An ‘Enthusiastic’ Response to War? British social responses to the outbreak of the First World War.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- An ‘Enthusiastic’ Response to War? British social responses to the outbreak of the First World War.

This is an MA Dissertation submitted to the University of Wolverhampton as part of their 'History of Britain and the First World War. It has been adapted slightly from the original for improved online reading, with links and illustrations added for greater enjoyment.

TITLE: An ‘enthusiastic’ response to War? British social responses to the outbreak of the First World War by Jonathan Vernon

SUBTITLE: 'The Friendly Invasion of Lewes'

Abstract

This study offers a new analysis regarding the meaning and use of the word ‘enthusiasm’ to describe the actions of civilian recruits and civilian witnesses during the early weeks of the First World War. First of all, this analysis is based on scrutiny of the terms ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘mafficking’ and the phrases ‘war enthusiasm’ and ‘no mafficking’ to describe people’s behaviour’ as they appeared in the literature and press. Secondly, it is based on close examination of individual volunteer recruits into Kitchener’s Army from Cardiff and Lancashire into two contrasting regiments, namely the 11th Welsh (Service) Regiment known as the ‘Cardiff Pals’ and the 9th East Lancashire (Service) Regiment. Thirdly, it considers the reaction of the civilian population, based on a case study of the community of Lewes, Sussex, when 10,000 men, including those from the two regiments studied, were billeted on the town. In doing so, this new study goes beyond looking at regional and national recruitment patterns to reveal the individual causes behind the behaviour of recruits and civilians alike at this time.

The historiography led to reading many books, papers and materials published from 1914 to the present day. It is felt that contemporary writers are particularly important at establishing the context and showing how diverse the reasons were for men to enlist. Research of the Regiments required scrutiny of over 1,200 Medal Records to identify the names of the recruits and then to use complete Short Attestation, Service and Demobilisation Papers where extant. These details were cross-referenced with the 1911 Census Records and a search of digitised newspapers. In doing so a profile of over 100 men was built up. The study of what was called ‘The Friendly Invasion of Lewes’ used accounts in digitised local newspapers, a collection of letters from the period discussing events including the billeting of men, an interview in the Imperial War Museum Sound Archive and a collection of photographs taken by E.Reeves of events in Lewes in 1914.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to understand to what degree in the first weeks of the War (August - September 1914) the British population showed enthusiasm for volunteer recruitment. Its focus is on the rush to the colours towards the end of August and early September when recruitment peaked and the transition from civilian to soldier during early training. Memories were stirred of rowdy and jingoistic ‘mafficking’ that had blighted celebrations and anniversaries of the Relief of Mafeking every May since 1900 as crowds of young men gathered, some enthusiastically, some less so, at recruitment centres and depots. This study looks at the nature, scale and intensity of this ‘enthusiasm’.

A study in three parts

There are three parts to this study of the British response to the outbreak of War in 1914

- Part I looks at the historiography of ‘war enthusiasm’ and the use and meaning of the term ‘mafficking’ and ‘enthusiasm’ in relation to recruitment at the outbreak of the war.

- Part II offers an in-depth analysis of the civilian volunteers who enlisted into regiments that made up the 22nd Division, focusing on the motivators for enlistment.

- Part III looks at the civilian response to the war displayed in the Sussex market town of Lewes where 10,000 men of the 22nd Division were temporarily hosted in September 1914.

The study aims to test two contentions in relation to volunteer recruitment in Britain in 1914

The first contention is that there was no ‘war enthusiasm’ shown after the outbreak of war in Britain during the subsequent ‘rush to the colours’. (1)

The second contention is that enthusiasm was ‘merely the conspicuous froth, the surface element only’ when it came to individual reasons for enlisting. (2)

In testing these ideas the study will explore the diverse reasons driving enlistment. Indeed, the evidence shows that there was a wide and changing response to the war and that those who enlisted showed a range of behaviours. These behaviours varied from such extremes as spirited enthusiasm to enlisting regardless of stated antipathy to war. The reasons why men enlisted also varied from the subjective pull of patriotism, duty and peer group pressure, to objective push of dire economic circumstances.

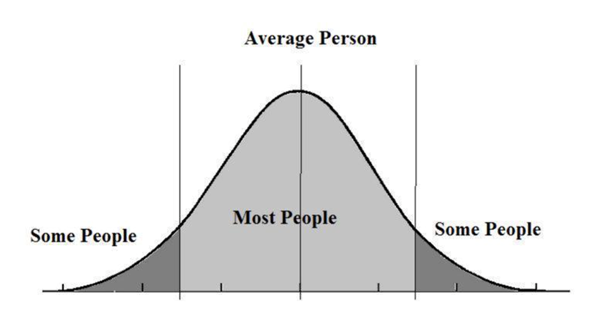

Human Behaviour and the Bell Curve of Normal Distribution

This is a study of human behaviour. It is an examination of the triggers and responses. Human responses, as social scientists show, will occur across a spectrum of reactions commonly illustrated as a bell-curve. This shows that either side of the most common response there are outlier responses too. In the case of responses to the war during its first weeks, this means that whatever the overriding behaviour and response of the majority, there were minority responses that remain valid and reveal social and cultural attitudes towards the war. On the one hand men who enlisted despite an antipathy to war because they felt it was their duty and the cause was just, whilst others responded in a more emotional war, also patriotic, but with distinct overtones of jingoism.

The raising of Kitchener's Army in 1914

The diversity of responses to volunteer enlistment is now accepted and permits this study to develop the idea of a spectrum of responses on a ‘bell curve’ of human responses to recruitment. A bell-curve or normal distribution curve is a probability distribution used by social scientists (Fig. 1.). With a bell-curve comes the recognition that the centre ground accommodates the most common attitudes, while at either end come the extreme responses. (3) In this study, in relation to enlisting as a volunteer in Kitchener’s Army, the so called ‘outliers’ at one end include an array of people with powerful religious convictions who enlisted out of a compelling sense of duty despite being antipathetic towards war, while at the other end there were jingoistic ‘mafficking’ war enthusiasts. It is this view of ‘war enthusiasm’ that is contentious in relation to the existing historiography. Pennell, for example, considers such ‘war enthusiasm’ in relation to volunteer enlistment to have been unlikely. (4)

Was there or was there not a 'rush to the colours' in 1914?

At times, the actions and responses to the war in Britain have been overly simplified. The repetition of certain ideas regarding a ‘rush to the colours’ and ‘enthusiasm’ has resulted in these ideas being taken as a given to the point of cliché. In doing so the complexity, shifting behaviours and the individual response have been forgotten. What is more, whilst those writing in recent years understandably supersede previous authors their voices can diminish the insight and nuance of those who experienced and witnessed the events at the time. In terms of ‘enthusiasm’, the kaleidoscopic variety of responses has been reduced to a short list tempered by the debate over the degree to which enthusiasm was shown or not

The act of enlisting in 1914 was in itself a clear demonstration of a radical change of behaviour for eligible male civilians. This ease of transformation was brought on by events and pressures at the time, not least the overnight reinvention of soldering as an honourable activity. Without this cultural shift regarding the soldier there could have been no voluntary recruitment. It was enthusiasm for becoming a soldier that caught the imagination of so many men during a period when coverage promoting enlistment was widespread and intense. Therein enthusiasm was the desired response to the message that was put out.

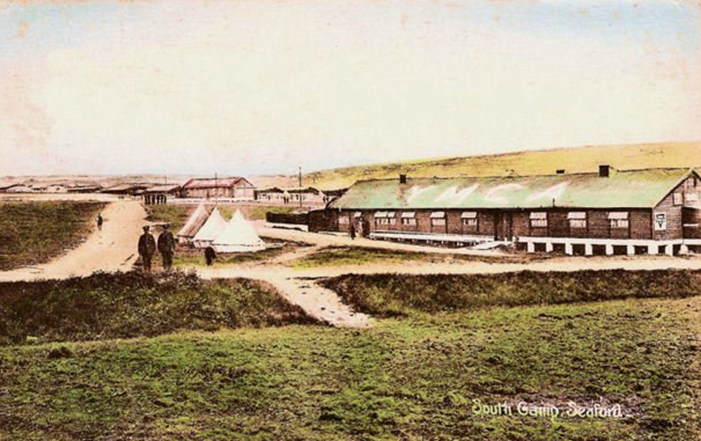

Men recruited into the 22nd Division in 1914

The focus is on men who enlisted into regiments that formed the 22nd Division. This Division was destined for a training camp at Seaford, Sussex. However, problems with the supply of tents, military logistical and manpower issues, and a few days of gales delayed achieving their arrival at Seaford Training Camp until the end of September 1914. (5) Instead, in an effort to fulfil Kitchener’s aspiration to keep many tens of thousands of newly recruited civilians across the Kingdom progressing forward, and away from crowded recruitment centres, barracks and depots, the decision was taken to billet these men for two weeks on the town of Lewes (11 miles north of Seaford). Simply put, unusual circumstances required an unusual response.

