Arthur Boyle Private and Pensioner

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Arthur Boyle Private and Pensioner

Painting by Diane Lavery 1998 from a photograph of Arthur Boyle taken in 1917

Arthur Boyle, born in 1894, from Castlemaine in Co. Kerry, volunteered to serve in the South Irish Horse on 25 January 1917. He was one of over 200,000 Irish men who volunteered to serve in the British army in the First World War. The great majority came from what is now the Irish Republic.

Arthur Boyle had some experience with horses and, at the time he volunteered, it was thought that there was still a need for forces of cavalry to exploit the breakthrough of the German front line that the infantry were expected to make.

However, Arthur Boyle’s time on horseback was brought to an end fairly quickly.

On 13 July 1917 orders were received that horses were about to be withdrawn and that the South Irish Horse would be dismounted and form an infantry Battalion which became the 7th (Service) Battalion (South Irish Horse), Royal Irish Regiment, on 1 September 1917.

Infantry training took place throughout September and until 22 October 1917 when the Battalion went into the front line. The first casualties occurred on 29 October.

Arthur Boyle was in trenches in the St Quentin sector, close to the strongly defended German Hindenburg Line. The Germans shelled the Irish positions frequently and casualties increased.

Private Boyle almost certainly became a victim of German shellfire. His wounds were so serious that he could have had little or, perhaps, no recall of what had happened, and, since his Service Record was destroyed in the London Blitz of 1940, no one can be absolutely sure of where and when it happened. But Arthur Boyle survived and was honourably discharged from the army on 4 February 1918 at the age of 23.

Arthur Boyle never fully recovered from his injuries. His heart had been damaged and he endured years of poor health. He died in 1943.

What happened to Private Arthur Boyle? Where might he have been when he was wounded? When was he wounded?

I located a transcript of the War Diary of the South Irish Horse from when it became the 7th (RIH) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment, 49th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division and from the time the Battalion entered the front line system of trenches on 22 October 1917.

Men receiving wounds are mentioned in entries for:

29.10.17 ‘Three men of ours wounded in enemy’s retaliatory shellfire’

20.11.17 ‘... 4 OR sustained shell wounds’

30.11.17 ‘... 1 OR slightly wounded’

10.12.17 ‘... 2 of our men were wounded’ (CATELET COPSE)

12.12.17 ‘Billets shelled & 28 men killed & 40 wounded. Capt. Vernon & 1 OR wounded during relief’

(ST EMILIE)

16.12.17 ‘... 1 man wounded’

26.12.17 ‘One man wounded by a stray bullet’ (TOMBOIS FARM)

This represents a steady drain of casualties in a relatively ‘quiet’ area of the front.

Private Boyle’s wounds were serious: a fractured skull and blast/crush injuries. These were not likely to have been caused by a bullet or bullets. It seems to me highly unlikely that he would have survived if he had suffered them out in a front line trench. He would certainly not have been one of the ‘walking wounded’ and able to make his way back for first aid.

Two entries can be ruled out, I think: that of 30.11.17 (victim only ‘slightly wounded’) and that of 26.12.17. (victim ‘wounded by a stray bullet’). Bullet wounds to the head were usually lethal, causing more than a fractured skull. Also this would not account for the damage to Private Boyle’s heart (see his pension Record Form S.B.36 below). It seems most likely that Private Boyle’s wounds were caused by shellfire.

There is no mention of shellfire in the entry for 10.12.17.

This leaves the entries for:

29.10.17

However, the War Diary entry seems to suggest that the men wounded were in the Inniskilling Fusiliers.

20.11.17

There is a possibility that Private Boyle might have been one of the 4 Other Ranks who ‘sustained shell wounds’ on 20.11.17. At this time he would not have been in the front line trench and many of his comrades would have been in the vicinity, engaged, as he was, in digging a communication trench. Rescue and speedy evacuation, therefore, might have been possible.

