medal awards are not kept secret. They are intended to inspire as well as to reward. Communities and institutions are keen to be associated with medal winners. If Vincent Riley/Killkenney was awarded the Military Medal you would expect to find evidence of it. There is no such evidence. A medal award to him does not appear in contemporary battalion War Diaries, where plenty of other such awards are noticed, or in the post-war battalion history of the 5th North Staffords. No medal is listed in Jeffrey Elson’s Honours and Awards – The Prince of Wales’s North Staffordshire Regiment, 1914-1919(2003) or in The Complete Military Medal Roll 1914-19 (3v. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2019) or in the official London Gazetteor on his Medal Index Card or in the North Staffordshire Regiment Medal Rolls or in the pages of the local press. The absence of evidence in this case is compelling evidence of absence. Vincent Riley/Killkenney was not awarded the Military Medal.

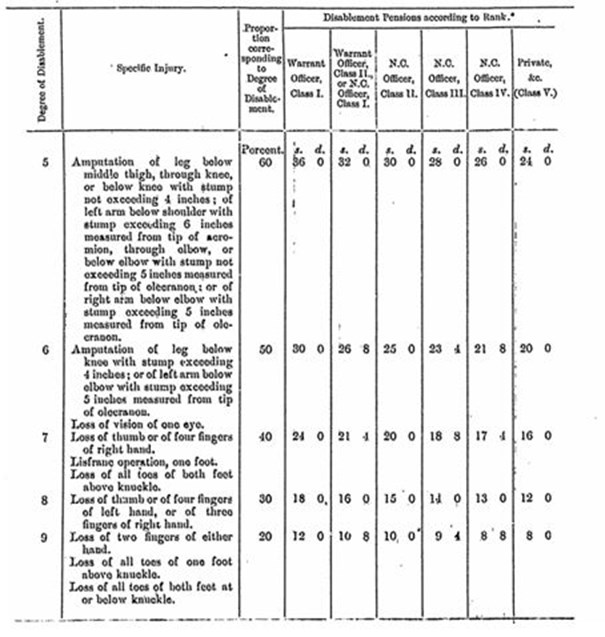

He was, however, awarded a pension of 24s (£1 4s) a week, with effect from 13 September 1919. I am grateful to Craig Suddick for the following explanation: ‘The pension was paid at an initial rate based on the table below (1919 table). If the level of disability wasn't shown they'd pick an equivalent level and start with that. A board would re-assess it relatively regularly until it was determined to be stable and then a final award could be paid.’

The initial award of 24s a week for a private soldier undoubtedly reflects a serious level of disablement (60 per cent). Had Riley received the wound early in the war, he would surely have been discharged. This is further suggestive that the wounding came much later, probably in 1918. Riley’s wound was reassessed periodically. His pension was reduced to 20s (50 per cent disablement) on 4 March 1921 and to 16s (40 per cent disablement) on 12 April 1922. The report of a court appearance at Nantwich on 24 March 1936 stated that his pension had been reduced to 12s a week (30 per cent disablement). It is not possible to conclude from the surviving documentation (where he is shown as ‘Kilkenny’) if or when his pension ceased.

There may be people reading this who conclude that Riley’s pensionable wound entitles him to be regarded as a ‘war hero’. Indeed, there may be people reading this who believe that every soldier who experienced ‘trench warfare’ was a hero. As my old tutor used to say, ‘this is a point of view’. I used to espouse it myself. ‘I suppose you were all heroes,’ I once remarked to a veteran of the trenches, only to receive the withering rebuke ‘heroes, my arse’.

Who Was Vincent Riley?