This case study aims to bring back the experience of the individual. It looks first of all at the individual recruit coming to a decision in a specific time period and locale. It then looks at the civilian response, typically those not eligible to enlist such as women and older people.

Part I: The Historiography of War Enthusiasm in the early 20th Century

The historiography shows that a bell-curve of human responses is a useful way to address a range of responses to the War from the extremes or ‘outlier’ responses of jingoistic enthusiasm, verging on ‘mafficking’ at one end to antipathy, even opposition to the war at the other. This is a scale that ranges from a negative to a positive view of the war, with the centre ground of pragmatism and duty held by the majority. There is a divide between those who felt they had been compelled to enlist with an extrinsic push driven by lack of support by Poor Laws after redundancy or from lack of work and those who felt an intrinsic pull out of duty and pride for the nation.

In relation to enthusiasm for enlistment there are three groups.

- The first group believes that enthusiasm was nationwide and universal no matter a person’s background or circumstances.

- The second group contains those who say that enthusiasm, if there was indeed any at all, was circumspect and based on pragmatism.

- The third group, which includes some of the original commentators of 1914-1917, offer a more complex and varied picture that is most aptly described as a spectrum where at one end of the scale there was enthusiasm, while at the other there was not.

In 1914, the reasons driving enlistment in Britain at the outbreak of the war were recognised as being complex not simplistic. Emotional and pragmatic reasons, youthful gusto, as well as foolishness and drunkenness all formed part of the mix. Many contemporaries, such as Edgar Wallace, writing in 1915, offer personal observation drawing on reactions at the time which described men enlisting for ‘love’ and for ‘fun’. (6) In contemporary reports you sense that men were caught up in a national movement that carried them along. Similarly, the contemporary reports for The Spectator by journalist David Hankey suggests a range of reasons as to why men enlisted. Hankey says that men enlisted for ‘glory’, for ‘fun’ and for ‘fear of starvation’. Although journalistic and orientated to a middle and upper-middle class readership, as trainee priest and journalist, Hankey had some first-hand experience of working class men having spent time with them as part of his mission. (7) On enlisting he describes men from all walks of life feeling ‘aggressively cheerful’.

There were both pragmatic and subjective reasons for men to enlist in 1914

Two kinds of behaviour are described, on the one hand the subjective on the other the objective. There were clearly pragmatic reasons to enlist, but there were also emotional drivers. This was made easier because opinions about soldiering had gone from a negative to a positive. Events and attitudes together made an overnight change of attitudes towards being a soldier possible. The rapidity of change was itself a reason and excuse for outbursts of zeal. When faced with change and once committed to a response people embrace it with alacrity. In turn, this is how enthusiasm became widespread. Chivvied on by the government and community, many men enlisted and were cheered on by the community as they did so.

As well as Wallace and Hankey, other contemporary authors writing about volunteer enlistment at the time included Captain Basil Williams, C E Montague, Carolyne E Playne, G.V.Germains and Rudyard Kipling. (8) Drawing on first-hand experience and opinion, they put forward a range of reasons for men volunteering. Captain Basil Williams, for example, provides a reasoned list embracing patriotism, ambition, personal courage, love of adventure, want of employment and convenience. (9) By showing that passions as well as pragmatism played a role in the decision making, these observers indicate a variety of shifting responses, into which we must add ‘enthusiasm’ even the loud, jingoistic ‘mafficking’ of war enthusiasm. Such a mix of motivators, as Germain indicates, could include both the objective as well as the subjective as implied by Williams and Hankey. (10)

Wallace, Hankey, Williams, Montague, Playne, Germains and Kipling had first-hand experience of the period of volunteer enlistment and were therefore well able to judge the mood and why people behaved as they did. Wallace wrote numerous fiction and non-fiction books and felt compelled in 1915 to write about the extraordinary phenomenon of the raising of Kitchener’s Army. He describes ‘Kitchener’s Army!’ as ‘a phrase that would stand for all time as a sign and symbol of British determination to rise to a great occasion and to supply the needs of a great emergency’. (11) In this sentence Wallace both indicates that he was a ‘war enthusiast’ promoting defensive patriotism and that such patriotism was a key motivator to enlist. He goes on to suggest that youth blurred the boundaries between the ‘better-class of man’ and ‘more humble’ as all young men were apt to ‘cheer enthusiastically stories of heroism’. (12) We know today that pubescent males, the youth that Wallace and others describe are prone to excitable, risk-taking behaviour. (13) This age profile alone is a good reason to expect an enthusiastic response to events, even more so when egged along by their peer group.

Your Country Needs You

Whilst Wallace’s emphasis is on patriotism, he includes other motivators to enlist such as ‘a sense of duty’, ‘defensive patriotism’, ‘employer compliance’ and ‘employer encouragement’ as well as the provision for dependents and the influence of propaganda such as the ‘Your Country Needs You’ slogan campaign. (14) On this last point Wallace explains how the recruitment message was inescapable, appearing on everything from ‘tram tickets’, to gigantic posters, in leaflets and in people’s windows, as well as being flashed up in ‘picture theatres’, brought up on stage and in the pulpit. (15) It is little wonder that this national recruitment drive, not only given widespread promotion but also supported in the community by worthy and respected notables in patriarchal Edwardian society, could lead at times to what has been described as ‘war fever’. Enthusiasm to enlist was after all the response being elicited. What is more, given the intention to engender enthusiasm we should not be surprised when it occurred with such energy. It is such ‘war fever’ that supports the view that there was ‘war enthusiasm’. In its most literal definition ‘enthusiasm’ should be understood as a quasi-religious fever. In the context of a ‘great’ war, and a nation’s response to it, ‘war enthusiasm’ is the most obvious expression to use. Wallace goes on to explain how there was an about-face of public opinion regarding soldiering, from a negative to a positive, enabling the prospect of enlistment to have a broader base of appeal across the social classes. (16) It is this ‘better class of man’, when they embrace the opportunity, who showed themselves to be particularly enthusiastic.

Mafficking and a cult of jingoistic nationalism 1900-1910

Repeatedly where the phrase ‘war enthusiasm’ is used by the press it is countered with the phrase ‘no mafficking’. Editors wanted to be clear that there was no militarist jingoism attached to the war enthusiasm being proscribed and that such behaviour was unwanted. Their concerns were in part historical and in part in opposition to representations of, and disdain for, Prussian militarism. There had been significant problems in Britain from May 1900 through to May/June 1905 as annual celebrations to mark the anniversary of the Relief of Mafeking turned into an excuse for rowdy, antisocial behaviour. It was such a problem that it led to controls being put on such celebrations. (17) At the time, the phrase ‘no mafficking here’ became commonplace. It was used to describe how there could be public enthusiasm for events relating to Britain, the Empire and the armed services without the militarism associated with the Prussians. When it came to the desperate national drive to recruit a massive volunteer army in 1914, the consequence of this embarrassment in relation to trafficking and Prussianism, was that that open enthusiasm had to be encouraged, indeed necessary if the numbers required were going to come forward voluntarily.

Williams also reflected on reasons why men volunteered and offered a set of factors. These include motivators such as patriotism, ambition, personal courage, love, adventure, want of employment and ‘convenience’. (18) Once again, with a contemporary observer, we see a mix of the passions and pragmatism, and that enthusiasm formed part of the kaleidoscope of responses. Williams shows that men enlisted for a variety of both positive and negative reasons. His use of the word ‘love’ in this context is worth clarifying. It is a synonym for a literal translation of the word ‘enthusiasm’ in its embodiment of passion. We can understand from this that men were moved by their passions and were egged on by society. Many of them enlisted on enthusiasm alone.

Like Williams, Montague also uses the word ‘love’ when describing the actions of volunteers. These ‘Englishmen of faith, love and courage … all as keen as Boys, collectors or spaniels’. (19) In this sentence Montague reveals how and why so many young men had been spurred into action. By ‘collectors’ he uses a metaphor to suggest the obsessive delight in finding a desirable item. While by ‘spaniels’ he invokes the idea of an eagerness to please, even to follow the command of the master. The master in this case is the state represented by the figurehead of Kitchener. The capitalised ‘Boys’ refers collectively to ‘Boy’ Scouts or ‘Boys’ 'Brigades' is a reminder that Edwardian British youth routinely took part in these organisations. Indeed, it has been estimated that 41 per cent of all British male adolescents belonged to such an organisation by 1914. (20) He goes on to put forward a list of reasons why men enlisted, indicating that there were social, economic, political and psychological factors at play. It is this mixed response that suggests that in such a heterogenous group there would be keen enthusiasm at one end of the spectrum, and reluctant compliance at the other, with a myriad of complex and shifting responses in between. To deny that there was enthusiasm is to deny human nature.

Playne describes the mood that came over people as a kind of ‘miasma’ that caught everyone out whatever their station. (21) She has been criticised because of her socialist stance. She paints men as unwitting players in a capitalist game. Yet she is nonetheless animated when it comes to enthusiasm even if she feels the male population had been duped. Once again, she is thus an advocate for enthusiasm as the core motivator and consequence of enlistment.