12.12.17

There is a possibility that Private Boyle was one of the victims of the single German shell which exploded on the billets in St Emilie on 12.12.17. Stretcher bearers and medical assistance would have been immediately available and Private Boyle would have received prompt treatment at an Advanced Dressing Station and quickly evacuated to a safe area. From then he would have passed through a Casualty Clearing Station and an appropriate Field Hospital and fairly quickly back to a hospital in the UK.

16.12.17

Private Boyle could have been the sole casualty in one of the working parties mentioned in this entry.

However, there is an earlier entry in the War Diary for the 1st SIH ‘A’ & ‘B’ Squadron (before they were merged with 2nd SIH to form an infantry Regiment):

15.6.17 to 1.7.17 ‘Drouvin. Working parties employed building strong points in front of British line. Casualties 7 OR killed & 28 OR wounded.’

It is likely that these casualties were caused by shellfire

It is possible that Private Arthur Boyle, if newly arrived from initial training, might have been one of the wounded mentioned above. Again, numbers of his comrades would have been in the vicinity engaged in digging. Rescue and speedy removal for treatment might have been possible.

Footnote to this section

1918 – the destruction of 7th (SIH) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment

From December onwards the British sensed that the Germans might be preparing a major offensive. The very effective German counter-attack in the Battle of Cambrai and their capture of some British positions indicated that Haig’s optimism that the German army was a spent force was clearly misplaced. In fact, the German army opposite the British was getting stronger. German reinforcements were arriving on the Western front having been withdrawn from the Eastern Front in response to an impending peace treaty between the Germans and the Russians. Indeed, the decision to launch an offensive against the British and French had been made as early as 11 November 1917 by the German General Staff.

In accordance with the British defensive plan drawn up by Lieutenant General Congreve of VII Corps, five Battalions of the 16th (Irish) Division, including the 7th (SIH) Royal Irish, were to be kept in the front line. The OC of the Division, Major General Hull, objected but was overridden by General Gough, OC Fifth Army. It was a mistake. When the attack came on 21 March 1918 the Irish suffered many casualties from the German bombardment concentrated on the front line area and the Germans quickly broke through. By the end of that day 7th (SIH) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment, was down to 1 officer and 40 men, the remainder having been killed, wounded or captured.

By then, of course, Private Arthur Boyle had long been out of it.

7th (SIH) Royal Irish War Diary – 21.03.18:

4.30am. The enemy opened a heavy bombardment mostly with gas shells lasting about 4 hours. The morning was very foggy.

8.30am. The enemy attacked and broke through A&C Coys and reached RONSOY VILLAGE before S&B Coys were aware that the attack had commenced. No one of A&B Coys got back to the rest of the Battn, either being killed or taken prisoners. The enemy had practically surrounded the village before HQ and S&B Coys were aware of it, as he had broken through the Division on the right. At this time all the Officers, with the exception of Capt Bridge had become casualties, also the majority of other ranks. The remainder were ordered to withdraw and fought their way back to ST EMILIE where they arrived about 7pm. The strength then was 1 Officer and about 40 Other Ranks which included 5608 Sergt Maloney and 7683 Corpl Harrison. About 9pm. the Battn was relieved by a Battn of the 39th Division, and moved back to VILLERS FAUCON.

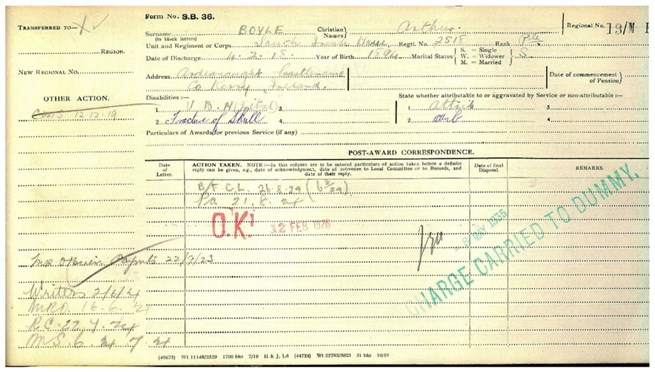

Private Arthur Boyle – Pension Record

Arthur Boyle was able to obtain a pension after his discharge from the Army. The forms from the Pension Ledger were obtained by his grandson from The Western Front Association which now holds the pension records of the soldiers of the First World War.

