Albert Perkins - Who Do We Think He Is?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Albert Perkins - Who Do We Think He Is?

Many members of The Western Front Association will no doubt enjoy watching the BBC’s long-running series ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ (WDYTYA) which is now into its 19th series. The research undertaken to unearth the stories of those relatives of the celebrities who served in the Great War is an obvious point of interest for WFA members.

Probably due to research time lag and production delays due to Covid, until now the UK version of this international series (there are versions of the show elsewhere in the world) have not utilized the Pension Records that were saved by The Western Front Association. It was noted that in an episode screened on 26 May 2022, the Pension Records were used to illustrate one of the stories. The use of the WFA’s Pension Records was the starting point to the following article.

Albert Perkins: His service in Salonika

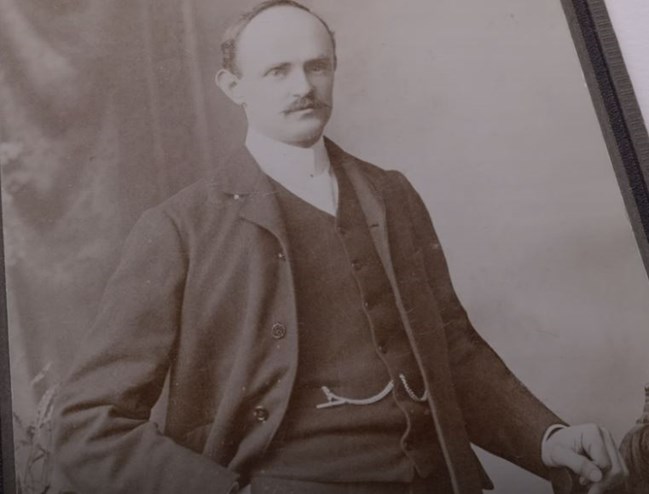

The latest series of WDYTYA recently commenced (May 2022) on BBC1 (it should remain available on iPlayer for some time). In the first episode of the new series we learnt about the ancestors of comedian and TV presenter Sue Perkins. One of the first of Sue's ancestors to be detailed in this programme was Albert Edward Perkins (Sue’s paternal grandfather). Albert served in the First World War and his story was briefly related.

Above: Albert Perkins (a still from the BBC TV documentary)

Clearly, within the confines of an hour-long programme not all the information that could be imparted can be ‘put across’, indeed the clip below is all that was told about Albert’s war service. In this one minute extract, Andy Robertshaw can be seen referring to the winter conditions at Salonka but without being allowed the time to expand the point he was likely to make.

Above: A one minute 'clip' from Episode 1 of Series 19 of 'Who Do You Think You Are?' In this short extract Sue Perkins can be seen learning about her grandfather from Andy Robertshaw. To watch this clip, click the 'play' button in the bottom left corner.

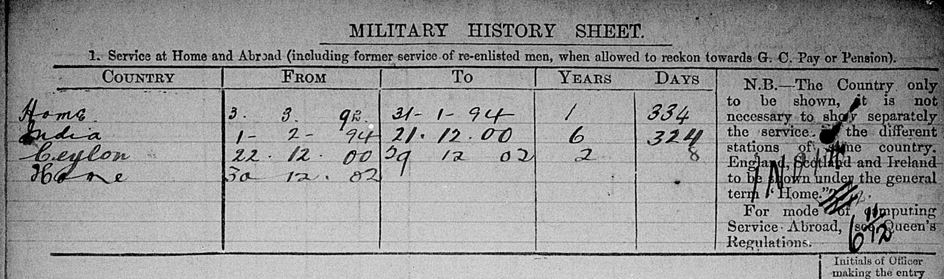

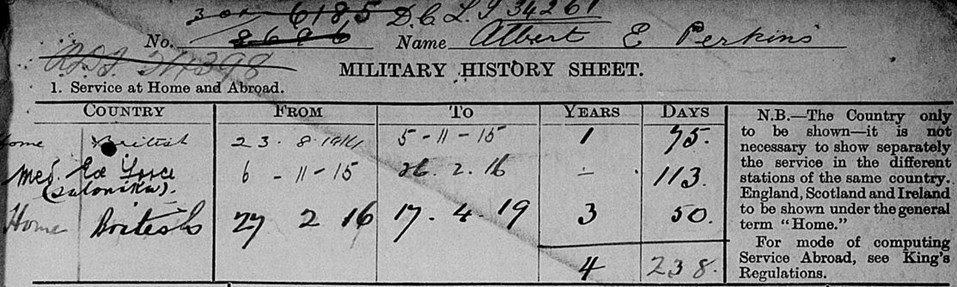

Serving in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry between 1892 and 1904, as can be seen below Albert spent six years in India and another two years in Ceylon.