Vincent Riley was born at 16 Herbert Street, Hanley, on 3 November 1891. He was the fifth child and second son of Michael Riley, aged 40, described as a ‘general labourer’, and his wife Mary Ann (nee Matthews), aged 32. His parents married on 25 July 1875 at the Roman Catholic Chapel in Cobridge (now St Peters’ R.C. Church). Some people have made much of Mary Ann’s ‘Irishness’, but she was born in Stoke (in 1856), her father was born in Trentham, Staffordshire, and her mother in Acton, Cheshire. Michael Riley was Irish born. He was described as a ‘collier’ in 1875, so ‘general labourer’ looks like a bit of a come down, though he is again described as a miner on his death certificate. Glen attributes Vincent’s problems to the death of Michael Riley, whom he characterises as a hard-working man who provided for his family. Mary Ann then emerges as an heroic, single mother, struggling against poverty to bring up a ‘large family’. This is dubious. By the time Michael Riley died on 23 January 1897, Catherine was 18, Bridget 16, James 13 and Etheldreda 11. Catherine married the same year her father died. Bridget married in 1901.James seems to have left the area and moved to Lancashire. By 1901, aged 18, he was living with a cousin at Haydock and by 1911 was married and working as an engineman in a coal mine at Burtonwood, near Warrington. Etheldreda married in 1902. Mary Ann appears to have been living with John Kilkenny, who had been a witness at her marriage, for some time before Riley’s death. She gave birth to a daughter, Winifred, on 23 December 1895. She registered the birth as ‘Mary Ann Kilkenny, formerly Matthews’ with the father as ‘John Kilkenny’. Winifred was born at Kilkenny’s address, 1 Fogg Street, Newcastle-under-Lyme. Despite Kilkenny’s name appearing on the birth certificate, Mary Ann was assaulted by him in High Street, Burslem, in March 1896 when she tried to get him to sign a document admitting paternity of Winifred. The assault on her was reported under her maiden name, Matthews. Despite this, Mary Ann married Kilkenny on 30 August 1897, something Glen fails to mention. As we shall discover, Kilkenny was not an upgrade on her first husband. Vincent seems to have fallen down the cracks between Mary Ann’s two relationships, ‘nobody’s child’, left to live on his wits and on the streets.

We next see Vincent in the 1901 Census living with his mother, step-father, half-sister Winifred and half-brother John, at 42 Bexley Street, Hanley.

A view along Sydney Street in Hanley c1968. At the end is Bexley Street. Courtesy of www.potteries.staffspasttrack.org.uk

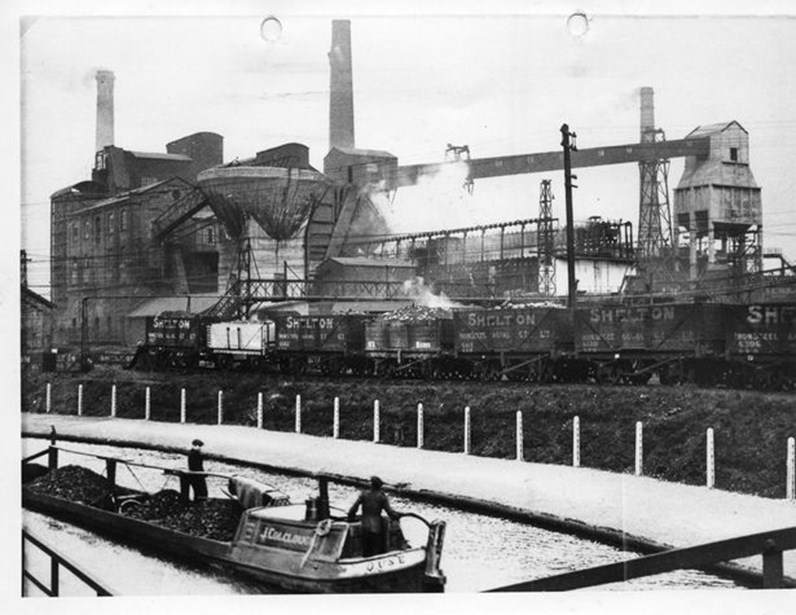

Kilkenny is shown as a ‘steel works labourer’. In evidence at a trial in 1904 the Deputy Chief Constable of Stoke, William Williams, said he did not consider that Kilkenny was a ‘hard working man’. He had received monetary compensation for the loss of any eye at the Shelton Iron & Steel Co. but had squandered the money on drink. Kilkenny had been charged with being drunk in charge of a child - his son John - in 1903, while Mary Ann was charged with being drunk and disorderly later the same year. They were both prosecuted by the NSPCC in August 1910, charged with neglecting John ‘in a manner likely to cause unnecessary suffering and injury to health’. The prosecuting solicitor described Kilkenny as ‘practically a tramp’ and Mary Ann as a ‘hawker’. Both were ‘addicted to drink’. Kilkenny was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and Mary Ann to two months’. John was taken into the care of the Union workhouse and any attempts on the part of his parents to remove him were to be strongly resisted. At the time of the 1911 Census no children were living with them. Kilkenny died in 1919, Mary Ann in 1925.

