Addison Barnes Perrott Hadden MC - South Irish Horse in the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Addison Barnes Perrott Hadden MC - South Irish Horse in the First World War

For many years, I have had in my sewing basket the buttons from the uniform of the South Irish Horse and the cap badge of the Officer Training Corps (OTC)from Trinity College Dublin.

These were given to me by my grandmother with reference to my grandfather, “who had received a medal” in the First World War. She did not describe what he had done. Many years later, much more recently, when my mother (his daughter in law) died, his medals and some letters came into my possession.

These were given to me by my grandmother with reference to my grandfather, “who had received a medal” in the First World War. She did not describe what he had done. Many years later, much more recently, when my mother (his daughter in law) died, his medals and some letters came into my possession.

It was always something that I intended to organise but was prompted to do so by meeting a family friend who is an historian with an interest in the two World Wars. He told me that one medal was the Military Cross and helped me research the South Irish Horse. This motivated me to be proactive and investigate further, having not known my grandfather, but heard family stories. I have been helped putting Addison’s history together by using written histories, emails and verbal conversations with cousins and family.

Introduction to the Hadden Family

Addison was born to a Methodist family in Southern Ireland in 1895. He was the youngest of 8 children and was brought up in Springfield House in Wexford, south east Ireland. His father, George and his mother Hannah Mary ran a successful Drapery business, “W & G Hadden.” The business started in Wexford by George’s parents in 1858 and expanded to Dungarven first and then to Carlow.

The eight children were George, Isabelle, Richard, William, Frances, Eileen, Marie and Addison. Addison was the youngest. From family stories and looking back into the past, they seemed to be a close knit family. The limited photographs, show Addison, the youngest, often smiling and his letters, to his sister Frances were written in a humorous or tongue in cheek way.

Above: The Hadden Family outside Springfield House. Addison is on the bottom step, right hand side.

George was the eldest and lived the longest until he was 92. He is still remembered in Wexford for his involvement with the Wexford Opera and the Old Wexford Society, an historical society. He was also awarded the Freedom of the City of Wexford as an award for all he had done for the city. He must have had a very interesting life, but I only remember visiting his house, to meet him and Aunt Helen, his wife, on a few occasions. It did not seem so interesting then as a young child. He had a long white beard and was very tall. He trained in Edinburgh to become a medical doctor. Richard and Marie also trained to become doctors in Trinity College, Dublin. George served in medical missions in central China. He had an association with Yale university and so in the first world war he gave medical care in Siberia in 1917-1918 as part of the services offered by the American Red Cross. He ended his work in China in 1933 he returned to Wexford.

Richard served with the Royal Army Medical Corps in Gallipoli and Palestine; He was awarded an MC for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on October 8th 1918 at Tenbrielen [Belgium] he went through heavy shelling to attend to a wounded man and by his prompt action and disregard of danger, probably saved a man’s life.” Sadly, Richard died in Yunnan province of Typhus in 1930. In 2015 a bible that had been found on Hill 60 in Gallipoli, dated 22 August 1915 was returned to one of the Hadden cousins, Avril Hogan, by Tim Molloy, the grandson of the man who found it on the centenary of that date in 2015.

Marie was a junior doctor in Dublin and subsequently married the harbour master in Shanghai. Frances worked as a nurse in Dublin during the First World War before going back to Wexford to look after her parents. She appeared to be very close to Addison and may have been the person who kept his letters safe and hence how now, they are in my possession as my grandmother sorted out her flat on her death. Eileen and William both worked in the Drapery business and started the shop in Carlow.

Addison was educated at the Tate school in Wexford and then in Wesley College in Dublin, a Methodist boarding school. It appeared that he then returned home to help run the family business.

The Political Context in Ireland

In 1912 the Third Home Rule Bill for self-government of Ireland was formally tabled again after the removal of the Lord’s veto in 1911. It was approved. So, in 1914, Home Rule would have become a reality and only a matter of time before the Irish had its own parliament.

This was not popular with the Unionists in the North of Ireland, where the population was mainly Protestant, unlike the South which, was mainly Catholic. The Unionists called Home Rule “Rome rule.” Edward Carson convened a meeting to sign The Ulster Covenant to use “all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy”. In 1912 the Ulster volunteer Force Militia [UVF] was formed of almost 100,000. The Irish Volunteers [IVF] nationalist militia formed in response, in 1913 to support Home Rule at all costs, it then seemed that the Home Rule would lead to bloodshed and civil war in Ireland. However the IVF had much greater difficulty obtaining arms and ammunition.

The course of history was changed for Ireland and the world with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo. This then triggered alliances between countries and War was declared, the First World War.

On 18 September 1914 Home Rule was granted to Ireland by royal assent, however the implementation was immediately postponed until the end of the war, or for one year, if the war was short.

The British began to mobilise the British Expeditionary Force which was composed of 86,000 officers and men and sent them within days to France. They then marched towards the German army in Belgium, towards the first Battle of Mons. Initially the men sent were experienced, but later came others who were volunteers with far less training. Irish men had already been serving in the British army, but at the start of the war many of the IVF and UVF also signed up to join.

John Redmond, Irish parliamentary Leader appealed to the IVF members to join the British Army and join the war effort. There were posters displayed to try to recruit men who joined for different reasons; some as Unionists with a common cause with the British Army, others felt it important to support the British, to show that after Home Rule they would not be anti-British. Some joined as Republicans to support smaller nations such as Bosnia and Serbia to achieve self-determination as they hoped Ireland would be able to do. Others to earn money for their families, or they saw the war as an adventure to get away from their monotonous life in Ireland. It was also thought the war would be short lived. Little did they know the horrors that they were about to experience.