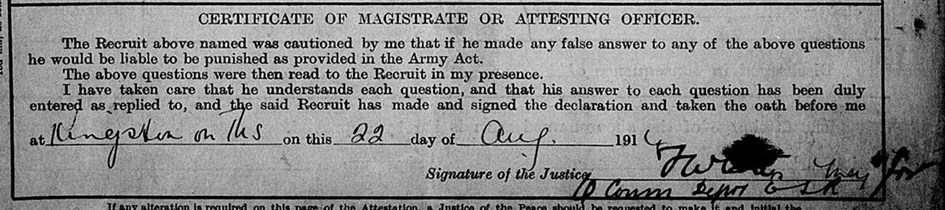

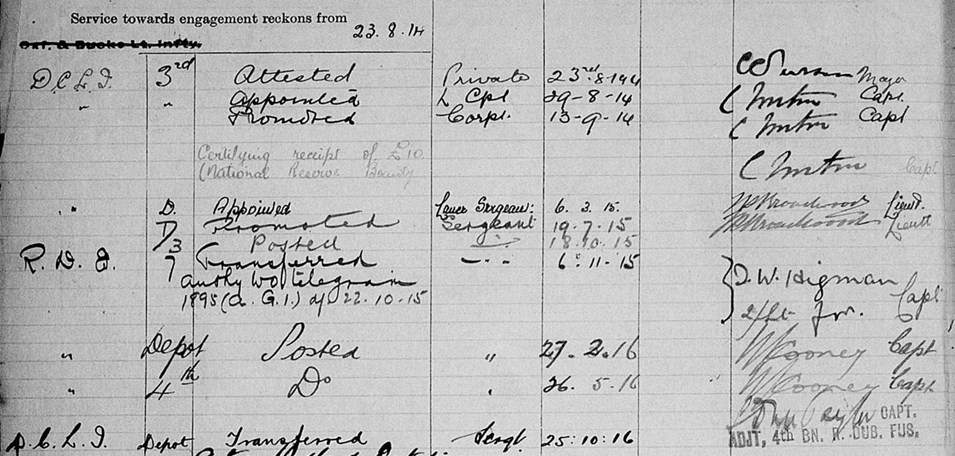

At the outbreak of the First World War Perkins rejoined his regiment (even though at 40 years old there was no need for him to do so). His attestation papers (part of which are shown below) tell us he rejoined the DCLI on 22 August 1914.

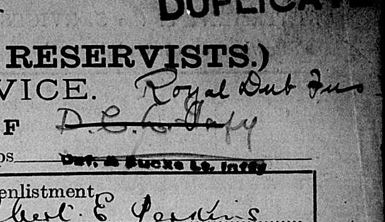

As can be seen below, however, the DCLI was crossed out and 'Royal Dublin Fusiliers' inserted. This factor was not touched on by the BBC progamme.

Promoted to sergeant in July 1915 he was transferred to the 7th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers on 6 November 1915.

The records furthermore show he went out to Salonika where he served for 113 days.

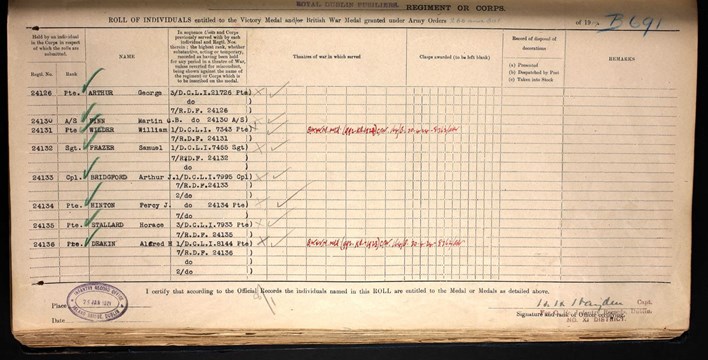

Further research, in particular examining the medal rolls of the DCLI, shows his transfer was part of a large reinforcement of men to the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers (presumably to rebuild the battalion from losses incurred in Gallipoli). On the medal rolls there are multiple pages showing men from this regiment transferred to the 7/RDF. Clearly Albert was part of this process, and as a pre-war regular, and a Sergeant, would have been instrumental in ensuring the reinforcement of the battalion was effective.