The nature of recruitment in 1914 evolved

‘The Kitchener Army’ by V W Germains was published in 1930. Two vital points he makes are that the growth in Kitchener’s Army was ‘an evolutionary process’ and a ‘very individual process’. (22) From the perspective of this study, the interest is in the second phase of this evolutionary process, after the first stumbles into volunteer recruitment in August when the seriousness of the situation was realised, when ‘something big was at stake’ and recruitment level hit a peak. (23) He offers many motives to enlist including patriotism, want of employment, ambition, personal ambition, love of adventure and the sheer impulse of going with the crowd’. (24) However, being a witness to events, what is clear is that he felt decision making was subsconscious, that ‘a state of almost hysterical excitement by propaganda from the press and platform’ results in a ‘mighty outburst of patriotism’. (25) He goes on to say how the volunteers showed a ‘fierce enthusiasm, the same spirit of going to war almost as if on a crusade.’ It is this spirit, that of the individual as well as the crowd, that time and hindsight has diminished. Indeed, writing in 1930 he suggests that ‘time has dimmed enthusiasm; sorrow overclouded the glory of that great rising to arms’, a time when ‘men went mad at the strains of 'Tipperary’. (26)

Rudyard Kipling was an enthusiastic recruiter for Kitchener's Army in 1914

Kipling, a prolific author, commentator and speaker wrote a series of articles for the Daily Telegraph at this time. (27) He was an advocate for the Government, notably for the charitable Prince’s Fund that was responsible for recompensing men who enlisted. He was very much in the camp that considered the war a ‘serious’ business and that those like him who could not personally enlist should take it just as seriously. (28) Between Germains and Kipling we have advocates for a subconscious and for a conscious response; the first emotional the second pragmatic. The reality is that amongst the recruits and civilians both behaviours occurred.

Notions of enthusiasm have been overblown and simplified by many historians in the past

Arthur Marwick, Kenneth O Morgan and A J P Taylor considered ‘enthusiasm’ to be a given at the outbreak of the war. (29) Writing typically between the 1940s and 1970s theirs is a perspective that still holds some sway, especially among journalistic interpretations. In 2014, for example, BBC Wales journalist Phil Carradice wrote of the mood of intense patriotism that broke out [in Wales in 1914]… as men flocked in their thousands to enlist … all eager to serve.’ (30) Overblown and simplified, these notions of enthusiasm became the exclusive reason for men’s ‘rallying to the colours’. It was the accepted norm for a period. Marwick exaggerated the nature and scale of enthusiasm, while Morgan, writing a history of Wales, took enthusiastic support for the Great War to be akin to patriotic fervour. (31) Taylor and other historians writing in the 1960s and 1970s also took ‘enthusiasm’ as a given, a comprehensive interest in, and easy access to the vast archive of regional and local newspapers having not yet been established. (32)

Did men enlist alone or as part of group?

Brown, W J Reader and Parker make efforts to distinguish between the behaviour of the group compared to that of the individual. (33) Each begins to identify the variety of reasons why men enlisted. Brown identifies factors such as impulsiveness, patriotism, to escape a dull routine, for travel and excitement, and to join the comrades in arms. (34) Brown describes the ‘heady atmosphere’ in Britain in 1914 as one where ‘amazing acts of personal and communal patriotism became possible’ and of the ‘eagerness of public school boys’. (35) He talks of the way many men enlisted as ‘boyish enthusiasm’, of those who felt their duty as Christians was to enlist. He also points to the context that included bands, patriotic songs, posters, speeches by politicians and women shaming men with a white feather. (36)

War - the ultimate field sport for gentlemen

Reader identifies the context of late Victorian and Edwardian empires, calling war ‘the ultimate field sport for gentlemen and the machinery that satisfied this state of mind’. (37) Reader, with his emphasis on the upper and middle classes, thinks of the volunteer recruitment period as ‘one of the most extraordinary mass movements in history’, with ‘probably the most enthusiastic volunteers the world has ever seen’. (38) He offers his own set of reasons why men enlisted. These include ‘loyalty and attachment to the Throne and Empire’, ‘pay’, recollection of the response to the Boer War, ‘high spirits’ and the ‘romantic glamour of war’. Much of this was conjured up by books of the era, employers facilitating enlistment and the power of the early war poets, with ‘their verse, melodious and full of naive enthusiasm of the day, the great vogue!’ (39) Reader qualifies the view of enthusiasm as a ‘popular movement without jingoism’.

Recruitment in 1914 and the British Public School Ethos

Peter Parker, an English Literature scholar, uses a cultural study based on literature that is either by, or about, these well-heeled men. These men set the trend. In a highly patriarchal society they took the initiative and led. For example, it was a junior solicitor and Army Captain who set up the Cardiff Pals. (40) Though writing about the response of young men from public schools and using literature as his primary source, Parker nonetheless provides some interesting insights. (41) He makes a strong case for the ‘public school ethos’ having a pervasive influence in British society. It was invoked through Boys’ Brigades and the Scouting movement, but also promulgated in a highly patriarchal society by civic leaders and business owners, mayors and their wives and daughters, church leaders and in volunteer groups. He argues that not only was ‘the public school ethos’ projected by the Upper and Upper Middle Class, but that it permeated to the middle and lower classes. It was their ownership and interpretation of a stoical, patriotic defence of hearth and home that transcended the so called ‘mafficking’ of the Boer War years that enabled outpourings of enthusiasm.

So keen they joined the ranks rather than wait for a commission

Reader and Parker show how the public-school educated were for the most part at the ‘enthusiastic’ end of the spectrum of responses exhibited by British civilians. Many of these young, single, men with no dependents to support, were enthusiastic enough to give up university places to join the Army. Some were so fired up that they even joined the ranks rather than seek a commission. Some young men in the lower classes, in an era where people were class conscious and knew their station, revered the behaviour of middle-class men and saw it as a model for their own behaviour.

There were a wide range of responses to recruitment

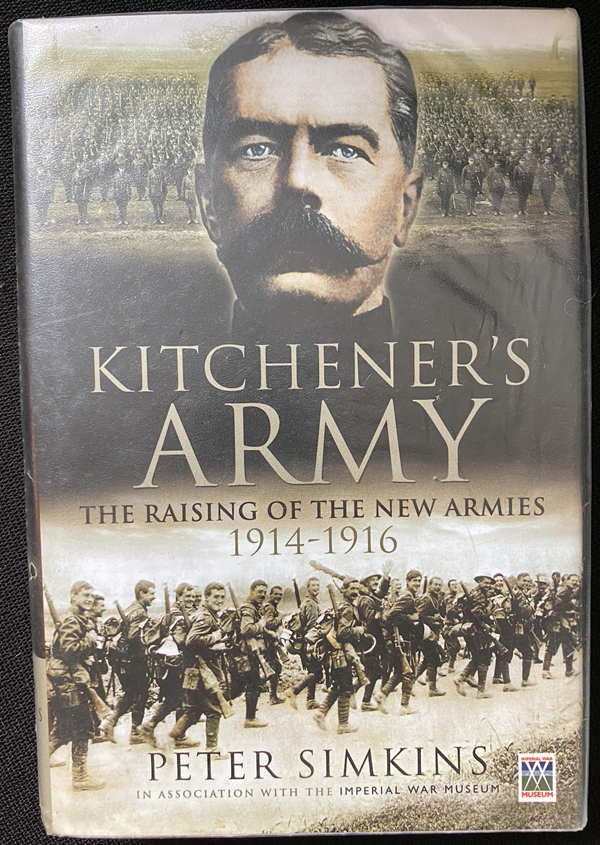

Peter Simkins’ seminal study Kitchener’s Army: The Raising of the New Armies 1914 – 1916 should sit at the centre of any discussion of volunteer enlistment and enthusiasm in Britain during the First World War. (42) As has already been shown in this section, Simkins was not the first person to analyse why men enlisted in 1914. However, he was the first to do so in depth. He scrutinised the IWM records and then compared and contrasted individual stories. In so doing he established that there had been a wide range of responses to the recruitment crisis. It is this wide range of responses that must be kept foremost in mind. We have to look beyond the response of the majority to understand how at opposite ends of a spectrum of responses men behaved quite differently. At one end sat the reticent, informed by a conscience based on religious beliefs. At the other end, were the impulsive, overly enthusiastic and outright jingoistic. While in the middle the majority were making up their minds for a mixture of reasons that included their pragmatic realities and others who were wiped along by the spirit of the moment, a sense of adventure and duty.