Those Irish volunteers (some 10,000) that declined to serve the Crown and the militia became influenced by others such as the barrister, teacher and poet Padraig Pearse, who was convinced that there was a need for armed rebellion against British Rule and that the war was an ideal opportunity for such a rebellion in Ireland. Estimates of how many Irish men fought in the First World War vary, but it is generally accepted that around 200,000 soldiers from the island of Ireland served over the course of the war, with over 50,000 already enlisted in the British Army

Addison Hadden in Ireland; OTC and Commission to South Irish Horse

War news travelled back to the British and Ireland from the start. The catastrophic figures of wounded and killed did not seem to deter others from signing up to join. More signed up in 1916 than at the beginning. Conscription was compulsory in the UK after January 1916 but not in Ireland. Addison appears to have decided to sign up in1916 - he would have been 20 years old. Trinity College, (Dublin University) ran an Officers Training Corps (OTC) to give military training to students so that they could apply at short notice for a commission with the army as officers. The OTC had been formed in 1908 with close links to the Territorial Forces, an army reserve that had been created the same year. OTC officers would have Territorial Force commissions and it was hoped would solve the problems of the shortage of officers in the army.

OTC cadets did not take the oath of allegiance and could not be called up to the British army proper. Although the OTCs were military organisations, controlled by the war office, individuals would have to apply in the same way as anyone else for full time or overseas service. Signing up for the OTC, also meant that there had to be an agreement to a certain amount of annual training and at least 3 years of service. Certificates of training with the OTC were of benefit to anyone applying for the civil service, colonial service or army. Those who joined were undergraduate or postgraduate students of Trinity, the numbers increasing considerably when the First World War began. Although it had been opened in the past to “gentlemen” that unit commanders considered suitable and college authorities were willing to admit, from August 1914 the numbers of non Trinity students increased dramatically. Maybe it was for this reason that Addison considered joining and he presumably needed appropriate referees, which, may have taken some time to organise.

Addison joined Dublin University (Trinity College) Officers Training Corps (ASC Unit) on 1 March 1916. He went on to finish his training with the OTC in August1916 and obtained a commission with the South Irish Horse. The South Irish Horse (SIH) was a unit of the Special Reserve. It provided a mounted form of part-time soldiering. It was mobilised on the declaration of war. The SIH wore a distinctive green uniform.

On 7 April 1916, Addison wrote from Dublin saying,

“...we were all asked to attest today, so about 10 of us marched down to the recruiting office. I was medically examined, but they had not time to swear me in so I am to go back for my ‘shilling' on Monday”

He also said, writing to his sister that he hoped to see her at Easter in Dungarven. This is followed up by a letter eleven days later saying that he was

“...up in front of an old general and as far as I know we all passed”.

He said he was hoping to move onto the Curragh.

Addison went home for a holiday to Wexford at Easter 1916 for about 10 days. Had he not done so, he would have had a very different experience, it was also the week of the Easter Rising.

The Easter Rising, or Easter rebellion was an armed insurrection in Ireland which started on 24 April 1916. It was started by a group of Irish nationalists proclaiming the establishment of the Irish Republic and was staged against the British government by seizing prominent buildings in Dublin and clashing with British troops. By the end of a week there were two thousand dead or injured.

In May, fifteen of the leaders of the rebellion were executed by firing squad, in Kilmainham Gaol. More than three thousand people, suspected of supporting the uprising, directly or indirectly were arrested and some imprisoned without trial. Although initially there was little support amongst the Irish people for this uprising, the British response changed their opinion, and the executed leaders were subsequently considered to be martyrs. General Maxwell controlled the British Troops in Ireland (many of whom were Irish waiting to be deployed abroad). However, the swiftness of the execution of the leaders and lack of convincing trial caused a change in public opinion and is thought to have eventually led to the treaty in 1922 establishing the Irish Free State (and then afterwards the modern Republic of Ireland).

Neil Ferguson’s book “According to their Lights” describes in vivid detail the events of the Easter Rising and the involvement of the rebels and British troops. He also describes the OTC defence of Trinity College Dublin. Trinity had arms stored and there was a concern that the rebels could raid these. Addison was training with the OTC at this stage but had taken 10 days leave to go back to Wexford.

Another family story is that Marie returned to work in the Adelaide as a junior doctor at the end of this week, close to Jacob’s Biscuit Factory At some point, she was in a bathroom of the hospital residence, and a bullet came through the wall! She was unhurt.