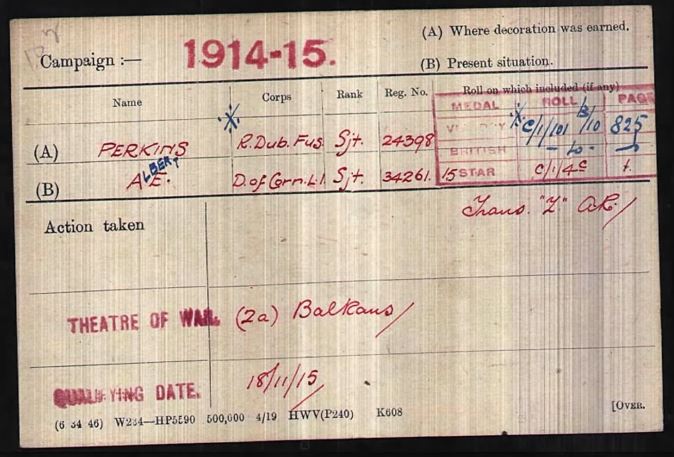

The 10th (Irish) Division at Salonika

After withdrawal from Gallipoli, the 10th (Irish) Division was transferred to Salonika. One of the battalions of this division was the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The War Diary of the 7/RDF is not digitized[1] but it is known that the battalion, together with the 6/RDF went into the line near Lake Doiran on 31 October 1915. Obviously this was before Albert had arrived in the theatre. His ‘qualifying date’ of entry in the Balkans was 18 November 1915.

Above: Albert Perkins' Medal Index Card, note the 'Qualifying Date' of entry into the theatre of operations.

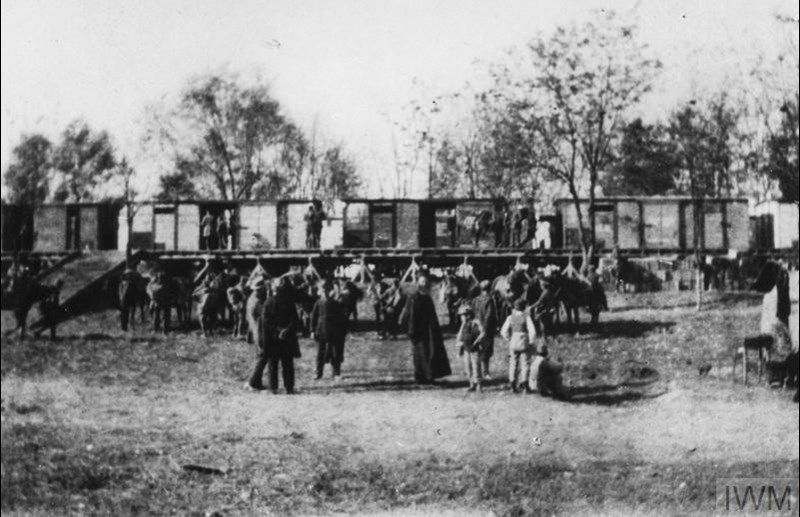

The Division was ordered to advance from the British/French base at Salonika into Serbia – some 70 miles distant. The 30th Bde, of which the two battalions of RDF were a part, went by train from Salonika to Gevgelija and then marched cross country via Bogdanci.

As winter was approaching, and the men were in a hostile environment, any advance by the enemy (the Bulgarians) could be serious. Among the myriad of problems was one of communication, as detailed in the war diary of the 7/RDF:

Communication was established by wire between Battalion HQ and Hasanli, Gockeli-Bala and Brigade HQ and by visual signaling between Battalion HQ and Casuli (now Chaushli). Had sufficient wire been obtainable, communication could have been established by telephone to Casuli, which is the most important of the three villages held.….visual signaling had to be relied upon. This was most unsatisfactory as when the clouds came down all communication with Casuli was at an end except by means of orderlies. [2]