There are areas of overlap between Brown, Simkins and Reader. For example, all three identified peer pressure as a prevailing factor. Brown and Simkins recognised ‘escape from a dull job’ as a motive and credited the influence of both formal and informal recruitment initiatives. Reader and Simkins also identified ‘employer pressure’ as a factor, whilst Brown and Reader gave ‘travel and adventure’ as reasons to enlist. Simkins expanded on this list of causes for enlisting and produced nuanced differences, such as an individual ‘taking pride in themselves’ and ‘taking pride in their community’, having ‘a sense of duty’, and a ‘desire to defeat Germany’. Simkins describes that there were people who enlisted ‘in a rush, fearful that the war would be over before they had done their bit’ and in doing so suggests emphatically that they were enthusiastic about what they were doing. (43) He also challenges the ‘image of a tragic lost generation of young men rushing headlong into something that they did not fully comprehend’ and in doing so requires us to consider the many ‘subtle shades and nuances’ that led men to enlist. It is this complexity and variety of response that makes the case that there was both enthusiasm, and every other shade of response that led to enlistment, including men with religious ante-war feelings who enlisted for patriotic reasons. In this respect, these authors show that there was ‘enthusiasm’ and that in relation to enlisting, there was an ever shifting, nuanced and complex response.

Niall Ferguson and Hew Strachan wrote general histories covering the duration of the Great War, including focus on all the major belligerents. Both include sections devoted to enthusiasm and enlistment. (44) Ferguson and Strachan write about enthusiasm by comparing the culture of volunteerism in the United Kingdom and the Dominions with conscription on the continent. Ferguson considers this ‘urge to do something’ that resulted in men enlisting as the overriding psychological motivator. He also puts emphasis on men being willing to die for the cause. Ferguson, for example, includes both a detailed cultural assessment of European literature at the time of the Great War and an economic appraisal of conditions as he aspired to tap into the zeitgeist of the era. Regarding the outbreak of war Ferguson suggests that ‘feelings of anxiety, panic and even millenarian religiosity’ formed part of the mix of psychological responses. If any of this carried over into recruitment then it would be credible for some to be joining up, carried along by the enthusiasm of the moment.(45) He lists the reasons why British men enlisted, categorising his motivators as ‘economic’, ‘impulse’, ‘female pressure’, ‘peer pressure’ and any national and local recruitment drive. (46) Note that Ferguson credits enthusiasm as a factor in recruitment. He develops impulsiveness further by considering spontaneity as a positive outcome of enthusiasm. Men’s behaviour may have appeared mad or foolish, but once they had taken that decision to risk their life for the country their patriotism could take external expression. (47)

There was a pervasive acceptance and a willingness to 'do one's duty/

Strachan is more dismissive of ‘enthusiasm’ as the primary instigator of action to enlist, instead arguing that the ‘highfalutin ideas of a minority are projected on the majority’ and that the common denominator ‘may more accurately be described as passive acceptance, a willingness to do one’s duty’. He goes on to suggest that ‘enthusiasm was the conspicuous froth, the surface element only’. (48) He concedes that some men enlisted with enthusiasm, but that others were reluctant and fearful. Importantly, between them, Ferguson and Strachan support the view that there was a spectrum of responses. What distinguishes Ferguson and Strachan is the scope of their respective works. In their efforts to understand the zeitgeist of the period Ferguson and Strachan are joined by Kit Good whose approach was to probe a narrow range, rather than geographically wide research area. Whilst the perspectives taken by Ferguson and Strachan are a European and a global one respectively, that of Good is a narrow one based on England and his MA dissertation on Mafficking in Harrogate then developed into his PhD thesis. (49)

Good explores the psychological reasons that drove men to enlist. Like others, he proffers the view of a spectrum of feelings ‘that run the full gamut of emotions. (50) Good dismisses ‘the diversity of inspiration and motivation’. He describes ‘war enthusiasm’ as resulting in a behavioural change. Good includes in the argument the community-wide urge ‘to do something’. This resulted in such actions as generous and multiple charitable donations and the ‘pageantry’ of recruitment and soldiering. (51) People participating in such acts contradicts any notion that there was little or no ‘enthusiasm’ because in order to behave in this way people had had to be suitably motivated to do so. Good comes to the conclusion that ‘enthusiasm’ was the ‘inward celebration of community rather than an outward bellicose response to war’. (52)

Adrian Gregory, David Silbey and Catriona Pennell elaborate on the idea of a spectrum of responses and through statistical analysis and close scrutiny of national and local newspapers demonstrate its variety and complexity. Silbey’s focus of study was the working class, mostly British urban males, while Pennell studied discrete populations chosen from selected regions she considered representative of Great Britain and Ireland. The Irish press were the most damning of the ‘Mafficking Spirit’, the inclusion of which in Pennell’s work diminishes the significance of enthusiasm to the point where she dismisses it. The Irish Press reported critically on mafficking in London and across the rest of the UK in 1900 and subsequently with each May 2nd anniversary of the Relief of Mafeking. They also stated clearly that no such behaviour took place in Ireland. (53) It is these repeated statements regarding the lack of ‘mafficking’ and ‘war enthusiasm’ in Ireland which swayed Pennell’s overall view against enthusiasm entirely and led to her non-committal conclusion that there was ‘not necessarily’ any enthusiasm at all. (54)

Gregory, Silbey and Pennell discuss enthusiasm and its relationship to enlistment providing a set of reasons and arguments to explain the behaviour of civilian volunteers. Each qualifies a type of enthusiasm that can be placed on a spectrum and proposes a variety of reasons why a man might enlist. Timing, circumstances and events causes such a spectrum to shift its centre of emphasis more one way than the other.

By aggregating thousands of individual accounts of the volunteer enlistment period 1914-1916 Simkins was able to identify both general and specific reasons why men came forward, including as many as 400 ‘mavericks’, as he calls them, who enlisted multiple times, the ‘blind drunk’, ‘desperate’ and ‘delusional’. (55) These 400, a tiny fraction of those enlisting are what social scientists would call statistical ‘outliers’. If there were outliers who showed ‘war enthusiasm’, then behind them on such a spectrum are those who felt and expressed their ‘enthusiasm’ to a lesser degree. In either case, the charge is made that a considerable proportion of recruits into Kitchener’s army, especially in early September 1914, showed some degree of enthusiasm.

There are people whose individual stories rarely made it into the Press and whose life stories are too often overshadowed by the letters, diaries, memoirs and poetry of the middle, upper-middle and upper classes. It is to these unwritten ‘individual stories’ relating to the working class that attention should be fixed. The work of Silbey, in this respect, is particularly good at seeking to understand the impacts upon the working class at this time, their mood and behaviour. This can be achieved by illustrating the diversity of individuals who were faced with the decision on whether they had to or should enlist and elaborating their circumstances.

Gregory probed widely without limiting himself to Pennell’s selection of discrete geographical areas. (56) He points out that most of the men who enlisted were young and single. He believes that there was ‘excitement’ felt by such enlisting men and moreover that there was ‘enthusiasm’ in particular for ‘defensive patriotism’. (57) Gregory builds on the work of Simkins and digs deeper into the reasons men enlisted, concluding that simplistic generalisations have underplayed the complexity of responses. (58) On the one hand Gregory looks at factors universally accepted as impacting on recruitment, such as ‘a sense of duty’ and ‘fear of defeat’, while on the other hand he develops nuanced positive ‘pull’ reasons to enlist such as ‘pride in oneself’ and ‘pride in the community’ contrasted with negative ‘push’ feelings of ‘shame’, or being seen as a ‘shirker’ or ‘slacker’. (59) Gregory shows that the British public as a whole, not just those who enlisted, felt an ‘urge to do something’. In this respect he alerts us to the need to consider ‘enthusiasm’ as a factor affecting the entire population. Gregory writes that ‘simplistic generalisations about war enthusiasm not only iron out the complexities of society, they also gloss over the complexities of the individual response’. It is this individual response that Good saw as ‘behavioural change’, ‘inspiration’ and ‘motivation’; while any ‘all encompassing explanation’ risks being ‘glib and inadequate’. (60)

Silbey, by focusing on the working class, refreshingly offers a point of view that is much more aligned with the majority of volunteer recruits who were, after all, working class men. Silbey empathises with the individual faced with an extraordinary decision to take and recognises that many recruits were young, sometimes ‘silly’, considered themselves invulnerable and wanted to prove their standing to their family, friends, colleagues and community. (61) Silbey expands on what Simkins calls a ‘sense of duty’ and that men enlisted to ‘defeat Germany’. This was ‘defensive patriotism’ fuelled by ‘fear of invasion’. Like Simkins, Silbey recognises the desire of men to ‘escape’ their circumstances suggesting that it would have been a desire to get away not only from an insecure, lowly paid job with few prospects, but also to get away from overcrowded dwellings too. In this respect, Silbey gives economic factors as a reason to enlist, adding that men who delayed the decision to enlist did so until they had clarification on allowances and understood that their job would be kept open for them.