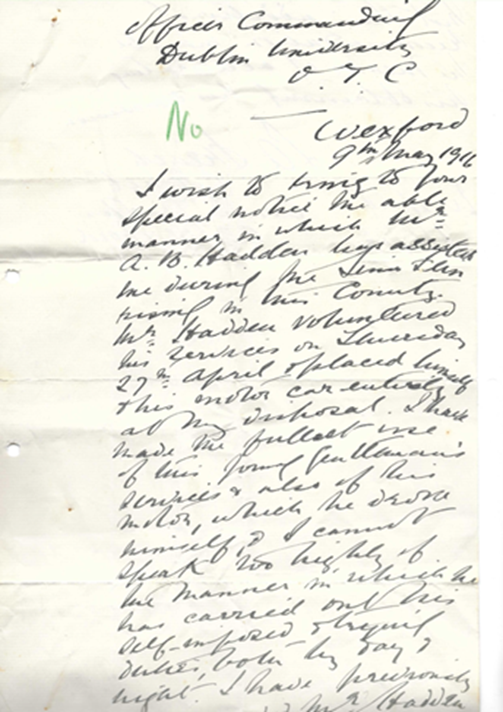

Although the rebellion was supposed to be a national one, for various reasons this did not happen. There was a smaller simultaneous uprising in Enniscorthy, a town close to Wexford, when local units of the Irish Volunteer Force took control of the town on 27 April 1916. A retired British Colonel living in Wexford, Colonel George Arthur French, was called to resolve the situation. He was considered to have managed this well, as unlike in Dublin, there was no bloodshed. He had a conversation with the rebels and treated them with courtesy. He asked them to stand down because the leaders had done so in Dublin. As the rebels in Enniscorthy did not believe him, he offered them safe military passage to Dublin to confirm these events, by meeting with Padraig Pearse in Arbour Hill Barracks Dublin. By 1 May they had a written surrender. I found a letter amongst my collection from Colonel French written on 9 May 1916 to the Officer Commanding Dublin University recommending Addison for a commission after providing his help, during the Enniscorthy uprising. Addison had lent his car to the Colonel on 27 April 1916.

Above: the letter from Col. French

After the Easter holiday, Addison returned to Dublin from Wexford and wrote to his sisters on his return on 12 May 1916 saying “that the streets were quiet when I returned and that Sackville Street [now O’Connell Street] could easily be a Belgian or a French city”. Only Nelson’s Pillar was recognisable after the Easter Rising.

The report of the Officer Training Corps on completion of his training also mentions the Sinn Fein Rebellion saying that Addison “Has completed an intensive course of training satisfactorily. Bearing Excellent. Word of command good… Should make a good officer. Took an active part in the suppression of the Sinn Fein Rebellion”. His rank is recorded as Corporal and training of five months.

On completion of his training, he was then enlisted into the South Irish Horse at Dublin on 28 August and into No.2 Cavalry Cadet Squadron on 1st September. He went to France on 6 January 1917 and there is a record in the war diaries that he and his Wexford friend Ferguson were with A Squadron. Ferguson was then sent to B Squadron.

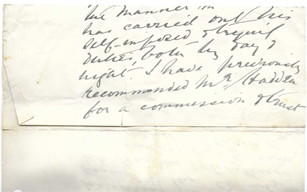

Above: a studio portrait of Addison Hadden

Addison Hadden in France

Once in France, he regularly wrote home in the first year. This was the main mode of communication and reading them so many years later, I am surprised how frequently they were written, sometimes daily. It appeared that in the first few months of his time in France, there were lectures and training of men and horses. His letters contain very little detail of the surrounding countryside or life in general. They tended to relate to the more mundane, food and clothing. The letters were censored and the first few may never have been sent, as he had put his address on them, the content of the letters could not have detailed information. Most of the letters were directed to his parents, mainly his mother and are really to reassure her that all was well. The letters were written on tiny scraps of squared or lined paper in pencil. Early on, there seemed to be sufficient supplies of paper and post seemed to go regularly at 4 pm in the evenings. Later on, towards the end of the year, that seemed to change when there was difficulty obtaining paper. Many of the letters were incomplete as if the second page has been lost. The war diaries also have very little information as to the movements and actions of the regiment until September 2017.

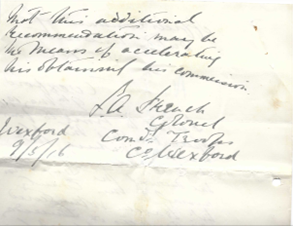

Above: one of Addison’s letters to his mother

Addison’s letters comment on the cold and the snow and he asked for further clothes, (drawers and vest) particularly as “somebody is on the lifting game”. The winter of 1916-1917 was the worst in European memory and his letters mirror this fact as there was snow into April. He mentioned St. Patrick’s Day, which was a holiday for the regiment and said he wished he had gone with some of the men to another Irish Regiment to celebrate the day 5 km away as he might have missed out on some of the fun. This was recorded as a holiday in the war diaries.

His letters record receipt of many presents; food such as beef, cake, oxo and sweets, but also Shamrock, boots from Gibson’s, pyjamas, underwear and body armour, which he eventually sent back as it was too heavy to carry. He was always pleased with the presents but eventually becomes concerned that the family may be leaving themselves short and so told his mother it was not necessary to send food to him. It did not appear that she took this advice.

On 9 April 1917 he remarked that on the day before he had “been up the line and never seen such devastation in my life.” He also missed his wristwatch that he hoped could be mended before they moved again as it was broken in a football match. The war diaries finish in April and did not restart until September 1917.

He rarely commented on any of the work he did, but in May he said he had been “on a detached post for 4 days with 12 men and two machine guns. We are not in the trenches so don’t worry. The job is a nice one and I only hope I am left on it for some time.” He did indeed continue to do this as the weather again improved. He visited his friend, writing in a letter on 13 May 1917 “Ferguson is a long way away now, but I managed to get over to see him yesterday. He is looking very well and has got a nice job. I went by road and it was great fun trying to get there in motor cars and lorries”.

On 28 June 1917 he said that he was being transferred from A Squadron to F Squadron. He also said he had lost his identification disc, so they were not to worry if the War Office contacted them, having found it. His friend, Ferguson, had also been transferred and was sharing the same tent with him. He took leave for about ten days in August and went back home, feeling much better after he had done so.