The clarity of the images of the forms has suffered somewhat in the process of being converted to jpeg format. However, much can still be seen well enough.

Near the top of FORM S.B. 36 we see the entry for Disabilities. The first entry is initially mysterious: apparently ‘V to H (Initral)’. On careful examination (with much magnification!) this is more likely to be ‘V to H (Mitral)’: ie ‘Valve to Heart (Mitral). I think this is medical shorthand for a problem relating to damage to the mitral valve which can be caused by blunt trauma to the chest and which would be heard clearly through a doctor’s stethoscope. The trauma to the chest would probably have occurred at the same time as Private Boyle’s serious head wound – recorded in the second entry as ‘Fracture of Skull’.

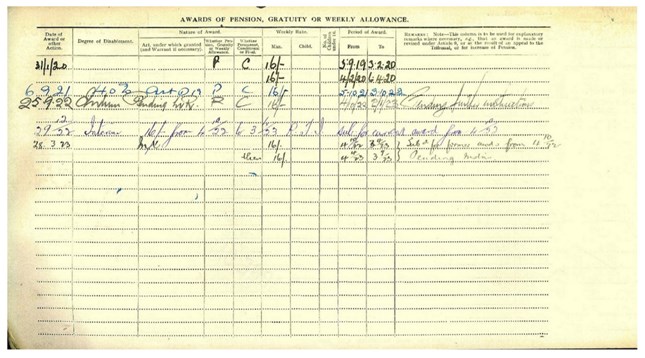

On the ‘AWARDS OF PENSION, GRATUITY OR WEEKLY ALLOWANCE’ page we can see the dates of the first period of the award of the pension – 5(?).9.19 to 3.2.20. This is not consistent with the entry in the first column which reads 31/1/20 although it seems to be written by the same hand.

We can also see that the award was a pension and that it was conditional ie not to be regarded as a permanent award.

The next entry indicates 40% disablement so the award of the pension of 16/- would not have been the maximum.

The award of pension continues on an ‘interim’ basis of 40% disablement, presumably, subject to further medical examinations which seem to have occurred fairly frequently.

The last entry on this page indicates that payment of pension is recommended until 3.9.23 ‘Pending Instns.’

On Form S.B. 36 in the ‘ACTION TAKEN’ section we see two dated entries for 26.8.24 (6.8.24) and underneath 21.8. 24(?). These would seem to indicate some official closure of the pension file.

In the left hand column ‘OTHER ACTION’ there is an interesting entry: ‘Mr O’Brien Payments 22/9/23’. Was Mr O’Brien a physician/surgeon/consultant? Was it he who set the level of pension payments? (Or were the ‘payments’ his fee?)

There are quite a few initial letters and abbreviations which I cannot translate! The red stamp ‘OK’ seems to indicate official recognition of a correct record. Completely baffling is the big green stamp dated 8 May 1935 – CHARGE CARRIED TO DUMMY. This is something that appears on a number these forms. I have no real idea of what it means. It is possible that there was a second pension ledger ie a ‘dummy’ ledger, maybe a kind of ‘fair copy’, abbreviated and ‘neatened up’. But there is no indication of its whereabouts.

It would seem that in 1923 Private Boyle was judged to have been no longer in need of an army pension. We can only guess his feelings about this and he seems not to have received any formal explanation. Presumably, the authorities concluded that he had made an adequate recovery from the wounds he received during the war. It may well have been (and I think it highly likely) that the view was taken that his disability from damage to his mitral valve was no greater than that of a civilian with the same condition (and who would, of course, not have had a pension or allowance of any kind). The decision may have been made by one of the people whose names or initials are displayed on the pension record.

