An Original First World War RAF Hangar and the story of 'RFC Bramham Moor'

- Home

- World War I Articles

- An Original First World War RAF Hangar and the story of 'RFC Bramham Moor'

Anyone driving along the A64 dual carriageway between York and Leeds may have noticed at a significant barn-like structure set back in the fields from the road on the York side of Bramham junction. The building that is just visible from the road was an original World War One aircraft hangar and 33 Squadron was the first squadron to be based at the new RFC Bramham Moor aerodrome.

Above: the hangar in the distance, this being a 'blown up' image from the nearby A64 main road

Work began on the site in winter 1915. At least nine canvas Bessoneau hangars and some temporary accommodation was set up close to the road that later became the A64, while more permanent structures were constructed on the other side of the field.

Above: Temporary Bessoneau hangars, similar to those built on site when Bramham Moor was being built.

The airfield, hosting 46 Reserve Squadron, came under 8th Wing Headquarters, based at York. Despite its proximity to Tadcaster, it would be known as RFC Bramham Moor until 1 April 1918, when it became RAF Tadcaster. There were no concrete runways: the planes simply used a field which was recalled as being “...rather bumpy, as no attempt had been made to level it." Indeed, learning to avoid such natural hazards was essential. There were a lot of telegraph wires at the end of the runway area, and many pilots caught these on take-off or landing. It was only after several serious accidents had occurred that the wires were finally put underground.

By 29 March 1916 33 Squadron had moved north from Bristol. As a Home Defence squadron, equipped with BE2c’s and BE12s, 33 Squadron’s main task was to protect Leeds and Sheffield from aerial attack by Zeppelins, and it set up its HQ in Tadcaster and based ’A’ Flight on the Knavesmire in York, 'B' Flight and ‘C’ Flight at Bramham Moor - though not for long. A Zeppelin raid on York saw the airfield closed down and ‘A’ Flight moved temporarily to Bramham Moor.

A reorganization of the defence of Great Britain was issued in May 1916, with 33 Squadron picking up the additional responsibility of defending the Humber, and by 24 June 1916 33 Squadron had flights based at Beverley, Coal Aston and Bramham Moor.

There was another change of air defence policy in July 1916, which triggered the move out of Yorkshire and into Lincolnshire. By early October 1916 33 Squadron had established its HQ in Gainsborough, ‘A’ Flight moved to Brattlesby (Scampton), ‘B’ Flight to Kirton-in-Lindsey and ‘C’ Flight to Elsham (Elsham Wold). 57 Squadron was formed from a nucleus of 33 Squadron at Copmanthorpe in June 1916 and took over 33’s part-time training role to allow it to concentrate on Home Defence.

57 Squadron based ‘B’ and ‘C’ Flights at Bramham Moor, and were joined by HQ Flight and ‘A’ Flight in August 1916. 57 Squadron deployed to France in October 1916.

46 Reserve Squadron, with eighteen aircraft of various types, arrived at Bramham Moor on 17 December 1916, moving to Catterick in July 1917. In early 1917 46 Reserve Squadron was joined by 14 Reserve Squadron from Catterick. On 31 May 1917 all Reserve Squadrons were retitled Training Squadrons, as the RFC made a concerted effort to train the pilots and observers instead of providing them the opportunity to prove whether they could, or couldn’t fly.

On 15 July 1918 the aerodrome was expanded to encompass 200 acres, and 14 Training Squadron and 68 Training Squadrons merged to become No. 38 Training Depot Station, equipped with thirty six SE5A and Avro 504 aircraft. These were used for the initial training of the fighter pilots who formed the 38th Training Defence Squadron (TDS).

Above: Impression of the remaining hangar from WW1. It is the only former 1916 RFC hangar that remains at Bramham Moor on what would have been one of the largest aerodromes in Britain, home to a Training Depot Station

Above: Close up to the Hangar

Above Inside the hangar

The late Charles Newham was posted to the station on 4 July 1918, and he related several incidents which took place. There was an old Maurice Farnham and some DH6 aircraft, as well as a few Sopwith Pups and Camels for advanced training. He found that the six or so flying instructors had been sent away to learn about a new aircraft. During this time, flying practice almost stopped and all the pupils could do was to attend a dull lecture or two! However, they did fire off thousands of rounds at the gunnery range at the east end of the airfield. The number of rounds was governed only by the number of magazines a man had the energy to load. At this time, every tenth round had to be incendiary or tracer, which often went high above the ten-foot earth bank....but no-one worried about damage to life or property.

By the end of July, the men's training had really begun. The new type Avro was used initially but more advanced work was done on the SE5A, the standard single-seat fighter on the Western Front. Flying accidents occurred daily, some of them fatal. But with the Officers' Mess being staffed by young ladies, there were other types of accident, Charles Newham recalled: "I remember one occasion, whilst at the Mess. There was a loud scream from the kitchen quarters, followed by a resounding crash of pottery. It was later learned that a young lady had entered a bathroom which adjoined the kitchen for a jug of water WHILST ONE OF THE OFFICERS WAS HAVING A BATH! She then turned and fled, dropping the jug. It was some time before she dared enter the Mess at the same time as the officer."