In July, as part of the re-organisation of mounted Yeomanry regiments by the Army Council, notice was received that the Regiment with the 1st Irish Horse was to be dismounted and reformed as an Infantry Battalion. When he returned from his holiday, by 1 September they were training to become Infantry. The horses had been sent to Marseille to travel to Egypt where they would be used. The Regiment became the 7th (South Irish Horse) Battalion Royal Irish Regiment.

The war diaries suggested that September and October were taken up by training: “Lewis Gun, bombing, squad drill, musketry, platoon drill, bayonet fighting, physical training”. Two officers and seventy NCOs who had taken the horses to Egypt returned. The war diaries were quite full with almost daily entries, as the troops moved to Ervillers. They continued to train and repair trenches, and wiring. There were very few letters over this period of time.

In January 1918, he was hoping for further leave. The war diaries said that they were in Ronssoy. The diaries said that the village was shelled on 2 January from 6-8pm and again at 9-10 pm with retaliation at 10.15pm. He did not mention this at all in his letters but reassured his parents all was well.

On 7 February 1918, General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough KCB KVO visited and presented medal ribbons to officers and other ranks. He was the GOC (General officer Commanding) of the British 5th Army. Addison said in his letter of 14 March that he was sending a parchment which, entitled the holder to wear a green diamond on the right sleeve. He said“its not worth much”.

21 March 1918 was the first day of the German Spring Offensive, a furious and mass onslaught launched in an attempt to win the war. These assaults hammering the British and the French positions for scores of miles all along the trench front lines were known collectively as the Kaiserschlact to the Germans; and to the Allies as ‘The Ludendorff Offensive.’ Addison was stationed in Northern France, on the Western Front.

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig British Commander-in Chief, records in his dispatch:

“At 440am on 21 March 1918, a vast volume of fire from the powerful German artillery burst forth on the fronts of 3rd and 5th Armies, from almost 6,000 guns – in a morning of dense fog, which mingled with the smoke and gas shells. The weight of the bombardment, added to the fog, meant that the Battle Zone was half obliterated and largely blinded from the first; there was also an absolute breakdown in communications. There was heavy fog coinciding with the German assault which overwhelmed and destroyed the British army.”

Addison’s battalion, the 7th Royal Irish Regiment, would have counted some thirty commissioned officers and 670 to 700 NCOs on 20 March. Just one officer and around fifty other ranks were left to answer the roll call by the day’s end, as bad if not worse than most severely mauled British battalions on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Somme offensive. The events were catastrophic for the British army and led to Haig removing Gough as a scapegoat for the disaster. Apart from September 1914 this was the closest the British and the French came to losing.

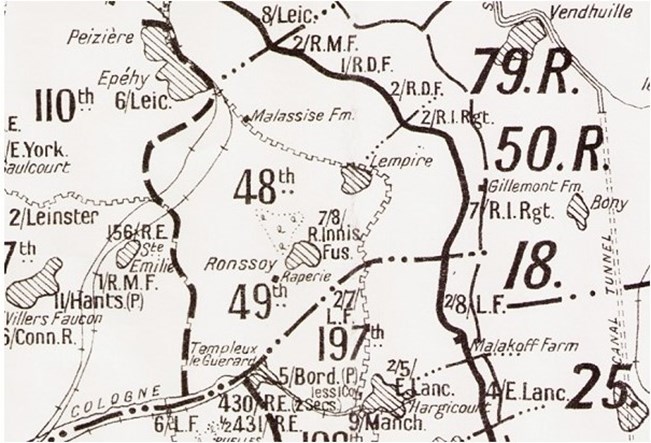

Above: 21 March 1918 – showing the position of 7th Royal Irish Regiment. Image: the longlong trail

Addison was both unlucky and lucky to be captured, as he then survived the war in a prisoner of war camp. The Army Act warned of the death penalty for those who “shamefully” abandoned their position or person to the enemy. The legislation dictated that all captured British Servicemen would be subject to Courts of Enquiry on their repatriation. After the war Addison wrote his report below of the day’s events on 21 March 1917 to the Board of Enquiry and this appears also to be the reason for his Military Cross.

“On the night of the 20/21st Marchmy battalion having assumed “battle positions” was left in charge of the S.O.S post of 20 men in Quillemont Farm 40 yards from the German line. [The South Irish Horse say the cat post.] My orders were to send up S.O.S rocket in the event of advance of the enemy and then rejoin my coy at the “Red Line” about a mile to the rear. I had a telephone to Battr, but the wires were not buried. The enemy bombardment commenced about 4.30 am, at 5 am I felt certain that he intended to advance. I therefore sent all but 6 of my men back to reinforce “Duncan Post” as I felt my work could be better carried out by a small number. The enemy used H.E, gas shells and we supposed smoke shells, as the natural fog became so thick that we could not see more than 10 yards. Barrage slackened about 9.30am.

According to our information we had 2 hours to wait from lifting of barrage until enemy advanced, so as to let the gas clear away. I therefore left Sergt. Leary in charge of the S.O.S post and went to signallers dug out to send them to Duncan Post” Their wires had been cut in barrage and they were therefore useless to me. I was not 3 minutes away from S.O.S post but on re-entering trench found myself surrounded, as trench was held by Germans. I learnt from Sergt. Leary, that he had sent up an S.O.S rocket, but could not see it burst as fog was so thick. My servant and I managed to get out of the trench under cover of fog and succeeded in reaching and warning Duncan post of enemy advance.