Army disability pensions continued to be paid by the British authorities after the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 so this would not have been a factor in the cessation of Private Boyle’s pension. Soldiers’ pensions were funded from, and administered exclusively by, the British authorities.

The damage to his mitral valve would have been permanent – surgery necessary for its repair was not possible until the late 1940’s, as far as I am aware. It would have made him breathless if he exerted himself to any great extent and would have resulted in discomfort, a build up of fluid in the lungs and possibly angina.

The British authorities were frankly extremely mean with former soldiers’ pensions. Every claimant had to make a case for the award of a pension and maintain that case unless the award from the outset had been made permanent.

Arthur Boyle would have had to attend for medical examination (and this he did on at least five occasions according to this record) in Dublin where the pension records were originally kept (indicated by the number 13, top right hand corner of FORM S.B. 36). Would these journeys have to have been undertaken at his own expense?

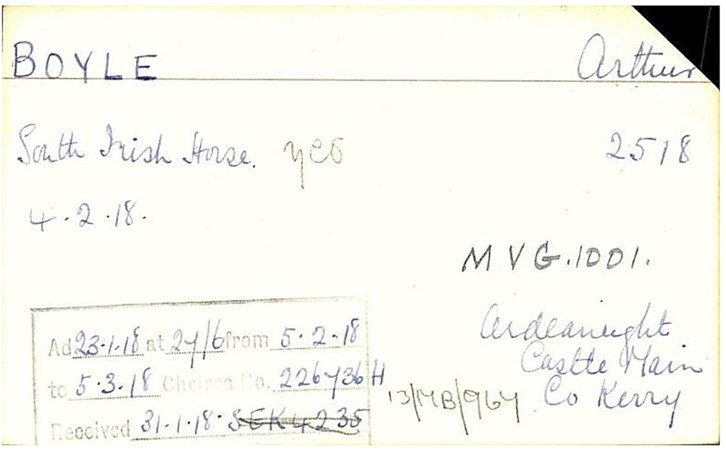

The small Pension Index Record Card (sometimes referred to as the ‘Chelsea Card’) contains some date information which probably has some significance for official record keeping and confirms Private Boyle’s Regiment and Regimental Number. It was probably not written by an Irishman – note the misspelling of the name of his home and the spelling of Castlemaine as Castle Main! It indicates where Private Boyle’s pension would be administered: 13 (Dublin). MB/967 refers to the Medical Board that Private Boyle would have had to attend for examination.

The ‘Chelsea No.’ entry (very faint on a faint scan – 226736H) is interesting. ALL those in receipt of an army pension were regarded officially as ‘Chelsea Pensioners’. Those who lived in the Royal Hospital, Chelsea were known as ‘In Pensioners’*. Those who did not, and lived in their own homes (ie very nearly all of them since only just over 300 are accommodated in the Royal Hospital) were termed ‘Out Pensioners’ in receipt of an ‘Out Pension’. However, since all those who received an army pension were technically Chelsea Pensioners all were therefore given a ‘Chelsea Number’ which was unique and a means of avoiding the occasional confusion between the Army Number and the Regimental Number a soldier was given.

*Chelsea Pensioners are often seen wearing their scarlet coats and black shakos (on official occasions – black tricorne hats) by tourists in London.