July 1918 also saw the arrival of a group of American pilots and ground staff. When America had first entered the war in 1917, pilots had gone straight to France where their lack of training (and superior German planes) had caused heavy losses. It had then been decided that all American pilots should pass through a British aerial training school, hence the arrivals at Bramham Moor, now known as RAF Tadcaster. At about the same time the influenza epidemic hit the squadron and almost a third of the men were confined to bed. The others were turned into temporary doctors to help the sick. However, by the end of September several men had qualified, so they were given their wings and posted overseas as fighter pilots.

74 Training Squadron arrived from Netheravon on 15 July 1918 and had disbanded, its aircraft given over to 36 Training Squadron in Scotland. On 17 January 1919, 94 Squadron was reduced to a cadre in and arrived at Tadcaster on 3 February to be disbanded on 30 June 1919. The Ripon-based 76 (Home Defence) Squadron arrived in May 1919 as a cadre and were also disbanded in June. 33 Squadron suffered a similar fate; taking its Avro 504K (NF) aircraft to Harpeswell on 2 June 1919, it was disbanded on 13 June, the same day as 76 Squadron. The disbandment of so many RAF squadrons in 1919 signalled the closure of the airfield. Despite 38 TDS becoming 38 Training Station in August 1919 the unit was disbanded in December 1919 and the Station was closed.

Today, only one of the permanent hangars remains, together with a few out-buildings and the specially constructed road from the A64, appropriately known to all as 'The Hangar Road’. The buildings and surrounding fields are now known as Headley Hall Farm, forming part of an agricultural station belonging to Leeds University.

The hangar, used for grain storage, has a Grade Two listing due to its Belfast Truss roof structure, the name derived from the support used for the arched roof. The roof supporting structure is comprised of a lattice of diagonally interlaced pieces of thin pine. These are held in place by the use of trestle type structures spaced along the external walls of the building, all of which can be seen in the following photograph.

Above: Laminated timber wall posts with external buttresses of the same construction, horizontal ties to these passing through the wall at mid-level and raked ties likewise passing through to the roof trusses, continuous small-paned glazing between these ties; full-height sliding doors at both ends (altered, and replaced or faced with corrugated iron sheeting), with vertical windows and central ventilator in the segmental gable.

Above: laminated timber roof trusses of segmental latticed girder construction

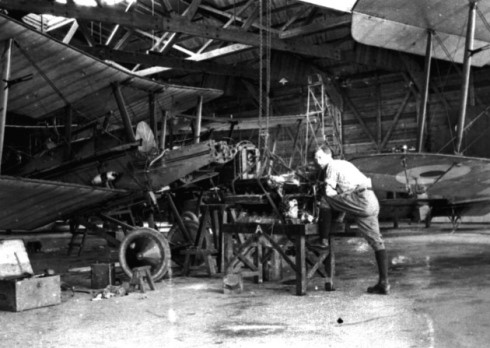

Above: An RFC ground mechanic working on the engine of an SE5a, unfortunately this photograph was not taken inside the hangar at Bramham Moor.

Cyril Ernest Butchers

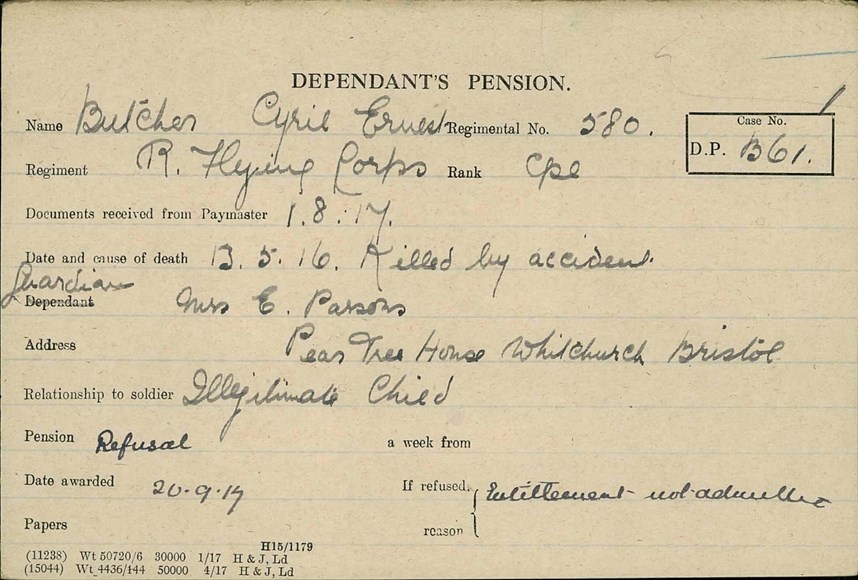

It seems that the very first man that 33 Squadron lost was a young corporal from Bristol called Cyril Butchers. Cyril died on 13 May 1916 and was buried at Fulford Cemetery in York.