The telephone wires from Duncan post were also cut, so I set out again hoping to warn Battr. We were both suffering from shortness of breath, owing to the gas we had inhaled during the morning. We were captured again in a trench leading to the Red line” but succeeded in getting away a second time. On nearing Red Line I found Germans already attacking it so turned into Sart Lane, hoping to find it still holding out. This was also held by the enemy and I was captured again. Fog was lifting and I found it impossible to escape again so was eventually sent under escort into German Line.’

Addison Hadden as a Prisoner of War

After 21 March Addison was then taken as a Prisoner of War (PoW) to Holzminden. He was reported as missing initially but later his parents were contacted to say he was in captivity. There is a letter from W.J.Mc Connell C.F. on 22 April 1918 to Addison’s father, George saying, “I cannot tell you how delighted I was to hear today from Major Roche Kelly that your son had escaped with his life and that Captain Watts was in a like fortunate position. I did not tell you in my last letter that while those men were waiting for your son at Sart Farm they heard revolver shots and bombs where he had gone in and I fear that I was sharing in the common belief when I thought that the chances of hearing of him again as being alive were very small. I am glad that agreeable surprise awaited us”.

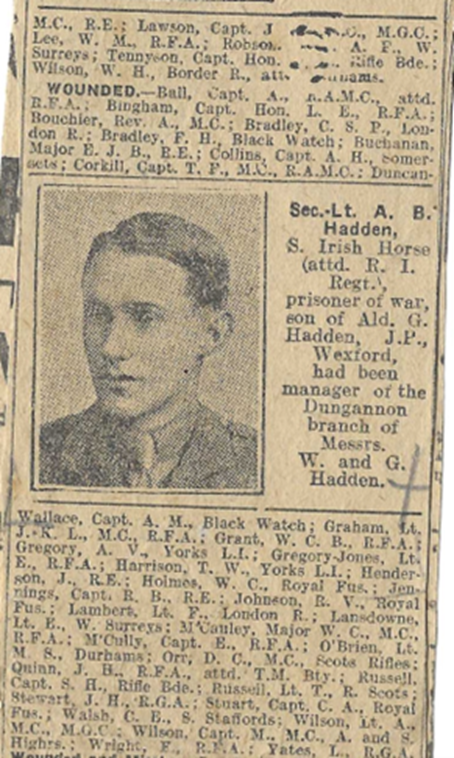

Above: A newspaper report of Addison as a prisoner of war

To be captured as a prisoner must have been very frightening. There was a problem of communication between the two sides and a deep distrust of each other’s motives. There was also danger with the physical transition to the camps at the mercy of the enemy. For some capture led to feeling shame, ignominy and guilt- of letting down their comrades, their regiment, their King and country.

Attitudes changed in the eighteenth century to prisoners of war with the primary purpose of capturing service men to incapacitate them from fighting, the captor being legally and morally bound to care for the captives. The First World War marked a watershed with the scale and, range and duration of war captivity. Estimates are that the number of servicemen captured over the globe was 9 million. The greatest number of 2.5 million were incarcerated in Germany. Intriguingly, less is known of the Prisoner of War camps in the First World War than those of the Second.

Later in the war, there had been more propaganda about the mistreatment of PoWs in German camps. Initially all nationalities were mixed, but later this changed to keep prisoners within their own nationalities. The standards of care were different depending on the rank of the soldiers with living conditions better for officers than the troops. Diseases such as typhus (carried by lice) and cholera appeared very quickly with close confinement of the prisoners.

Holzminden was in Lower Saxony and a large camp for officers, (Offizierlager or abbreviated to Oflag). It held 500-600 prisoners. It opened in September 1917 and closed when the last of the prisoners were repatriated. There were 100-160 other ranks, designated as orderlies.

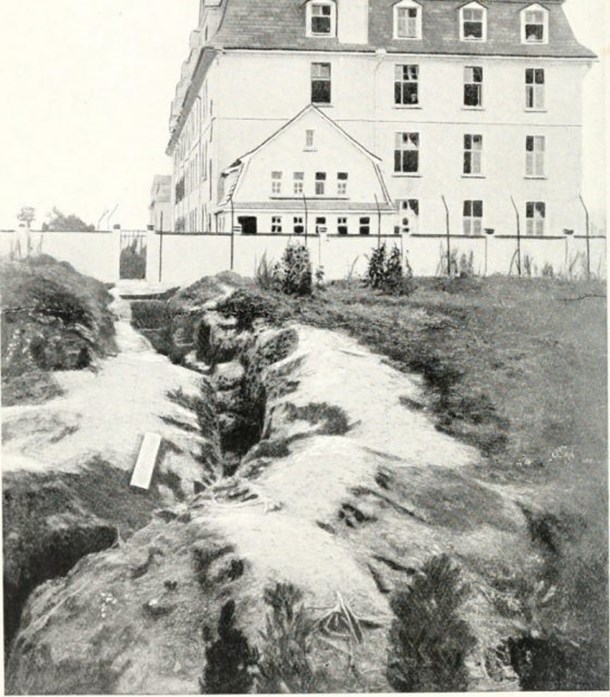

Above: Holzminden Camp

The Kommandant after the first month was Hauptmann (Captain) Karl Niemeyer. He had lived with his twin brother for 17 years prior to this in Milwaukee Wisconsin but returned to Germany in 1917 when the USA entered the war. He spoke a strange American English and the prisoners constantly ridiculed him. His regime was arbitrary and punitive with reported allegations of ill treatment including solitary confinement of prisoners.