Vincent makes the first of very many appearances in the pages of the local press on 13 October 1903 when he was charged along with another boy with stealing a currant loaf from a shop in Hanley. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to four strokes of the birch. Advocates and defenders of corporal punishment argue that the birch was an effective deterrent and anyone who was subjected to it was unlikely to err again. This was not the case with Vincent Riley. On 21 May 1904 he and two other boys were found guilty of a scam to rob a chocolate vending machine on Milton station. They had obtained metal disks from the forge at Etruria to use as pennies. This time he was sentenced to twelve strokes of the birch. On 20 August 1904 he was again arrested for stealing chocolate and was fined 5s 6d and costs. He was back in court again on 15 September 1904, charged with being on the premises of the Shelton steel works for the purpose of stealing coal.

Shelton Steel Works - https://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/news/history/shelton-bar-steel-works-potteries-3179667

He was not yet 13 years old. In evidence to the court, Vincent claimed that his mother had thrown him out and told him he was old enough to earn his own living. Mary Ann denied this, stating that Vincent had left home to live with his sister [probably Bridget or possibly Etheldreda] because she allowed him to stay out all night, while Mary Ann insisted he be home by nine o’clock. The daughter’s evidence contradicted her mother and supported Vincent’s version of events. Vincent reappears in the newspaper on 23 November 1904, when he again found himself in court, having been discovered sleeping rough with another boy called Thomas Hamnet. Kilkenny gave evidence. He said Vincent had not lived with him for ‘more than a fortnight the past nine years’ and claimed that he had ‘no earthly control over him whatsoever’. It was clear that Kilkenny wanted shut of him. The court obliged. Vincent was sent to an Industrial School. There was no sign of the loving mother on this occasion. Vincent was not alone in falling foul of the law. His eldest sister, Catherine, was convicted of theft in September 1913, along with her half-sister Winifred, who was placed on probation for three years and sent to a ‘home’. Of Mary Ann’s seven children, only Bridget and James seem to have survived their upbringing unscathed.

In the Bosom of the State

Industrial Schools were established by Act of Parliament in 1857. The act gave magistrates the ‘power to sentence homeless children between the ages of 7 and 14, who were brought before the courts for vagrancy’. These powers were strengthened by an amendment in 1861, to include:

‘Any child apparently under the age of fourteen found begging or receiving alms (money or goods given as charity to the poor).

Any child apparently under the age of fourteen found … wandering and not having any home or visible means of support, or in company of reputed thieves.

Any child apparently under the age of twelve who, having committed an offence punishable by imprisonment or less.

Any child under the age of fourteen whose parents declare him to be beyond their control.’

In Riley’s biography it is claimed that he was first sent to a local industrial school, the Staffordshire County Industrial School for Boys, at Werrington, and then to the Bishop Brown Memorial Industrial School for Roman Catholic Boys in Stockport. Glen’s biography has the same attitude to dates that vampires have to garlic. It may be possible, when (and if) archives eventually re-open, to discover exactly when Vincent was incarcerated in one or both of these institutions. But we do know where he was, more or less, between 1910 and 1912. He was in the Royal Navy.

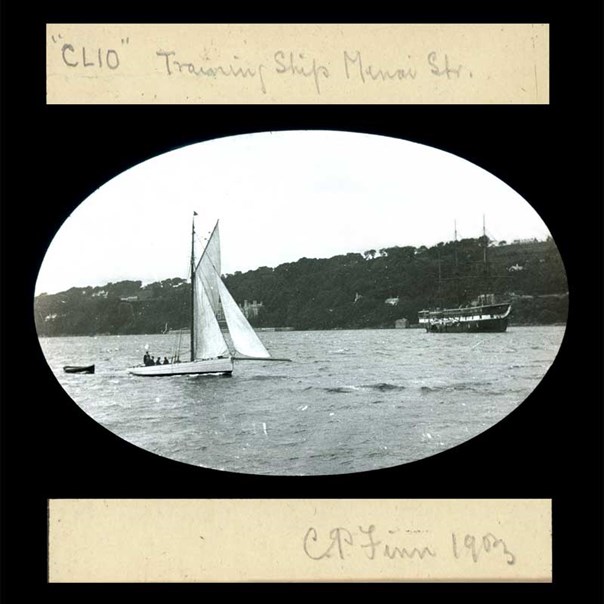

The credit for launching Vincent on a naval career was given by Glen to Bishop Brown’s School. According to him, Vincent was sent to the naval training ship, HMS Cleo (properly Clio), laid up in the Mersey.