In 1911 Cyril Ernest Butchers was living in Bristol with his elder brother and his family, and worked for a while as a clerk and a roller skating instructor at the Central Skating Rink on James Street in Bath.

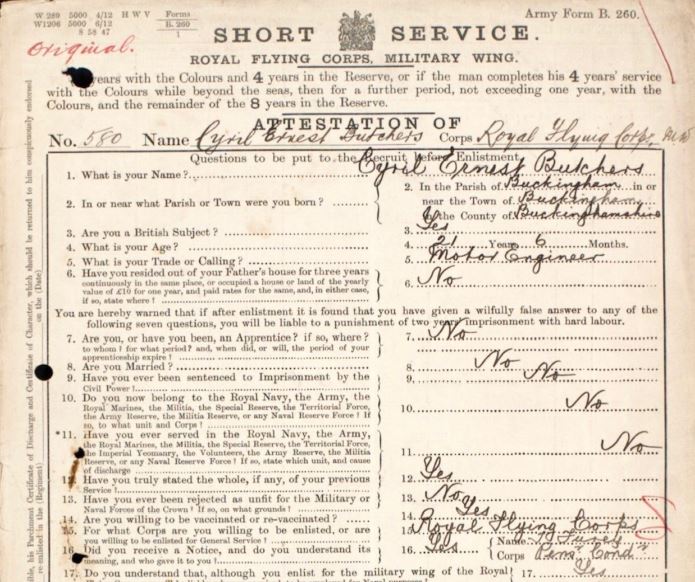

At some point Cyril appears to have taken on a trade that would be better suited to the fledgling Royal Flying Corps; on his attestation papers, signed in London on 4 February 1913, he gave his trade as ‘Motor Engineer’.

Above: His attestation paper.

Below: Cyril Butcher

The following day Cyril reported to the Royal Flying Corps Military Wing at Farnborough. In a newspaper report published in the Bath and Wiltshire Chronicle on 16 May 1916, just three days after Cyril’s fatal accident, readers were told that Cyril had served in France ‘with the Army’ but had been invalided home, and had been at Filton before he moved north.

Cyril could have been in the Tadcaster area for about six weeks before his motorcycle accident happened on 13 May 1916. There had been time enough for the young airmen on their motorcycles dashing up to York for a night out to annoy the locals by riding too fast around the district, a point made at the inquest.

Cyril was laid to rest in Fulford Cemetery to the south of York, and it might have been at this point that Cyril’s real age was scrutinised. In 1911 the census was taken in Britain on 2 April and Cyril’s age was 17. On 4 February 1913, his Attestation papers recorded his age as 21 years and six months. He died three years later, in May 1916, yet his headstone shows his age as 21.

Whatever his real age, Cyril Ernest Butchers was the first man that 33 Squadron lost after its formation four months previous

Above: His Pension Record Card

FLYING CORPS CORPORAL KILLED NEAR WETHERBY

Corporal Cyril Butchers, of the Flying Corps, was killed while riding with companions on Saturday night on a motorcycle from York, in the direction of Tadcaster. The cycle collided with a horse and vehicle at Catterton Lane End, and Butchers was flung on the road and sustained serious injury. One of his companions was also injured. The occupants of the vehicle were thrown out, and the horse was killed. Butchers was removed to the Voluntary Aid Detachment temporary Hospital at Tadcaster, where he died shortly after admission.

AIRMAN’S FATAL MOTORCYCLE RIDE

At Tadcaster yesterday an inquest was held on Cyril Butchers (24) a native of Bristol, and a corporal in the Royal Flying Corps, who lost his life in a road accident at Catterton Lane End, near Tadcaster, on Saturday night.

The evidence showed that Mr. and Mrs. Rhodes, of Catterton, were driving home from Tadcaster in a low “tub,” drawn by a pony. They had a candle lamp in front , and an oil lamp behind, both of which were burning, and they were driving close to their own side of the road. Just before they reached Catterton Lane End they saw the cyclist approaching some 200 yards away at a fast pace. He was evidently in the middle of the roads, and appeared to keep a straight course until a few yards away from the pony, when he suddenly swerved and collided with the trap. He was thrown off his machine, and received fatal injuries.

Major Jubert, officer commanding the 33rd squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, expressed the opinion that when riding at night, and meeting a cart with only one light, one was not certain whether it was a cart or a bicycle. One expected a bicycle to give way. He imagined that Butchers had not realised that it was a vehicle he was meeting until he was almost on top of it, and the sudden application of brakes caused the cycle to skid.

The jury agreed that death was due to an accident, and expressed the opinion that members of the Flying Corps cycled too rapidly through the district.

Tony Whitehead, The 33 Squadron RAF Association Newsletter

Issue 9 Autumn 2018