The prisoners suffered from a poor diet as there was an economic blockade of Germany and there was little food for the civilian population, let alone much to spare for the incarcerated enemy soldiers. The Hague Convention of 1907 made the captor responsible for food to maintain their physical health. However, the only practical way to feed large numbers, was with soups and stews. These had very little substance to them and would be augmented with black bread and potatoes. The coffee was a substitute made from burnt acorn coffee. Most of the British prisoners were not used to a German diet, heavy black bread, raw herring, coffee, sauerkraut. They were more used to white bread and tea.

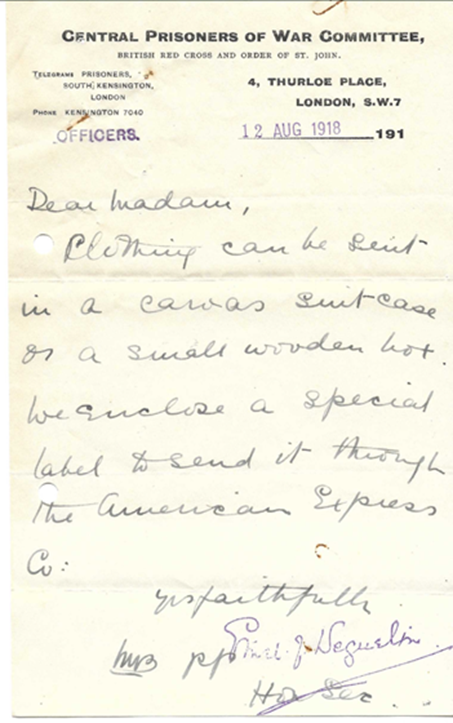

Basic PoWs’ need of clothes and food could be sent from home or delivered by international bodies. The social background of the prisoner might determine what was sent. From 1916 personal parcels were curtailed in an effort to centralise the PoW relief system when The British Red Cross and Order of St John took control over the administration, packing and sending parcels by the creation of the central prisoner of war committee whose depot was located at 4 Thurloe Place London. This is evident within the correspondence related to Addison. Supplies from home also allowed some negotiations in the camps, as often their food was better than their captors.

Holzminden was the scene of an attempted escape in July 1918 when Addison must have been at the camp. The entrance was hidden underneath a staircase in the orderlies’ quarters of Kaserne B. It took 9 months and in the early months, the excavators had to dress in Orderlies uniforms, as officers were not allowed in the orderlies’ quarters. Some of the equipment that they would require on escape, high energy food, maps, compasses came via the parcels. Eighty-six officers were waiting to escape, but only twenty-nine managed to escape as the tunnel (it was 60 yards long, 18 inches wide) collapsed. Of the twenty-nine escapees, ten managed to get to the Netherlands and Britain.

Above: The escape tunnel at Holzminden

After the escape there was a response by the Germans of collective punishment. The SBO (Senior British Officer) of the camp asked for organised misbehaviour: not attending roll calls, no salutes, no observance of orders and swaggering with hands in their pockets. It appeared on the surface that discipline had collapsed. Discipline within the camps was very important for the Germans to maintain a stable camp. The British behaviour forced Niemeyer to negotiate with the SBO to improve the situation and also stop the collective punishment.

Letters to and from the Oflag were allowed but limited in the number and amount of correspondence. There appeared also to be self censorship of letters. Addison had to sign a card on arrival to agree not to try and escape and “not commit any acts that are directed against the safety of the German Empire”. Once Addison’s parents knew where he was, they contacted the Red Cross to find out how parcels could be sent to the prisoners.

Above: the response from The Red Cross

Addison’s letter of 29 March 1918 said that he had been a POW since 21 March 1918 and that he was reasonably comfortable. He asked for specific items of food. He did not complain of the food, [surprisingly] saying “the food he received in the camp, although plain was good”.

The main problem for officers was the monotony, boredom and deprivation of food and freedom in the camps. Football, hockey, tennis, concerts debates and reading were tried to relieve the tedium.

Only three letters from his time in Holzminden have survived, all of which are written in tiny, neat writing filling the whole of the page, written in March, October and 5 November 1918 when he said “there is a lot of subdued excitement in camp for the last month or so and I am finding it almost impossible to do any work or reading. The events of the day are letters, parcel lists and the papers”. He talked of being in a dormitory of three hundred men; twelve in a room. “Do you know, I envy you being all alone in Springfield”

Above: Addison’s letter of 5 November 1918 to his parents

Learning of the Armistice filtered through to the POWs in different ways. In Addison’s last letter he appears to know that something is about to happen. At Holzminden Hauptmann Niemayer changed his aggressive behaviour before he disappeared. He was subsequently named as a German War Criminal but was not charged at the Leipzig trials.