Another officer, Captain Drury of the 6/RDF noted at the end of November

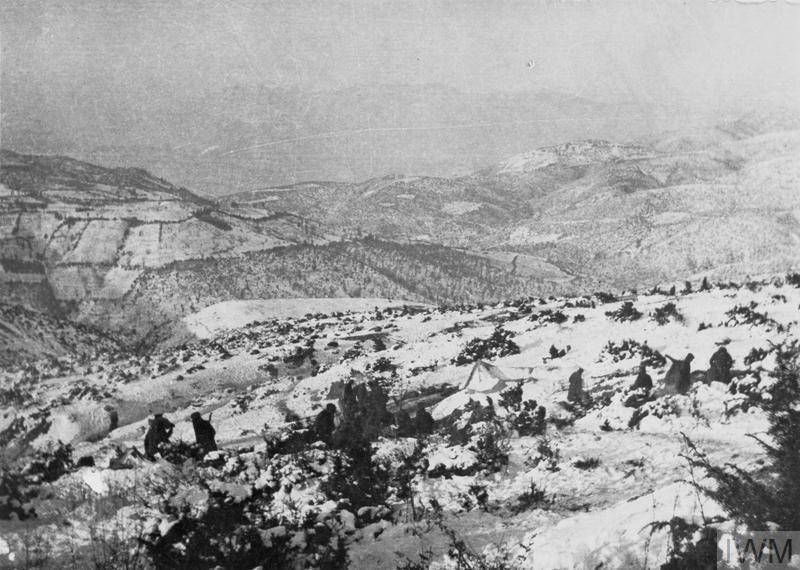

This morning everything is frozen hard and every track is too slippery to walk on….Our overcoats are frozen hard and when some of the men tried to beat theirs to make them pliable to lie down in, they split like matchwood. The men can hardly hold their rifles as their hands freeze on the cold metal.[3]

It is possible that by early December Albert had joined the battalion. Another officer (Captain Nicholson of the 10/Hampshires, part of the 10th (Irish) Division) described conditions:

The weather had developed the habit of snowing hard in the morning, thawing slightly in the afternoon and in the evening a strong cold wind would develop and bring hard frost with it.[4]

Nicholson also described how men of his battalion were attempting to protect their feet from frostbite by coating them in grease and fat from the field kitchen.

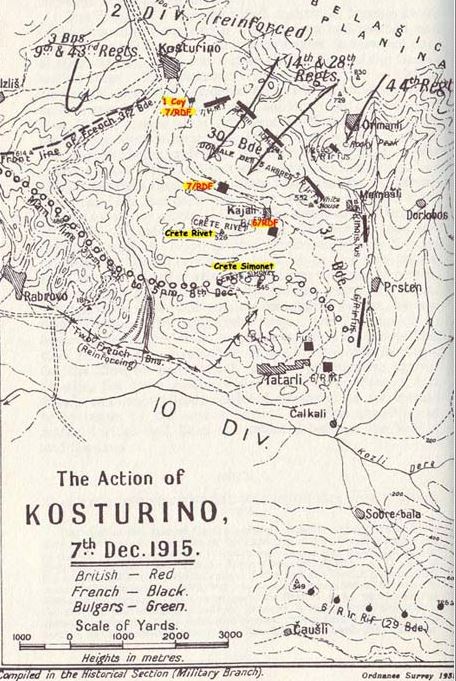

The 7/RDF were at Kajali (the location of this can be seen on the map above) and the war diary describes how a house was taken over in the village where all the sick were brought and where, amongst other remedies, a constant supply of cocoa, Oxo, was kept going.[5]

Above: Bulgarian observation and machine gun post north of Monastir IWM Q 60364

Above: Bulgarian observation and machine gun post north of Monastir IWM Q 60364

On 6 December Bulgarian fire on Kosturino Ridge and the nearby position of Rocky Peak (held by the 5/Royal Irish Fusiliers) increased and was followed at 5pm by probing attacks.

Above: Infantry manning part of the 10th (Irish) Division's line on the Kosturino Ridge, December 1915. (IWM Q 62966)

Above: Alan Wakefield explaining the battle on Rocky Peak

Above: Memeshli is a mile south of Rocky Peak and on the south eastern end of the Kosturino Ridge. The area is remote and sparsely populated. It is now part of North Macedonia but in the Great War was Serbian territory.

The story of the attack on Rocky Peak is told in Alan Wakefield’s book ‘Under the Devil’s Eye’ but also in this video on YouTube > Fighting on the Kostorino Ridge, which tells of the attack on Rocky Peak 7 December 1915.

The survivors of the attack (5/Royal Irish Fusiliers, 10/Hampshires and 5/Connaught Rangers) fell back to a position known as Crete Simonet where they were joined by Albert’s 7/RDF who had defended Kosturino Ridge until about 3.40pm.