By acknowledging this diversity of responses we must include the most extreme responses from opposite ends of the ‘bell curve’ spectrum that has been described. At one end of the spectrum there was cold apathy, mixed with a pragmatic recognition to ‘get the job done’, displayed even by pacifists. While at the opposite end of the spectrum, there were ‘war enthusiasts’. When newspapers repeatedly qualified ‘enthusiasm for the war’ with the phrase ‘no mafficking’ it was as a directive to the public not to behave in such as way for the very reason that such behaviour had occurred before, and was considered to be un-British and distasteful and that to ‘to maffick’ was to evoke abhorrent Prussianism. (62)

At times the ‘myth busters’ exaggerate how an event was written about in the past, in particular implying that all writers were for many decades blind to alternatives to the idea of ‘enthusiasm’. It can be seen, as historians have studied and scrutinised the multiple factors that led men to enlist, that ‘enthusiasm’ as the sole or major factor has been watered down and increasingly diminished in importance. Although Pennell goes so far to conclude that ‘war enthusiasm’ was ‘implausible’ as an adequate explanation, she also concedes that factors relating to enlistment were ‘complex’. It is this complexity that allows, rather than denies, the existence of either ‘enthusiasm’ or its more acute manifestation ‘war enthusiasm’.

In the cases of DeGroot, Winter and Terrain, a more nuanced approach to the phenomenon of ‘war enthusiasm’ is offered, while Todman, Sheffield, Bowman and Connelly, support and build on the view of a ‘spectrum’ of feelings and responses, both to the outbreak of war. (64) Once again, it is a spectrum that has enthusiasm at one end and its antithesis ‘apathy’ and outright ‘opposition to war’ at the other.

As pointed out, three camps emerge amongst the historians. There are those who tend towards the left hand side of the ‘bell curve’ scale favouring the pragmatic response and those who tend towards the right hand side of the scale advocating patriotic duty as the key motivator. The third camp, including those writing about events as they occurred in 1914 and soon after offered a variety of reasons why men enlisted. This third camp also includes historians from the 1980s onwards, such as Simkins and Ferguson, who returned to the approach of the first commentators by giving a range of factors rather than simplifying this recruitment period and the motivations of the men down to a sort of movement. Thus, this historiography shows that the reasons why men enlisted and the response by the public was wide ranging. We now turn to these recruits.

Part II: The 22nd Division, Cardiff Pals and 9th East Lancashire Regiments in Lewes in September 1914

This chapter will focus on the 10,000 volunteer recruits of the 22nd Division who found themselves billeted in the Sussex town of Lewes from 14-28 September 1914. These men, with the exception of the officers and most of the NCOs, had enlisted in the first two weeks of September 1914 during the second and biggest ‘rush to the colours’. (65) In depth analysis of this cohort offers insight into the motivators and behaviours driving these individuals to enlist.

The 22nd Division was a part of Kitchener’s Third New Army, established under Army Order XVIII. It consisted of twelve regiments recruited from the western and northern command. (67) For the most part the men of the 22nd Division were from Southern Wales and the North West of England, though men from the North East of England, London and the South West also enlisted into these regiments. (68)

To enable an in depth study that traces the individuals, and the motivators that drove them to enlist, two regiments of the 22nd Division, the 11th Welsh Regiment (Cardiff Pals) and the 9th East Lancashire Regiment (9th ELR), will be analysed. (69) These men represent a twenty per cent sample of the division. Significantly they also provide a contrast between a ‘Pals’ battalion, made up largely of middle and lower-middle class clerical workers from Cardiff, and a battalion of working class labourers from the textile industries and mines of southern and eastern Lancashire. Hence parallels and differences in the motivators behind each group will contribute to class related nuances in the current debates about British responses to the First World War. Each group will be assessed in their respective contexts, drawing information from newspaper reports, letters, diaries, memoirs and post-war interviews. Where their Short Service Attestation (SSA) exists details of age, height, weight, occupation and religious beliefs will also be assessed. (70) Army Service Records (ASR), meanwhile, provide information on the individual’s disciplinary record, promotion and discharge, factors which in turn give an insight into character and behaviour. Demobilisation papers also include pre-enlistment occupation details, in some cases including precise information of a former employer. These records create a picture of who these men were. This in turn enables reasons driving their enlistment to be considered and a detailed image of the individuals to be formed.

Cardiff in 1914

We begin by looking at Cardiff. Cardiff in 1914 was a thriving, international, city with a substantial part of its exporting and importing business centred around the docks and surrounding ‘Canton’ area. Cardiff was considered to be the United Kingdom’s third most important port after London and Liverpool. An indicator of the international nature of the Cardiff population was illustrated in the 7 August 1914 Aliens Registration Act which showed there were people from 23 countries in the city, including Germany, France, Austria, Russia and Portugal as well as Norway, Sweden, Mexico and Japan. (71) South Wales, pre-war, had some of the lowest unemployment rates, which in turn had fuelled influxes of workers.(72) Indeed, in the thirty years prior to 1914 workers had arrived from the south west of England as well as substantial immigration from Ireland, France and Germany. With a diverse population, the response to the war was set to be equally varied. Moreover, not only did the composition of the city embrace national and cultural differences but also multiple religious affiliations. Those enlisting included non-conformist Welsh chapel goers, Roman Catholics, Church of England, Jewish recruits. There was even amongst their number one who described himself as a ‘spiritualist’ and another as having ‘no religion’. (73) It is from such a diverse and cosmopolitan population that the 11WR were recruited. It is also from this heterogeneous group that we would expect a distinct spectrum of responses.

The context for recruitment in Cardiff was influenced by a number of powerful events, embracing local, national and international factors. These in turn influenced how people would behave. For example, the ‘French Colony’ whose young men were called up, were given a rousing send off. It is this kind of response and behaviour, witnessed and reported in the local papers, that suggested to readers how they too should behave once they became the recruit or part of the waving crowd. In relation to the Cardiff Pals there is no evidence that men joined up to escape dull, dead-end jobs. In fact the opposite appears to be the case. Many of the clerical jobs they held were well paid and had career prospects. Moreover, they had opportunities to gain further skills, such as shorthand, typing and bookkeeping, to enable still further advancement. Post-war many of the survivors returned to the same jobs, underscoring that enlistment was not an escape, but rather it marked an interruption from that occupation. (74) Compared to other regiments of the 22nd Division, the Cardiff Pals were economically well off. For example, in a middle class, 4 bedroom home in Cardiff the head of the family might have an annual income of £340 p.a. compared to that of a working class family on £15 p.a. Given that the ‘push’ factors amongst these men were so few we must therefore consider the ‘pull’ factors that persuaded the men to enlist.

By far the greatest number of men enlisting into the Cardiff Pals in early September 1914 were clerical staff. These clerks worked for the council or in a range of shipbrokers and shipping related enterprises, as well as everything from iron and steel, to coal exporters and Gaumont, the film distributors. (75) The shipping industry was severely disrupted during the first weeks of the war but by the time the ‘Pals’ regiment was established the triple-insurance on cargo that had brought shipping to an abrupt halt had been lifted. The added attraction of the Pals was that it gave middle-class white-collar workers a way to enlist that would avoid their having to mix with the labouring men of the working classes. (76) That said, prior to their departure to their designated training camp notices in the local press opened the ranks of the Cardiff Pals to a broader cohort. This in turn brought some miners and general labourers to train and fight alongside journalists, printers, jeweller’s assistants, tailors, teachers, an architecture student and a land surveyor. (77)

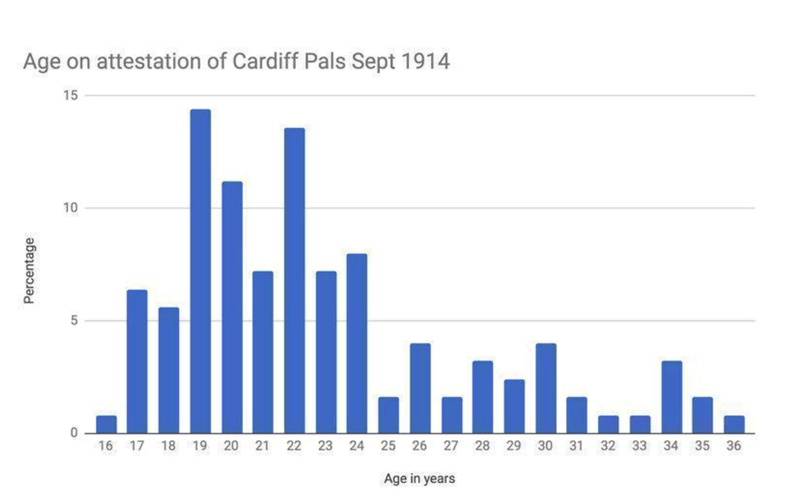

Table 1. Cardiff Pals by age on attestation in the first two weeks of September 1914. (78)

Age and weight show an interesting distribution. The official parameters for the permitted age range was between a minimum age of 19 and maximum age of 30. However, when cross referenced with Census records, it emerges that in practice men as young as 16 and as old as 56 were admitted. (79) Youth, as social studies have shown, is a strong determinant for a variety of impulsive behaviours and risk taking. Boys of 16 or 17 who were psychologically immature, and often physiologically undeveloped, formed part of the recruitment cadre. These boys enlisted for a myriad of reasons including a sense duty, defensive patriotism, to defeat Germany, for economic reasons, peer pressure, employer pressure, emotional blackmail, to please a girl, out of shame and fear, for fun, for moral and religious reasons, to escape dull dangerous, insecure jobs, for adventure and escape, because it was ‘the thing to do’, not to miss out, or because they were drunk or delusional. Key, however, was that they were carried along by the group. Most men, nearly 75%, enlisting into the Cardiff Pals, based on the records available to us, were between the ages of 16 and 24. It is this group behaviour that favours the view of outward displays of enthusiasm.