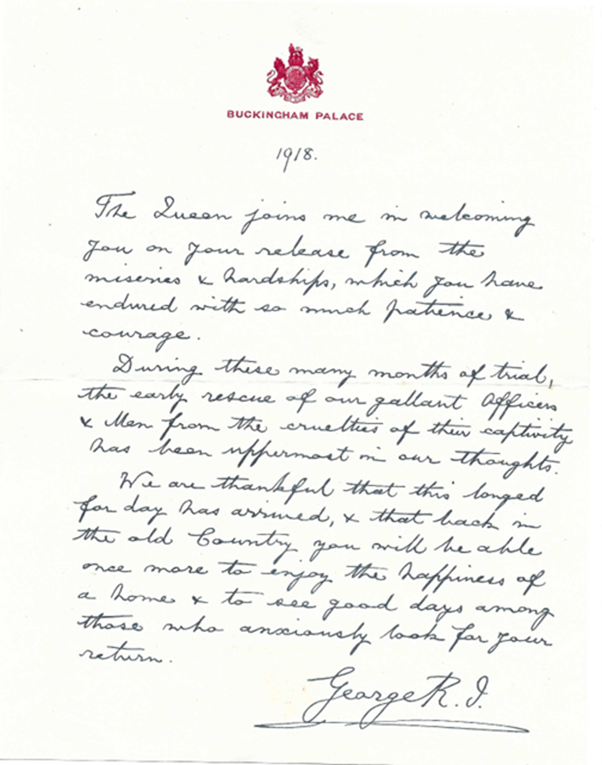

Returning home was reflected in food, clothing and medical care that were heaped on the men. On the boats home they got 1/4lb of toffee, 1/4lb of chocolate, 20 cigarettes and 2oz of tobacco for a pipe. Addison appears to have arrived in the UK before being transferred to Ireland. There was a telegram of 14 December 1918 written to Frances, saying that he had “just landed, hope to get home in 4-5 days.” He also received a letter from the King, thanking him for his services.

Above: the letter from the King, sent to all returning prisoners of war

Another letter written from Wexford to Frances, his sister, in April 1919 stated that he was about to be demobilised. There is a letter from the War Office on 19 March 1920 to confirm that approval had been given to the resignation of his commission in the Special Reserve of Officers. There is another one that was not dated which said he had been awarded the Military Cross and this would be sent on to him in Ireland.

Addison and his brothers, George and Richard, survived the war. I am sure their parents were greatly relieved. However other Haddens were not so lucky. He mentions an Uncle Willie, who was probably his father’s brother. In 1917 he mentions him several times and says he sounds to be unwell. Later he also mentions that Uncle Willie has “been gassed and I hope he is now doing alright. All his luck seems to have left him lately.”

Captain Henry Arthur Giles Hadden a medical doctor with the RAMC and Captain died on 30 August 1917 aged 49. (A cousin of Addison whose father had been the Mayor of Wexford.) He was in the battle of the Somme after which he contracted pleurisy, which eventually led to his discharge and eventual death. On 12 September 1917 Addison says “I was very sorry indeed to hear about Harry Hadden’s death. He did not seem well the night I saw him (Addison was home in August 1917 prior to Henry’s death) but I had no idea that he was as bad as he must have been”. Evans Hadden (a third cousin) from Tinahely, County Wexford, enlisted in October 1915 at the age of 18. He was in a battalion serving in France, he commanded a Lewis Machine gun section in the trenches, when he was wounded in April 1917 and died after several days on 2 May. He is buried at Aubigny.

Family stories say that Addison was a very good rower and won in regattas across Ireland. He rowed in a four - he and his three friends joined the army, but only Addison returned.

After the War

Of those that signed up from Ireland for the war, 35,000 had died. There was no triumphant welcome home for those that returned. The atmosphere in Ireland was very different to that in the UK where the men were received as heroes. Unfortunately for those returning to Ireland, the political landscape had changed, and the mood was for Independence. For many, those who had fought for the British, were unwelcome. Many of the soldiers that returned were wounded or shell shocked and unable to return to their old lives. 135,000 British ex-servicemen were living in the Republic of Ireland in 1921. Of these 37,500 had a disability of one sort or another. Many who returned from the war were also psychologically scarred by the horrors that they witnessed. Some could return to their old jobs, but others were left in poverty. Others went back to their former lives, as I suspect Addison did, as his immediate family were alive and well. He was able to return to manage the shops. The Haddens were also a well-respected family in Wexford.

In December 1918, Sinn Fein had won a landslide victory and they then formed a breakaway government (Dail Eireann) and declared Irish independence. The Irish war of Independence started in January 1919 which was a guerrilla war between the Irish Republican army (IRA the army of the Irish republic) and the British forces and Royal Irish Constabulary. Some of the first world war veterans served in the national army in the civil war. The violence started slowly but gained in ferocity and extent in September 1919 when the British outlawed the Dail and Sinn Fein. The British government bolstered the RIC with recruits from Britain, the Black and Tans and auxiliaries, who became notorious for ill-discipline and reprisal attacks on civilians. Many Black and Tans were unemployed former British soldiers from the First World War. Their actions swayed the Irish public opinion against the British. In May 1921 Ireland was partitioned and a ceasefire or truce came into being in July 1921. The Irish Free State was formed on 6 December 1922.