The 7/RDF may not have been heavily involved in the action, losing (according to the records of the CWGC) two men on 7 December and another two men on 8 December. (By contrast, the 6/RDF lost nearly 30 men killed at this time.)

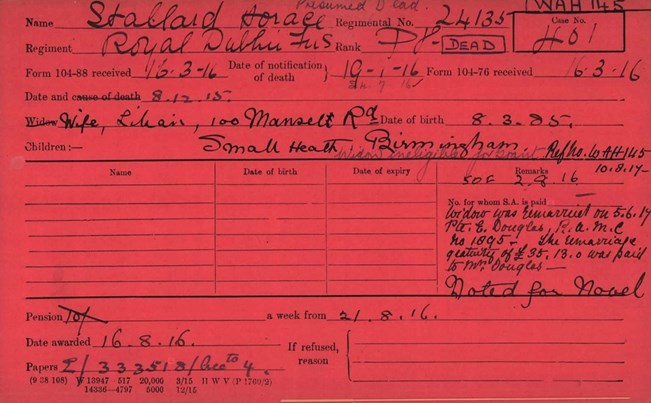

It is notable that one of these men in the 7/RDF who was killed was Private Horace Stallard (number 24135) who was also a transferee from the DCLI. Given the relatively proximity to Albert’s RDF regimental number (24398) it is highly likely Stallard was part of the large batch of men (numbering approximately 200) that were transferred from the DCLI to the RDF in late 1915.

Stallard (whose Pension Records are shown below) has no known grave and is commemorated on the Doiran Memorial.

Below: The Medal Roll (one of many pages of these) showing men of the DCLI being transferred en-masse to the 7/RDF. Stallard is the penultimate entry on this page.

The exact role (if any) of Albert in this fighting is not known. It is without doubt (from records shown below) that Albert was one of hundreds of men who suffered grievously in the winter conditions. Alan Wakefield suggests that nearly 1,700 officers and men were evacuated back to Salonika with frostbite and exposure. From Albert’s service records we know he left the Balkans in February 1916. It is almost certain that this was after some time spent recovering from trench foot. It can be assumed that it was decided Albert was not going to be fit for further action and was sent back to the UK.

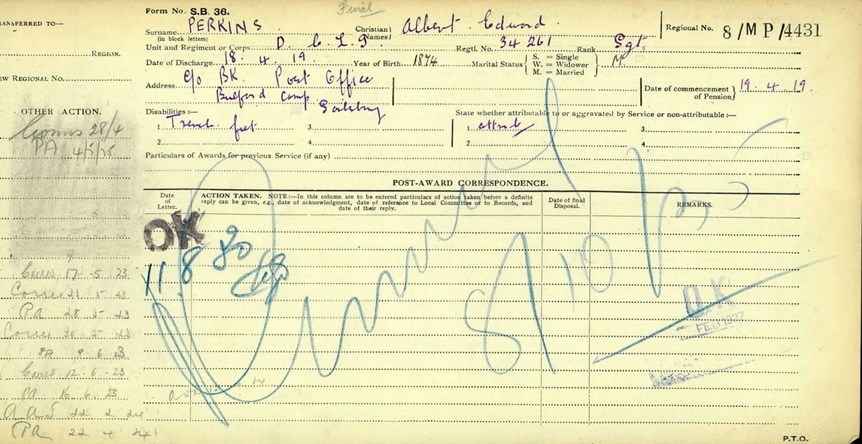

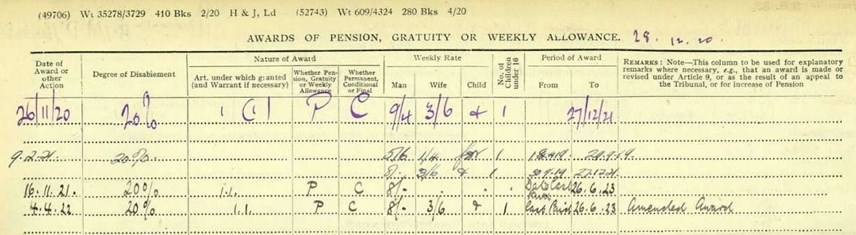

Whilst none of the above was detailed in the episode, the production company did make use of the Pension Ledger – a copy of which was briefly shown by Andy Robertshaw to Sue Perkins to make the point about his suffering from Trench Foot.