Most of the Cardiff Pals were single. Most lived at home with their parents, in large families. According to the 1911 Census return, some families also included a live-in relative or lodger. There was a stable family income and ample room to accommodate everyone. This also attests to the sense that these men were attracted to the army rather than driven into it out of economic or domestic desperation.

Cardiff had a diverse population with a range of religions represented. (80) For example, the Fligelstone family, widowed mother, five sons and three live-in servants, lived at 27 Cathedral Road, Cardiff, at the time of the April 1911 Census. (81) Most family members worked for the Roath Furnishing Company. All five sons from this well-off middle-class family enlisted in the Armed Services, two, Bertie and Theo, joining the Cardiff Pals. The brothers are featured in photographs taken soon after enlisting in Cardiff and a little over a month later having arrived in the tented training camp in Seaford in late September 1914. They captioned the later photograph ‘The Jewish Section’ of the Cardiff Pals. (82) The Fligelstones were typical of those enlisting in the Cardiff Pals, as many were well off, educated and in good jobs. To indicate the class composition that made up the 22nd Division, Percy King, age eighteen when he enlisted, was the son of a solicitor and lived in a thirteen-room house that included parents, siblings and a live-in domestic servant. (83) Similarly, 27 year old Samuel Bennet, a coal merchant, whose family home had 10 rooms and at the 1911 Census included the family and a live-in domestic. (84) L/Cpl Joseph Brailli, his father a shipbroker, whose family home in 1911 had 14 rooms, and included in the residents a domestic servant. In contrast to this wealth, we know that five butchers joined the Cardiff Pals in September 1914. Henry Oscar Lewis, aged 20 when he enlisted, lived in a three roomed house with his mother and two brothers. (85) Despite the repeated desire by journalists and commentators to treat the British male population ages 19 to 32 as the same, they clearly were not. Whilst the Army aimed to create conformity, it was forced to do so from diversity. It is this diversity that produced a full range of responses which included both enthusiasm and apathy.

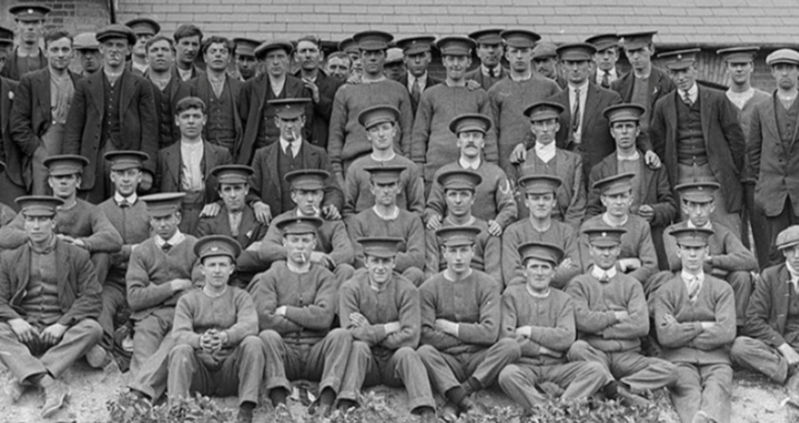

The photographs of the Cardiff Pals undergoing drill, marching down to Cardiff Station on 14 September 1914, in Lewes the following week, and then at the training camp in Seaford all corroborate this great range across the classes. (86) There are men in trilbys alongside those with flat caps, and looking at the detail, men with stiffened collars and ties, alongside men with no collar at all. (87) The Western Mail, meanwhile, includes intriguing detail regarding the efforts by dapper ‘nuts’ to maintain a gentlemanly appearance during their training. (88) Recognising that the men who enlisted in the Cardiff Pals were so diverse supports the view that the reasons why men enlisted were also varied and complex.

Now let us consider, by way of contrast, the men of the 9th East Lancashire Regiment. The majority of these men came from Burnley, Nelson, Colne, and Preston. The economic pressures to enlist amongst men from East Lancashire joining the 9th East Lancashire Regiment were far greater than for the Cardiff Pals. Indeed, the Army Service Records of the men of the 9th ELR reveal that between half and a third of their army pay was surrendered each month to their wife.(89) Those motivated for economic reasons to enlist were relieved to have pay to send home, board and lodgings. They could now help their family, whether as a husband or son, out of dire economic straits. Those from the cotton industry lived hand to mouth, with several mills in the area shut for a number of years, or operating only on a part time basis, before the war. (90) Preston docks brought in wood-pulp, amongst other goods, and acted as a core employer. However, with the outbreak of war, the triple insurance indemnity put on all cargos hit all imports and exports to the effect that within days mills closed and the docks came to a standstill. Piece workers found they had no work at all or only small part-time work. Wage-cuts and underemployment was the common response to a depressed economic market. (92)

It is important to recognise that it was the collective weekly family income that mattered. The wage earners in the house could include both parents, children from the age of 12 doing part time work, as well as cousins or lodgers who contributed to the rent. ‘The Family Wage’, as Gregory points out, helped support the family which often included a baby, a toddler and other youngsters of school age. (93) Rent was always the largest part of the weekly costs, with the remainder spread across clothes, fuel, lighting and cleaning with barely enough money left to cover the cost of a meagre diet. (94) With a cataclysmic impact on total family incomes many out of work men had powerful, pragmatic, reasons to enlist. Indeed, in some cases enlistment appears to have been an act of desperation. Looking at the Short Attestation records many recruits from the area were underweight even based on the Army’s own requirements and by a calculation of the Body Mass Index (BMI) they were malnourished, even severely underweight. (95) Some of these figures indicate that a young man had lied about his age and was most likely pubescent. These boys and half-starved men were accepted into the Army regardless. This, as has been shown, stands in sharp contrast to the circumstances of the men who joined the Cardiff Pals.

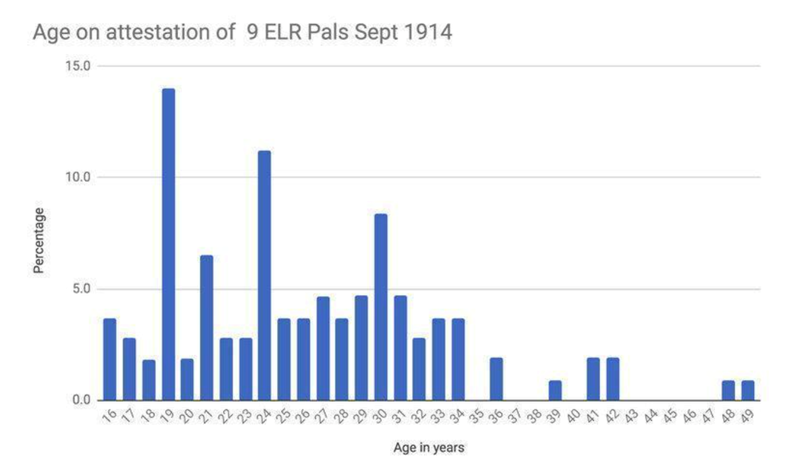

Living vicariously in overcrowded homes, with all income contributing to weekly household bills, many men from Lancashire who enlisted did so because they had no choice. Those who had been paying their textile union subs were told they had to look for poor relief, which was tantamount to a choice between enlistment and starvation. What is telling about the men of the 9 ELR, especially in comparison with the Cardiff Pals, is their age. From the available army records, cross-referenced with the 1911 Census and Medal Roll Cards, we can see that 14% of recruits into the 9 ELR were underage compared to 11% of the Cardiff Pals (see Table 2). We can also determine that 38% of men joining the 9 ELR were married, compared to only 2% of the Cardiff Pals recruits.

Fig. 3. Age on Attestation of recruits joining the 9th ELR in September 1914

The indicators that distinguish the 9th ELR from the Cardiff Pals are the proportion of married working class men with a labouring background either in the textile industry or mining. The records suggest that some men enlisting into the 9th ELR were from families that had been struggling for some years, given their low weight on attestation. Fourteen percent were underweight, below the required 110 lbs required for recruits, though they were nevertheless passed as medically fit. (96) One of the lightest men, Albert Sebastian, an 18 year old who falsely gave his age as 19, weighed only 49 kg (7ft stone 7, or 102 lbs) and was 5ft 6 inches (1.7m) tall. (97) A calculation between their weight and height indicates that many of this cohort of recruits were underweight. Passed as medically fit, it must have been hoped that regular meals and training would build them up, the need for numbers fuelling their acceptance.