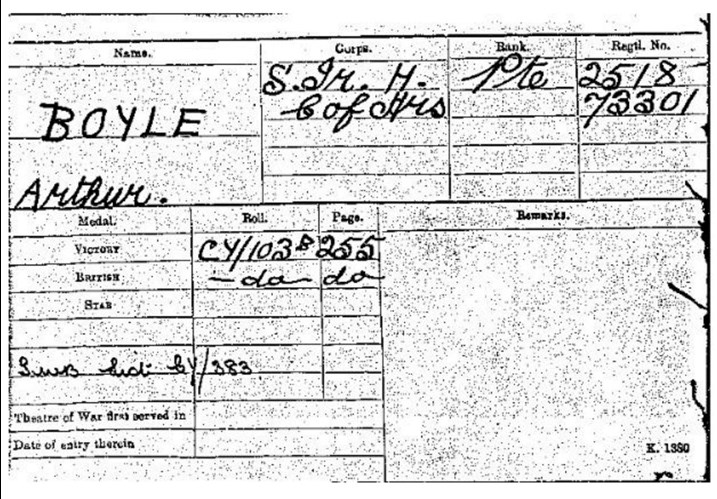

Arthur Boyle’s Medal Record: ‘Victory Medal’, ‘British War Medal’ and ‘Silver War Badge’ (indicating honourable discharge because of wounds received, inscribed: ‘FOR KING AND EMPIRE SERVICES RENDERED’)

The South Irish Horse was part of the Royal Corps of Hussars so Private Boyle had a Corps Service Number in addition to his Regimental Service Number.

My thanks to Arthur Boyle’s grandson who made available his Pension Record and supplied further information.

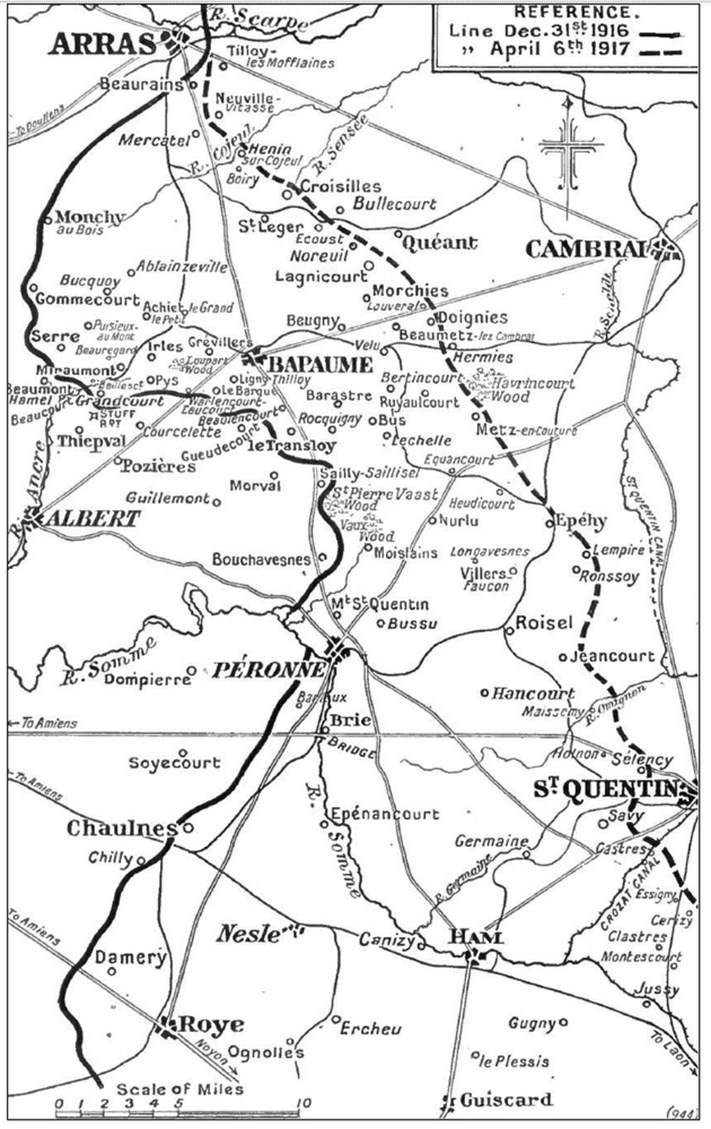

The Hindenburg Line facing the British Sector 1917

Private Arthur Boyle’s Battalion would have been in trenches to the north east of Ronssoy

(half way up on the right hand side of the map).

Map source: ‘The Times’ History of the War 1914-1921’

Peter Crook

August 2018