Above: The Ledger 8/MP/4431 for Albert Edward Perkins, available via the WFA/s website and Fold3

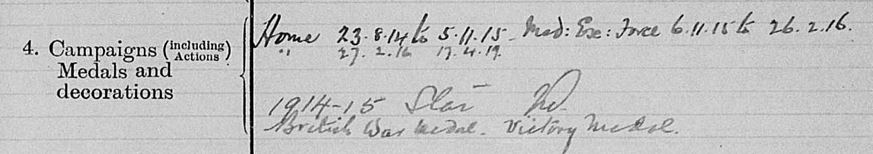

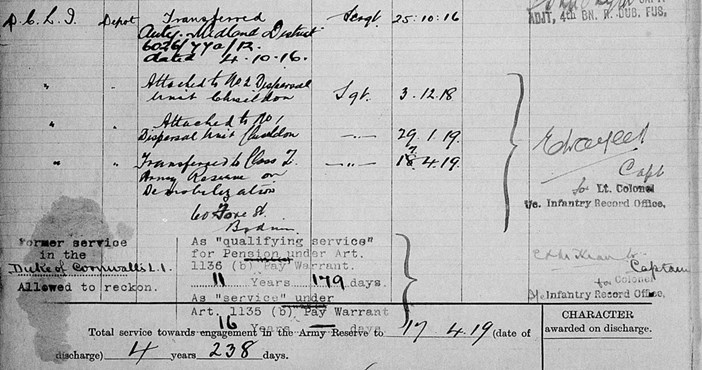

This record shows that Albert was granted a pension for ‘trench foot’ and this was ‘attributable’ to his war service. A pension was awarded (commencing 19 April 1919) which was subject to a number of reviews (as shown on the reverse of the ledger – which did not get revealed to viewers). As can be seen, the pension was granted on the assumption of a 20% disability.

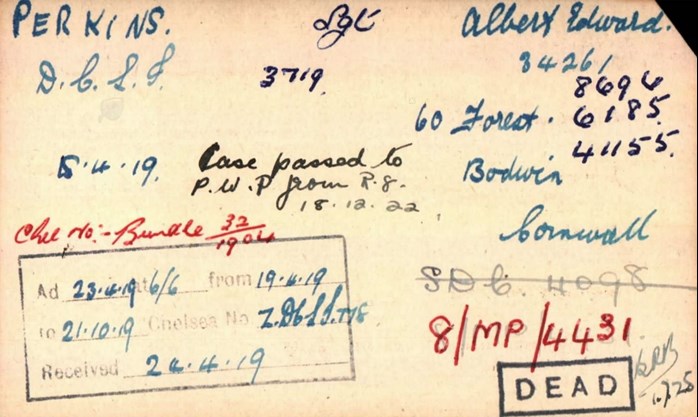

Another record which did not get shown was the Pension Card, which gives the various regimental numbers Albert was allocated together with his address in Bodmin. The address (60 Forest) is almost certainly an error for 60 Fore Street, Bodmin).

Albert's Medal Index Card, which also did not make it into the BBC progamme, has been shown earlier in this article. As members will know, these Medal Index Cards are yet another collection saved for the nation by the WFA.

The cost of the fighting

In the fighting on Kosturino Ridge in the week commencing 6 December 1915, the British Army suffered over 300 fatalities, and no doubt hundreds more men were injured or suffered from disease or the weather conditions. Of these fatalities, approximately 250 were suffered by men - from all corners of the British Isles - who served in the 10th (Irish) Division. A memorial to this division stands on the battlefield.

Above: A group of WFA members in front of the 10th (Irish) Division Memorial. The location of this can be seen here: Divisional Memorials on the Western Front

Very few of the fatalities have known graves and are therefore commemorated on the Doiran Memorial.

Above and Below: The Doiran Memorial to the missing of the British Salonika Force.

Sue Perkins’ grandfather was one of the lucky ones. He came home, and served out the rest of his war in safety in the UK as detailed below.

Albert's wife, Florence Perkins, became one of the UK's first fully trained, official midwives, as detailed in the rest of this episode of WDTYA.

Article by David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

To learn more about the 10th (Irish) Division in this attack, watch the excellent webinar by Alan Wakefield on this subject via the following link:

We Marched Away into Serbia: The 10th (Irish) Division at Kosturino, December 1915

Footnotes:

[1] The National Archives TNA: PRO WO 95/4836

[2] Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011), p.18

[3] Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011), p.19

[4] Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011), p.19

[4] Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011), p.20

Further Reading:

Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody Under the Devils Eye (Pen & Sword, 2011)