There are many individual examples from both the Cardiff Pals and 9th ELR that indicate the contrast between these Regiments and between those who enlisted into them in late August 1914 and early September 1914. For example, the 36 year old John Hartley, who gave his age on attestation as 32, was a miner from Burnley. His wife was a cotton weaver and since at least the 1901 Census her mother lived with them and their four children, one of whom, George, was employed as a weaver aged only twelve. (98)

Joseph Davenport, meanwhile, a labourer in civilian life was living with his parents, his father a platelayer on the railways, and his six siblings all aged between three and twenty, a total of nine persons in four rooms. Joseph too was discharged, in his case on 2 October 1914 as medically unfit. (99) Their poor physical and mental health, the overcrowding and dire economic circumstances suggests that many joined the 9th ELR out of desperation. In an overcrowded home the living-room had to serve for sleeping, cooking, eating, washing and laundering, even for childbirth and dying. (100) More men from the 9th ELR had been living in what was termed ‘overcrowding’. In 1911 over 30% of the British population was living under conditions of more than three person per two rooms. Given circumstances such as these it is understandable that many men joined the army in August and September 1914 in order to escape their circumstances.

Growing up in the Salford Slums, Robert Roberts, who was born in 1905 and had first hand experience of growing up in this kind of environment describes the working class as a complicated mix. Tradesmen and artisans, and semi-skilled workers in regular employment made up the top tier. (101) Unskilled workers were split into plainly defined groups and grades of casual workers of all kinds with dockers and street sellers having the least prestige because of the uncertainty of the employment chances. (102) From such a complicated mix we see a complicated response.

The spectrum of responses considered in relation to enlistment are the product of a single, common act - that of enlistment. As men entered into this contract, however great their youthful bravado, they must have understood that they were giving up their old existence in exchange for one that risked their being killed or maimed. The collective responses varied between those of the majority that sat either side of pragmatism and opportunistic adventure and the minority outlier responses at either extreme where there was commitment despite having negative religious views regarding war and outright gung-ho enthusiasm. The spectrum of responses to the circumstances of early experiences of soldiering ceased to be based on common experiences during unusual periods such as being billeted. As the experience of 10,000 men billeted on Lewes shows, whilst some recruits were guests of the wealthiest residents of the town and were treated like the prodigal son, at the opposite extreme others slept on the floor of an incommodious and insanitary old workhouse, got little sleep and were poorly fed. Faced with this varied experience it is not surprising that the response to the war could vary considerably. Though the harshest words were to describe the experience of camping out in the workhouse as ‘no picnic’, for others, as guests of Lewes, it was both a picnic and a joy. Once again, from initial responses to the experience of being a recruit, circumstances could vary greatly thus making individual experience and response either a negative or a positive one.

Part III: The ‘Friendly’ Invasion of Lewes in September 1914

The two week sojourn of 10,000 recently enlisted civilian men in Lewes was dubbed ‘The Friendly Invasion of Lewes’ by the local Sussex press. This study of the events in relation to the behaviour and mood of the recruits and the civilian population will interweave the experience of the recruits and their hosts. It will begin with a look at Lewes as the context into which the recruits would be sent. This will be followed by the recruits leaving depots for Lewes to put up in the most extreme range of accommodation. The third part looks at how the men were kept occupied and controlled by the Army and received and entertained by their hosts. The fourth part shows how the billeted men experienced mixed fortunes based on where and with whom they were billeted. There were winners and losers amongst civilians and the recruits. In consequence there was disappointment, grumbling and complaint about circumstances at one end of the scale, while at the other end of the scale the generosity of hosts and the atmosphere generated by garden parties, the crowded music hall and at an celebratory ‘international football’ match were openly enthusiastic.

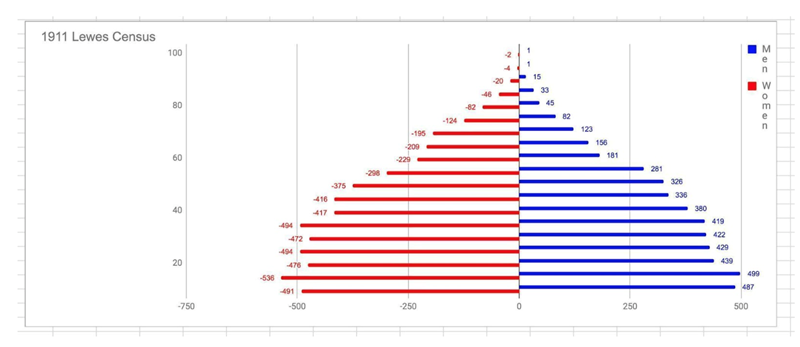

It is important to understand what Lewes had to offer in 1914. For most recruits this was an unfamiliar world. It was strange because of the town’s comparative wealth, partially agrarian background and its modest size when compared to the large, urban industrial, mining, iron working and textile manufacturing towns the recruits had come from. How the population of Lewes lived in 1914 ranged from overcrowded, often dark and damp Victorian back to backs and two up two down houses. The 1911 Census shows that at times 5 or 6 or more ‘persons’ lived in a 3 room dwelling, to the large, detached houses of ‘The Wallands’, the ‘high-class’ part of town. (103) Here a house with 7 rooms might have 5 occupants, one or two of whom could be live-in domestic servants. It was into these homes, largely of the middle and upper-middle classes that half the men were billeted for a two week stay.

In 1911 Lewes, Sussex had a population of 9,653. (104) Though a modestly sized town, it was nonetheless home to the County and Assize Courts, Lewes Prison and sizeable County and Town Council buildings. The census demographics show that the population was young. In 1911 one-third of the British population were children under fifteen with as few as 5% over the age of 65. (105)There was a predominance of infants and children. The average family size was 4.35 people. (106) Whilst the overall average occupancy rates for Lewes was low compared to other towns in Sussex, such as Newhaven and Brighton, there were wards in Lewes, such as Westgate Street and St Pancras, where higher occupation rates were the norm. (107) In the least well-off homes there were no sinks, no drains and a communal W.C. These homes were damp, unventilated, dilapidated, unsanitary and overcrowded. (108) The houses built alongside and over the Winterbourne in St.Pancras were prone to flooding. It is into this market town, of mixed fortunes, wealthy investors and businesses owners at one end, self-employed unskilled labourers at the others, that the 10,000 recruits of the 22nd Division were sent. Given such circumstances the fortunes of the recruits would be mixed. As would be the experience of the population, many of whom would not benefit from having the men in the town while suffering the inconvenience of their presence as grocers, bakers and butchers ran out of provisions.

Fig. 4 Population Pyramid for Lewes, based on April 1911 Census of England & Wales

Whilst everybody in the town was expected to take recruits in, including the well-do families of ‘The Wallands’, there were dwellings where this was impossible. An already overcrowded home, populated beyond its capacity, simply could not accommodate any recruits. There were financial benefits to having men billeted that the most needy households could not take advantage of.

Edwardian Britain in the early 20th century was paternalistic and stratified

The class divisions were distinct. (109) In Lewes the class divide in 1914 was approximately 75% working class, 20% middle class, 4% Upper Middle Class and 1% Upper Class. (110) There were many differentiators between the classes, the obvious one being annual incomes. The income of a middle-class family was about £340 annually as compared with £75 for an industrial worker. (111) However, the divisions went further. As Silbey established, the working class, by far the greater part of the population, saw themselves as forming further distinct subgroups. (112) These included the skilled and unskilled workers, the self-employed, and the unemployed. The influx of men brought challenges but also opportunities. When faced with a demand to take men in, it was reported that some refused until they were told they would be paid.

The housing stock in Lewes in the early 20th century was highly diverse

The upper-middle class business owners, barristers and a few ‘upper class’ ‘landed gentry’ and owners of stock lived in the large detached houses in ‘The Wallands’. It is from here that we have the personal accounts of the 20 year old Miss Iris Mary Hotblack in the form of letters to and from male and female friends. Living at ‘The Boltons’ with her parents and two brothers, Mary had been privately educated at an independent boarding school. The family had two live-in domestic servants at the time of the 1911 census. (113) The Mayor and his wife lived in this part of the town too, as did other business owners and their families. These well-to-do middle-class homes were lit with electricity, had bathrooms and many had a telephone and gramophone. (114) Recruits billeted here, often officers, were treated to their own beds, the sheets changed daily, meat at breakfast and in the evening, and even entertainments put on by one of the households on the avenue. In the well-off parts of the town, people could afford to enter into the hosting of their guests with generosity. In other parts of town, accommodated as lodgers, the recruits were given no special treatment. One landlady saw this as a chance to make some money and did so in a way that meant the soldiers complained about the paltry meals. (115)

On 7 September Rudyard Kipling spoke at the Brighton Dome strongly in favour of enlistment by all able men. The report of his speech is repeatedly punctuated by ‘cheers’ indicating how well such speeches such as these were received and how easy it was to galvanise the enthusiasm of the crowd.

“It will be a long and a hard road, beset with difficulties and discouragements; but we tread it together, and we will tread it together to the end.” (116)

It is in this spirit that Lewes took on the challenge of housing 10,000 men for a fortnight.