Above and below: HMS Clio

Image courtesy of www.cpfinn.com

The story of this ship has been told by Emrys Wyn Roberts. HMS Clio was never in the Mersey, but in the Menai Straits. Again, we do not know for certain if and for how long Vincent was aboard this ship, but his naval career subsequently is documented in the UK Register of Seamen’s Services, 1900-28.His naval record first shows him at the RN Training Establishment, HMS Ganges II, an institution with a somewhat brutal reputation, based at Shotley in Suffolk. On 19 August 1910 the Sentinel reported him as being absent from the Ganges. He was remanded by Hanley Police Court to await a naval escort. From 30 August 1910 until 2 February 1911, he served on HMS Caesar (a Majestic Class, pre-Dreadnought battleship). On 3 November 1910, which the Royal Navy thought was Vincent’s 18th birthday (but was actually his 19th), he signed on for 12 years’ service. From 3 February until 5 June 1911 he served in HMS Victorious (another pre-Dreadnought battleship). (He is shown in the 1911 Census on board the ship, off Torquay.) From 6 June until 11 September 1911, he served in HMS Devonshire (a Devonshire Class armoured cruiser).

HMS Devonshire (IWM Q21159)

This was followed by transfer on 12 September 1911 to the RN Shore Establishment, HMS Vivid I (Vivid I was the Seamanship, Signalling and Telegraphy School in Devonport). He remained there until 28 December 1911, when in naval parlance he ‘ran’, that is deserted. He was returned to the navy on 6 March 1912 and sentenced to forty-two days’ detention. On 23 April 1912 he was discharged on the grounds of what appears to be ‘suicidal insanity’. He spent the period 3 May to 18 June 1912 as a patient in the Staffordshire County Asylum, Cheddleton, in the Churnet Valley. He was soon back in the courts, making three appearances in 1914, the final one in July, charged with assault (on a woman). Riley’s naval career was mixed, with two periods of absence without leave, but his conduct was also rated as Good or Very Good at times and someone must have thought it worthwhile to send him for technical training at HMS Vivid I. His Royal Naval service was, perhaps, the one chance Vincent Riley had to join mainstream society and lead a worthwhile life. It was to be downhill all the way from then on.

The Long Finis

After the war the next important event in Vincent’s life was his marriage. This is usually omitted or elided in most accounts and his wife is not even given the dignity of being named. She was Gertrude May Thacker, a general servant, who hailed from the village of Mucklestone, near Woore, on the Staffordshire/Shropshire border. They were married on 15 May 1921 at the Sacred Heart R.C. Church, Hanley. Their daughter Kathleen was born later in the year. One of the persistent features of the treatment of Vincent Riley in the local press, and in much local memory, is to regard him as essentially harmless, a character, whose roguish ways wove a bright thread in the dull tapestry of life, a ‘free spirit’. He may have become harmless in later years, but he was not always benign. On 12 October 1923he was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment for being drunk and disorderly in Stafford with another month for assaulting P.C. Davies.‘ P.C. Cooper stated that he saw the prisoner in Gaol Square, Stafford.

Gaol Square, Stafford. Image courtesy of www.tuckdbpostcards.org

He was drunk and using bad language towards his wife. Cooper requested him to go away, but he became abusive and violent.’ On 20 March 1925 he was sentenced to another month’s hard labour for being drunk and disorderly in Stafford. ‘He was shouting and making himself a general nuisance. He had his wife and little child with him.’ Inspector Turner stated that ‘the man had a terrible record, having 50 convictions against him chiefly for drunkenness, stealing and assault’. It is little wonder that the marriage did not endure.