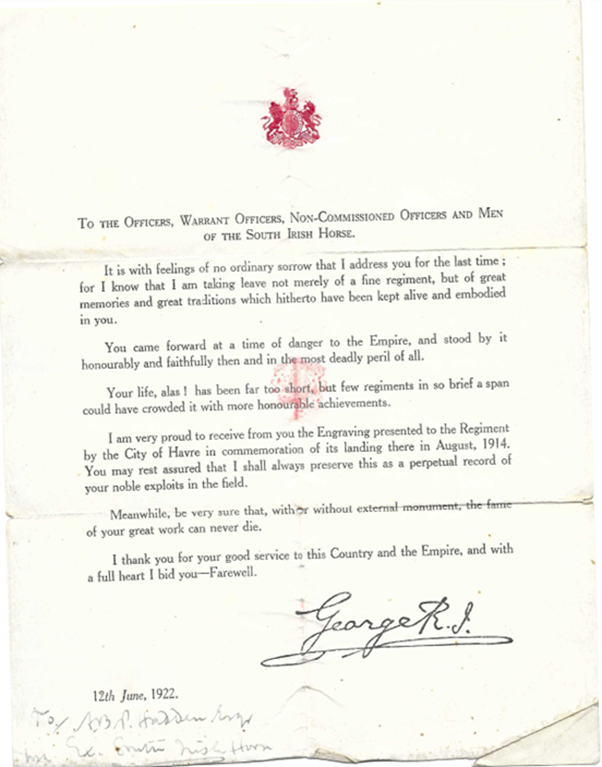

The South Irish Horse was disbanded in 1922. This was announced in February 1922 and was completed by the end of July 1922. On 11 March 1922, the War Office ordered the disbandment of all Southern Irish regiments. This came about as part of the negotiations for the creation of the Irish Free State. On Monday 12 June 1922 the Colours of the five disbanded infantry regiments were handed to King George V at Windsor Castle. The South Irish Horse, having no Colours, presented the King with an engraving given to them by the people of Le Havre in commemoration of their landing at the port in August 1914. The King’s address was sent to all serving members of the regiment and seen below. The SIH had lasted for 20 years.

Above: the letter from King George V sent to all serving members of the South Irish Horse

On the anniversary of Armistice Day on 11 November 1919 at 11 o’clock, there was two minutes of silence, a “calm stillness pervaded the entire city” as people met on St Stephen’s Green. Flags were at half-mast and then “God Save the King” was sung.

However, in the following years this was not the same. By 1920 the War of independence had escalated. Unionist communities treated the day with reverence, but in Nationalistic circles, the recognition was patchy. Commemoration of the day, wearing of poppies continued (although others wore lilies to remember the 1916 Rising) but was not popular with Republicans particularly the British national anthem and waving of Union Jacks. In 1934 an alternative antiwar republican armistice day was suggested which would remember those who fought and died without the frills of Empire. Patrick Byrne, a republican said “I ask you to give the benefit of the doubt to those who wear poppies tomorrow, many will wear them in memory of friends who were deluded into dying for the ideals in a horrible capitalist war. Respect them for the love of their dead people”. In 1939 Eamon de Valera banned wearing of the British Uniform, Union Jacks and singing God save the King and opened Irish National War Memorial Gardens. Once the day moved out of Dublin City centre, most people forgot the event. The poppies also stopped being worn. In July there is a National Day of Commemoration for Irish men and women who have died in war and Armistice Day is remembered in St Patrick’s cathedral.

In 1991 President Mary Robinson chose to attend Remembrance Sunday in St Patrick’s Cathedral laying a poppy wreath on behalf of the nation. The subsequent presidents have done the same. There is a memorial in St Patrick's Cathedral, in memory of the officers and non-commissioned officers and Troopers of South Irish Horse who gave their lives in the 1914 Great War 1918. Erected by their Comrades.

Showing that Ireland has started to change, on 11 November 1998 President Mary McAleese opened the Ireland Peace Park in Messines with an Irish Peace Tower, a memorial site dedicated to the Irish soldiers of all political and religious beliefs who died, were wounded or missing in the war 1914-1918. This was done in the presence of HM Queen Elizabeth II and King Albert II of Belgium.

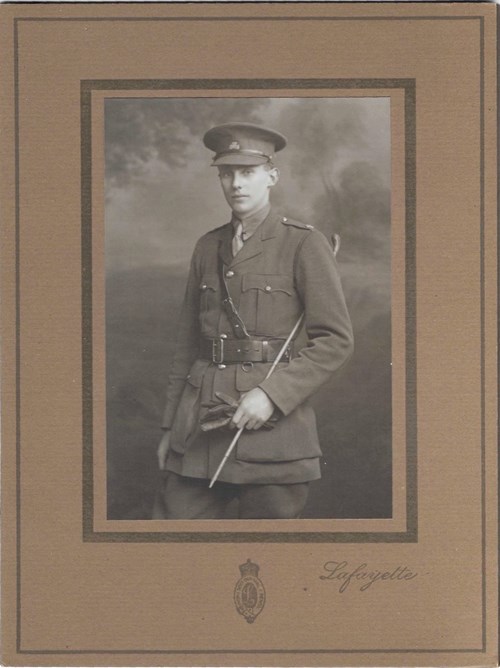

Addison returned to Wexford to work in Hadden’s the Drapers shop again. He subsequently married Frances Newenham and had two children Joyce and Ronald [my father]. He was awarded the “An Caomnoiri Aitiula“ medal.

Above: The “An Caomnoiri Aitiula“ medal

This was for the Re Na Prainne [Emergency Period 1939 -1947] as he was a member of a Local Security Force. He opened his own furniture making factory.

Addison died in 1957 in Wexford.

Article by Victoria Hadden

More about Holzminden Prisoner of War Camp can be read here Holzminden ‘Colditz’ of the First World War?

References

- Tom Tulloch Marshall Military Genealogy and Army Operations. Report for Admiral Sir John Forbes

- South Irish Horse: ciroca.org.uk

- The South Irish Horse in the Great War Mark Perry

- The Missionary Echo of the United Methodist Church. April 1930

- A Coward if I Return. A Hero if I Fall. Stories of Irishmen in World War I. Neil Richardson

- According to their Lights. Stories of Irishmen in the British Army, Easter 1916 Neil Richardson

- British Prisoners of War in First World War Germany. Oliver Wilkinson

- The Missionary Echo of the United Methodist Church April 1930