The first men to arrive in Lewes went into public buildings, albeit sleeping on straw strewn across the floors of the County Courts. Some satisfied their hunger on the way to billets by pulling up carrots from gardens or taking apples from trees. (117) We only have two first hand reports, one from a recorded memoir, the other from a journalist for the Western Mail writing for his newspaper. While still in civilian clothes they had to learn to subsume their individual differences. ‘Being novel and interesting we do not grumble, as yet’, one wrote. He was in the County Hall and reported that he had ‘tried to sleep while some kept up incessant conversation through the night’. They would have to get used to roughing it, and for many in Lewes it was a rude awakening. An unnamed journalist went on to write that they had slept in their clothes’ and that, on an early morning stroll, he had noticed that many doors had chalk marks on them. ‘This may be our good fortune’, he added ‘if there are enough houses to go around’. (118)

Tired and hungry, the mood of the poorly accommodated men would be tested. Even more so when a substantial theft of meat diminished the daily ration. (119) In such a situation any enthusiasm was quickly dampened by the daily realities. As one report attested in a note in the Western Mail to say how the Cardiff Pals were faring, it was ‘not a picnic’. (120) We were ‘like tramps sleeping in a hayrick’ another man reported to The Western Mail. The Cardiff Pals fared worse than others. For the most part they were billeted in public buildings, not just the County Courts and Council Buildings, but also the Old Workhouse. Closed for three years, efforts had been made to overhaul the plumbing of the Old Workhouse the week before. These proved inadequate. As in other public buildings the men slept on straw and were fed centrally. (121) For men of another regiment billeted close to the race course, though also on straw their situation could not have been more different. These twenty men were put up in a ‘gentleman’s racing stable’ - which proved to be cosy and dry, with a breakfast so good it was reported in the paper. On top of a hearty breakfast the men received a large pouch of tobacco each for the day. The owner must have felt some pride in his efforts as E.Reeves photographers were commissioned at some expense to take pictures of the men. ‘Twenty of us were put together in a gentleman’s racing stables. Each of us had a bed. The blankets were good and clean and we slept between sheets waking at 8 for breakfast. A grand slap up feed of big sausages, a finned haddock, and as much jam and bread as we could eat. Breakfast over, a man came in and gave us a parcel of plug (1lb), 1lb tin of mixture, and a box of ‘tabs’. All the houses here belong to gentlemen and we are all made to feel at home.’ (122)

Here we can feel that the home owners could afford to indulge their guests and did so. Enthusiasm in this respect was an indulgence that only the well-off could afford.

Lewes, by September 1914, as across Britain and the Empire, had experienced a month of events that conditioned how the town would react to the arrival of the recruits. At the end of July 1914, Lewes saw men of the Special Service Section of the Lewes Company of the Sussex Royal Garrison Artillery mobilised and departed for Dover. A few days later, on 3 August, members of the Royal Naval Reserve were mobilised, followed by the Lewes Company of the 5th (Territorial) Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment. Over the following month approximately 240 men enlisted up to 4 September. (123) Across the country, peak enlistment occurred at the end of August into early September. This build up was not so much an explosion of ‘enthusiasm’, but rather a multitude of factors picking away at a man’s consciousness. This included, as elsewhere, press coverage, peer pressure and female pressure, economic pressure, recruiting posters, pamphlets, the response of civic leaders and of religious leaders, the attitudes of employers and trades unions, as well as recruitment techniques. (124)

Though not a garrison town, Lewes had close associations with the Sussex South Rifles and Royal Artillery Regiments with whom many men had served in the South African War and to whom many Lewes men still looked for a career. Only a generation before, men had been waved off at Lewes Station to the South African War with marching bands and waving flags. (125) Some local newspapers, such as the Sussex Express, ran stories in 1914 from 50 and 100 years ago showing the county response to the Crimean War and to Waterloo. The implication was that war, though a rare event, could return to challenge a new generation. IN 1914, this was a challenge that the leadership of Lewes was willing to embrace. It was their enthusiasm to support, and to be seen to support the war effort, that led to 10,000 men being billeted on the town. The names of those who shared their commitment appeared regularly in published rolls of honour of those who had given to the Prince’s Fund. (126) These precursory events preconditioned expected behaviours into the population. Crowds learnt to wave and cheer when they saw mobilised soldiers off at the station, especially when accompanied by a band.

Of the approximate 2,770 men of combat age in Lewes, some 400 were mobilised as Regulars, Reserves and Territorials, while some 200 enlisted in August 1914 and during the first two weeks of September. Women played a key role in persuading men to enlist. On 30 August 1914, Iris Hotblack, wrote to one of her close male pals, Alan ‘Balmy’ Moreton, a lieutenant serving with the Royal Artillery, detailing how she had convinced two men to enlist. She added that all her ‘men friends have either gone or have enlisted’ and that she felt it was her duty to encourage them. She wrote to him in October 1914 to say how she had found the ‘White feather business’ distasteful. (127) This is indicative of how people could be caught up in the moment. Events around them led to a change of behaviour. In the case of Irish Hotblack it shows how one person’s enthusiasm for the national drive to recruit eligible men led her to take part in a practice that she later found distasteful.

It was at the beginning of September that Iris would have witnessed or been aware of the 100 recently recruited Lewes men gathering in the centre of town ready to be posted for training. The men were addressed by the Mayor, Councillor T. G. Roberts, then marched down to Lewes Railway Station. They were headed by a Boy Scout bearing the Union Jack and the Lewes Town Band, which played on the platform as the train pulled out. Here is an example of where an outward expression of patriotism was organised and managed. This was the kind of orderly enthusiasm for the war directed from the top that was necessary to develop momentum behind the recruitment drive. This contrasts with the disorderly ‘mafficking’ of the decade 1900 to 1910.

It was in this context that the Mayor of Lewes, Councillor T. G. Roberts learnt that Sussex had been selected to take two Divisions of Kitchener’s New Army, and that at County level the choices of Patcham on the northern edge of Brighton and Seaford, along the coast from Newhaven towards Eastbourne, both on the edge of the Sussex Downs, had been selected to take massive camps of men. (128) These were greenfield sites, chosen for their suitability and availability to take between 20,000 and 30,000 recruits each Other towns regionally that already had men billeted on them included Haywards Heath, East Grinstead and Uckfield, though none in the number expected at Lewes.

Having committed the town to a considerable challenge the town’s Mayor, the town’s leaders and notables set out to meet this challenge, managing potential problems while playing the host. As the press were right to comment, the town may have taken on too much and the town’s means and people overstretched. It is when and where ‘overstretched’ that the good humoured mood could turn sour.

In an unusual period of transition recruits still in civilian clothes, half of them put up in private homes, the rest on the floor of public buildings, began their military training and a demanding routine of physical fitness. We uncover the extreme contrast in circumstances the men found themselves in and identify the range of experiences they had. We also look at the response and find that at worst there was some grumbling and the occasional appearance in front of the magistrates for petty theft, while many felt they were treated like the returning Prodigal son.

Lewes residents were warned of the need to billet men on Thursday 10 September and told to expect the first arrivals on Sunday. It was left to Chief Constable Major Lang and his men to allocate billets. The split was roughly 50 % going into public and private buildings and 50% into private accommodation. The town’s municipal buildings, warehouses and malt houses were commandeered, including the old Naval prison and the Council Chambers of the County Hall, the ante-chambers and in the Assize Court. So too were the old Workhouse and The Corn Exchange, the Assembly Rooms and Eastgate Baptist School Room. Taking a patriarchal tone, a stance more accepted in a society that ‘looked to its betters for leadership’, the local newspaper the Sussex Agricultural Express wrote that ‘if all will do their duty in the towns and villages of Sussex, assistance of inestimable value may be rendered to our country’s cause’ and in this spirit of duty and ‘having something the could do’. (129)

Forewarned of the pending arrival of the 10,000 recruits the Chief Constable for East Sussex sent out men door to door to make enquiries and allocate men accordingly. (130) A chalk mark by the front door denoted how many each property would take. The response was mixed: enthusiastic and welcoming from some, antagonistic and difficult from others. (131) It is this mixed response that should be taken as indicative of the mixed and shifting feelings towards events as they developed in these early weeks of the war. It is also this mixed response that reflects the same complex response that we have seen amongst the recruits. The local newspaper reported grumbling, people refusing to take any men, and then, if they had to, only wanting officers. As it turned out, a house was expected to receive the recruits on an ad hoc basis. For example, one woman who had requested being allocated two officers was instead presented with four enlisted men. She initially refused, reversing her position when informed that a fee was payable for each man for accommodation and food. Indeed, she then agreed to take the four and requested another two be allocated to her. (132) People had to be encouraged, told to put men in their sitting room, to use the cellars, attics, dining rooms and billiard rooms. They were challenged with “would you prefer to have Germans taking over the house?” After all, “the men you are entertaining are in training to assist in preventing the towns of England from sharing the same fate as has befallen Liege, Namur and Louvain”. (133) There was a degree of compulsion. 'People who made it convenient to be out did not escape the chalk'. (134) The numbers of recruits billeted at different houses varied from 2 to 25. (135) Care, in terms of bedding, opportunities to wash and breakfast and an evening meal was entirely down to the means and generosity of the host.