The pattern of Vincent’s life was now set - recurring bouts of imprisonment, usually 28 days at a time, mostly for being drunk and disorderly. He seemed to accept his situation philosophically and one of the things about him that does elicit admiration is his lack of self-pity. He had given up on ‘normal’ life, especially after becoming a meths’ drinker. Imprisonment was the price he paid for the way he had decided to live. Ironically, it is these regular periods of incarceration that probably extended his life and, as Glen argues, the police were the only institution to come well out of Vincent’s story, usually treating him with humanity and forbearance.

Does any of this matter, other than to ‘Disgusted, Stoke-on-Trent’? I think it does. My problem is not really with Vincent Riley, a sad, even tragic figure, though I doubt he would have seen himself in these terms. It is with those who persist in elevating Riley into something he was not and in the face of all the evidence to the contrary. A friend of mine who expressed himself somewhat forthrightly about the remembrance of Riley as a loveable rogue, when he was ‘an aggravated burglar, thief, swindler and fraud’, was accused of being ‘unkind’. The truth often is, alas. There are enough true heroes in the Great War worthy of our remembrance, without having to fake one. And there were enough men who were genuinely traumatised by their experiences. We should not allow the memory of their suffering to be ‘stolen’ by someone whose misfortunes began long before the war in an uncaring, poverty-stricken, alcoholic and dysfunctional family from the influence of which he was unable to escape.

John Bourne

(The views expressed in this article are mine alone, but I could not have written it without the help of Su Handford, Dr Alison Hine, Andy Johnson, Dr Bill Mitchinson, Mick Rowson, Craig Suddick and Levison Wood.)

Addendum

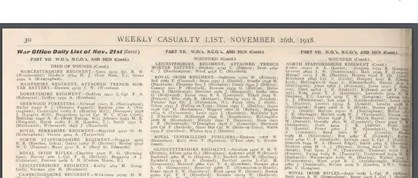

I was recently asked by an old friend and former student, Ian Houghton, to help him research the Great War service of a North Staffordshire Regiment soldier, Ernie Woolley MM, the father of a friend of Ian’s mother-in-law. During his researches, Ian came across the British Weekly Casualty Lists, available online at the excellent National Library of Scotland. These lists were news to me. As Ian was working his way through them, looking for his man, I asked him to keep an eye open for the name Riley/Kilkenny/Killkenney. Ian duly found the name of the ‘worthless scamp’ in the Weekly Casualty List, published on 26 November 1918. Naturally, given Vincent Riley/Kilkenny/Killkenney’s history, this was not quite straightforward. He is shown among the list of North Staffordshire Regiment wounded as ‘Kilkenny 201738 P. (Hanley)’.

The regiment is correct, the surname is the one Vincent Riley was known by in the army, the service number is correct, the town of origin is correct. That just leaves the incorrect initial, ‘P’, easy enough to misread or misheard for ‘V’. I am confident that this is ‘my’ man. Does this information help in identifying when Vincent Riley/Kilkenny was wounded? Possibly.

The view I stated in ‘”A Worthless Scamp”: The Great War of Vincent Riley’ is that he was probably wounded in the spring of 1918. He was not mentioned in the local press as being a ‘wounded soldier’ until 5 July 1918. The wound he suffered was a serious one, given the rate at which his disability pension was paid. It is unlikely that he returned to the army after his wounding. He was in prison until 9 August 1918. When we again find him in the local press, during another court appearance in April 1919, he was still being described as ‘a soldier in hospital uniform’.

Ian explained that the set of casualty lists on the National Library of Scotland website is incomplete. List No. 63, covering 7-12 October 1918, is missing entirely and list No. 48, covering 24-29 June 1918, has some pages missing. If Riley/Kilkenny was wounded in April 1918, as I suspect, his name is more likely to have featured in list 48 than in list 63. That said, it was in list 69 (18-23 November 1918) that Ian found him, which perhaps raises two possibilities: that there was an extraordinarily long delay between his wounding (if he was wounded in April) and its eventual listing, or he was wounded twice in 1918.

Personally, I think the latter explanation is unlikely. But we can now be confident that Riley/Kilkenny was wounded in 1918 and not before.

J.M. Bourne

Ian Houghton

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.